полная версия

полная версияПозитивные изменения. Том 1, №1 (2021). Positive changes. Volume 1, Issue 1 (2021)

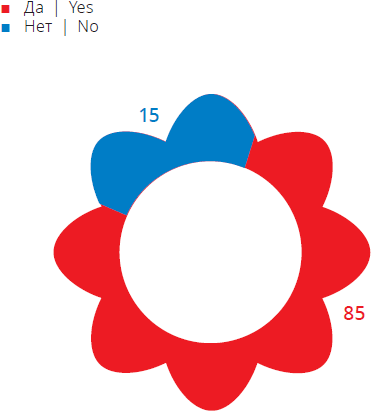

Диаграмма 1. Готовность поменять привычную марку на продукцию социальных предпринимателей, %

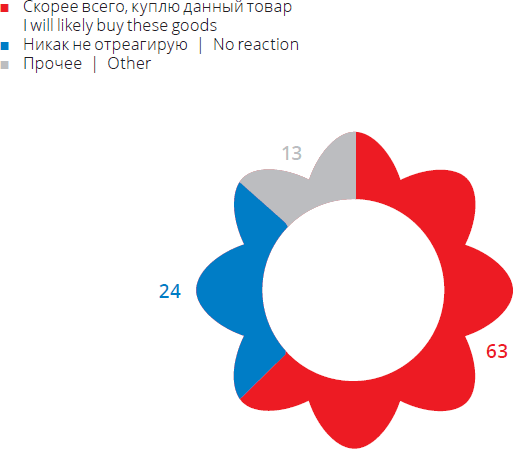

Если вы узнаете, что товар или услуга произведены социально незащищенной группой населения (инвалиды, многодетные семьи и т. п.), как это повлияет на ваш выбор продукции?

Диаграмма 2. Влияние фактора «социального» товара на принятие потребительского решения, %

Попробуем разобраться в причинах, почему все-таки выбор «социального» товара является привлекательным для потребителя с точки зрения психологической теории решения.

Начнем с того, что сама ситуация выбора является внутренне, субъективно задачей отнюдь не всегда приятной. «Бремя выбора» говорим мы в ситуации, когда нужно принять важное решение. Даже выбор, который нам приятен (например, нового платья), рождает напряженность (вдруг куплю не самое лучшее и потом найду дешевле или лучше?), и уж тем более – выбор новой квартиры, профессии и спутника жизни. Все эти ситуации требуют затраты наших психических ресурсов и, кроме того, всегда сопровождаются боязнью совершения неправильного выбора.

К счастью, психика человека обладает большим ресурсом защиты, и одним из принципов ее функционирования является «экономия психической энергии». В каждый момент времени на человека действует множество разнообразных стимулов, часть которых мы даже не осознаем (например, одежду, которая на нас надета, шум кондиционера или улицы за окном – стимулы, которые мы не будем осознавать до тех пор, пока они по каким-то причинам не окажутся в области нашего произвольного или непроизвольного внимания (вследствие, например, внезапного громкого звука за окном). Одним из проявлений данного принципа экономии является и ряд феноменов на уровне принятия решения. Так, для снижения «субъективного дискомфорта», возникающего в ситуации необходимости совершения выбора из нескольких альтернатив, мы используем принцип иерархизации альтернатив, позволяющий выделить обобщенные кластеры вариантов выбора, причем, чем больше множество альтернатив, тем более важную роль играет данный принцип. Или другой принцип – эвристика «редукции сложности» альтернатив: субъект совершает выбор на основании гораздо меньшего количества альтернатив, чем те, которые он может различить. Действительно, если представить количество вариантов выбора, которые мы можем совершить (к примеру, потенциальных спутников жизни – порядка нескольких миллионов, если исходить из критерия пола, возраста и семейного положения; страшно представить, если бы мы захотели осуществить выбор на основании знакомства со всеми вариантами…), становится очевидным, что выбор мы совершаем на основании далеко не всех возможных вариантов. Более того, в своих исследованиях Ю. Козелецкий доказал, что лица, находящиеся в ситуации принятия решения, при совершении выбора принимают во внимание одновременно всего от 3 до 6 гипотез, которые кажутся им наиболее правдоподобными, и игнорируют другие. Почти магические «7±2» – формула, которая описывает многие психологические явления (объем нашей оперативной памяти, внимания например). Такие же данные были получены и в исследованиях других ученых.

Что же все-таки с покупкой социальных товаров? Можно заметить, что в ситуации принятия потребительского решения имеются все условия для возникновения указанных феноменов, позволяющих упростить задачу принятия решения для субъекта. Поиск подходящего варианта выбора в зависимости от типа товарной категории в большей или меньшей степени рождает у потребителя напряженность. В условиях развитости рынка количество потребительских альтернатив может достигать сотен и даже тысяч, что делает невозможным решение задачи выбора анализом каждой отдельной альтернативы и вынуждает субъекта прибегнуть к использованию простых эвристических правил. На основании функционирования этих эвристик наличие «социальной маркировки» становится одним из факторов, облегчающих процесс выбора. В многообразии возможных потребительских альтернатив это способствует снятию субъективного дискомфорта, выделяя из этого многообразия один или ограниченное количество вариантов. «Социальная» альтернатива выбора приобретает особые характеристики, становясь частью психологической ситуации субъекта, если говорить научным языком.

Наличие «социальной маркировки» становится одним из факторов, облегчающих процесс выбора. В многообразии возможных потребительских альтернатив это способствует снятию субъективного дискомфорта.

Постараемся конкретизировать основные эвристики, которые потенциально оказывают влияние на поведение потребителя в случае выбора социального товара. Итак, первая эвристика: мы упрощаем для потребителя задачу выбора, предлагая в качестве критерия «добавленную социальную ценность», «два в одном» – о чем мы писали в начале. Если выбранный «социальный» товар нам понравится, есть все условия для формирования лояльности к этому бренду и превращения покупки в привычную (осуществляемую регулярно в случае необходимости покупки данной категории товаров).

Другой эвристикой является эвристика знакомости, которая выступает основным механизмом влияния рекламы на потребительский выбор. Если все продукты из определенного ассортимента обладают одинаковыми свойствами, то шансов на выбор больше у того продукта, который более знаком потребителю. Она выражается в формуле: «Если из двух похожих товаров об одном ты что-то слышал, а о другом – ничего и никогда, выбирай тот, который тебе знаком». В контексте социального товара действие данной эвристики возможно в случае, когда, например, потребитель знаком с категорией «социального предпринимательства» и видит продукцию, которая сделана социальным предпринимателем. Или, например, слышал о торговом доме «Больше, чем покупка» и видит товар с этой маркировкой. Пока сложно говорить о массовой известности категории социального предпринимательства, но в будущем она может также стать важным фактором выбора.

Еще одной эвристикой, детерминирующей процесс потребительского решения и интересной в контексте «социального», является «зависимость от происхождения». Суть этого феномена состоит в том, что для потребителя имеет значение источник получения ресурсов и «статья расходов», на которую он их тратит. Если потребитель задумывается над тем, что уже потратил определенную сумму по одной статье расходов, то сумма, которую он еще готов потратить по этой же статье расходов в пределах определенного периода времени, становится значительно меньше. Примером проявления этой эвристики является большая вероятность приобретения товара другой категории по сравнению с категорией недавно приобретенного товара. В ситуации «социального» товара возникают условия для возникновения данной эвристики. Допустим, потребитель уже покупал на ярмарке пряники (к слову, пряники были популярным товаром на ярмарках в Городце и Кунгуре, где в 2017 году прошли «Слеты социальных предпринимателей»). Если он увидит на этой же ярмарке не просто пряники, а «пряники, сделанные социальным предпринимателем», то вероятность того, что он их купит, будет выше. В этом случае субъективно меняется «статья расходов»: не пряники купил, а «доброе дело сделал».

Другой эвристикой является «страховка от неправильного выбора», что также снижает дискомфорт и сложность выбора: «Даже если товар окажется плохим (невкусным, быстро сломается), все равно покупкой доброе дело сделал, а потому будет не так грустно от потери денег».

Казалось бы, найден «священный Грааль» продаж. Делайте свой товар «социальным» (хотя бы на уровне «маркировки») – и любовь потребителя вам обеспечена. Однако, нет. Качество продукта и его цена даже в случае «социального» товара являются критическими факторами в принятии потребительского решения (если мы не говорим о благотворительности, с которой мы начали это обсуждение). Кроме того, существуют различные стратегии продвижения социальных товаров, в которых определяется баланс «маркетингового» и «благотворительного». И это другая важная тема, которую мы постараемся рассмотреть в последующих публикациях.

Why People Buy Social Things? Psychology of Consumer Choice

Natalia Gladkikh, Vladimir Vainer

The answer to the question "Why people buy social things?" in first approximation can seem obvious: a desire to help others (based on inner ambitions or "social desirability" of such behavior pattern) is inherent to human nature. But we could limit ourselves with this answer if we were interested only in a situation when a person makes a purchase not because he needs these goods (and as it often happens – he or she doesn't need it at all), but to help a particular orphanage, child, a friend, a charitable foundation, etc.

Natalia Gladkikh,

Ph.D. in Psychology, Leading Expert of the Institute of Socio-Economic Design, Higher School of Economics

Vladimir Vainer,

Director of Positive Changes Factory

Some time ago, a message actively circulated social media calling to buy things from elderly women standing and selling goods near metro stations – not because their goods are of good quality, but because those elderly women are different by the fact of their particular need to earn some money, even small sums. "It seems we all need a geranium plant" that message ended. In this case, we can hardly speak about consumer behavior, but likely about compassionate plea. A model of buying an assumed «geranium» because it is sold by an elderly woman obviously cannot become a regular model – we will have to do something with this geranium. Such charity model – donations in exchange of conventional «goods» – was popular in Russia before the revolution. Charity tokens, White Flowers, Buy a Red Egg and other campaigns that were popular at that time are good examples of such (and we must say – effective) strategy of fundraising. They are popular nowadays. Famous Currant Party of the Creation foundation, "Candid Fair" and many other programmes, offers and campaigns can serve as an example of fundraising based on the «double» profit – I get both goods (and it is not a geranium plant in most cases, but really descent, useful and pleasant product or service) and feeling that I have done something useful.

It is more difficult in the situation when «social» goods enter a competition with «regular» goods on a shop shelve, in a fair row and in other situations of making everyday purchasings. When we talk about a regular consumer behavior with the consumer decision as the key strategy, choice in favour of a certain «alternative» which is defined by target setting, choice criteria and strategies and a plenty of more complex phenomena.

The consumer behavior is a subject of study of many sciences, but in general we can distinguish two large groups – theories not related to psychology, which include economical and mathematical models, with building game theories, statistical decisions, calculations of win-win strategies, etc., and psychology theories described by accounting of the factor of human mentality which «distorts» ideal mathematical and statistical strategies, which occur in everyday human decisions, in real life. We often choose a shop which is not close to us and cheaper, but a shop which is far from us and expensive – just because of a shop assistant who is our friend and we know him for many years. And it is difficult to calculate mathematically a choice of our life partner, for example – we can hardly rely on credits of a conditional test. "A person is not irrational so much so that to always act rationally" – with these words Gregor Simon described the formula of distortions of human mind, he is one of the authors and founders of the psychological approach in studying the process of choosing, and a Nobel Prize winner in economics, by the way. Interestingly enough, that another well-known author of the psychological approach in analyses of the process of choosing – Daniel Kahneman – is also a Nobel Prize winner and also in economics. It turns out that even a strict and rational economy has a space for irrationality of impact of psychological processes in the situation of making a choice.

Works of Kahneman, Simon and many other researchers of the psychological approach are joined by a pursuit to find out how a choice is made in reality. The «heuristic» notion is the important category in this approach. These are simple principles, established algorithms expressed in the form of judgements, which people use to facilitate a task of decision making. Proverbs can serve as examples of heuristics. "For one that is missing there is no spoiling a wedding", "where there’s smoke there’s fire" and other proverbs actually define our behavior in certain situations, help us to make decisions – to wait or to leave, believe or not, etc. We reference to them as a principle of choosing a behavior model in certain situations.

Before we proceed to the analysis of heuristics which define a choice of social goods, first of all we should provide proofs in favour of the judgement in the title as proved one – people buy social things. Do they really buy? Do the goods of social value are "modal alternatives", i.e. a choice option which has advantages compared to others?

Hereinafter I will refer to data of the research we conducted several years ago by the order of Our Future Foundation for regional and social programmes. As Diagrams 1 and 2 show, the respondents are ready to change even the brand they prefer to buy «regularly» (this particular situation – regular purchasing is the most difficult to be changed) for the products of social entrepreneurs. Although, if we review the social desirability of this answer as a correction factor (though, in our case – anonimous online survey – the conditions minimally contributed to its occurrence), we get fairly significant ratio. Partially, the factor of "external validity", i.e. that confirms accuracy of our hypothesis, is active usage of «social» as the strategy of promotion of «regular» goods. The social marketing today represents a well-established and actively developing line of marketing, and at advertising festivals now it is difficult to distinguish the commercial advertising from the social one – humanistic values become the dominant and actively operated values both by charitable Foundations and large corporations (and it is perfect, particularly in case when these campaigns have a great effect not only commercial, but also a social one).

Are you ready to change the brand you regularly buy for the products of social entrepreneurs (made by socially vulnerable groups of citizens) with similar properties in terms of quality, etc.?

Diagram 1. Readiness to change a traditional brand for the products of social entrepreneurs, %

If you find out that goods or service are made by a socially vulnerable group of citizens (physically impaired persons, large families, etc.), how will it impact your choice of products?

Diagram 2. Impact of the factor of «social» goods on making a consumer decision, %

We will try to figure out reasons, why a choice of «social» goods is yet attractive for a consumer, from the point of view of the psychological theory of decisions.

Let’s start from the point that the situation of choice itself intrinsically and subjectively is a task that is not always a pleasant one. We say "burden of choice" in a situation when we have to make an important decision. Although, a pleasant for us choice – a choice of a new dress, for instance – induces tension (what if the dress I buy not the best one and later I will find a cheaper and better one?), let alone a choice of a new flat, profession, and on top of that, a life partner. All these situations require costs of our mental resources and besides go along with a fear to make a wrong choice.

Fortunately, the human mind has a great resource of defense and one of the principle of its functioning is "saving mental energy". At every particular moment, a person is exposed to a wide variety of stimulus, a part of which we even do not aware of (e.g. clothes we are in, noise of the air conditioner or outside the window – stimulus that we will not aware of until they, for one reason or another, turn out to be in the field of our voluntary or involuntary (e.g. as a result of loud sound outside the window). One of the manifestations of this saving principle besides is a series of phenomena at the level of decision making. Thus, to reduce a "subjective discomfort" that arises in a situation when we need to make a choice from several alternatives, we use a principle of the alternative ranking, which allows us to distinguish generalized clusters of choice options, while the larger the alternative set is, the more important role this principle plays. Or another principle – heuristics of "complexity reduction" of alternatives: a subject makes a choice on the basis of considerably less number of alternatives, than those he or she can distinguish. Indeed, if we imagine a number of choice options we can make (e.g. there are as many as several millions of potential life partners, if we assume gender, age and marital status; it is hard to imagine if we wanted to make a choice on the basis of meeting all the potential partners…), it becomes obvious that we make a choice on the basis of far from all possible options. Moreover, Yu. Kozeletsky in his studies proved that people in the situation of decision making take into account 3 to 6 hypotheses at the same time when making a choice, and they assume these hypotheses as mostly credible and ignore the others. Almost magical "7+/-2" – the formula that describes many psychological phenomena (e.g. capacity of our recent memory, attention). The same data were obtained in studies of other scientists.

Nevertheless, what’s with purchasing of social goods? One can note, that for the situation of making a consumer decision all conditions for occurrence of the described phenomena are available, and they allow to facilitate the task of decision making for a subject. Searching for a suitable choice option depending on a type of goods category induces tension to a greater or lesser degree. In conditions of the developed market, the amount of consumer alternatives can achieve hundreds or even thousands, which makes it impossible to resolve the task of choice by analysing every particular alternative, thus it impels the subject to opt for simple heuristic rules. On the basis of these functioning heuristics, the availability of the "social brand" becomes one of the factors that facilitate choosing. In the variety of possible consumer alternatives, this encourages a relief from subjective discomfort, distinguishing one or limited number of options from this variety. The «social» alternative of choice gains specific features, while becoming a psychological language – a part of psychological situation of a subject.

We will endeavor to pinpoint the basic heuristics which potentially influence the consumer behavior in case of choosing social goods. So, the first heuristic – we simplify a task of choice for the consumer by suggesting an "added social value" as a criterion, «two-in-one» – as we described in the beginning. If in this case we like chosen «social» goods, there are all conditions for generation of loyalty to this brand and this purchase can become a regular purchase (made on a regular basis, in case of necessity of buying this category of goods).

Another heuristic is the «familiarity», which is the primary mechanism of influencing the consumer choice by the advertising. In case when all the products in a certain range have similar properties, the chances of choosing the products more familiar to the consumer are greater. It is reflected by the following principle: "If of two similar goods you have heard something about one and nothing about the other, choose the one you know". This heuristic is possible in the scope of social goods, i.e., when the consumer is familiar with the category of "social entrepreneurship" and sees the goods produced by a social entrepreneur. Or, for example, the consumer has heard about the trading company "More than buying" and sees the goods with this label. So far it is too soon to speak of the massive popularity of the social entrepreneurship, but in the future it may also become an important choice factor.

"Origin dependency" is another heuristic determining the consumer choice process which is interesting in the context of the «social» aspect. The point of this phenomenon is that what matters to the consumer is the source of resources and the "item of expenditure" on which he spends them. If a consumer thinks about the fact that he or she has already spent a certain amount on one expense item, the amount he or she is still willing to spend on the same expense item within a certain period of time becomes significantly less. The greater likelihood of purchasing goods in a different category than in the category of recently purchased goods is an example of this heuristic demonstration. The conditions for the development of such heuristic arise in case of the «social» goods. For example, if the consumer has already bought (for instance, at the fair) some goods (for example, gingerbread – popular goods at fairs in Gorodets or Kungur, where in 2017 there were "Rallies of social entrepreneurs"), then the probability that again having met at the same fair not just gingerbread, but "gingerbread made by social entrepreneur", he will also buy them, will increase. In this case, subjectively, the "item of expenditure" changes – not the gingerbread, but the "good deed".

The availability of the "social brand" becomes one of the factors that facilitate choosing. In the variety of possible consumer alternatives, this encourages a relief from subjective discomfort.

Another heuristic is "insurance against a wrong choice," which also reduces the discomfort and difficulty of choice: "Even if it turns out to be bad (bad taste, will break quickly, etc.) – I still did good thing," which means "there is no need to regret the buy".

Supposedly, the "holy grail" of sales has been found. Just make your goods «social» (even the level of «label» will be enough) – and the love of the consumers is assured. But in fact, this is not true. Goods quality and its price, even in case of «social» goods have critical factors of the consumer choice (if we are not talking about "charity," which was mentioned above). Moreover, there are various strategies for promoting social goods, establishing the balance of «marketing» and «charity». And this is another important issue that we will try to address in our future publications.

Когда слово равно делу. Социальное воздействие посредством медиа и способы его измерения

Юлия Агеева

Среди тех, кто занимается реализацией проектов социальных изменений, будь то бизнес, некоммерческие организации (НКО) и даже государство, сложно найти тех, кто рассматривал бы присутствие своих проектов в медиа как значимый элемент социального воздействия. Встретить в описании целей проекта изменение установок людей посредством медиа, их поведенческих моделей в отношении решаемой проектом социальной проблемы можно разве что в ситуации, когда содержание проекта состоит в реализации информационной кампании.

Юлия Агеева,

SMM-специалист

Между тем иногда именно сказанная в интервью фраза или случай из практики может стать тем самым «пусковым механизмом», который вдохновит зрителя или читателя по-дружески, а не со страхом отнестись к людям с особенностями развития, сподвигнет на финансовую помощь фондам или волонтерскую деятельность. Почему так мало внимания уделяется медиаприсутствию при реализации проекта и что можно было бы сделать, чтобы изменить ситуацию?