Waves Across the South

WAVES ACROSS THE SOUTH

A New History of Revolution and Empire

Sujit Sivasundaram

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2020

Copyright © Sujit Sivasundaram 2020

Cover images © The Picture Art Collection/Alamy Stock Photo; josefstuefer/Getty Images; DEA/BIBLIOTECA AMBROSIANA/Getty Images

Sujit Sivasundaram asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780007575541

Ebook Edition © August 2020 ISBN: 9780007575558

Version: 2020-07-13

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

A Note on Transliteration and Images

List of Images

Timeline

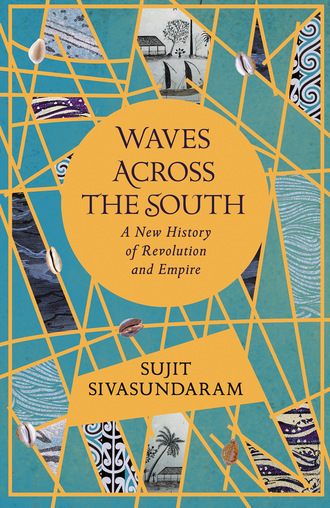

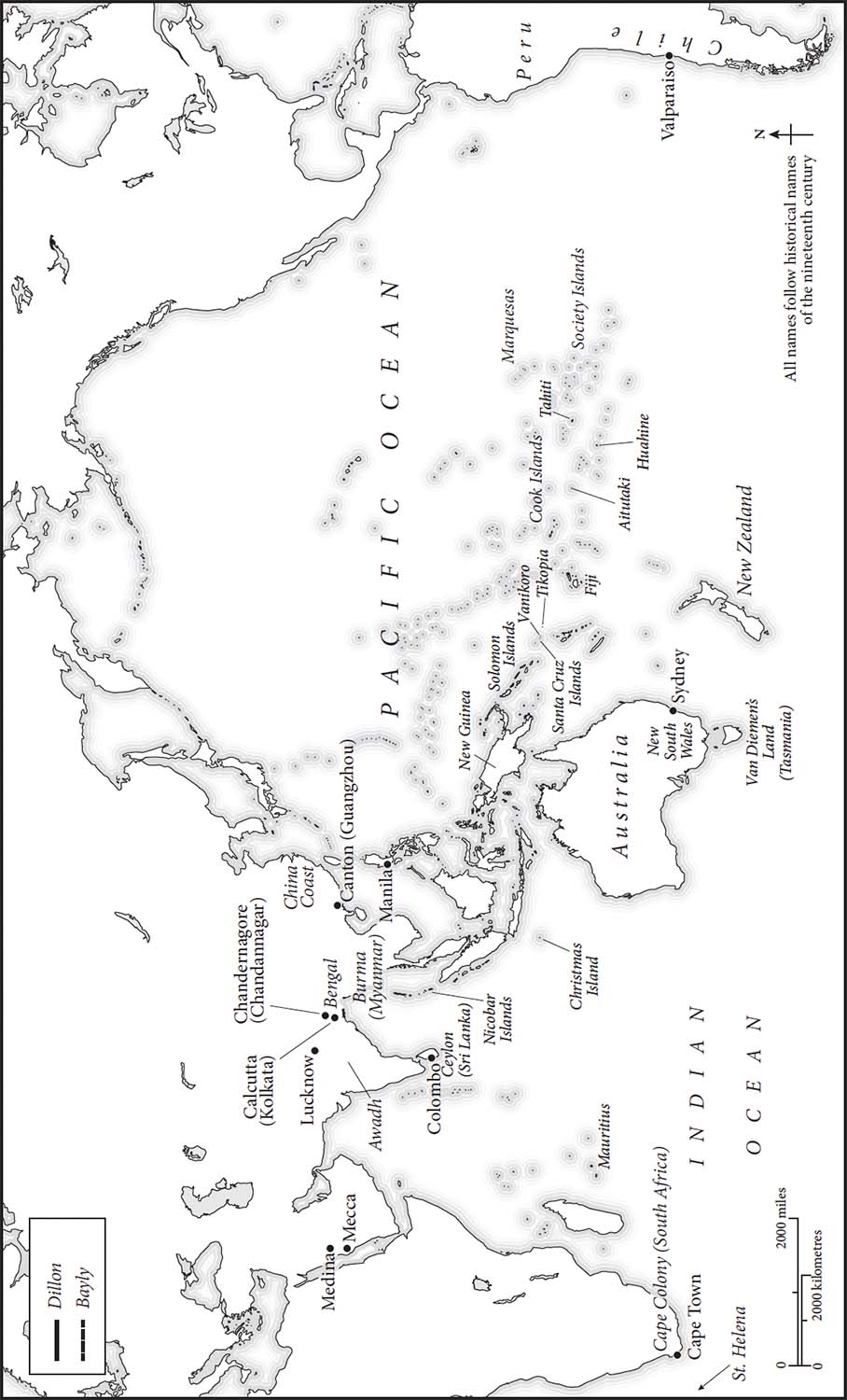

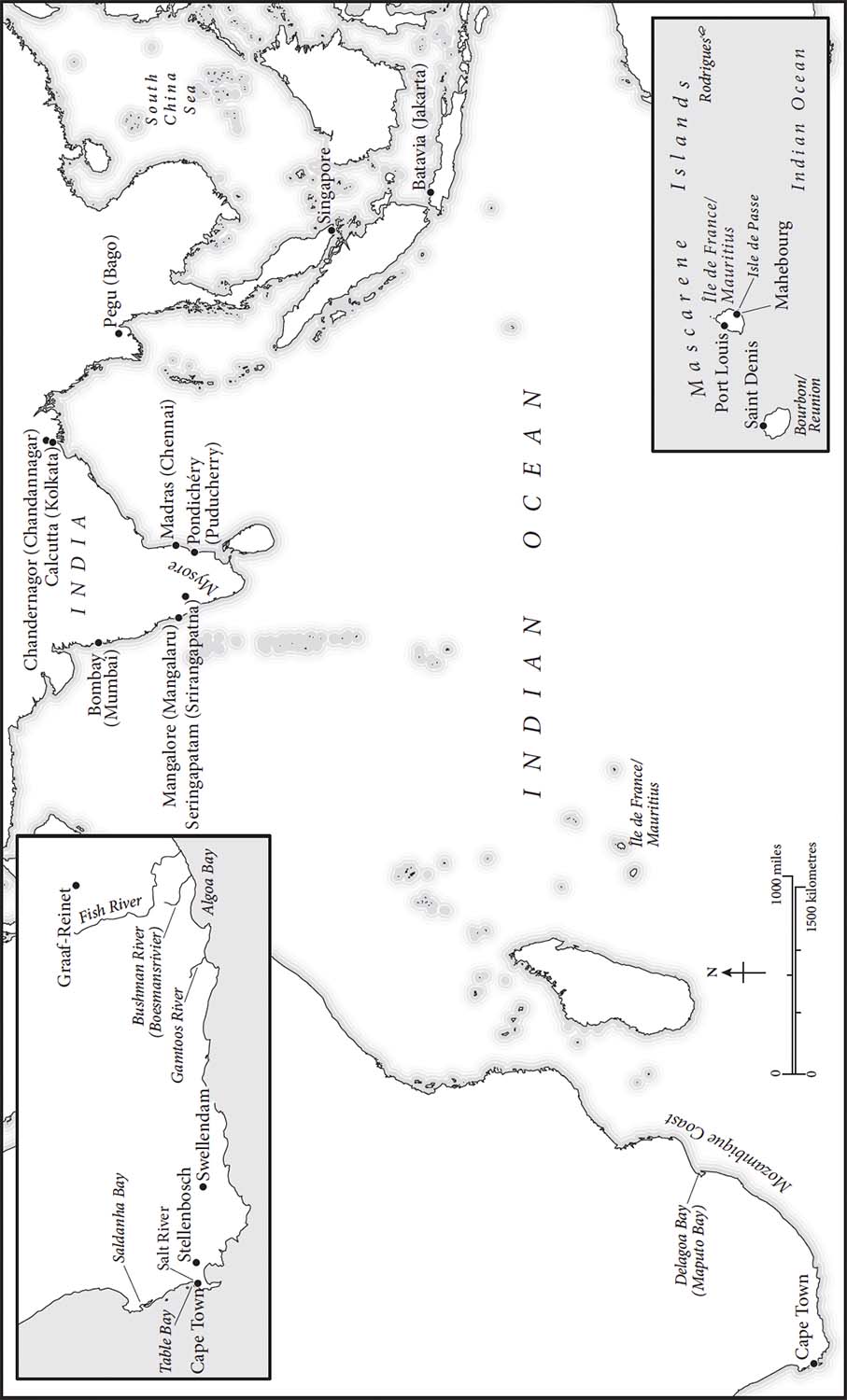

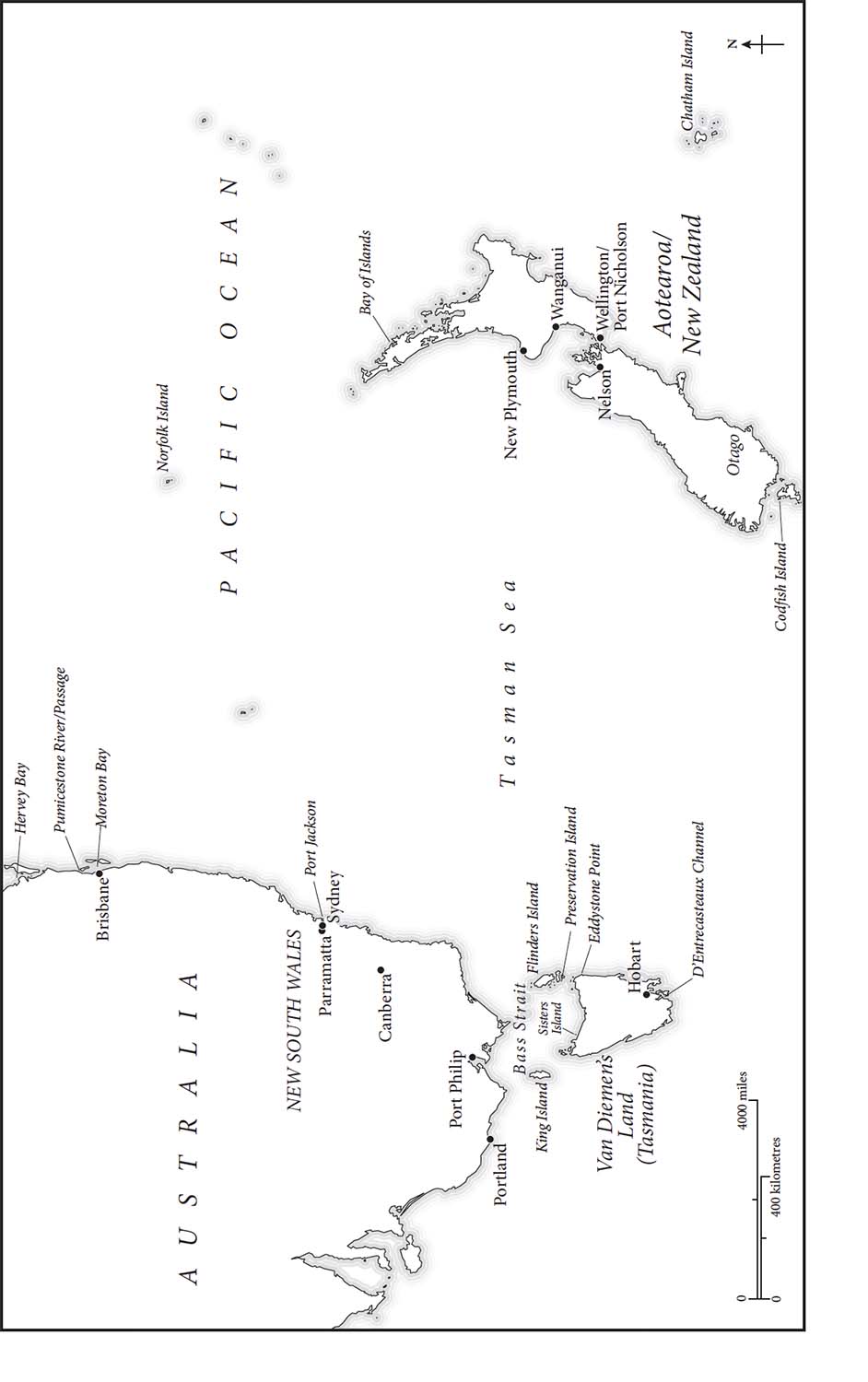

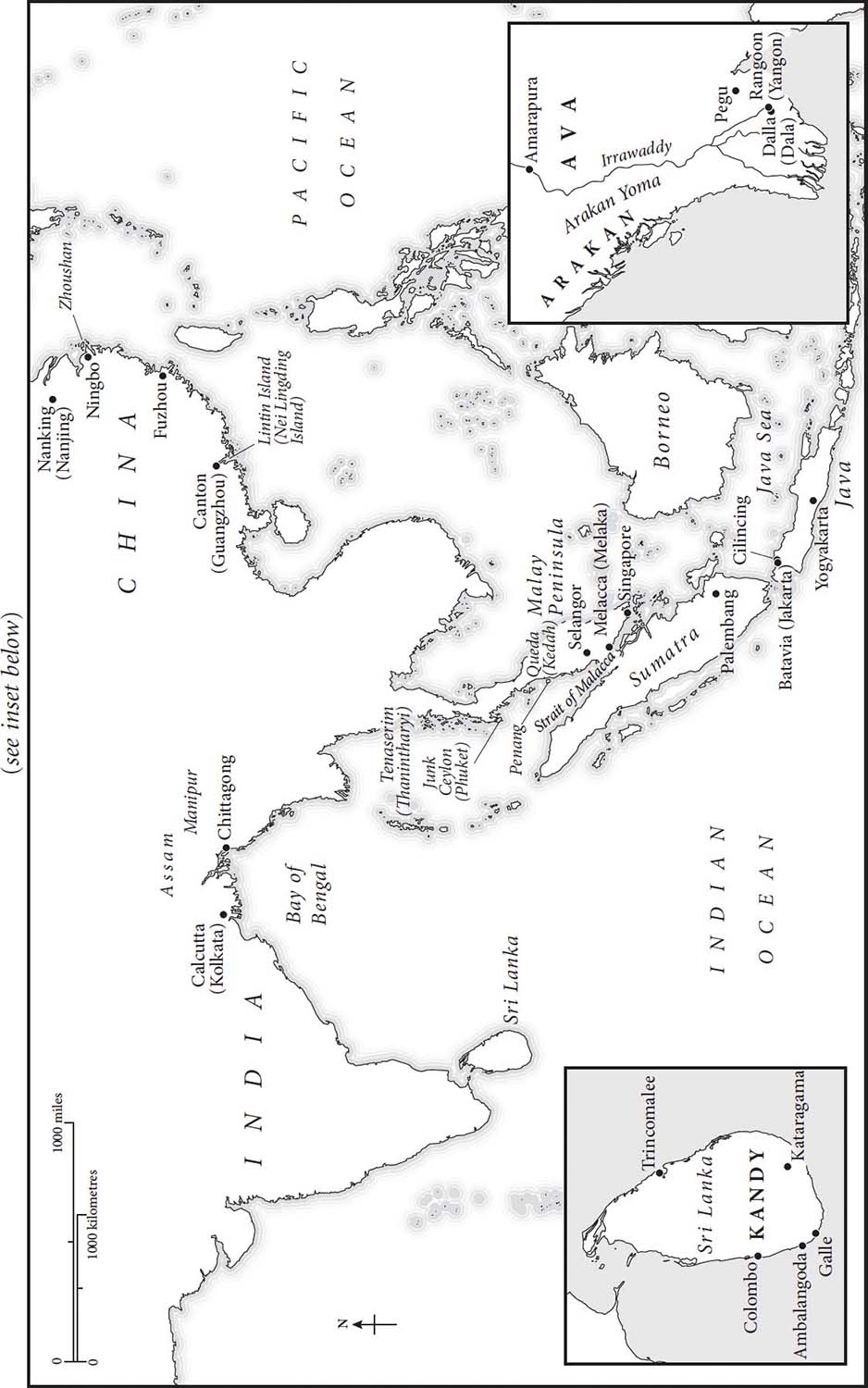

Maps

Introduction

1 Travels in the Oceanic South

2 In the South Pacific: Travellers, Monarchs and Empires

3 In the Southwest Indian Ocean: Worlds of Revolt and the Rise of Britain

4 In the Persian Gulf: Tangled Empires, States and Mariners

5 In the Tasman Sea: The Intimate Markers of a Counter-Revolution

6 At India’s Maritime Frontier: Waterborne Lineages of War

7 In the Bay of Bengal: Modelling Empire, Globe and Self

8 Across the Indian Ocean: Comparative Glances in the South

Conclusion

Afterword

References

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Publisher

A Note on Transliteration and Images

This is a work of world history that spans a wide terrain of culture and I have done my best to highlight indigenous and non-European names, given the intent of the work to consider the age of revolutions from the oceanic South. When a colonial name is used for the first time, the equivalent vernacular or indigenous term is highlighted in square brackets. I aim to move between indigenous, colonial and post-colonial names as I move across historical periods. Diacritics, ‘okina and other marks have been used where possible.

The images used in this book form a central part of the argument; many of them are colonial images. Some of these depict colonial invasion. Other images are of Indigenous peoples who have been racialised and gendered. They have been included here to destabilise and expose the colonial vision that gave rise to them and to make space instead for Indigenous peoples and their perspectives in the history of the age of revolutions.

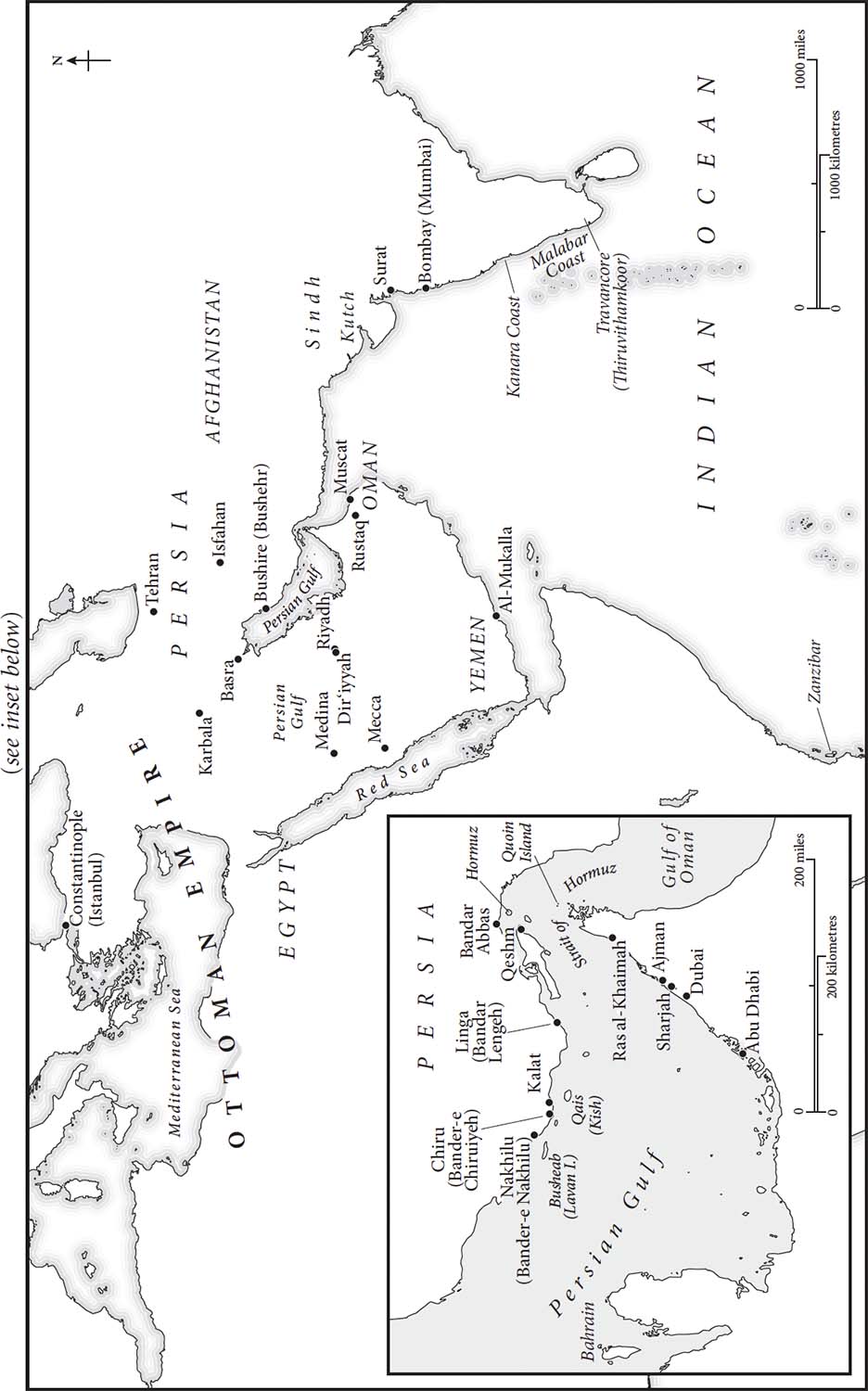

The beautiful cover for Waves Across the South was inspired by the maps used by Pacific islanders, to find their way across the vast expanse of the Pacific. These long voyages are discussed in the introduction. These maps consisted of various natural materials including coconut fronds and shells, denoting, for instance, the position of islands or currents. It is an appropriate cover for a book which considers world history from a ‘sea of islands’ in the global South. Each of these seas found its place within the rise and fall of the waves which indigenous navigators moved across.

List of Images

Introduction

0.1 ‘Fishing Boats in the Monsoon, northern part of Bombay harbour’ [Mumbai] (1826), from Victoria and Albert Museum, IS:4: 18-1955.

0.2 ‘Surf boat landing European passengers at Madras [Chennai]’ from National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, PAD1842.

0.3 ‘Landing [Waler] horses from Australia; Catamarans and Masoolah boat’, Madras, c.1834, the Mitchell Library, Sydney, Australia, DG SV*/Hors/1(a–b).

0.4 ‘Catamaran on Madras [Chennai] Roads’, by Augustus Earle, copy from National Library Canberra, PIC: Solander Box A40, NK 12/126.

0.5 ‘Tuki’s map’, National Archives, Kew, MPG1/532.

0.6 Bugis nautical map, 1816, [1231], Universiteitsbibliotheek Utrecht, KAART: VIII.C.a.2 (Dk 39-8).

Chapter Two

2.1 ‘Sauvages des îles de l’Amirauté’, Jacques-Louis Copia after Piron, reproduced in La Billardière’s Atlas (Plate 3), British Library.

2.2 ‘European ships as depicted on a Tongan clapping stick’ from the Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen (RV-34-6), likely to have been modelled on either the voyage of La Pérouse or the voyage of d’Entrecasteaux.

2.3 A fragment of sisi fale, ‘Coconut fibre waist garment, in all likelihood collected during the voyage of d’Entrecasteaux’ from the Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, 71.1930.54.153.D.

2.4 George I of Tonga (1880s) in his eighties; photographed by James Edge-Partington, British Museum, Oc, A58.2.

2.5 ‘Mr. Mariner in the Costume of the Tonga Islands’ (1817), was used as frontispiece in a book edited by John Martin, An Account of the Natives of the Tonga Islands, in the South Pacific Ocean: With an Original Grammar and Vocabulary of their Language (London: John Murray, 1816).

2.6 Port au Prince Memorial, Tonga and the beach where the massacre is alleged to have happened. Author’s photographs.

2.7 ‘Tepoanah Bay of Islands New Zealand a Church Missionary Establishment’ (watercolour, Augustus Earle, 1827), National Library of Australia, Canberra, NK 12/139.

2.8 ‘War speech’ by Augustus Earle (published 1838); Earle wrote of a ‘council for war’, ‘a rude parliament’, National Library of Australia, Canberra, PIC vol. 532 U2650 NK 668.

2.9 ‘King George. N. Zealand Costume’ by Augustus Earle (1828), National Library of Australia, Canberra, PIC Solander Box A37 T122 NK 12/84.

2.10 ‘The wounded chief Honghi [Hongi Hika] & his family’ by Augustus Earle (London: Lithographed and Published by R. Martin, 1838), National Library of Australia, PIC vol. 532 U2643 NK 668.

2.11 ‘Waikato, Hongi Hika and Thomas Kendall’ by James Barry, 1820, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, G/618.

Chapter Three

3.1 A later image of a man with mixed ancestry with a racialised title, published in an account of the French voyage of Nicolas Baudin. ‘Afrique Australe: Bastaard-Hottentot, ou Hottentot métis, revetu de ses habits de peau de mouton’ [Bastard Hottentot or mixed blood Hottentot, wearing his sheepskin clothes], in Voyage de Découvertes aux Terres Australes [Voyage of Discovery to the Southern Lands], (Paris: Arthur Bertrand, 1824), 2nd edn, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2010.96.56.

3.2 ‘A View of Table Mountain and Cape Town, at the Cape of Good Hope’, 1787, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, PAH2821.

3.3 ‘Bush Men Hottentots Armed for an Expedition’, in Samuel Daniell, A Collection of Plates Illustrative of African Scenery and Animals (London, 1804), British Library, 458.h.14, part 1.2.

3.4–5 Bo-Kaap in Cape Town, formerly known as the Malay Quarter, showing coloured housing, and where Awwal Mosque, shown below, was built in 1798. Author’s photographs.

3.6 Tipu Sultan of Mysore, a half-length portrait, c.1792, most likely by an unknown Indian artist, British Library.

3.7 ‘Isle of France, No.1: View from the Deck of the Upton Castle Transport, of the British Army Landing’, 1813, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, PW4779.

3.8 ‘Isle of France, No.5: The Town, Harbour, and Country, Eastward of Port Louis’, 1813, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, PW4783.

Chapter Four

4.1 ‘The Troops Landing at Rus ul Kyma [Ras al-Khymah] in I. Clark, W. William Haines and R. Temple, ‘Sixteen Views of Places in the Persian Gulph’, National Maritime Museum, PAF4799.

4.2 ‘The Storming of a Large Storehouse near Rus ul Kyma [Ras al-Khymah]’ in I. Clark et al., ‘Sixteen Views’, National Maritime Museum, PAF4800.

4.3 ‘Rus ul Kyma [Ras al-Khymah] from the S.W. and the Situation of the Troops’ in I. Clark et al. ‘Sixteen Views’, National Maritime Museum, PAF4801.

4.4 ‘Jamsetjee Bomanjee Wadia [Jamshedji Bamanji Wadia] (c.1754-1821)’, by J. Dorman, oil on canvas, c.1830, National Maritime Museum, BHC2803.

4.5 ‘Nourojee Jamsetjee [Naoroji Jamshedji] (1756–1821)’, by an unidentified artist, likely J. Dorman, c.1830, British Library.

Chapter Five

5.1 ‘Cora Gooseberry, Freeman Bungaree, Queen of Sydney & Botany’, brass breastplate, Mitchell Library, Sydney, R251B.

5.2 ‘Natives of New South Wales’ (undated, thought to be pre-1806), attributed to George Charles Jenner and William Waterhouse, the Mitchell Library, Sydney, Australia, DGB 10.

5.3 ‘Portrait of Bungaree, a native of New South Wales, with Fort Macquarie, Sydney Harbour in background’ by Augustus Earle, c.1826, The Art Archive.

5.4 ‘Bungaree, a native of New South Wales’ in Augustus Earle, Views in New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land: Australian Scrapbook (London: J. Cross, 1830).

5.5 ‘The annual meeting of the native tribes of Parramatta’ by Augustus Earle, watercolour thought to depict 1826 meeting, National Library of Australia, Canberra, PIC Solander Box A35 T95 NK 12/57.

5.6 W. H. Fernyhough, A Series of Twelve Profile Portraits of Aborigines of New South Wales, Drawn from Life (Sydney: J. G. Austin, 1836). These lithographs are of Cora.

5.7 Elephant seals at King Island off Tasmania. Victor Pillement, ‘Nouvelle-Hollande, Île King, l’elephant-marin ou phoque à trimpe, vue de la Baie des Elephants’ (Paris: Arthur Bertrand, 1824), National Library of Australia, PIC vol. 599, PIC/11195/62 NK 1429.

5.8 Papers of George Augustus Robinson, vol. 8, part 2, Van Diemen’s Land, 30 September–30 October 1830’, Mitchell Library, Sydney: A7029, part 2.

Chapter Six

6.1 ‘One of the Birman Gilt War Boats Captured by Capt. Chads, R.N. in his successful expedition against Tanthabeen Stockade’, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, PAG9121.

6.2 Parabaik image, showing royal festival on water, British Library, Or 16761, f. 28r.

6.3 ‘The Conflagration at Dalla’, from Joseph Moore, Rangoon Views and Combined Operations in the Birman Empire, 2 vols (London: Thomas Clay, 1825-6), vol. 1, no. 17.

6.4 Shwedagon Pagoda, Author’s photograph.

6.5 ‘Sketch of Napoleon Bonaparte after his death at St Helena’, by Captain Frederick Marryat, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, F4154.

6.6 ‘The late King of Kandy from a drawing by a Native’, in John Davy, An Account of the Interior of Ceylon and of Its Inhabitants with Travels in that Island (London, 1821).

Chapter Seven

7.1 Length of Pendulum Experiment at Madras, in J. Goldingham, Madras Observatory Papers (1827).

7.2 ‘View of the Island of Gaunsah Lout [Gangsa Laut] with the Observatory and Encampments’, from John Goldingham, Report of the Length of the Pendulum at the Equator … Made on an Expedition … from the Observatory at Madras [Chennai](Madras, 1824), figure 11, at Royal Society, RS.10694.

7.3 ‘Plan of the Island of Gaunsah Lout on which the Experiments for ascertaining the Length of the Pendulum were made’, from Goldingham, Report of the Length of the Pendulum, figure 10, at Royal Society, RS.10693.

7.4 Horsburgh Lighthouse today, File 9/21, October 2012, from www.lightphotos.net.

7.5 J. T. Thomson, Chinese Stonecutters, 1851, from Thomson’s sketchbook, University of Otago Heritage Collections, 92/1239.

7.6 Waterspouts off Barbukit Point, 1851, from Thomson’s sketchbook, University of Otago Heritage Collections, 92/1217.

Chapter Eight

8.1 ‘Vue de la ville du Port Napoleon prise de la Montagne du Pouce’, from J.G. Milbert, Illustrations de Voyage pittoresque à l’Île de France (Paris: Nepveu, 1812), Bibliothèque nationale de France.

8.2 Thomas Bowler, ‘Cape Town and Table Mountain from Table Bay’.

Maps

Introduction

There is a quarter of this planet which is often forgotten in the histories that are told in the West. This quarter is an oceanic one, pulsating with winds and waves, tides and coastlines, and islands and beaches. The Indian and Pacific Oceans – taken as a collection of smaller seas, gulfs and bays – constitute that forgotten quarter, brought together here for perhaps the first time in a sustained work of history. These watery spaces of the south, studded with small strips of land, facing gigantic landmasses, occupy centre stage in what follows. They are cast as the makers of world history and the modern condition.[1]

The decades straddling the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, which historians call the ‘age of revolutions’, traditionally encompass an Atlantic triangle of grand events. This triangle of events includes the American Revolution, the French Revolution and revolts in the Caribbean, such as the Haitian Revolution, and then independence movements in Latin America in the early nineteenth century.[2] Many things changed dramatically in the midst of these revolutions and the wars that accompanied them. Among what was made anew are the organisation of politics, the conception of equality and rights; the mechanics of governance and empire; the status of labour and enslaved people; the workings of technology, industry and science; and characterisations of nation and self as well as public consciousness. By looking to the forgotten quarter of the Indian and Pacific Oceans, the intent is to turn the story of the dawn of our times inside out. It is to insist on the critical significance of the peoples and places in this oceanic tract in shaping the age of revolutions and so our present; and, accordingly, the need to meditate on this part of the world in considering the human future.

The age of revolutions is one of the most long-lasting labels of historical writing. It was used in the period and has carried on being used to describe the set of decades at the end of the eighteenth and the start of the nineteenth centuries. To look at this historical period again with a focus on the Indian and Pacific Oceans challenges the dominance of the West and Europe in the history we remember. This is especially important when what is at stake in descriptions of an age of revolutions is the lineage of our very rights and selfhood, and the memory of the contests and standoffs that gave rise to the world we inhabit. Approaching the past like this displaces the pernicious assumption that the soul of the world was crafted in the West and then travelled east; it rejects the notion that political subjectivity was forged in the Atlantic and that people elsewhere followed in the same tracks. The objectionable sentiment was phrased like this by one important early historian of the age of revolutions, R. R. Palmer: ‘[a]ll revolutions since 1800, in Europe, Latin America, Asia and Africa, have learned from the eighteenth-century Revolution of Western Civilisation.’[3] The history that follows refuses to cast Western and Atlantic Civilisation in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries as the font of revolutionary sentiment. Nor was the West or the Atlantic the single origin of the modes of economic, technological, military and cultural expression that accompanied revolution.[4]

When the age of revolutions is reconceptualised from the oceanic south, an uncertain and violent tussle appears. Within the Indian and Pacific Oceans there was a contest between revolution and an imperial system which perverted the course of revolution and constituted a counter-revolution. Neither one of the forces of revolution and empire wiped the other out, but the balance shifted as the British empire in particular became the chief victor over these seas by the middle of the nineteenth century. While there were certainly other ideological, cultural and political impulses which drove the nineteenth-century British empire, one intent of this work is to track its origins as a counter-revolution.[5] The manner in which this empire suppressed the many possibilities of this time points to sinister imperial manoeuvring in the global South.

In these two oceans, the age of revolutions should be seen first and foremost as a surge of indigenous and non-European politics which met the invaders and colonists who washed ashore. In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the inhabitants of the Indian and Pacific Oceans adopted and at times forcibly took from outsiders new objects, ideas, information and forms of organisation, all of which were used for their own purposes. One might think here of notions of monarchy, weapons, political association, science and medicine, and debate in the press. Oceanic peoples also recalibrated existent traditions and beliefs, modes of governance and war and relations with neighbours, in order to meet these new times. Here one might bring to mind Islamic or Buddhist reform or the changes in established long-distance relations for migration and trade. All this constituted the Indian and Pacific Oceans’ age of revolutions. As a term of description, ‘indigenous’ has to be defined expansively in these seas. For oceanic peoples were often on the move and may be better described as diasporas than indigenous populations; they had complex cultural heritages. Settlers and indigenous peoples could also at times borrow from each other, making it difficult to draw a clear distinction between who and what was indigenous and who and what fell outside the category.

A sequence of voices across the sea embody an energetic indigenousness: Pacific Islander, Māori, Aboriginal Australian, Arab, Qasimi, Omani, Parsi, Javanese, Burmese, Chinese, Indian, Sinhalese, Tamil, Malay, Mauritian, Malagasy and Khoisan perspectives come into view below.[6] These and other peoples took passage as sailors, partners, fighters, labourers and travellers in these decades of unprecedented globalisation. Indeed, the most enjoyable part of researching this book was discovering links across the water through regions and territories that have not been cast together.

In addition to a surge of indigenous and non-European politics, the age of revolutions in these oceans saw a reconfiguration of political organisation. Empires, political units, kingdoms and chieftaincies were realigned or reorganised from Oman to Tonga and from Mauritius to Sri Lanka. Political tussles over water were poised such that relatively new forces could find their own way, acting as independent states or reacting to a colonial definition of what could count as a state. Venerable Eurasian empires, Ottoman, Mughal and Qing, were transformed at their maritime frontiers. New political formations, including monarchies inaugurated in the Pacific, could also cohere through the adoption of the maritime and military techniques of warring Europeans. Refugees of the Napoleonic wars could serve as advisers, for instance in Burma [Myanmar] to the kingdom of Ava as it fought Britain, or in Tasmania to a heavily militarised British colonial state. Oceanic peoples, including Asian sailors called lascars at the time, could establish a political pathway within the British empire’s need for allies and collaborators without finding full meaning within empire. Those who took passage on European ships, or who worked on grand projects as labourers and technicians, could use this moment of opportunity to contemplate their selfhood and futures in radically new ways.

The British empire sought to neutralise or adopt the ideas, people, structures and modes of organisation which arose from the age of revolutions. It moved from sea to land and saw itself as an empire for liberty in sites as different as Singapore and Mauritius. In addition to seeing itself as spreading liberty, there were many ways in which the British empire acted in reactionary fashion in the age of revolutions. There was a lineage of wars over water across the first half of the nineteenth century, all of which employed the period’s characteristic ‘total war’, including looting and wide-scale bloodshed.[7] In the Bay of Bengal, for instance, these wars drew military men and techniques from the revolutionary and Napoleonic wars linking them to the global warfare of this moment. Britain’s invasive missions to the Gulf in 1809–10 and 1819–20 stood against a brand of Islamic reform which was compared with revolutionary sentiment elsewhere. The British fear of republicanism motivated invasions in Java and Mauritius in 1810–11. In all of these cases, British colonial and maritime war in these years was forged out of the age of revolutions in relation to tactics, ideology, motivation and forms of comparison.