Waves Across the South

Fig. 2.9 ‘King George. N. Zealand Costume’ by Augustus Earle (1828)

2.9 © Augustus Earle, National Library of Australia, NK12/84

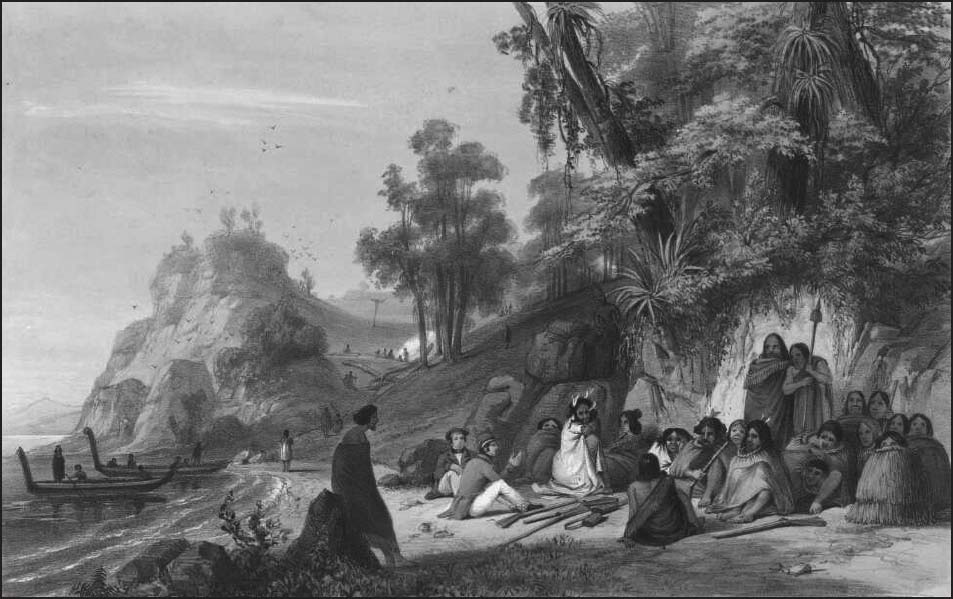

Fig. 2.10 ‘The wounded chief Honghi [Hongi Hika] & his family’ by Augustus Earle, 1827

2.10 © Icas94 / De Agostini / Bridgeman Images

The so-called ‘Māori Napoleon’, Hongi Hika (1772?–1828), was an early initiate to the power of European muskets. Hongi used muskets in the wars between Nga Puhi and Ngati Whatua in the Bay of Island district of North Island.[106] The loss of the Nga Puhi in a battle of 1807 or 1808, which killed two of his brothers and many chiefly kin, was a formative moment in his life. Travelling to Sydney, on a missionary ship, he supported the first missionary settlement in New Zealand. This missionary settlement was later criticised for being under his personal monopoly.[107] Hongi’s relationship with the missionaries lasted until his death.

As a Māori account holds, Hongi operated within established ways of avenging the wrongs against kin:

The primary reason Hongi set himself up as a war leader killing people was the wrongs of former times, that is the farewell requests (concerning them) of those who died earlier, which Hongi carried out to honour the words of his ancestors who died.[108]

Yet Hongi innovated and changed these traditions. Following the Europeans’ advice he grew wheat and corn, and potatoes, that he could use to buy muskets and gunpowder from arriving vessels, and he put the captives he took in war to work on these plantations.[109] As a result of these wars, and the interplay of new and old, Hongi’s people came increasingly to refer to themselves using a larger collective name, ‘Nga Puhi’.[110]

Hongi created quite a stir when he arrived in London in 1820 accompanied by the evangelical Thomas Kendall and an aide, Waikato [Fig. 2.11]. Global travel supercharged Māori customary practice. Tellingly he was presented to the British monarch, George IV. He allegedly observed: ‘There is only one king in England, there shall be only one king in New Zealand.’[111] He also spent some time at the University of Cambridge, was entertained by the Vice Chancellor and helped create a Māori dictionary.[112] In the oral tradition of his descendants, he is said to have taken a great interest in maps of the Napoleonic wars deposited in Cambridge.[113] A representation of Hongi’s face had arrived in England prior to his person. Marsden had asked him to carve a likeness of himself; a copy of the carving was later published in the Missionary Register of 1816.[114] One MP wrote of Hongi’s appearance in the House of Lords and compared his face to a carved specimen:

Fig. 2.11 ‘Waikato, Hongi Hika and Thomas Kendall’ by James Barry, 1820

2.11 © Barry, James, active 1818-1846. Barry, James: [The Rev Thomas Kendall and the Maori chiefs Hongi and Waikato]. Ref: G-618. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/23241174

I went round, and got near enough to touch his Majesty; when I found his royal face to be one of the very finest specimens of carving I have ever beheld. The Chamberlain’s face [Waikato] was fair; the sunflowers on it were highly respectable; but the King’s nose, which surpassed the average size, was one blaze of stars and planets.[115]

When he returned to New Zealand, the fact that he came with gifts and patronage and a personal bond with the British Crown allowed him to immediately mount a series of campaigns to consolidate his power. He traded many of his presents in Sydney on the way back to New Zealand, preferring muskets, powder and shot. (He had hundreds of muskets in his possession when he returned to New Zealand.) He retained a suit of armour which was presented to him.[116]

Hongi’s story is reminiscent of that from Tonga: local wars were part and parcel of the global contests of the age of revolutions. For the spread of armament, political consolidation and notions of community arose at the intersection of Māori traditions and British imperialism in a mutually reinforcing dynamic. Such a dynamic was evident with respect to the interpretation of Hongi’s face: it was a product of Māori carving as much as European notions of race. Hongi Hika’s wars in the 1820s covered a wide area, allowing hundreds of people to leave the Bay of Islands, and, according to one historian, ‘set almost the whole of the North Island on the move, caused numerous wars and expeditions in both the North and South Islands, and eventually brought about a major redistribution of population’.[117]

In extensive and often negative European commentary appeared another iconic fighter of the musket wars.[118] Te Rauparaha (?–1849), the Ngati Toa leader, was involved from the late eighteenth century in a series of war parties to right the wrongs done to his people. He extended his expeditions south, in order to find a home for his people. His iconic status is illustrated in how his dance of war and welcome, ‘ka mate’, is now used widely by the All Blacks rugby union team, a signifier in its original sense of the triumph of life over death that has now become a cultural symbol of the Māori to millions of rugby fans. He reached down to Kapiti Island, close to today’s Wellington at the southern end of North Island, and established a base there.

It was partly as a result of European assistance that Te Rauparaha’s migratory wars spread into the South Island though he came from the North Island. His son, Tamihana, a Christian convert and one of the first Māori to enter a missionary school, wrote of the events which unfolded when John Stewart of the Elizabeth arrived at Kapiti island in 1830. Te Rauparaha asked the captain whether he would transport him and a war party to Akaroa, close to today’s Christchurch on the South Island, to right the wrongs caused by some murders. Te Rauparaha took seventy fighting men with him aboard the Elizabeth, and Stewart participated in a scheme whereby the offending chief Tamaiharanui was lured aboard. Stewart called out to Tamaiharanui’s people: ‘Go and bring him to get some gunpowder.’ In Tamihana’s words:

When his canoe reached the ship, Tamaiharanui, his wife and daughter came aboard and went below to the captain’s quarters. When Tamaiharanui had sat down Te Rauparaha tied his hands and took him and his family to another cabin. Nothing was said. Then Rauparaha came up on deck with his warriors to capture the 30 men who had accompanied Tamaiharanui; not one escaped. When it was dark the 70 warriors got in the canoes and went ashore. They entered the villages at dawn, the slaughter began.[119]

With time, the extent of Te Rauparaha’s contact with whalers expanded greatly and Europeans readily transported his canoe aboard their ships.[120] Widening his reach by foreign assistance, Te Rauparaha followed the path earlier trodden by Hongi and other Māori, arriving in Sydney and meeting Marsden in 1830. He also came into dispute with the New Zealand Company, formed to create settlements for British migrants. Te Rauparaha attacked land surveyors, ending with the killing of the Company’s Captain Arthur Wakefield (1799–1843).[121] These disputes over land point to the connection between this period of war and trade which pitted Māori against outsiders and what was to come in terms of colonial settlement, when Te Rauparaha signed a copy of the Treaty of Waitangi.[122]

So far, two steps in the sequence of change in New Zealand are clear. First, the encounter with the British transforms existent customs connected to righting the wrongs of the past. Second, the spread of weapons and the entrenchment of violence make their impact on these existent customs. Warriors and monarchic figures emerged who used the British to expand their ambitions. Te Rauparaha employed the transport provided by the invaders in this way. And at the same time British bureaucracy and law arrived in New Zealand. It presented itself as keen on protecting Māori, even from the effects that Europeans were having on their land.

In 1814, the year of his arrival in New Zealand, as part of the first contingent of missionaries, Thomas Kendall was appointed Justice of the Peace.[123] The British created a position of Resident to New Zealand, taken up by the Tory James Busby in 1833, who was seen by the Māori as the British ‘king’s man’, just as men-of-war were called the ‘king’s ships’ and their sailors the ‘king’s warriors’.[124] The British empire could in this way project the language and symbolism of monarchy for its own imperially benevolent purposes. Busby’s letter of appointment from the governor in Sydney made specific reference to how the Elizabeth had contributed to the wars of New Zealand. He came to New Zealand in the direct context of that violent episode in 1830.[125] Busby arranged for a Māori flag, previously used by the missionaries, to be flown by vessels built in New Zealand as they entered Sydney, as ‘the Flag of an Independent State’. A declaration of Māori independence was also signed by fifty-two chiefs by the end of the 1830s in the name of ‘The United Tribes of New Zealand’.[126] It was first signed by Māori chiefs in 1835.

The 1835 declaration was conceived by Busby as a ‘Magna Carta of New Zealand Independence’, though it was clearly a first step on the way to formal British control.[127] Busby saw a confederation of chiefs as the constitutional body of the Māori people and wrote soon after his arrival that he wished to build a Parliament House for the Māori chiefs.[128] His view was that they were the ‘aristocrats’ of their society, under the absolute power of the primary chief, who functioned like a king.[129] He hoped to school these chiefs in keeping the peace and in moral principles of government. In return they were to be awarded a salary and a medal marking their distinction.[130] The Resident, the post that Busby filled, would legislate and present the congress of chiefs with the laws needing approval. This British representative would seek the advice and information of missionaries and other settlers. A militia, composed of settlers who could act in an emergency or a trained ‘native force’, were also part of Busby’s vision. In conceiving of his post in these terms, Busby took up the role played by Marsden’s religious mission. He bitterly complained at times that the missionaries of New Zealand did not defer to him.[131] He also diverged from his orders from Sydney. The governor in New South Wales criticised the 1835 declaration for vesting exclusive legislative power in the confederation of chiefs.[132]

Despite the liberal humanitarian discourse, the 1835 declaration arranged by Busby was partly a strategic response to the manoeuvring of a French aristocrat, Baron Charles Philip Hippolytus de Thierry, from a family who had fled the French Revolution, who threatened to found a colony in New Zealand, free from taxation. The baron planned for marriage and collaboration between Māori and Europeans. Before the 1835 proclamation, in the early 1830s, a direct petition had been drawn up by the Māori chiefs and addressed to the British king, William IV and it specifically referred to French plans:

We have heard that the tribe Marian [a reference to Marion du Fresne, the French explorer who was killed by the Māori in 1772] is at hand coming to take away our land, therefore we pray thee to become our friend and the guardian of these islands, lest the teasing of other tribes should come near to us, and lest strangers should come and take away our land. And if any of thy people should be troublesome or vicious towards us (for some persons are living here who have run away from ships), we pray thee to be angry with them that they may be obedient, lest the anger of the people of this land fall on them.[133]

In the mid 1830s Thierry sailed through the Pacific, after offering a colony to both the Netherlands and France, and he wrote from Tahiti to the British Resident of New Zealand, styling himself ‘Sovereign Chief of New Zealand and King of the Island of Nukahiva [in the Marquesas, which he had claimed in the course of his voyage]’. It was in response to this eccentric French bid, and the growing worry about both French and American interests in New Zealand, exemplified by French Catholic missionaries and by American whaling, that Busby presided over the proclamation of the sovereignty of the united tribes.[134]

Busby also noted how two Belgian brothers were buying land in New Zealand and how a ‘Polish Count’ was writing of his travels in the country.[135] French Catholics in New Zealand, meanwhile, were said to be joining forces with the Irish; and a Catholic bishop was alleged to be plotting the arrival of a vessel of ‘Soldiers and Missionaries and traders’ for the formation of a French settlement.[136] The way in which humanitarianism cloaked strategic imperial calculations is especially evident in Busby’s bid to educate ‘half-caste children’ lest they fall into the grip of Roman Catholics in Aotearoa/New Zealand and be educated in ‘sentiments and principles adverse to British interests’.[137] In one instance of the prevalent paranoia, which in this case was linked to revolt in the Americas and was racist, Busby wrote to his brother of ‘American negroes from the whalers’ who he had found teaching voodoo to Māori in the bush:

Here were some twenty or thirty Natives of New Zealand seated round the side, and in the middle was a sort of brushwood altar with some articles on it, and busy about it three or four Negroes, who were, by signs, apparently instructing a New Zealand tohunga in some mystic rite. With the New Zealanders were four or five white men from near Hokianga who were known to me as being undesirable characters, and these men were already under the influence of an intoxicant.[138]

With such a dizzying range of global interests at play, which are consistent with the age of revolutions, the scene was now set for the controversial Treaty of Waitangi of 1840. Like the treaty arranged by Busby in 1835, the Treaty of Waitangi was framed with a dual purpose: while establishing the legal independence of New Zealand, it also sought to bring the islands under British protection. The balance between these two aspects of the treaty is what has caused protest ever since it was signed, resonating until this day in rival land claims. The most debated words of the treaty are: ‘to the Chiefs, the Tribes, and all the people of New Zealand, the entire supremacy of their lands, of their settlements, and of all their personal property’.[139] At the heart of the paradox lies the relationship between ideas of kinship and kingship.

Māori imagined that they were binding themselves to a familial relationship with the British, and choosing them over the French, the ‘tribe of Marion’. Māori kinship with the British was seen to come from shared ancestry and religion. This relatedness allowed them also to become kings. In 1839 they had the idea of a meeting ‘for the election of a king’.[140] In commenting on Māori bids for kingship, however, Busby wrote: ‘I believe we are all agreed that a King from amongst themselves is quite out of the question.’[141] To his brother he noted that a Māori chief had alluded to how Busby himself may be their king: ‘I told him that the “ritenga” [custom] of this land was not to have a King, that the authority must be in the confederation of chiefs.’[142]

The 1835 declaration called upon the British king to be ‘the parent of their infant state’.[143] This language arose directly from the Māori chiefs.[144] The reason Busby did not support a Māori king or even himself as king, was because for the British, who were now annexing territory, ultimate sovereignty did not reside with Māori chiefs. Rather it lay far away with Queen Victoria, now the British monarch, and was delegated by her to her representatives in New Zealand and Sydney. Chieftaincy could continue but only under subordination to Victoria. Notions of independence were a façade that propped up a counter-revolutionary empire, an empire which reactively adopted the language of politics and independence of this period.

In the decades that followed, it was no wonder then that Māori involved themselves in a series of skirmishes with the British. They too could be monarchs. The ‘King Movement’ or Kīngitanga appointed the first Māori king in the late 1850s and opposed the take-up of ancestral land by the British empire. It successfully mounted armed resistance against the British. It declared the boundaries of the Kīngitanga, or kingdom in 1858. The movement expected to govern alongside the settler state. Intriguingly, Kīngitanga could creatively adopt the narrative of the age of revolutions: for instance, the Haitian Revolution became a point of reference to the Kīngitanga movement. Haiti was interpreted from a Māori cosmology: Haitians had built a pa on a hill (fortification), from where they had flown their kara (flag), calling the French to attack them. ‘Now that island possesses law and its independence [rangatiratanga] is established; its flags have been raised; also, the councils [runanga] of that place are working for the good of the country. The chiefs [rangatira] have united their word; the law has effect; its many harbours are rich.’[145]

A change in the order of politics had come to pass in slow motion and through the evolution of established concepts such as iwi, hapu and intra-tribal identity, as well as war and Māori attempts to respond to British and global ideas and events. When the British state intruded it did so by cleverly adopting the instruments of the age of revolutions to counter their revolutionary power, from declarations of indigenous independence to flags. And Māori too adopted the mantle of monarch and the legacy of the age of revolutions, including on one occasion events in Haiti, to respond to the British. Yet the fact that similar types of political consolidation were occurring elsewhere in the Pacific makes this more than a Māori story. It is a feature of these years in the Pacific. Arms and ideas, Christianity and the British state, Anglo-French rivalries and shared aims forged these changes. But these changes were not created simply by outside forces; rather change drew in Māori and Pacific political vocabularies. The British were able to use the result of these encounters for imperial gain.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.