полная версия

полная версияThe Moral and Intellectual Diversity of Races

I believe that both individual and national character admit of a certain degree of pressure by surrounding circumstances; the pressure removed, the character at once regains its original form. See with what kindliness the civilized descendant of the wild Teuton hunter takes to the hunter's life in new countries, and how soon he learns to despise the comforts of civilized life and fix his abode in the solitary wilderness. The Normans had been settled over six centuries in the beautiful province of France, to which they gave their name; their nobles had frequented the most polished court in Europe, adapted themselves to the fashions and requirements of life in a luxurious metropolis; they themselves had learned to plough the soil instead of the wave; yet in another hemisphere they at once regained their ancient habits, and – as six hundred years before – became the most dreaded pirates of the seas they infested; the savage buccaneers of the Spanish main. I can see no difference between Lolonnois and his followers, and the terrible men of the north (his lineal ancestors) that ravaged the shores of the Seine and the Rhine, and whose name is even yet mentioned with horror every evening, in the other hemisphere, by thousands of praying children: "God preserve us from the Northmen." Morgan, the Welch buccaneer, who, with a thousand men, vanquished five times as many well-equipped Spaniards, took their principal cities, Porto Bello and Panama; who tortured his captives to make them reveal the hiding-place of their treasure; Morgan might have been – sixteen centuries notwithstanding – a tributary chief to Caractacus, or one of those who opposed Cæsar's landing in Britain. To make the resemblance still more complete, the laws and regulations of these lawless bands were a precise copy of those to which their not more savage ancestors bound themselves.

I regret that my limited space precludes me from entering into a more elaborate exposition of the futility of the theory that civilization, or a long continued state of peace, can produce physical degeneracy or inaptitude for the ruder duties of the battle-field; but I believe that what I have said will suffice to suggest to the thoughtful reader numerous confirmations of my position; and I may, therefore, now refer him to Mr. Gobineau's explanation of the term degeneracy. – H.

51

"Nothing but the great number of citizens in a state can occasion the flourishing of the arts and sciences. Accordingly, we see that, in all ages, it was great empires only which enjoyed this advantage. In these great states, the arts, especially that of agriculture, were soon brought to great perfection, and thus that leisure afforded to a considerable number of men, which is so necessary to study and speculation. The Babylonians, Assyrians, and Egyptians, had the advantage of being formed into regular, well-constituted states." —Origin of Laws and Sciences, and their Progress among the most Ancient Nations. By President De Goguet. Edinburgh, 1761, vol. i. pp. 272-273. – H.

52

"Conquests, by uniting many nations under one sovereign, have formed great and powerful empires, out of the ruins of many petty states. In these great empires, men began insensibly to form clearer views of politics, juster and more salutary notions of government. Experience taught them to avoid the errors which had occasioned the ruin of the nations whom they had subdued, and put them upon taking measures to prevent surprises, invasions, and the like misfortunes. With these views they fortified cities, secured such passes as might have admitted an enemy into their country, and kept a certain number of troops constantly on foot. By these precautions, several States rendered themselves formidable to their neighbors, and none durst lightly attack powers which were every way so respectable. The interior parts of such mighty monarchies were no longer exposed to ravages and devastations. War was driven far from the centre, and only infected the frontiers. The inhabitants of the country, and of the cities, began to breathe in safety. The calamities which conquests and revolutions had occasioned, disappeared; but the blessings which had grown out of them, remained. Ingenious and active spirits, encouraged by the repose which they enjoyed, devoted themselves to study. It was in the bosom of great empires the arts were invented, and the sciences had their birth." —Op. cit., vol. i. Book 5, p. 326. – H.

53

The history of every great empire proves the correctness of this remark. The conqueror never attempted to change the manners or local institutions of the peoples subdued, but contented himself with an acknowledgment of his supremacy, the payment of tribute, and the rendering of assistance in war. Those who have pursued a contrary course, may be likened to an overflowing river, which, though it leaves temporary marks of its destructive course behind, must, sooner or later, return to its bed, and, in a short time, its invasions are forgotten, and their traces obliterated. – H.

54

The most striking illustration of the correctness of this reasoning, is found in Roman history, the earlier portion of which is – thanks to Niebuhr's genius – just beginning to be understood. The lawless followers of Romulus first coalesced with the Sabines; the two nations united, then compelled the Albans to raze their city to the ground, and settle in Rome. Next came the Latins, to whom, also, a portion of the city was allotted for settlement. These two conquered nations were, of course, not permitted the same civil and political privileges as the conquerors, and, with the exception of a few noble families among them (which probably had been, from the beginning, in the interests of the conquerors), these tribes formed the plebs. The distinction by nations was forgotten, and had become a distinction of classes. Then began the progress which Mr. Gobineau describes. The Plebeians first gained their tribunes, who could protect their interests against the one-sided legislation of the dominant class; then, the right of discussing and deciding certain public questions in the comitia, or public assembly. Next, the law prohibiting intermarriage between the Patricians and Plebeians was repealed; and thus, in course of time, the government changed from an oligarchical to a democratic form. I might go into details, or, I might mention other nations in which the same process is equally manifest, but I think the above well-known facts sufficient to bring the author's idea into a clear light, and illustrate its correctness. The history of the Middle Ages, the establishment of serfdom and its gradual abolition, also furnish an analogue.

Wherever we see an hereditary aristocracy (whether called class or caste), it will be found to originate in a race, which, if no longer dominant, was once conqueror. Before the Norman conquest, the English aristocracy was Saxon, there were no nobles of the ancient British blood, east of Wales; after the conquest, the aristocracy was Norman, and nine-tenths of the noble families of England to this day trace, or pretend to trace, their origin to that stock. The noble French families, anterior to the Revolution, were almost all of Frankish or Burgundian origin. The same observation applies everywhere else. In support of my opinion, I have Niebuhr's great authority: "Wherever there are castes, they are the consequence of foreign conquest and subjugation; it is impossible for a nation to submit to such a system, unless it be compelled by the calamities of a conquest. By this means only it is, that, contrary to the will of a people, circumstances arise which afterwards assume the character of a division into classes or castes." —Lect. on Anc. Hist. (In the English translation, this passage occurs in vol. i. p. 90.)

In conclusion, I would observe that, whenever it becomes politic to flatter the mass of the people, the fact of conquest is denied. Thus, English writers labored hard to prove that William the Norman did not, in reality, conquer the Saxons. Some time before the French Revolution, the same was attempted to be proved in the case of the Germanic tribes in France. L'Abbé du Bos, and other writers, taxed their ingenuity to disguise an obvious fact, and to hide the truth under a pile of ponderous volumes. – H.

55

"It has been a favorite thesis with many writers, to pretend that the Saxon government was, at the time of the conquest, by no means subverted; that William of Normandy legally acceded to the throne, and, consequently, to the engagements of the Saxon kings… But, if we consider that the manner in which the public power is formed in a state, is so very essential a part of its government, and that a thorough change in this respect was introduced into England by the conquest, we shall not scruple to allow that a new government was established. Nay, as almost the whole landed property in the kingdom was, at that time, transferred to other hands, a new system of criminal justice introduced, and the language of the law moreover altered, the revolution may be said to have been such as is not, perhaps, to be paralleled in the history of any other country." – De Lolme's English Constitution, c. i., note c. – "The battle of Hastings, and the events which followed it, not only placed a Duke of Normandy on the English throne, but gave up the whole population of England to the tyranny of the Norman race. The subjugation of a nation has seldom, even in Asia, been more complete." – Macaulay's History of England, vol. i. p. 10. – H.

56

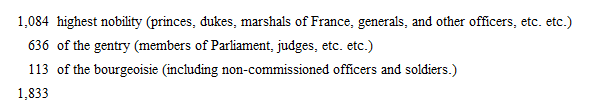

This assertion seems self-evident; it may, however, be not altogether irrelevant to the subject, to direct attention to a few facts in illustration of it. Great national calamities like wars, proscriptions, and revolutions, are like thunderbolts, striking mostly the objects of greatest elevation. We have seen that a conquering race generally, for a long time even after the conquest has been forgotten, forms an aristocracy, which generally monopolizes the prominent positions. In great political convulsions, this aristocracy suffers most, often in numbers, and always in proportion. Thus, at the battle of Cannæ, from 5,000 to 6,000 Roman knights are said to have been slain, and, at all times, the officer's dress has furnished the most conspicuous, and at the same time the most important target for the death-dealing stroke. In those fearful proscriptions, in which Sylla and Marius vied with each other in wholesale slaughter, the number of victims included two hundred senators and thirty-three ex-consuls. That the major part of the rest were prominent men, and therefore patricians, is obvious from the nature of this persecution. Revolutions are most often, though not always, produced by a fermentation among the mass of the population, who have a heavy score to settle against a class that has domineered and tyrannized over them. Their fury, therefore, is directed against this aristocracy. I have now before me a curious document (first published in the Prussian State-Gazette, in 1828, and for which I am indebted to a little German volume, Das Menschengeschlecht auf seinem Gegenwärtigen Standpuncte, by Smidt-Phiseldeck), giving a list of the victims that fell under the guillotine by sentence of the revolutionary tribunal, from August, 1792, to the 27th of July, 1794, in a little less than two years. The number of victims there given is 2,774. Of these, 941 are of rank unknown. The remaining 1,833 may be divided in the following proportions: —

Such facts require no comments. – H.

57

• The recent insurrection in China has given rise to a great deal of speculation, and various are the opinions that have been formed respecting it. But it is now pretty generally conceded that it is a great national movement, and, therefore, must ultimately be successful. The history of this insurrection, by Mr. Callery and Dr. Ivan (one the interpreter, and the other the physician of the French embassy in China, and both well known and reliable authorities) leaves no doubt upon the subject. One of the most significant signs in this movement is the cutting off the tails, and letting the hair grow, which is being practised, says Dr. Ivan, in all the great cities, and in the very teeth of the mandarins. (Ins. in China, p. 243.) Let not the reader smile at this seemingly puerile demonstration, or underrate its importance. Apparently trivial occurrences are often the harbingers of the most important events. Were I to see in the streets of Berlin or Vienna, men with long beards or hats of a certain shape, I should know that serious troubles are to be expected; and in proportion to the number of such men, I should consider the catastrophe more or less near at hand, and the monarch's crown in danger. When the Lombard stops smoking in the streets, he meditates a revolution; and France is comparatively safe, even though every street in Paris is barricaded, and blood flows in torrents; but when bands march through the streets singing the ça ira, we know that to-morrow the Red Republic will be proclaimed. All these are silent, but expressive demonstrations of the prevalence of a certain principle among the masses. Such a one is the cutting off of the tail among the Chinese. Nor is this a mere emblem. The shaved crown and the tail are the brands of conquest, a mark of degradation imposed by the Mantchoos on the subjugated race. The Chinese have never abandoned the hope of one day expelling their conquerors, as they did already once before. "Ever since the fall of the Mings," says Dr. Ivan, "and the accession of the Mantchoo dynasty, clandestine associations – these intellectual laboratories of declining states – have been incessantly in operation. The most celebrated of these secret societies, that of the Triad, or the three principles, commands so extensive and powerful an organization, that its members may be found throughout China, and wherever the Chinese emigrate; so that there is no great exaggeration in the Chinese saying: 'When three of us are together, the Triad is among us.'" (Hist. of the Insur. in Ch., p. 112.) Again, the writer says: "The revolutionary impetus is now so strong, the affairs of the pretender or chief of the insurrection in so prosperous a condition, that the success of his cause has nothing to fear from the loss of a battle. It would require a series of unprecedented reverses to ruin his hopes" (p. 243 and 245).

I have written this somewhat lengthy note to show that Mr. Gobineau makes no rash assertion, when he says that the Mantchoos are about to experience the same fate as their Tartar predecessors. – H.

58

The author might have mentioned Russia in illustration of his position. The star of no nation that we are acquainted with has suffered an eclipse so total and so protracted, nor re-appeared with so much brilliancy. Russia, whose history so many believe to date from the time of Peter the Great only, was one of the earliest actors on the stage of modern history. Its people had adopted Christianity when our forefathers were yet heathens; its princes formed matrimonial alliances with the monarchs of Byzantine Rome, while Charlemagne was driving the reluctant Saxon barbarians by thousands into rivers to be baptized en masse. Russia had magnificent cities before Paris was more than a collection of hovels on a small island of the Seine. Its monarchs actually contemplated, and not without well-founded hopes, the conquest of Constantinople, while the Norman barges were devastating the coasts and river-shores of Western Europe. Nay, to that far-off, almost polar region, the enterprise of the inhabitants had attracted the genius of commerce and its attendants, prosperity and abundance. One of the greatest commercial cities of the first centuries after Christ, one of the first of the Hanse-Towns, was the great city of Novogorod, the capital of a republic that furnished three hundred thousand fighting men. But the east of Europe was not destined to outstrip the west in the great race of progress. The millions of Tartars, that, locust-like – but more formidable – marked their progress by hopeless devastation, had converted the greater portion of Asia into a desert, and now sought a new field for their savage exploits. Russia stood the first brunt, and its conquest exhausted the strength of the ruthless foe, and saved Western Europe from overwhelming ruin. In the beginning of the thirteenth century, five hundred thousand Tartar horsemen crossed the Ural Mountains. Slow, but gradual, was their progress. The Russian armies were trampled down by this countless cavalry. But the resistance must have been a brave and vigorous one, for few of the invaders lived long enough to see the conquest. Not until after a desperate struggle of fifty years, did Russia acknowledge a Tartar master. Nor were the conquerors even then allowed to enjoy their prize in peace. For two centuries more, the Russians never remitted their efforts to regain their independence. Each generation transmitted to its posterity the remembrance of that precious treasure, and the care of reconquering it. Nor were their efforts unsuccessful. Year after year the Tartars saw the prize gliding from their grasp, and towards the end of the fifteenth century, we find them driven to the banks of the Volga, and the coasts of the Black Sea. Russia now began to breathe again. But, lo! during the long struggle, Pole and Swede had vied with the Tartar in stripping her of her fairest domains. Her territory extended scarce two hundred miles, in any direction from Moscow. Her very name was unknown. Western Europe had forgotten her. The same causes that established the feudal system there, had, in the course of two centuries and a half, changed a nation of freemen into a nation of serfs. The arts of peace were lost, the military element had gained an undue preponderance, and a band of soldiers, like the Pretorian Guards of Rome, made and deposed sovereigns, and shook the state to its very foundations. Yet here and there a vigorous monarch appeared, who controlled the fierce element, and directed it to the weal of the state. Smolensk, the fairest portion of the ancient Russian domain, was re-conquered from the Pole. The Swede, also, was forced to disgorge a portion of his spoils. But it was reserved for Peter the Great and his successors to restore to Russia the rank she had once held, and to which she was entitled.

I will not further trespass on the patience of the reader, now that we have arrived at that portion of Russian history which many think the first. I would merely observe that not only did Peter add to his empire no territory that had not formerly belonged to it, but even Catharine, at the first partition of Poland (I speak not of the subsequent ones), merely re-united to her dominion what once were integral portions. The rapid growth of Russia, since she has reassumed her station among the nations of the earth, is well known. Cities have sprung up in places where once the nomad had pitched his tent. A great capital, the handsomest in the world, has risen from the marsh, within one hundred and fifty years after the founder, whose name it perpetuates, had laid the first stone. Another has risen from the ashes, within less than a decade of years from the time when – a holocaust on the altar of patriotism – its flames announced to the world the vengeance of a nation on an intemperate aggressor.

Truly, it seems to me, that Mr. Gobineau could not have chosen a better illustration of his position, that the mere accident of conquest can not annihilate a nation, than this great empire, in whose history conquest forms so terrible and so long an episode, that the portion anterior to it is almost forgotten to this day. – H.

59

The author of Democracy in America (vol. ii. book 3, ch. 1), speculating upon the total want of sympathy among the various classes of an aristocratic community, says: "Each caste has its own opinions, feelings, rights, manners, and mode of living. The members of each caste do not resemble the rest of their fellow-citizens; they do not think and feel in the same manner, and believe themselves a distinct race… When the chroniclers of the Middle Ages, who all belonged to the aristocracy by birth and education, relate the tragical end of a noble, their grief flows apace; while they tell, with the utmost indifference, of massacres and tortures inflicted on the common people. In this they were actuated by an instinct rather than by a passion, for they felt no habitual hatred or systematic disdain for the people: war between the several classes of the community was not yet declared." The writer gives extracts from Mme. de Sevigné's letters, displaying, to use his own words, "a cruel jocularity which, in our day, the harshest man writing to the most insensible person of his acquaintance would not venture to indulge in; and yet Madame de Sevigné was not selfish or cruel; she was passionately attached to her children, and ever ready to sympathize with her friends, and she treated her servants and vassals with kindness and indulgence." "Whence does this arise?" asks M. De Tocqueville; "have we really more sensibility than our forefathers?" When it is recollected, as has been pointed out in a previous note, that the nobility of France were of Germanic, and the peasantry of Celtic origin, we will find in this an additional proof of the correctness of our author's theory. Thanks to the revolution, the barriers that separated the various ranks have been torn down, and continual intermixture has blended the blood of the Frankish noble and of the Gallic boor. Wherever this fusion has not yet taken place, or but imperfectly, M. De Tocqueville's remarks still apply. – H.

60

The spirit of clanship is so strong in the Arab tribes, and their instinct of ethnical isolation so powerful, that it often displays itself in a rather odd manner. A traveller (Mr. Fulgence Fresnel, if I am not mistaken) relates that at Djidda, where morality is at a rather low ebb, the same Bedouine who cannot resist the slightest pecuniary temptation, would think herself forever dishonored, if she were joined in lawful wedlock to the Turk or European, to whose embrace she willingly yields while she despises him.

61

The manOf virtuous soul commands not, nor obeys.Power, like a desolating pestilence,Pollutes whate'er it touches; and obedience,Bane of all genius, virtue, freedom, truth,Makes slaves of man, and of the human frameA mechanized automaton.Shelley, Queen Mab.[63]62

Montesquieu expresses a similar idea, in his usual epigrammatic style. "The customs of an enslaved people," says he, "are a part of their servitude; those of a free people, a part of their liberty." —Esprit des Lois, b. xix. c. 27. – H.

63

"A great portion of the peculiarities of the Spartan constitution and their institutions was assuredly of ancient Doric origin, and must have been rather given up by the other Dorians, than newly invented and instituted by the Spartans." —Niebuhr's Ancient History, vol. i. p. 306. – H.

64

See note on page 121.

65

The amalgamation of races in South America must indeed be inconceivable. "I find," says Alex. von Humboldt, in 1826, "by several statements, that if we estimate the population of the whole of the Spanish colonies at fourteen or fifteen millions of souls, there are, in that number, at most, three millions of pure whites, including about 200,000 Europeans." (Pers. Nar., vol. i. p. 400.) Of the progress which this mongrel population have made in civilization, I cannot give a better idea than by an extract from Dr. Tschudi's work, describing the mode of ploughing in some parts of Chili. "If a field is to be tilled, it is done by two natives, who are furnished with long poles, pointed at one end. The one thrusts his pole, pretty deeply, and in an oblique direction, into the earth, so that it forms an angle with the surface of the ground. The other Indian sticks his pole in, at a little distance, and also obliquely, and he forces it beneath that of his fellow-laborer, so that the first pole lies, as it were, upon the second. The first Indian then presses on his pole, and makes it work on the other, as a lever on its fulcrum, and the earth is thrown up by the point of the pole. Thus they gradually advance, until the whole field is furrowed by this laborious process." (Dr. Tschudi, Travels in Peru, during the years 1838-1842. London, 1847, p. 14.) I really do not think that a counterpart to this could be found, except, perhaps, in the manner of working the mines all over South America. Both Darwin and Tschudi speak of it with surprise. Every pound of ore is brought out of the shafts on men's shoulders. The mines are drained of the water accumulating in them, in the same manner, by means of water-tight bags. Dr. Tschudi describes the process employed for the amalgamation of the quicksilver with the silver ore. It is done by causing them to be trodden together by horses', or human feet. Not only is this method attended with incredible waste of material, and therefore very expensive, but it soon kills the horses employed in it, while the men contract the most fearful, and, generally, incurable diseases! (Op. cit., p. 331-334.) – H.