полная версия

полная версияThe Fiction Factory

There was once a magazine that bore as its title the name of a publisher as famous as any American ever saw, and the editor bought a story of me at the rate of half a cent a word, and owed me two years for it. Finally, one time when I was very hard up I went to the office and hung around until I could see the 'boss' and put it up to him to pay me. He did. He knocked off 33 1-3 per cent for 'cash.' Pretty good, eh?

I tell you, Edwards, there's nothing funny in the game that I can see – not for the so-called literary worker. The gods may laugh when they see a man with that brand of insanity on him that actually forces him to write. But I doubt if the writer laughs – not even if he writes a 'best seller.' For success entails turning out other successes, and that is hard work. Excuse me! I am going back to the farm. I will write only when I have to, and only as long as my farm will not support me. I've got hold of a pretty good place cheap, down here with the outlook of making a good living on it in time. No more the Great White Way, with the Dirty Black Alley behind it, in mine! I am not going to carry my hat in my hand around to editors' offices and take up collections for long. Besides, most of the editors blooming now are just out of college and are not dry behind the ears yet. They think that Johnny Go-bang, who edited the sporting page in the Podunk University Screamer, knows more about writing fiction than the old fellows who have been at it a couple of decades. And I reckon they are right. They are looking for 'fresh' material; some of it is pretty 'raw' as well as fresh. I fooled an editor the other day by sending a manuscript on strange paper, written on a new typewriter, and with an assumed name attached. Sold the story and got a long letter of encouragement from the editor. Great game – encouraging 'new' writers! About on a par with the scheme some rum sellers have of washing their sidewalks with the dregs of beer kegs. The spider and fly game. Now, if I told that editor what an ass he had made of himself, would he ever buy another manuscript of me again? I fear not!

Perhaps I am pessimistic, Brother Edwards. There's no real fun in the writing game – not for the writer, at least. Not when he is forty years old and knows that already he is a 'has-been.' Good luck to you. Hope your book is a success, and if I really knew just what you wanted I'd try to whip something into shape for you. For you very well know that, if other fiction writers give you incidents for your book, they'll mostly be fiction! That is the devil of it. If a fiction writer cuts a sliver off his thumb while paring the corned beef for dinner, he will make out of the story a gory combat between his hero and a horde of enemies, and give details of the carnage fit to make his own soul shudder.

I hope to meet up with you again some time. But pretty soon when I go to New York I'll wear my chin-whiskers long and carry a carpet-bag; and you bet I'll fight shy of editors' offices."

Another example of injustice to writers which, however, happened to turn out well for the writer:

"I offered a short serial to a certain newspaper syndicate. Soon I received a letter saying they could pay me $200 for the serial rights. Before my letter accepting the offer reached them, I had another letter from the syndicate withdrawing the offer. The editor stated pathetically that the proprietor had returned and had asked him to withdraw it. I then sent the serial to a Chicago newspaper, which paid me $200 for serial rights – BUT NEVER PUBLISHED THE STORY. Finally I rewrote the story, had it published as a book by a leading Eastern publishing house, and it sold well."

Here, again, is injustice of another kind:

"Once a certain Eastern magazine authorized me to go to Santa Fe, New Mexico, and write a description of a Pueblo dance and of Pueblo life, and send the manuscript on with photographs for illustration. I did the work. And I was rewarded by the generous editor with a check for $20! You can imagine how profitable that particular stunt was, for I took a week's time and paid my own expenses. But not out of that twenty. There wasn't enough of it to go 'round."

XXIV

WHAT SHALL

WE DO

WITH IT?

Edwards wrote only one serial story during 1910, and turned his hand to that merely to bring up the financial returns and leave a safe margin for expenses. Nickel novels, a few short stories, a novelette for The Blue Book and the lengthening of two stories for paper-book publication comprised the year's work. He "soldiered" a little, but when a writer "soldiers" he is not necessarily idle. Edwards' thoughts were busy, and the burden of his reflections was this: Heaven had endowed him with a small gift of plot and counter-plot, and a little art for getting it into commercial form; but were his meager talents producing for him all that they should? Was the purely commercial aim, although held to with a strong sense of moral responsibility, the correct aim? After a score of years of hard work did he find himself progressing in any but a financial direction? Forgetting the past and facing the future with eyes fixed at a higher angle, how was he to proceed with his "little gift of words?" What should he do with it?

In the bright summer afternoons Edwards would walk out of his Fiction Factory and make a survey of it from various points. He was always so close to his work that he lost the true perspective. He was familiar with the minutiae, the thousand and one little details that went to make up the whole, but how did it look in the "all-together," stripped of sentiment and beheld in its three dimensions?

Paradoxically, the work appeared too commercial in some of its aspects, and not commercial enough in others. The sordid values were due to the demand which came to Edwards constantly and unsolicited, and which it was his unvarying policy always to meet. "All's fish that comes to the writer's net" was a saying of Edwards' that had cozzened his judgment. He was giving his best to work whose very nature kept him to a dead level of mediocrity. And within the last few years he had become unpleasantly aware that at least one editor believed him incapable of better things. This was largely Edwards' fault. Orders for material along the same old lines poured in upon him and he hesitated to break away from them and try out his literary wings.

Years before he had faced a similar question. The same principal of breaking away from something that was reasonably sure and regular for something else not so sure but which glowed with brighter possibilities, was involved. Vaguely he felt the call. He was forty-four, and had left behind him twenty-odd years of hard and conscientious effort. As he was getting on in years so should he be getting on with some of his dreams, before the light failed and the Fiction Factory grew dark and all dreaming and doing were at an end.

One evening in Christmas week, 1910, he mentioned his aspirations to a noted editor with whom he happened to be at dinner. The book that was to bring fame and fortune, the book Edwards had always been going to write but had never been able to find the time, was under discussion. "Write it," advised the noted one, "but not under your own name."

Edwards fell silent. What was there in the work he had done which made it impossible to put "John Milton Edwards" on the title page of his most ambitious effort? Were the nickel novels and the popular paper-backs to rise in judgment against him? He could not think so then, and he does not think so now.

"Why don't you write up your experiences as an author?" inquired the editor a few moments later. "You want to be helpful, eh? Well, there's your chance. Writers would not be the only ones to welcome such a book, and if you did it fairly well it ought to make a hit."

This suggestion Edwards adopted. Having the courage of convictions directly opposed to the noted editor's, the other one he will not accept.

The reflections of 1910 began to bear fruit in 1911. With the beginning of the present year Edwards gave up the five-cent fiction, not because – as already stated in a previous chapter – he considered it debasing to his "art," but because he needed time for the working out of a few of his dreams.

Presently, as though to confirm him in his determination, two publishing houses of high standing requested novels to be issued with their imprint. He accepted both commissions, and at this writing the work is well advanced. If he fails of material success in either or both these undertakings, by the standards elsewhere quoted and in which he thoroughly believes, the higher success that cannot be separated from faithful effort will yet be his. And it will suffice.

Even in 1910 Edwards had been swayed by his growing convictions. Almost unconsciously he had begun shaping his work along the line of higher achievement. During 1911 he has been hewing to the same line, but more consistently.

Edwards has demonstrated his ability to write moving picture scenarios that will sell. But is the game worth the candle? Is it pleasant for an author to see his cherished Western idea worked out with painted white men for Indians and painted buttes for a background? Of course, there are photoplays enacted on the Southwestern deserts, with real cowboys and red men for "supers," but somewhere in most of these performances a false note is struck. One who knows the West has little trouble in detecting it.

This, however, is a matter of sentiment, alone. The nebulous ideas most scenario editors seem to have as to rates of payment, and the usually long delay in passing upon a "script," are important details of quite another sort. And, furthermore, it is unjust to throw a creditable production upon the screen without placing the author's name under the title. Of right, this advertising belongs to the author and should not be denied him.

In 1910 a moving picture concern secured a concession for taking pictures with Buffalo Bill's Wild West and Pawnee Bill's Far East Show, and Edwards was hired to furnish scenarios at $35 each. He furnished a good many, and of one of them Major Lillie (Pawnee Bill) wrote from Butte, Montana, on Sep. 2;

"Friend Edwards:

I saw one of the films run off at a picture house a few days ago and I think they are the greatest Western scenes that I have ever witnesed – that is, they are the truest to life. I had a letter from Mr. C – yesterday, and he thinks they are fine.

Your friend,G. W. Lillie."For a time Edwards thought his faith in the moving picture makers was about to be justified. But he was mistaken. He received a check for just $25, which probably escaped from the film men in an unguarded moment, and no further check, letter or word has since come from the company. The proprietors of the Show had nothing to do with the picture people, and regretted, though they could not help the loss Edwards had suffered.

When the moving picture writers are assured of better prices for their scenarios, of having them passed upon more promptly and of getting their names on the films with their pictures, the business will have been shaken down to a more commendable basis. Possibly the film manufacturers borrow their ideas of equitable treatment for the writer from some of the publishing houses.

The "hack" writer, in many editorial offices, is looked down upon with something like contempt by the august personage who condescends to buy his "stuff" and to pay him good money for it. Perhaps the "hack" is at fault and has placed himself in an unfavorable light. Writers are many and competition is keen. Among these humble ones there are those who have suffered rebuff after rebuff until the spirit is broken and pride is killed, and they go cringing to an editor and supplicate him for an assignment. Or they write him: "For God's sake do not turn down this story! It is the bread-line for me, if you do."

Did you ever walk through the ante-room of a big publishing house on the day checks are signed and given out? Men with pinched faces and ragged clothes sit in the mahogany chairs. They have missed the high mark in their calling. They had high ambitions once – but ambitions are always high when hope is young. They are writing now, not because they love their work but because it is the only work they know, and they must keep at it or starve (perhaps and starve).

A taxicab flings madly up to the door in front, and a stylishly clad gentleman floats in at the hall door and across the ante-room to the girl at the desk. They exchange pleasant greetings and the girl punches a button that communicates with the private office of the powers that be.

"Mr. Oswald Hamilton Brezee to see Mr. Skinner."

Delighted mumblings by Mr. Skinner come faintly to the ears of the lowly ones. The girl turns away from the 'phone.

"Go right in, Mr. Brezee." she says. "Mr. Skinner will see you at once."

Mr. Brezee's "stuff" has caught on. Dozens of magazines are clamoring for it. Mr. Brezee vanishes and presently reappears, tucking away his check with the careless manner of one to whom checks are more or less of a bore. He passes into the hall, and in a moment the "taxi" is heard bearing him away.

The lowly ones twist in their chairs and bitterness floods their hearts. Like the author of "Childe Harold," Brezee awoke one morning to find himself famous. These others, with the dingy Windsor ties and the long hair and pinched faces never awake to anything but a doubt as to where the morning meal is to come from.

After hours of waiting in the ante-room, checks are finally produced and passed around to the lowly ones and they fade away into the haunts that know them best. Next pay-day they will be back again, if they are alive and have been given anything to do in the meantime.

Is this game worth the candle? What shall these men do with their "little gift" but keep it grinding, merciless though the grind may be? They cannot all be Oswald Hamilton Brezees.

Before a young man throws himself into the ranks of this vast army of writers, let him ponder the situation well. If, under the iron heel of adversity, he is sure he can still love his work for the work's sake and be true to himself, there is one chance in ten that he will make a fair living, and one chance in a hundred that he may become one of the generals.

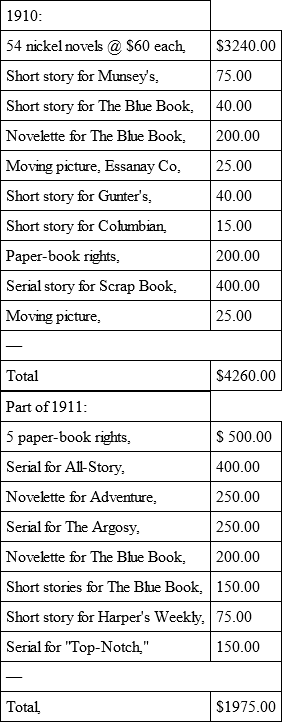

The Factory returns for 1910 and for part of 1911 are given below. Edwards believes that, in its last analysis, 1911 will offer figures close to the ten-thousand dollar mark – but it is a guess hedged around with many contingencies.

George Ade asked an actress, who was one of the original cast of "The County Chairman," to whom he had just been introduced, "Which would you rather be – a literary man or a burglar?" It is related that the actress, who was probably as excited as Ade, answered, "What's the difference?" And this is supposed to be a humorous anecdote!

The man who tells stories, sometimes fiction and sometimes stories, about the Harper publications, evolves the following realistic story about "The Masquerader," originally published in The Bazaar. Well, it seems that one morning, the editor sat her down and found the following letter, which is truly pathetic and possibly pathetically true: "You may, and I hope you have, some little remembrance of my name. But this will be the very oddest letter you have ever received. I am reading that most clever and wonderfully well-written novel, 'The Masquerader.' I have very serious heart trouble and may live years and may die any minute. I should deeply regret going without knowing the general end of that story. May I know it? Will be as close as the grave itself if I may. I really feel that I may not live to know the unravelling of that net. If I may know for reason good and sufficient to yourself and by no means necessary to explain, may I please have the numbers as they come to you, and in advance of general delivery?" The editor sent on the balance of the story, but it was never revealed whether it made the person well again or not. Edwards imagines that the whirl of action in books would not be good for the heart – or, for the matter of that, the soul.

XXV

EXTRACTS

GRAVE AND GAY,

WISE AND OTHERWISE

Cigars on the Editor:

"The berth check came to me this morning. I suppose the cigars are on me. At the same time, there is another kind of check which you get when you buy your Pullman accomodation at the Pullman office in the station. It was that which I had in mind. I suppose the one you enclosed is the conductor's check. I don't believe I ever saw one before."

How "Bob" Davis hands you a Lemon:

"The first six or seven chapters of 'Hammerton's Vase' are very lively and readable – after which it falls off the shelf and is badly shattered. Everybody in the yarn is pretty much of a sucker, and the situations are more or less of a class. I think, John, that there is too much talk in this story. Your last thirty pages are nothing but.

What struck me most was the ease with which you might have wound the story up in any one of several places without in anyway injuring it. That is not like the old John Milton of yore. You used to pile surprise upon surprise, and tie knot after knot in your complications. But you didn't do it in 'Hammerton's Vase' – for which reason I shed tears and return the manuscript by express."

How Mr. White does it:

"I am very sorry to be obliged to make an adverse report on 'The Gods of Tlaloc.' For one thing the story is too wildly improbable, for another the hero is too stupid, and worse than all the interest is of too scrappy a nature – not cumulative. You have done too good work for The Argosy in the past for me to content myself with this… When I return Aug. 9, I shall hope to find a corking fine story from your pen awaiting my perusal. I am sure you know how to turn out such a yarn."

A tip regarding "Dual-identity":

"The story opens well, and that is the best I can say for it. I put up the scheme to Mr. Davis and he expressed a strong disinclination for any kind of a dual-identity story." – Matthew White, Jr.

How Mr. Davis takes over the Right Stuff:

"We are taking the sea story. Will report on the other stuff you have here in a day or two. In the meantime, remember that you owe me an 80,000-word story and that you are getting the maximum rate and handing me the minimum amount of words. You raised the tariff and I stood for it and it is up to you to make good some of your threats to play ball according to Hoyle. It is your turn to get in the box and bat 'em over the club-house. And remember, I am always on the bleachers, waiting to cheer at the right time."

How Mr. White lands on it:

"'Helping Columbus' pleases me very much, and on our principle of paying for quality I am sending you for it our check for $350."

During the earlier years of his writing Edwards made use of an automatic word-counter which he attached to his Caligraph – the machine he was using at that time. He discovered that if a story called for 30,000 words, and he allowed the counter to register that number, the copy would over-run about 5,000 words. At a much later period he discovered by actual comparisons of typewritten with printed matter just the number of words each page of manuscript would average in the composing-room. From his publishers, however, he once received the following instructions:

"To enable you to calculate the number of words to write each week, we make the following suggestions: Type off a LONG paragraph from a page of one of the weeklies that has been set solid, so that the number of words in each line will correspond with the same line in print.

When you have finished the paragraph you can get the average length of the typed line as written on your machine, and by setting your bell guard at this average length you will be able to fairly approximate, line for line, manuscript and printed story.

A complete story should contain 3,000 lines. Calculating in this way, you will be able to turn in each week a story of about the right length. Our experience shows us that the calculated length of a story based on a roughly estimated number of words usually falls short of our requirements, and although to proceed in the manner suggested above may involve a little extra work – not above half an hour at the outside and on one occasion only – by it alone are we convinced that you will strike the right number of words for each issue."

"Along the Highway of Explanations":

"I cannot see 'The Yellow Streak' quite clear enough. You whoop it up pretty well for about three-quarters of the story, and then it begins to go to pieces along the highway of explanations." – Mr. Davis.

Concerning the "Rights" of a Story:

"Unless it is otherwise stipulated, WE BUY ALL MANUSCRIPTS WITH FULL COPYRIGHT." – F. A. Munsey Co.

And again:

"The signing of the receipt places all rights in the hands of the Frank A. Munsey Company, but they will be glad to permit you to make a stage version of your story, only stipulating that in case you succeed in getting it produced, they should receive a reasonable share of the royalties."

The Last Word on the Subject:

"Mr. White has turned over to me your letter of October 12, as I usually answer letters relating to questions of copyright. I think, under the circumstances, if you want to dramatize the story we ought to permit you to do so without payment to us. The only condition we would make would be that if you get the play produced, you should print a line on the program saying, – 'Dramatized from a story published in The Argosy,' or words to that effect." – Mr. Titherington, of Munsey's.

Paragraphing, Politics and Puns:

"Your paragraphs are pretty good, so far. But SHUN POLITICS AND RELIGION in any form, direct or indirect, as you would shun the devil. And please don't pun – it is so cheap." – Mr. A. A. Mosley, of The Detroit Free Press.

Climaxes, Snap and Spontaneity:

"We don't like to let this go back to you, and only do so in the hope that you can let us have it again. The sketch is capitally considered, the character is excellent, the way in which it is written admirable, the whole story is very funny, and yet somehow it does not quite come off. The climax – the denouement – seems somewhat labored and lacks snaps and spontaneity. Can't you devise some other termination – something with more 'go?' This is so good we want it to be better." – Editor Puck.

Novelty and Exhilarating Effect:

"We have no special subject to suggest for a serial, but would cheerfully read any you think desirable for our needs. The better plan always is to submit the first two installments of about four columns each. Novelty and exhilarating effect are desirable." – Editor Saturday Night.

Saddling and Bridling Pegasus:

"We are very much in need of a short Xmas poem – from 16 to 20 lines – to be used at once. Knowing your ability and willingness to accomodate at short notice, I write you to ask if you can get one to us by Saturday of this week, or Monday at latest. I know it is a very short time in which to saddle and bridle Pegasus, but I am sure you can do it with celerity if any one can." – Editor The Ladies' World.

Carrying the Thing too Far:

"We regret that we cannot make use of 'The Brand of Cain,' after your prompt response to our call, but the title and story are JUST A LITTLE BIT too sensational for our paper, and we think it best to return it to you. It is a good story and well written, but we get SO MUCH condemnation from our subscribers, often for a trifle, that we are obliged to be very careful. Only a week or two ago we were severely censured because a recipe in Household Dep't called for a tablespoonful of wine in a pudding sauce, and the influence of the writer against the paper promised if the offense were repeated." – From the editor of a woman's journal.

And, finally, this from Mr. Davis:

"We are of the non-complaining species, ourself, and aim only to please the mob. Rush the sea story. If it isn't right, I'll rush it back, by express… Believe, sir, that I am personally disposed to regard you as a better white man than the average white man because you a larger white man, and, damnitsir, I wish you good luck."

XXVI