Waves Across the South

Fig. 2.1 ‘Sauvages des îles de l’Amirauté’, Jacques-Louis Copia after Piron, reproduced in La Billardière’s Atlas, 1800

2.1 © Pictures from History / Bridgeman Images

In the forty years of uncertainty that followed the disappearance, the fate of La Pérouse led to much speculation across Europe, inspiring plays, pantomimes and books, some with far-fetched romantic plot-lines.[27] The solution eventually came from Peter Dillon and through his meeting with Joe, the lascar in 1826. In a book published to cement his fame as the problem solver and to add to his pocket, Dillon provided this account of an interview with islanders on Vanikoro in late 1827:

Q. ‘How were the ships lost?’ – A. ‘The island is surrounded by reefs at a distance off shore. They got on the rocks at night, and one ship grounded at Wannow, and immediately went to the bottom.’

Q. ‘Were none of the people from the ship saved?’ – A. ‘Those that escaped from the wreck were landed at Wannow, where they were killed by the natives. Several also were devoured by the sharks, while swimming from the ship.’

Q. ‘How many people were killed at Wannow?’ – A. ‘Two at Wannow, two at Amma and two more near to Paiow. These were all the white men who were killed.’

Q. ‘If there were only six white men killed on shore, how, or from whence, came the sixty sculls [sic.] that were in the spirit house at Wannow, as described by Ta Fow, the hump-backed Tucopian, and others?’ – A. ‘These were the heads of people killed by the sharks.’

…

Q. ‘How was the ship lost near Paiow?’ – A. ‘She got on the reef at night, and afterwards drifted over it into a good place. She did not immediately break, for the people had time to remove things from her, with which they built a two-masted ship.’

…

Q. ‘Had these people no friends among the natives.’ – A. ‘No. They were ship spirits; their noses were two hands long before their faces. Their chief used always to be looking at the sun and stars, and beckoning to them. There was one of them who stood as a watch at their fence, with a bar of iron in his hand, which he used to turn round his head. This man stood only upon one leg.’[28]

So what is the headline? La Pérouse’s ships had come to their end in the midst of a hurricane. Though some of the crew remained, most of them sailed away in a small vessel they built never to be seen again. Evidently, before they left, their astronomical interests and their manners had bewildered the inhabitants of Vanikoro.

If the tragic ends of the expeditions of La Pérouse and d’Entrecasteaux are in keeping with the age of revolutions, the third French expedition, commanded by Nicolas Baudin and commissioned by Napoleon in 1800 at a different political moment, was relatively more successful. Baudin had sailed widely across the Indian and Pacific Oceans as a merchant captain. He focussed on precision rather than breadth and was instructed to concentrate on Australia. The need now was for voyages ‘restricted to specific pre-determined, points, directed to the least-known coastlines’.[29] However there were still squabbles on board which were typical of the broader character of this period. The commoner Baudin was seen as a social inferior by some of the scientists, and his first lieutenant even challenged him to a duel.[30] Social and ideological differences merged with scientific disputes: ‘sketchers’ and ‘anatomists’ on board, two classes of researchers, argued over the ownership of a dead porpoise; there was a similar fight about who got the right to dissect the first shark.[31]

Freycinet, who sailed with Baudin, published the first complete map of Australia in 1811. The credit for putting Australia in its place on a map belongs, however, to a Briton, Matthew Flinders. After securing British passports for the Baudin mission, the leading British man of science of this period, Joseph Banks, had the idea of a competing British mission. He arranged for Flinders to be sent off to chart south west Australia in a race with Baudin. Despite their common scientific interests, and the fact that Flinders had advised Baudin to stop in Port Jackson (the ria of what is now Sydney) when in need of refreshment, the impact of the revolutionary era dictated the outcomes for these two.

Before Baudin died from tuberculosis in Mauritius in September 1803, he wrote to the French Minister of Marine: ‘I have enough strength left at the moment to assure you that the intentions of the Government have been fulfilled and that this voyage will be honourable to the French.’[32] Flinders pulled into Mauritius in December 1803, just after the death of Baudin, in urgent need of supplies and took confidence from his French passport, which asked all French agents to give him protection as the commander of a purely scientific expedition. Yet Governor Decaen, who reined in Mauritius’ republicanism, took him captive for six and a half years, until the eve of the taking of Mauritius by the British in 1810. Flinders’ books and papers were initially impounded and Flinders was accused of being an imposter. The navigator wrote that his daily routine consisted of learning Latin, writing up his ship’s log, music and billiards; he was later transferred to a more relaxed residence on a plantation, where he worked at translations between English and French.[33] The British got wind of his captivity, via American traders who enjoyed a healthy commerce with Île de France in this period. Such traders allowed Flinders to keep up a regular correspondence home, while also sending scientific materials through them to London, including to Banks.[34] Flinders’ health deteriorated while in captivity and though he returned to Britain, he did not live to see the publication of the account of his voyage.[35]

The French Revolution and its aftermath did not simply disrupt the passage of French and British voyages of exploration in the Pacific. The politics of the era certainly changed the nature and goals of voyaging. Gentlemanly culture still dominated British voyaging, but changing social orders were evident in the commoner Baudin’s leadership of a French voyage, though aristocratic commanders did follow him. While scientific cords bound the missions of the French and the British together, the tensions of these years dictated that friendly assistance was no longer guaranteed, as is evident in the fate of the d’Entrecasteaux/d’Auribeau expedition. Even navigators – like Flinders – could become captives. As the British started to annex territory and build bases in the Pacific they used the tumult of the age to their benefit. The French had to find their own way to create an imperial presence, while coming to terms with their distinctive commitments to revolution and nation-building.[36]

Despite differences, these two national modes of engaging with the Pacific were interlinked too: not all Frenchmen were republicans after all, and neither were all Britons anti-French. Even Flinders wrote to his wife Ann: ‘I am not without friends even amongst French men. On the contrary, I have several, and but one enemy [Governor Decaen].’[37] It was a story of a dance of European cousins. The French and British were trying to tame the Pacific, mindful of their related but different goals.

THE MAKING OF PACIFIC MONARCHS

The age of revolutions is evident not simply on the decks of vessels traversing these vast swathes of water, coming to terms with the news from Europe and working out the local outcomes of that news. To keep the story to that would still be to make the Pacific a distant planet orbiting Europe. In the exchanges between voyagers and islanders in the age of revolutions is a surge of indigenous politics and the rise of a counter-revolutionary British empire. At the heart of such exchanges was an eclectic range of ideas, techniques and materials and all of this made it possible for old systems of rule by chiefs to evolve into more centralised systems of monarchy right across the Pacific. Tonga is a good place to track this. It was here while in search of La Pérouse that d’Entrecasteaux had some of his most charged ethnographic encounters.

James Cook left a long shadow over those voyagers who followed in his wake in the two decades after his dramatic death at the hands of alleged cannibals in Hawai‘i in 1779. D’Entrecasteaux referred to Cook’s observations throughout the course of his journal, and sought to fill any gaps left by a man immortalised for his mapping of the Pacific. Remarkably, European voyagers through the Pacific were already starting to leave their debris strewn across the islands as a mark of their passage through them. For the likes of d’Entrecasteaux, items of European trade, European clothing or even the remains of wrecked ships became symbols of those who had passed before: points of comfort as well as melancholic tokens of disaster. In Adventure Bay in Tasmania, d’Entrecasteaux saw signs of what he took to be ‘temporary British establishments’; and suspected that there were remains of ‘several wooden stands destined to hold instruments in place for astronomical or trigonometrical observations’. By deciphering inscriptions found on trees, he worked out that William Bligh, who had served with Cook and who would later govern New South Wales, and who is now remembered for the mutiny that overtook his own expedition on the Bounty in 1789, had left some plants in Adventure Bay. D’Entrecasteaux made a point of determining whether these trees had prospered, sending his gardener, who later turned into a rebel outside Surabaya, to inspect them. While some pomegranate trees, a quince tree and fig trees were found, they were not doing well: ‘A five-and-a-half foot apple tree was found on the east coast of Adventure Bay which must have been planted several years before Captain Bligh’s visit; it was struggling, and its chances were not very promising.’[38] Despite the tense intellectual competition between the French and British voyagers, the responses to the litter left by rivals across the landscape of the Pacific point to how these European cousins felt that they were following related paths across the sea.

In Tongatapu, the main island of what is now Tonga, there was the same French interest in whether British attempts at improvement had succeeded. While in Tongatapu from March to April 1793, d’Entrecasteaux reported that Cook’s and Bligh’s voyages were ‘perfectly recollected’ by Tongans, but that no account of La Pérouse was forthcoming even from ‘the most intelligent’ of them.[39] This was despite the fact that La Pérouse had made a brief stop in Tonga. Later investigators such as Peter Dillon and a French expedition under Dumont d’Urville were able to gather recollections in Tonga of the La Pérouse mission.[40] D’Entrecasteaux detected a large number of items of British manufacture but none of French manufacture. He quickly arranged for French medals to be given out, as if to rectify the imbalance and to test whether they brought La Pérouse to mind. When a feast was held in d’Entrecasteaux’s honour by a chief called Tupou, the navigator took a billy goat and a pregnant nanny goat along as a gift, as well as a pair of male and female rabbits. But d’Entrecasteaux regretted Tupou’s indifference in receiving them and turned the conversation to the cattle that Cook had left in Tonga. The sheepishness of the Tongans’ response indicated that something was amiss.[41] Was it that they worried that he would ask for the cattle as gifts? This was a minor particular for d’Entrecasteaux to devote such energy to while exploring the other side of the world. But towards the end of the mission’s time in Tonga, the royalist d’Auribeau (who later took over from d’Entrecasteaux) wished to solve the puzzle. He visited a chief, Fuanunuiava, whose father had received the cattle from Cook, only to discover ‘a kind of mausoleum, which [Fuanunuiava] offered to dig open, so that the bones of these animals could be recognized’.[42]

This nicely illustrates the keen competition between French and British voyagers over natural husbandry. Such competition was tied to a shared commitment between these rival explorers to the idea that agricultural improvement was central to the making of settled and progressive societies in the Pacific. As empire moved from sea to land, maritime missions like this set the terms for commercial exchange of crops and plants and also for further schemes of land-based control. It was not coincidental that European voyagers themselves required replenishment when they called at islands.

D’Entrecasteaux was troubled by the nature of authority on the island of Tongatapu. He wrote: ‘I believe, like Cook, that this government has a lot in common with the old feudal regime, where the inconveniences increase in proportion to the weaknesses of the principal chief.’[43] Tonga was seen to be in anarchy; what was needed was proper governance tied to the agricultural uplift of the land. For d’Entrecasteaux anarchy was evident in the prevalence of theft, which arose from the insecurity of property. The chiefs owned all the property and could demand from their inferiors anything that they wished. The chiefs’ privilege lay also in how they had the right to multiple wives. D’Entrecasteaux noted the appearance of these women in heavily patronising terms:

Most of the women of the class in which the chiefs belong have very good looks: their aspect is interesting; they are expressive, without being flirtatious. They usually have beautiful hands, and their fingers could easily be used as models.[44]

Yet d’Entrecasteaux was plagued by the riddle of identifying the monarch of Tongatapu. Between Cook’s visit and his own, he would have expected that the throne would have passed to Fuanunuiava, the son of the man denoted as sovereign by Cook.[45] Perhaps it was because of Fuanunuiava’s youth, he pondered, that this had not occurred. D’Entrecasteaux also puzzled over the fact that Queen Tiné, whom he now took to be the head of state, could not confer the throne on her death to her immediate relations. For d’Entrecasteaux the complicated rules of succession were part of the problem. There was too much confusion in ‘distinguishing men who exercise power and to whom respect is given’.[46] D’Entrecasteaux was a man who wished for authority, but for the kind of authority held up by rules and constitutions and hemmed in by a market in trade and land and also by familiar gender norms. D’Entrecasteaux’s naturalist de La Billardière, later one of the leaders of the republican faction, wrote meanwhile of ‘King Tuoobou’ or Tupou of Tonga.[47] Tupou was in fact the Tu‘i Kanokupolu, one of three paramount titles in Tonga; the highest ranking however held another title, Tu‘i Tonga. Fuanunuiava was named as Tu‘i Tonga in 1795. La Billardière also observed how Queen Tiné was conscious of her privileges as the paramount authority on Tonga. Lower ranking chiefs including Tupou were obliged to pay their respects by taking her right foot to their heads.[48]

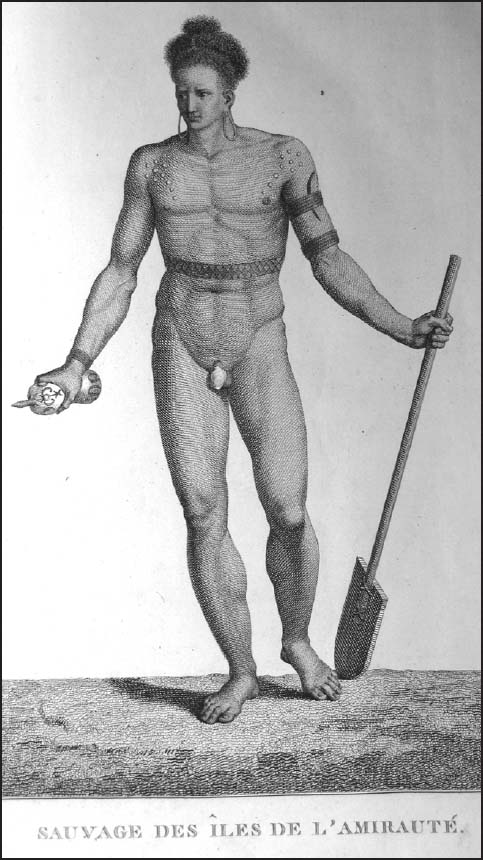

D’Entrecasteaux’s portrait of Tonga reveals more of himself than the Tonga of this period. Despite how the terms of King and Queen pepper so many European reports of the Pacific, in this era, until the arrival of Europeans, there were no European-style kings and queens. In Tongatapu, the status of chiefs was determined on the basis of descent from a chosen ancestor, where age and gender were important as in Europe; but in Tonga sisterhood was ranked as a higher privilege than brotherhood in determining succession.[49] The differences between chiefs and others did not lie in the labour they undertook, if any, and so the language of class that d’Entrecasteaux used to observe Tonga was misplaced. Objects were not sold and did not retain a value on the basis of the work that had been put into making them. Rather value was determined primarily by the rank and status of the creator of the object: it was no wonder that Tongans wished to possess European objects. Yet those whom the Tongans called papalangi, or men from the sky, introduced into these islands a new language of politics, class and organisation. It was through a European insistence on the value of labour, the market and industry, together with a supplanted language of kingship, that political change was ushered in. Such change was consistent with the broader political transformations across the world in this age. In this region, these changes counted as a firming up of monarchy whereas elsewhere it could see monarchies torn down. Items like d’Entrecasteaux’s medals – and European weapons in particular – fed into the intense wars and political instability in early-nineteenth-century Tonga. Chiefs quarrelled over the arrival of European ships, trying to attract them to their harbours. [Fig. 2.2] And those who resided at ports inevitably did better than those based elsewhere. As Europeans sought for kings and queens, islanders reinvented their politics.

Fig. 2.2 ‘European ships as depicted on a Tongan clapping stick’

2.2 © Collection Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen. Coll.no. RV-34-6

Sexual favours also became part of this market and a means of establishing strategic friendship with Europeans. La Billardière’s account of the d’Entrecasteaux expedition includes an image titled ‘Dance of the Friendly Islands in the Presence of the Queen Tiné’, showing bare-breasted women draped from their waists down in what is probably bark cloth. D’Entrecasteaux entertained Tiné with the music of a violin and cittern and she returned the favour, instructing Tongan women to sing of the great deeds of warriors. Some of the younger women wear girdles around their waists, probably sisi fale, worn by high-born women in dances in honour of the Tu‘i Tonga.[50] [Fig. 2.3] Yet Tiné desired to firm up her relationship with the commander. She invited him to reside in her house: ‘the Admiral had no opportunity of appreciating justly the motive for these obliging offers, for he did not accept her invitation.’[51] This report of Tiné’s invitation to d’Entrecasteaux was in keeping with how ‘Queen Oberea’ was alleged to have greeted Cook’s voyage and had sex with Joseph Banks, the gentlemanly naturalist, who later went on to organise papers for Baudin.[52] When the reports of Cook’s journey went to press, this supposed queen of Tahiti became an emblem of the exotic in Europe. As she slept with Banks, she was seen to have given her kingdom to her lover. Despite the differences between Europe and Polynesia, between monarchic and chiefly systems of rule, sex crystallised powerful unions.

Fig. 2.3 A fragment of sisi fale, ‘Coconut fibre waist garment, in all likelihood collected during the voyage of d’Entrecasteaux’

2.3 © Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais

In an age of revolutions that saw active debate about the nature of politics and about monarchies and republics, it is striking to see how indigenous peoples created centralised Pacific kingdoms. Pacific islanders participated in and crafted the age of revolutions too, a point which historians have struggled to see. These new monarchies made identifiable representatives of island societies, who could serve as the point of focus for collaboration with British and other foreign agents as well as resistance against invading imperialists. In Tonga, at the same time as the arrival of a range of European settlers in the 1790s, including traders, evangelical missionaries as well as those who had escaped from the convict settlement in Australia, there came a long civil war between rival chiefs. The investiture of the paramount chief, Tu‘i Tonga, was laid aside and there was a conflict between the lineages of the Tu‘i Tonga and Tu‘i Kanokupolu.[53] Chiefs fought over tribute and connections to missionaries and other Europeans. The wars between chiefs were attended by the spread of European diseases and weapons, and the fleeing of many chiefs to neighbouring Fiji or Samoa. One chief fled with his wife to British Sydney.[54] In the midst of these radical changes, there was a loss of cohesion and the chiefly system of rule was in crisis.

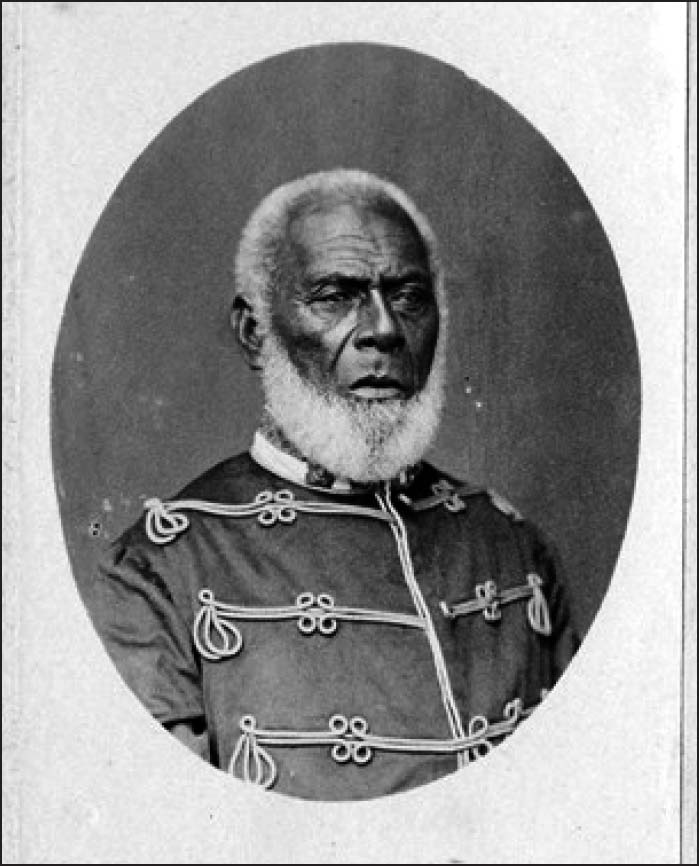

If Pacific notions of monarchy drew from contact with Europeans in political and material terms, religion also played a vital role in the new order of politics that then arose in a place like Tonga. The work of Protestant missionaries is notable here. A new age dawned in Tonga with the conversion of the uninstalled paramount chief Taufa’ahau to Protestantism through the work of Wesleyan missionaries who arrived in 1822. This man changed the political make-up of Tonga and transformed it from a competitive set of chiefdoms to a united monarchic polity. Taufa’ahau took the name George I at his baptism in 1831 and used the support of British missionaries to unify Tonga. The change in religion signified a drastic change in political organisation: for where chiefs had received their sanction from lineages tied to gods, the spread of Christianity now brought a different relationship between political and sacred authority. Now the missionaries were the purveyors of the Word, and George I was the keeper of the law. Taufa’ahau’s opponents feared that soon the missionaries themselves would become chiefs. Many of George I’s followers adopted Christianity, though there continued to be a great deal of wavering and movement in and out of Christian faith and church attendance. George I boasted: ‘I am the only Chief on the Island … When I turn they will all turn.’[55] He was right: George I’s monarchic line has survived till today, priding itself on never being formally colonised. [Fig. 2.4]. Tonga is a microcosm of changes which were afoot across the wide expanse of the Pacific.

Fig. 2.4 George I of Tonga (1880s) in his eighties

2.4 © The Trustees of the British Museum

In Tahiti, where Banks had apparently slept with his lover, the queen, Cook used the vocabulary of royalty in ordering his observations. In contrast with d’Entrecasteaux’s comments on Tonga, Cook noted that Tahiti’s was a benevolent monarchy. All had free access to King Tu in Tahiti: ‘I have observed that the chiefs of these islands are more beloved by the bulk of the people, than feared. May we not conclude from hence that the government is mild and equitable?’[56] By the time that Bligh arrived the Tahitians knew the line themselves: the Pomare family had established a kingly lineage. Pomare II invited Bligh to a ceremony allegedly involving human sacrifice, where the victims were the violators of some tabu (taboo). The ceremony ended with a prayer for the British monarch. When Bligh celebrated the birthday of the British monarch, George III, with fireworks, free alcohol and a twenty-one-gun salute, the alliance of monarchs was complete. European weapons were central to the consolidation of this monarchic line.[57] Further to the east in Hawai‘i, a dynasty was founded by Kamehameha, who was also visited by Cook and other European navigators. By the 1820s, the monarchy of Hawai‘i could be idealised as perfect for a post-revolutionary world. As the Russian commander Otto von Kotzebue explained in arriving in Hawai‘i, Kamehameha had got the right balance between tradition and change. He was already preparing for succession.

The intertwined changes in politics between Europe and the Pacific in the age of revolutions run across commitments to monarchy, agriculture, land, gender and sex. These changes seem unexpected because the Pacific is so far away from Europe. How did they become possible in practical terms? The entanglement of Europe and the Pacific might be described through the image of raiding. Islanders raided Europe for everything that came on their ships, from political ideas to animals and plants, and used them for their own purposes in the light of the old.