Waves Across the South

RAIDING EUROPE

In 1806, more than a decade after d’Entrecasteaux’s time in Tonga, an Englishman called William Mariner was taken captive in the Tongan islands, at the age of fifteen, to the north of where d’Entrecasteaux made his observations. Mariner arrived on the Port au Prince, a private English ship, which was formerly French, and which was now deployed to raid French or Spanish vessels. The sailors on board were allowed to keep the booty. The ship was ‘nearly 500 tons, 96 men, and mounting 24 long nine and twelve pounders, besides 8 twelve-pound carronades on the quarter-deck’.[58] It was because of vessels like this that the French feared that La Pérouse had met a death at the hands of English anti-republicans. Spanish bases in the Americas were particular targets of the Port au Prince but so were the whales that roamed the Pacific and which were valued for their oil.

In Tonga, the Port au Prince was taken over by about 300 islanders who went aboard the ship and attacked the surprised crew. This was in spite of the warnings that there was a conspiracy to take over the vessel; these warnings were issued by some Hawai‘ians (who understood Tongan) and who were part of the Port au Prince’s crew. The Tongans eventually grounded the ship. Gunpowder, carronades, guns and stripped iron were taken ashore, and after the ship had been summarily looted for everything that was deemed valuable it was burnt. About half of the crew were massacred by the Tongans in what followed. According to Mariner, the attack was led by a Hawai‘ian, who probably arrived in Tonga on an American ship.[59] Mariner wrote evocatively of the noises that were let off by the guns on board:

In the evening they set fire to her, in order to get more easily afterwards at the iron work. All the great guns were loaded, and as they began to be heated by the general conflagration they went off, one after another, producing a terrible panic among all the natives.[60]

The survivors, their skills and their possessions were recycled in the wars that gripped Tonga around the decline of chiefly lines and before the consolidation of George I’s monarchic state. The story goes that the future George I was himself involved in the raid of the Port au Prince, when he was about nine, and that he nearly drowned in the whale oil in the hold of the vessel.[61] Mariner was a key asset. He was so liked by the chief Finau ‘Ulukalala II – who raided the ship – that he was adopted by one of his wives. Another of the survivors of the Port au Prince was serving as ‘prime minister’ to a chief on Vava‘u as late as 1830.[62]

From his base in the Ha’apai islands ‘Ulukalala wished to attack the political centre of these islands in Tongatapu from where he had been driven away. In seizing the Port au Prince he was arming himself for his wars with the powers that be in Tongatapu. Mariner and fifteen other Britons participated in the raid that followed on Tongatapu, undertaken with the use of a fleet of canoes and the carronades looted from the Port au Prince.[63]

In the end one of the most important forts at Nuku’alofa, now the capital of Tonga, fell into the hands of ‘Ulukalala’s forces. Mariner described the fort as made of walls of wicker-work supported by posts, making nine-foot high fences; it had stood for eleven years but was now ravaged. It was a truly awful rout: ‘The conquerors, club in hand, entered the place in several quarters and slew all they met, men, women and children.’[64] These inhabitants were awe-struck by the new weapons used by their assailants. They described balls as if they were alive, entering houses, going around their dwellings looking for someone to kill, rather than exploding straight away. While the battle was in progress, ‘Ulukalala sat himself in an English chair taken off the Port au Prince and surveyed the scene from the reef.[65] After this attack, his further attempt to take the fort in Vava‘u harbour was not as successful.

Despite using European articles of war, ‘Ulukalala preferred Tongan military customs and did not take the advice that Mariner gave him on how to consolidate his power. When at peace, he took up the opportunity for conversation with Mariner to learn about the outside world, and one topic that was particularly interesting was that of politics. He wished to be the king of England. This again highlights how islanders were taking up new notions of monarchy:

Oh, that the gods would make me king of England! There is not an island in the whole world, however small, but that I would then subject to my power: the King of England does not deserve the dominion he enjoys; possessed of so many great ships, why does he suffer such petty islands as those of Tonga continually to insult his people with acts of treachery? Where [sic.] I he, would I send tamely to ask for yams and pigs? No, I would come with the front of battle; and with the thunder of Bolotane [the noise of the guns of Britain].[66]

A central component in the spread of the global market into Tonga was also tied up with these conversations. For Mariner explained the role of money to his patron. He explained that the silver discs that had been taken off the Port au Prince by the Tongans and which had been thrown and bounced across the surface of the sea, and called flat stones or pa’anga, were in fact money. Pa’anga is now the currency of Tonga; it was introduced as such in 1967.[67]

When ‘Ulukalala died, Mariner was also highly favoured by ‘Ulukalala’s son, Moengangongo.[68] Mariner finally escaped in 1810. Though wishing to escape before this point, he had not been at the right place at the right time to intercept a vessel. When he left, it was a painful parting because he had integrated himself into Tongan ways.

In 1832, Mafihape, Mariner’s adoptive mother in Tonga, sent him an intriguing letter.[69] In her letter, written or probably transcribed for her by someone very familiar with Tonga, she notes that ‘everyone has become a Christian’. She asks Mariner to send a ship:

If you have genuine affection [for me] it would be wonderful if you could send your younger brother, if you have one – or your son, if you have one, so I can see him, and also so that you be shown, in the Lord, to be manly – if you are so determined not to come yourself and see me. He can come and live here instead.[70]

Mafihape herself had by this time converted to Christianity but wanted Mariner to know that she was ‘very poorly off’. Despite the spread of a new religion, and its associated trappings of paper and writing, as also new conceptions of behaviour, Mafihape still hoped to utilise the customs of chieftaincy, where chiefs adopted powerful sons, to circumvent her allegedly lowly situation. Her plan was to arrange for a rerun of William Mariner’s time in Tonga, by asking for the arrival in Tonga of Mariner’s younger brother or son, and perhaps even hinting that Mariner himself should return. Her letter points back to patterns of chiefly rule, which pre-dated contact, while also bearing the markers, in the use of ‘in the Lord’ in the extract, of newly Christianised Tonga.

In the course of investigating the disappearance of La Pérouse in the mid 1820s, Peter Dillon records meeting this woman and showing her the portrait of Mariner. Dillon writes that she exclaimed ‘it is Tokey’, the name that ‘Ulukalala gave to Mariner, in remembrance of a favourite child of his who had died. She ‘wept bitterly’ at the sight of the image. In Tonga today the story is told that she may have been Mariner’s concubine rather than his adoptive mother.[71]

Sadly, Mariner could not read Mafihape’s letter having forgotten most of his Tongan. He complained that the ‘orthography’ of his mother’s letter was in too unfamiliar a form, indicating the impact of the English missionaries, perhaps.[72] After returning to England, he gave up his life of adventure and became a stockbroker in London, married and fathered eleven children and, rather unfittingly, drowned in Surrey Canal at the age of fifty-three.[73] In the Pacific meanwhile there is a line which carries the name Mariner, from Mariner’s son George, who settled in Samoa with a Tongan wife. As for Mariner’s own end in the canal, a speculative Tongan theory is that he committed suicide, being unable in the end to come to terms with his life in England.[74]

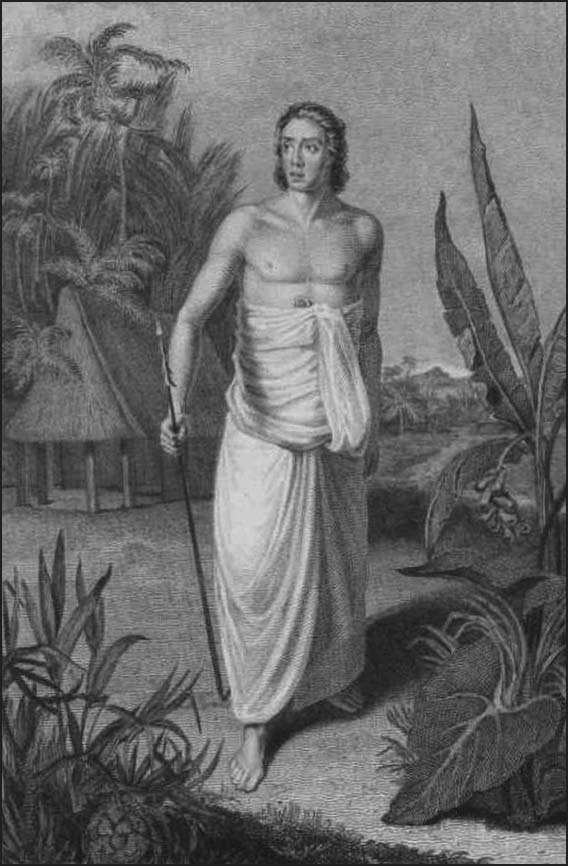

Fig. 2.5 ‘Mr. Mariner in the Costume of the Tonga Islands’ (1816)

2.5 © The History Collection / Alamy Stock Photo

William Mariner’s account of travels was written up for him by a doctor, John Martin, citing the excuse that Mariner had become so accustomed to Tongan ways that he had been out of the habit of writing and reading in English. The image facing the title page is a full-length view of Mariner, which was shown by Dillon to his Tongan mother, dressed in Tongan clothes and bare-bodied above the waist like the women who danced for d’Entrecasteaux. [Fig. 2.5.] Mariner had straddled worlds. A product of the European age of revolutions, and its commitment to global war at any price, he had been taken captive to fight in a series of other wars, which were Tongan tussles in aid of monarchy. These wars too, arose within the changing political currents of this period. The age of revolution had bred a surge of indigenous monarchism in the Pacific.

Fig. 2.6 The beach where the ship is said to have been raided (above) and the Port au Prince Memorial (below), Tonga

2.6a © Sujit Sivasundaram

2.6b © Sujit Sivasundaram

The dispersal of European weapons was critical to the story around the Port au Prince; so it is appropriate that three of the cannon from the Port au Prince are today placed in front of the former site of the British High Commission in Tonga. Other cannon are dispersed elsewhere including on Ha’ano where, according to one story told by the inhabitants of this island in the Ha’apai group, the ship was finally taken.[75] In 2012, the discovery of a sunken ship thought to be the Port au Prince gave rise to a treasure hunt in the waters off Tonga.[76] Today, in Ha‘apai, which I visited in 2017, stories still circulate about the site of the Port au Prince wreck, together with accounts of how the Japanese mafia as well as New Zealand criminals had found gold from the wreck and taken it out without the knowledge of the Tongan government. A monument has been erected close to the beach where the Port au Prince was raided. It is overtaken by the lush vegetation of Ha‘apai. [Fig. 2.6]

The beach itself is simply a thin strip of sand, bearing no evidence of its history. However, perhaps fittingly, given the history of exchanges on Tonga, including of animals brought by voyagers, there was a dead pig floating in the water when I walked its sands. The carcass was accompanied by plastic bottles, broken coral and fallen coconut trunks rotting in the water. The signs of modern consumption – part of the history that followed the whale oil on the Port au Prince – were evident on the beach.

When published, Mariner’s account was one source of inspiration for the poet Byron’s idyllic description of South Pacific island culture. ‘The Island’ was written in 1823. In Byron’s telling of the politics of Tonga, republicanism is rife on the island of Toobonai, the fictional island where the poem is set. It is the ‘equal land without a lord’.[77] Here nature is bountiful and the islanders are relatively uncorrupted by sin. Labour is unnecessary because of what nature provides:

Where all partake the earth without dispute,

And bread itself is gather’d as a fruit;

Where none contest the fields, the woods, the streams: –

The goldless age, where gold disturbs no dreams,

Inhabits or inhabited the shore,

Till Europe taught them better than before:

Bestow’d her customs, and amended theirs,

But left her vices also to their heirs.[78]

This is a telling fact of the contradictory effects of the age of revolution on either side of the world: European literary representations, full of romanticism, could be utterly disconnected from the reality of the Pacific. If Tongans raided Europe to remake their politics, Europeans in turn often missed the import of what was happening in the Pacific in the age of revolutions.

The need to challenge European depictions of this sequence of events is clear in the writings of recent Tongan historians. They react against a view of the burning of the Port au Prince as indicative of the ‘treachery’ of Tongans: instead they hold that the crew of this vessel behaved ‘like pirates and robbers’ in the first place.[79] In other words, these were two systems of raiding, European and Tongan, which faced each other around the Port au Prince. The two-way exchange included materials, ideas and culture, too.

AOTEAROA AND THE IMPERIAL MONARCHS

This indigenous language of political consolidation and monarchy usefully fed into the advance of the British empire. In looking further south, to Aotearoa/New Zealand, the forward march of the British is in full show. The story from New Zealand that follows corresponds with some of the features of the transformation in Tonga with the consolidation of monarchy.

First, customary forms of warfare, chieftaincy and decision-making evolved in contact with British traders and missionaries. Second, warfare spread in range and intensity as exchanges with Europeans deepened and as weapons and affiliations proved politically useful as signs of mana (status) to Māori rangatira (chiefs). Third, and in contrast with Tonga, the British state came in claiming to protect Māori through the introduction of law and bureaucracy. There were plans for flags and discussions of constitutional arrangements, set piece indicators of the age of revolutions and the dawn of our times. Fourth, Māori asserted their standing as political agents able to resist the British, sometimes picking up on the tactics of the revolutionary era, for instance through the identification of a Māori monarch. If the articulation of monarchy occurred across the Pacific, this in turn allowed bigger monarchs or the British empire to rise up as a counter-revolutionary force. The 1840 Treaty of Waitangi saw the status of the political elites of New Zealand tied up with that of the British monarch.

In general terms across the Pacific, the number of settled Europeans was dramatically increasing as the nineteenth century began. In Hawai‘i, while there had been ten European residents in 1790, there were nearly a hundred by 1806.[80] In Tonga a visiting captain wrote in 1830 that there were many Englishmen in the islands, who had been treated with great kindness, and who had married, settled and accommodated themselves to Tongan manners and customs.[81] By the late 1830s there were as many as two thousand Europeans settled in New Zealand, including missionaries, and ‘beachrangers’, meaning people who were cast out of sealing and whaling missions for various crimes, and escaped convicts. The greatest concentration of these settlers resided in the Bay of Islands district in the North Island.[82] Occasional and exoticised encounters gave way to more sustained contact, and formal imperial takeover was just around the corner.

After the British established a base for themselves in Australia in 1788 and in Tasmania by 1803 the game of imperial takeover had begun. This game saw New Zealand following a different course to Tonga. One vital difference between the two was the closeness between Australia and New Zealand, which made New Zealand a resource frontier for Australia. The significant turning point for imperial advance was the British signing of the Treaty of Waitangi with Māori chiefs in 1840, which the colonists interpreted as a deed of cessation. The French responded by annexing the Marquesas in 1842 and Tahiti in 1843. Though a tit-for-tat battle for islands marked Anglo-French relations in the Pacific through the course of the mid to late nineteenth century, the convict colony that the British had established in Australia in the eighteenth century meant that the Pacific came increasingly under the purview of the British.

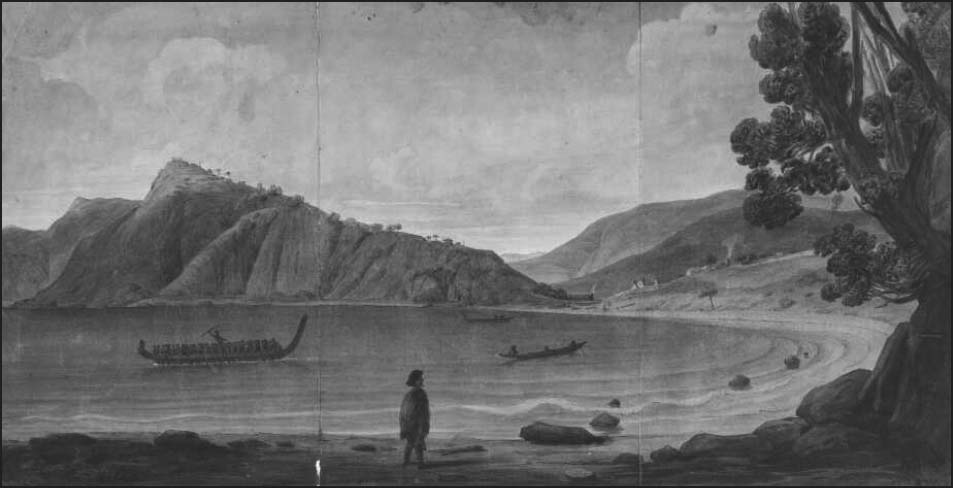

One source for the early history of New Zealand is the travelling writer and painter Augustus Earle, who visited in 1827–8. Despite the increasing presence of Europeans, Earle’s watercolours of the Bay of Islands show romanticised scenes of nature and Māori going about their business while paying no attention to arriving European ships. These visual illustrations do not exaggerate the impact of styles of European settlement on Māori habitation and deserve scrutiny for revealing indigenous social and political features which sometimes go missing in the textual sources kept by Europeans.[83] One large watercolour shows Te Puna in the Bay of Islands. Māori canoes and a large tree in the foreground play a bigger role than the missionary settlement behind the beach: no Europeans are in sight. [Fig. 2.7][84] A pa or Māori defence fortification appears at a height on the hill above the bay. In keeping with such a reading of this image, it is important to insist that prior forms of organisation, navigation and politics in New Zealand set the terms for early encounters with Europeans. For instance, existent systems of patronage allowed missionary work to proceed under the powerful auspices of Māori chiefs.[85]

Fig. 2.7 ‘Tepoanah Bay of Islands New Zealand a Church Missionary Establishment’ (watercolour, Augustus Earle, 1827)

2.7 © Augustus Earle, National Library of Australia, NK12/139

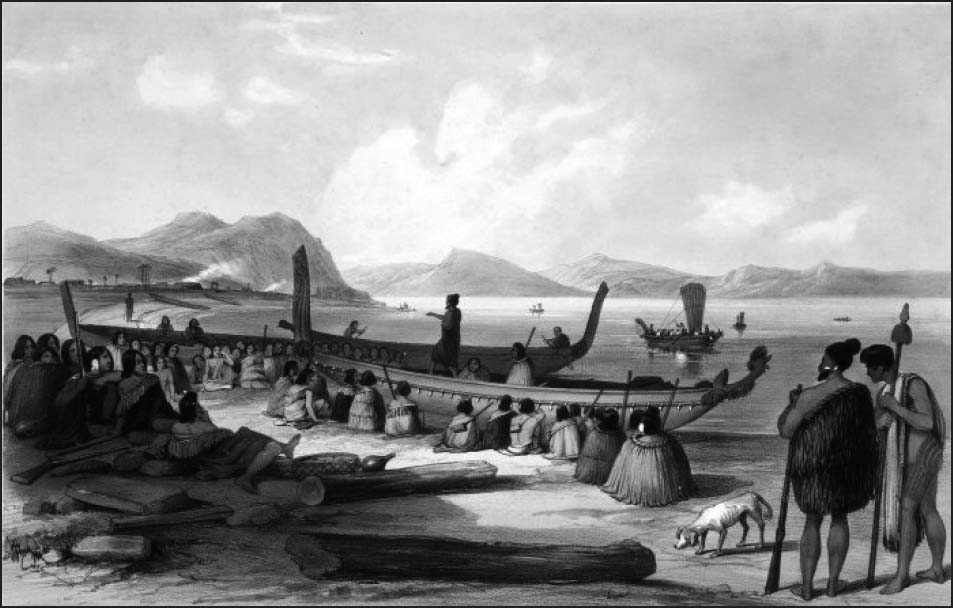

Fig. 2.8 ‘War speech’ by Augustus Earle (published 1838)

2.8 © Augustus Earle, National Library of Australia, NK 668

In one offensive myth, these islands are a nation founded by Captain Cook. It is true that the Endeavour voyage gave rise to remarkably accurate charts of the coast of New Zealand in 1769–70.[86] Yet this is an offensive narrative because ideas of people were long extant in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Iwi denoted people of common descent, a fundamental identity, tied up with the arrival of Māori from a place denoted as Hawaiki. In political terms Māori also organised for warfare in hapu, groups subordinate to chiefs, fighting as units.[87] Plans for war were made and discussed in various kinds of ceremonial meetings, which early missionaries called ‘councils of war’ and which Earle called ‘a rude parliament’.[88] [Fig. 2.8][89] Whakapapa are Māori genealogies. Teachers and experts in Māori genealogy possessed genealogical staffs that were notched with references to their ancestors, providing a means for keeping up a sense of their past.

European observers were quick to interpret and exaggerate traditional styles of Māori war – caused by the resolution of wrongs that resulted from the killing of high-ranked individuals, or from offence to the sacred or untouchable status of elites. Europeans saw these conflicts as signs of the ‘savagery’ of Māori. The resulting view of the ‘heathen’ Māori was central to the early colonisation of New Zealand. As time passed there was also the trope of the enfeebled Māori, which justified liberal protectionist empire.[90] Religious encounter and rapacious trade oiled these tropes.

The taking of the Gospel to New Zealand was pushed through by Rev. Samuel Marsden, an Anglican cleric and a Yorkeshireman who engaged in extensive agricultural pursuits in Paramatta, now a suburb of Sydney. Under Marsden’s auspices, the first evangelical contact with New Zealand was made in 1814, in a vessel captained by Peter Dillon who appears again in our story.[91] Marsden was troubled by the brutality of European–Māori interaction and stated his agenda as a making of peace.[92] He took a liking to Māori who came to Sydney and saw their land as a ‘great emporium of the South Seas’.[93]

In 1809 the Boyd, a vessel on its way to London with sixty Europeans, was returning a Māori chief Te Aara to New Zealand when it was raided at Whangaroa in the Bay of Islands district. Its passengers were killed by Māori, including women and children. Another vessel under the command of the Sydney trader Alexander Berry, who was procuring spars for the Cape Colony, was only able to rescue a woman, two children and a boy from among the Boyd’s passengers.[94] Marsden presented his own view of the violent episode around the Boyd in the Sydney Gazette, using the account of a Tahitian called ‘Jem’ who deserted a European ship.[95] Berry’s and Marsden’s views of the civilisational capacity of the Māori differed; authoritarian settler politics were aligned against reformist Christianity in these two alternative renditions.[96]

One contemporary explanation of the cause of the attack is that the master of the Boyd had been especially harsh to the returning Māori chief, Te Aara, in the course of the voyage. In conversation, Earle noted that one of his interlocutors, ‘King George’ [Te Uri-Ti], mimicked the ill-treatment of the returning chief on board the ship, ‘his cleaning shoes and knives; his being flogged when he refused to do this degrading work’.[97] Another explanation is that Te Aara was dismayed by the death of his relatives in New Zealand, brought about by the spread of European diseases.[98] Cultural misunderstanding ran ahead of the Boyd’s problems. This included a pocket watch accidentally dropped into the waters by a visiting captain, which Māori believed cursed the coast with disease. A group of two hundred whalers decided to exact revenge, massacring the settlement of Marsden’s friend Te Pahi, who had spent time in Sydney, meting out their revenge on the wrong group of islanders.[99] Such dramatic altercations changed Māori–British politics.

Yet the idea of the violence of Māori culture and its interaction with ruthless and unthinking Europeans, in a cycle of revenge and counter-revenge, is a rhetorical relic of the period. To the contrary, Māori were mobile peoples who undertook war in order to restore their integrity and status.[100] If there was no possibility of war against offenders, war could be undertaken against distant non-kin to this end of restoration. The arrival of Europeans expanded these customary forms of politics in new directions, making wars more intense and wider in their radius. As in Tonga, the appropriation of European weapons was significant. Newer styles of war, sometimes termed ‘muskets wars’, unified and concentrated power.[101] They generated unprecedented fatalities and a decline in population. But they transformed what already existed by way of conflict rather than giving rise to a simplistic fatal impact with no room for indigenous response.

The physical power of muskets was not the sole determining factor of these wars. Some historians have cast the new culture of the potato as equally significant as muskets to the unfolding of these wars – in providing food to enable long-range war parties. [102] In the words of the first British Resident of New Zealand in 1837: ‘there seems to be good reason to doubt whether their wars were less sanguinary before Fire Arms were introduced.’[103] Established military tactics involving close combat, evolved in order to accommodate these new long-distance weapons.[104] The symbolism of these muskets was critical too. Particular chiefs, who acquired weapons, were cast as great leaders and warriors; they could be seen as operating within pre-existent modes of righting wrongs. Gradually, over the decades that followed, and beyond the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, the concept of the Māori monarch appeared as a result of this entanglement between old and new, the Pacific and Europe. As an example of the attribution of monarchy, Earle drew ‘King George’ or ‘Shulitea’ (Te Uri-Ti), who served as his friend and protector in New Zealand.[105] [Fig. 2.9]