полная версия

полная версияThe American Revolution

When the force of minute-men, watching events from the hill beyond the river, had become increased to more than 400, they suddenly advanced upon the North Bridge, which was held by 200 regulars. After receiving and returning the British fire, the militia, led by Major Buttrick, charged across the narrow bridge, overcame the regulars by dint of weight and numbers, and drove them back past the Old Manse into the village. They did not follow up the attack, but rested on their arms, wondering, perhaps, at what they had already accomplished, while their numbers were from moment to moment increased by the minute-men from neighbouring villages. A little before noon, though none of the objects of the expedition had been accomplished, Colonel Smith began to realize the danger of his position, and started on his retreat to Boston. His men were in no mood for fight. They had marched eighteen miles, and had eaten little or nothing for fourteen hours. But now, while companies of militia hovered upon both their flanks, every clump of trees and every bit of rising ground by the roadside gave shelter to hostile yeomen, whose aim was true and deadly. Straggling combats ensued from time to time, and the retreating British left nothing undone which brave men could do; but the incessant, galling fire at length threw them into hopeless confusion.

Retreating troops rescued by Lord PercyLeaving their wounded scattered along the road, they had already passed by the village green of Lexington in disorderly flight, when they were saved by Lord Percy, who had marched out over Boston Neck and through Cambridge to their assistance, with 1,200 men and two field-pieces. Forming his men in a hollow square, Percy inclosed the fugitives, who, in dire exhaustion, threw themselves upon the ground, – "their tongues hanging out of their mouths,” says Colonel Stedman, “like those of dogs after a chase.” Many had thrown away their muskets, and Pitcairn had lost his horse, with the elegant pistols which fired the first shots of the War of Independence, and which may be seen to-day, along with other trophies, in the town library of Lexington.

PITCAIRN’S PISTOLS

Percy’s timely arrival checked the pursuit for an hour, and gave the starved and weary men a chance for food and rest. A few houses were pillaged and set on fire, but at three o’clock General Heath and Dr. Warren arrived on the scene and took command of the militia, and the irregular fight was renewed. When Percy reached Menotomy (now Arlington), seven miles from Boston, his passage was disputed by a fresh force of militia, while pursuers pressed hard on his rear, and it was only after an obstinate fight that he succeeded in forcing his way.

Retreat continued from Lexington to CharlestownThe roadside now fairly swarmed with marksmen, insomuch that, as one of the British officers observed, “they seemed to have dropped from the clouds.” It became impossible to keep order or to carry away the wounded; and when, at sunset, the troops entered Charlestown, under the welcome shelter of the fleet, it was upon the full run. They were not a moment too soon, for Colonel Timothy Pickering, with 700 Essex militia, on the way to intercept them, had already reached Winter Hill; and had their road been blocked by this fresh force they must in all probability have surrendered.

FANCIFUL PICTURE OF THE CONCORD-LEXINGTON FIGHT

(From a contemporary French print)

On this eventful day the British lost 273 of their number, while the Americans lost 93. The expedition had been a failure, the whole British force had barely escaped capture, and it had been shown that the people could not be frightened into submission. It had been shown, too, how efficient the town system of organized militia might prove on a sudden emergency.

Rising of the country; the British besieged in BostonThe most interesting feature of the day is the rapidity and skill with which the different bodies of minute-men, marching from long distances, were massed at those points on the road where they might most effectually harass or impede the British retreat. The Danvers company marched sixteen miles in four hours to strike Lord Percy at Menotomy. The list of killed and wounded shows that contingents from at least twenty-three towns had joined in the fight before sundown. But though the pursuit was then ended, these men did not return to their homes, but hour by hour their numbers increased. At noon of that day the alarm had reached Worcester. Early next morning, Israel Putnam was ploughing a field at Pomfret, in Connecticut, when the news arrived. Leaving orders for the militia companies to follow, he jumped on his horse, and riding a hundred miles in eighteen hours, arrived in Cambridge on the morning of the 21st, just in time to meet John Stark with the first company from New Hampshire. At midday of the 20th the college green at New Haven swarmed with eager students and citizens, and Captain Benedict Arnold, gathering sixty volunteers from among them, placed himself at their head and marched for Cambridge, picking up recruits and allies at all the villages on the way. And thus, from every hill and valley in New England, on they came, till, by Saturday night, Gage found himself besieged in Boston by a rustic army of 16,000 men.

ST. JOHN’S CHURCH, RICHMOND[4]

Effects of the news

When the news of this affair reached England, five weeks later, it was received at first with incredulity, then with astonishment and regret. Slight as the contest had been, it remained undeniable that British troops had been defeated by what in England was regarded as a crowd of “peasants;” and it was felt besides that the chances for conciliation had now been seriously diminished. Burke said that now that the Americans had once gone so far as this, they could hardly help going farther; and in spite of the condemnation that had been lavished upon Gage for his inactivity, many people were now inclined to find fault with him for having precipitated a conflict just at the time when it was hoped that, with the aid of the New York loyalists, some sort of accommodation might be effected. There is no doubt that the news from Lexington thoroughly disconcerted the loyalists of New York for the moment, and greatly strengthened the popular party there. In a manifesto addressed to the city of London, the New York committee of correspondence deplored the conduct of Gage as rash and violent, and declared that all the horrors of civil war would never bring the Americans to submit to the unjust acts of Parliament. When Hancock and Adams arrived, on their way to the Congress, they were escorted through the city with triumphal honours. In Pennsylvania steps were immediately taken for the enlistment and training of a colonial militia, and every colony to the south of it followed the example.

Mecklenburg County Resolves, May 31, 1775The Scotch-Irish patriots of Mecklenburg county, in North Carolina, ventured upon a measure more decided than any that had yet been taken in any part of the country. On May 31st, the county committee of Mecklenburg affirmed that the joint address of the two Houses of Parliament to the king, in February, had virtually “annulled and vacated all civil and military commissions granted by the Crown, and suspended the constitutions of the colonies;” and that consequently “the provincial congress of each province, under the direction of the great Continental Congress, is invested with all the legislative and executive powers within their respective provinces, and that no other legislative or executive power does or can exist at this time in any of these colonies.” In accordance with this state of things, rules were adopted “for the choice of county officers, to exercise authority by virtue of this choice and independently of the British Crown, until Parliament should resign its arbitrary pretensions.” These bold resolves were entrusted to the North Carolina delegates to the Continental Congress, but were not formally brought before that body, as the delegates thought it best to wait for a while longer the course of events.

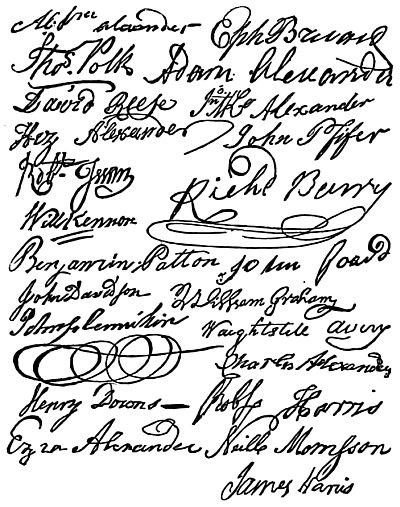

SIGNATURES OF MECKLENBURG COMMITTEE

Legend of the Mecklenburg “Declaration of Independence”

Some twenty years later they gave rise to the legend of the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence. The early writers of United States history passed over the proceedings of May 31st in silence, and presently the North Carolina patriots tried to supply an account of them from memory. Their traditional account was not published until 1819, when it was found to contain a spurious document, giving the substance of some of the foregoing resolves, decorated with phrases borrowed from the Declaration of Independence. This document purported to have been drawn up and signed at a county meeting on the 20th of May. A fierce controversy sprang up over the genuineness of the document, which was promptly called in question. For a long time many people believed in it, and were inclined to charge Jefferson with having plagiarized from it in writing the Declaration of Independence. But a minute investigation of all the newspapers of May, 1775, throughout the thirteen colonies, has revealed no trace of any such meeting on the 20th, and it is clear that no such document was made public. The story of the Mecklenburg Declaration is simply a legend based upon the distorted recollection of the real proceedings of May 31st.

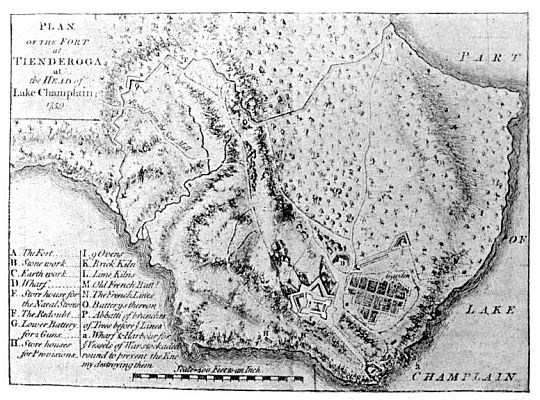

PLAN of the FORT at TICONDEROGA at the HEAD of Lake Champlain; 1759

Meanwhile, in New England, the warlike feeling had become too strong to be contented merely with defensive measures. No sooner had Benedict Arnold reached Cambridge than he suggested to Dr. Warren that an expedition ought to be sent without delay to capture Ticonderoga and Crown Point. These fortresses commanded the northern approaches to the Hudson river, the strategic centre of the whole country, and would be of supreme importance either in preparing an invasion of Canada or in warding off an invasion of New York.

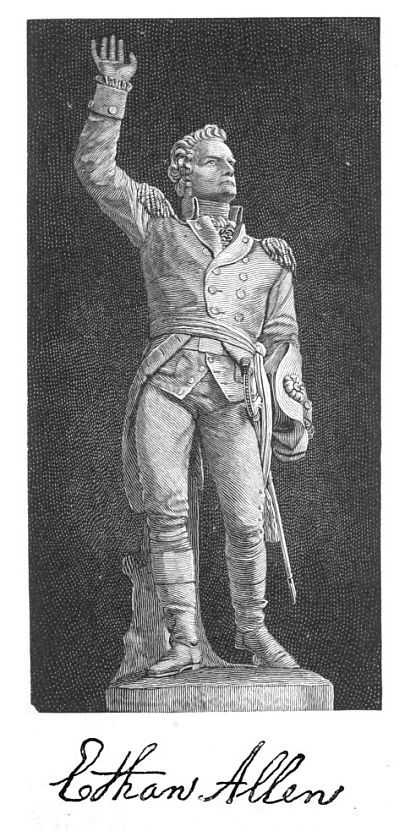

Benedict Arnold and Ethan AllenBesides this, they contained a vast quantity of military stores, of which the newly gathered army stood in sore need. The idea found favour at once. Arnold received a colonel’s commission from the Massachusetts Congress, and was instructed to raise 400 men among the Berkshire Hills, capture the fortresses, and superintend the transfer of part of their armament to Cambridge. When Arnold reached the wild hillsides of the Hoosac range, he found that he had a rival in the enterprise. The capture of Ticonderoga had also been secretly planned in Connecticut, and was entrusted to Ethan Allen, the eccentric but sagacious author of that now-forgotten deistical book, “The Oracles of Reason.” Allen was a leading spirit among the “Green Mountain Boys,” an association of Vermont settlers formed for the purpose of resisting the jurisdiction of New York, and his personal popularity was great. On the 9th of May Arnold overtook Allen and his men on their march toward Lake Champlain, and claimed the command of the expedition on the strength of his commission from Massachusetts; but the Green Mountain Boys were acting partly on their own account, partly under the direction of Connecticut. They cared nothing for the authority of Massachusetts, and knew nothing of Arnold; they had come out to fight under their own trusted leader. But few of Arnold’s own men had as yet assembled, and his commission could not give him command of Vermonters, so he joined the expedition as a volunteer. On reaching the lake that night, they found there were not nearly enough row-boats to convey the men across. But delay was not to be thought of. The garrison must not be put on its guard. Accordingly, with only eighty-three men, Allen and Arnold crossed the lake at daybreak of the 10th, and entered Ticonderoga side by side.

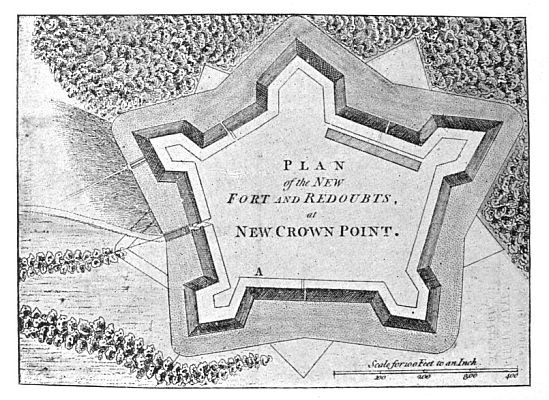

Capture of Ticonderoga and Crown Point, May 10, 1775The little garrison, less than half as many in number, as it turned out, was completely surprised, and the stronghold was taken without a blow. As the commandant jumped out of bed, half awake, he confusedly inquired of Allen by whose authority he was acting. “In the name of the Great Jehovah and the Continental Congress!” roared the bellicose philosopher, and the commandant, seeing the fort already taken, was fain to acquiesce. At the same time Crown Point surrendered to another famous Green Mountain Boy, Seth Warner, and thus more than two hundred cannon, with a large supply of powder and ball, were obtained for the New England army. A few days later, as some of Arnold’s own men arrived from Berkshire, he sailed down Lake Champlain, and captured St. John’s with its garrison; but the British recovered it in the course of the summer, and planted such a force there that in the next autumn we shall see it able to sustain a siege of fifty days.

PLAN of the New FORT AND REDOUBTS at NEW CROWNE POINT

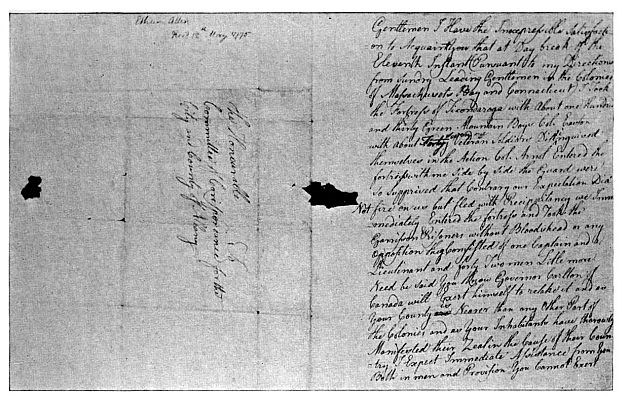

FACSIMILE OF ETHAN ALLEN’S LETTER ANNOUNCING THE CAPTURE OF TICONDEROGA

Neither Connecticut nor Massachusetts had any authority over these posts save through right of conquest. As it was Connecticut that had set Allen’s expedition on foot, Massachusetts yielded the point as to the disposal of the fortresses and their garrisons. Dr. Warren urged the Connecticut government to appoint Arnold to the command, so that his commission might be held of both colonies; but Connecticut preferred to retain Allen, and in July Arnold returned to Cambridge to mature his remarkable plan for invading Canada through the trackless wilderness of Maine. His slight disagreement with Allen bore evil fruit. As is often the case in such affairs, the men were more zealous than their commanders; there were those who denounced Arnold as an interloper, and he was destined to hear from them again and again.

WASHINGTON AT THE AGE OF FORTY

Second meeting of the Continental Congress, May 10, 1775

On the same day[5] on which Ticonderoga surrendered, the Continental Congress met at Philadelphia. The Adamses and the Livingstons, Jay, Henry, Washington, and Lee were there, as also Franklin, just back from his long service in England. Of all the number, John Adams and Franklin had now, probably, come to agree with Samuel Adams that a political separation from Great Britain was inevitable; but all were fully agreed that any consideration of such a question was at present premature and uncalled for. The Congress was a body which wielded no technical legal authority; it was but a group of committees, assembled for the purpose of advising with each other regarding the public weal. Yet something very like a state of war existed in a part of the country, under conditions which intimately concerned the whole, and in the absence of any formally constituted government something must be done to provide for such a crisis. The spirit of the assembly was well shown in its choice of a president. Peyton Randolph being called back to Virginia to preside over the colonial assembly, Thomas Jefferson was sent to the Congress in his stead; and it also became necessary for Congress to choose a president to succeed him. The proscribed John Hancock was at once chosen, and Benjamin Harrison, in conducting him to the chair, said, “We will show Great Britain how much we value her proscriptions.” To the garrisoning of Ticonderoga and Crown Point by Connecticut, the Congress consented only after much hesitation, since the capture of these posts had been an act of offensive warfare. But without any serious opposition, in the name of the “United Colonies,” the Congress adopted the army of New England men besieging Boston as the “Continental Army,” and proceeded to appoint a commander-in-chief to direct its operations. Practically, this was the most important step taken in the whole course of the War of Independence.

Appointment of Washington to command the Continental armyNothing less than the whole issue of the struggle, for ultimate defeat or for ultimate victory, turned upon the selection to be made at this crisis. For nothing can be clearer than that in any other hands than those of George Washington the military result of the war must have been speedily disastrous to the Americans. In appointing a Virginian to the command of a New England army, the Congress showed rare wisdom. It would well have accorded with local prejudices had a New England general been appointed. John Hancock greatly desired the appointment, and seems to have been chagrined at not receiving it. But it was wisely decided that the common interest of all Americans could in no way be more thoroughly engaged in the war than by putting the New England army in charge of a general who represented in his own person the greatest of the Southern colonies. Washington was now commander of the militia of Virginia, and sat in Congress in his colonel’s uniform. His services in saving the remnant of Braddock’s ill-fated army, and afterwards in the capture of Fort Duquesne, had won for him a military reputation greater than that of any other American. Besides this, there was that which, from his early youth, had made it seem right to entrust him with commissions of extraordinary importance. Nothing in Washington’s whole career is more remarkable than the fact that when a mere boy of twenty-one he should have been selected by the governor of Virginia to take charge of that most delicate and dangerous diplomatic mission to the Indian chiefs and the French commander at Venango. Consummate knowledge of human nature as well as of wood-craft, a courage that no threats could daunt and a clear intelligence that no treachery could hoodwink, were the qualities absolutely demanded by such an undertaking; yet the young man acquitted himself of his perilous task not merely with credit, but with splendour. As regards booklore, his education had been but meagre, yet he possessed in the very highest degree the rare faculty of always discerning the essential facts in every case, and interpreting them correctly. In the Continental Congress there sat many who were superior to him in learning and eloquence; but “if,” said Patrick Henry, “you speak of solid information and sound judgment, Colonel Washington is unquestionably the greatest man upon that floor.” Thus did that wonderful balance of mind – so great that in his whole career it would be hard to point out a single mistake – already impress his ablest contemporaries. Hand in hand with this rare soundness of judgment there went a completeness of moral self-control, which was all the more impressive inasmuch as Washington’s was by no means a tame or commonplace nature, such as ordinary power of will would suffice to guide. He was a man of intense and fiery passions. His anger, when once aroused, had in it something so terrible that strong men were cowed by it like frightened children. This prodigious animal nature was habitually curbed by a will of iron, and held in the service of a sweet and tender soul, into which no mean or unworthy thought had ever entered. Whole-souled devotion to public duty, an incorruptible integrity which no appeal to ambition or vanity could for a moment solicit, – these were attributes of Washington, as well marked as his clearness of mind and his strength of purpose. And it was in no unworthy temple that Nature had enshrined this great spirit. His lofty stature (exceeding six feet), his grave and handsome face, his noble bearing and courtly grace of manner, all proclaimed in Washington a king of men.

The choice of Washington for commander-in-chief was suggested and strongly urged by John Adams, and when, on the 15th of June, the nomination was formally made by Thomas Johnson of Maryland, it was unanimously confirmed. Then Washington, rising, said with great earnestness: “Since the Congress desire, I will enter upon the momentous duty, and exert every power I possess in their service and for the support of the glorious cause. But I beg it may be remembered by every gentleman in the room that I this day declare, with the utmost sincerity, I do not think myself equal to the command I am honoured with.” He refused to take any pay for his services, but said he would keep an accurate account of his personal expenses, which Congress might reimburse, should it see fit, after the close of the war.

While these things were going on at Philadelphia, the army of New England men about Boston was busily pressing, to the best of its limited ability, the siege of that town.

Siege of BostonThe army extended in a great semicircle of sixteen miles, – averaging about a thousand men to the mile, – all the way from Jamaica Plain to Charlestown Neck.

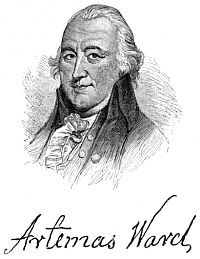

The headquarters were at Cambridge, where some of the university buildings were used for barracks, and the chief command had been entrusted to General Artemas Ward, under the direction of the committee of safety. Dr. Warren had succeeded Hancock as president of the provincial congress, which was in session at Watertown. The army was excellent in spirit, but poorly equipped and extremely deficient in discipline. Its military object was to compel the British troops to evacuate Boston and take to their ships, for as there was no American fleet, anything like the destruction or capture of the British force was manifestly impossible. The only way in which Boston could be made untenable for the British was by seizing and fortifying some of the neighbouring hills which commanded the town, of which the most important were those in Charlestown on the north and in Dorchester on the southeast. To secure these hills was indispensable to Gage, if he was to keep his foothold in Boston; and as soon as Howe, Clinton, and Burgoyne arrived, on the 25th of May, with reinforcements which raised the British force to 10,000 men, a plan was laid for extending the lines so as to cover both Charlestown and Dorchester.

Gage’s proclamationFeeling now confident of victory, Gage issued a proclamation on June 12th, offering free pardon to all rebels who should lay down their arms and return to their allegiance, saving only those ring leaders, John Hancock and Samuel Adams, whose crimes had been “too flagitious to be condoned.” At the same time, all who should be taken in arms were threatened with the gallows. In reply to this manifesto, the committee of safety, having received intelligence of Gage’s scheme, ordered out a force of 1,200 men, to forestall the governor, and take possession of Bunker Hill in Charlestown. At sunset of the 16th this brigade was paraded on Cambridge Common, and after prayer had been offered by Dr. Langdon, president of the university, they set out on their enterprise, under command of Colonel Prescott of Pepperell, a veteran of the French war, grandfather of one of the most eminent of American historians. On reaching the grounds, a consultation was held, and it was decided, in accordance with the general purpose, if not in strict conformity to the letter of the order, to push on farther and fortify the eminence known as Breed’s Hill, which was connected by a ridge with Bunker Hill, and might be regarded as part of the same locality.

The position of Breed’s Hill was admirably fitted for annoying the town and the ships in the harbour, and it was believed that, should the Americans succeed in planting batteries there, the British would be obliged to retire from Boston. There can be little doubt, however, that in thus departing from the strict letter of his orders Prescott made a mistake, which might have proved fatal, had not the enemy blundered still more seriously. The advanced position on Breed’s Hill was not only exposed to attacks in the rear from an enemy who commanded the water, but the line of retreat was ill secured, and, by seizing upon Charlestown Neck, it would have been easy for the British, with little or no loss, to have compelled Prescott to surrender. From such a disaster the Americans were saved by the stupid contempt which the enemy felt for them.