полная версия

полная версияThe American Revolution

Lafayette’s suspicions were now aroused, and he sent a dispatch in all haste to Washington, saying that his presence in the field was sorely needed. The army was bewildered. Fighting had hardly begun, but their position was obviously so good that the failure to make prompt use of it suggested some unknown danger. One of the divisions on the left was now ordered back by Lee, and the others, seeing this retrograde movement, and understanding it as the prelude to a general retreat, began likewise to fall back. All thus retreated, though without flurry or disorder, to the high ground just east of the second ravine which they had crossed in their advance. All the advantage of their offensive movement was thus thrown away without a struggle, but the position they had now reached was excellent for a defensive fight. To the amazement of everybody, Lee ordered the retreat to be continued across the marshy ravine. As they crowded upon the causeway the ranks began to fall into some disorder. Many sank exhausted from the heat. No one could tell from what they were fleeing, and the exultant ardour with which they had begun to enfold the British line gave place to bitter disappointment, which vented itself in passionate curses. So they hurried on, with increasing disorder, till they approached the brink of the westerly ravine, where their craven commander met Washington riding up.

Washington retrieves the situationThe men who then beheld Washington’s face and listened to his outburst of wrath could never forget it for the rest of their lives. It was one of those moments that live in tradition. People of to-day, who know nothing else about Charles Lee, think of him vaguely as the man whom Washington upbraided at Monmouth. People who know nothing else about the battle of Monmouth still dimly associate the name with the disgrace of a General Lee. Not many words were wasted.[17] Leaving the traitor cowering and trembling in his stirrups, Washington hurried on to rally the troops and form a new front. There was not a moment to lose, for the British were within a mile of them, and their fire began before the line of battle could be formed. To throw a mass of disorderly fugitives in the face of advancing reinforcements, as Lee had been on the point of doing, was to endanger the organization of the whole force. It was now that the admirable results of Steuben’s teaching were to be seen. The retreating soldiers immediately wheeled and formed under fire with as much coolness and precision as they could have shown on parade, and while they stopped the enemy’s progress, Washington rode back and brought up the main body of his army. On some heights to the left of the enemy Greene placed a battery which enfiladed their lines with deadly effect, while Wayne attacked them vigorously in front. After a brave resistance, the British were driven back upon the second ravine which Lee had crossed in the morning’s advance. Washington now sent word to Steuben, who was a couple of miles in the rear, telling him to bring up three brigades and press the retreating enemy. Some time before this he had again met Lee and ordered him to the rear, for his suspicion was now thoroughly aroused. As the traitor rode away from the field, baffled and full of spite, he met Steuben advancing, and tried to work one final piece of mischief. He tried to persuade Steuben to halt, alleging that he must have misunderstood Washington’s orders; but the worthy baron was not to be trifled with, and doggedly kept on his way.[18] The British were driven in some confusion across the ravine, and were just making a fresh stand on the high ground east of it when night put an end to the strife. Washington sent out parties to attack them on both flanks as soon as day should dawn; but Clinton withdrew in the night, taking with him many of his wounded men, and by daybreak had joined Knyphausen on the heights of Middletown, whither it was useless to follow him.

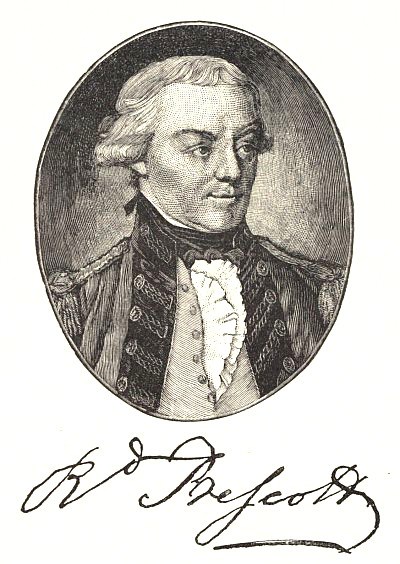

CHARLES LEE

It was a drawn battle

The total American loss in the battle of Monmouth was 362. The British loss is commonly given as 416, but must have been much greater. According to Washington’s own account, the Americans buried on the battlefield 245 British dead, but could not count the wounded, as so many had been carried away; from the ordinary proportion of four or five wounded to one man killed, he estimates the number at from 1,000 to 1,200.[19] More than 100 of the British were taken prisoners. On both sides there were many deaths from sunstroke. The battle has usually been claimed as a victory for the Americans; and so it was in a certain sense, as they drove the enemy from the field. Strategically considered, however, Lord Stanhope is quite right in calling it a drawn battle. The purpose for which Washington undertook it was foiled by the treachery of Lee. Nevertheless, in view of the promptness with which Washington turned defeat into victory, and of the greatly increased efficiency which it showed in the soldiers, the moral advantage was doubtless with the Americans. It deepened the impression produced by the recovery of Philadelphia, it silenced the cavillers against Washington,[20] and its effect upon Clinton’s army was disheartening. More than 2,000 of his men, chiefly Hessians, deserted in the course of the following week.

During the night after the battle, the behaviour of Lee was the theme of excited discussion among the American officers. By the next day, having recovered his self-possession, he wrote a petulant letter to Washington, demanding an apology for his language on the battlefield. Washington’s reply was as follows: —

Washington’s letter to Lee“Sir, – I received your letter, expressed, as I conceive, in terms highly improper. I am not conscious of making use of any very singular expressions at the time of meeting you, as you intimate. What I recollect to have said was dictated by duty and warranted by the occasion. As soon as circumstances will permit, you shall have an opportunity of justifying yourself to the army, to Congress, to America, and to the world in general; or of convincing them that you were guilty of a breach of orders, and of misbehaviour before the enemy on the 28th instant, in not attacking them as you had been directed, and in making an unnecessary, disorderly, and shameful retreat.”

Trial and sentence of LeeTo this terrible letter Lee sent the following impudent answer: “You cannot afford me greater pleasure than in giving me the opportunity of showing to America the sufficiency of her respective servants. I trust that temporary power of office and the tinsel dignity attending it will not be able, by all the mists they can raise, to obfuscate the bright rays of truth.” Washington replied by putting Lee under arrest. A court-martial was at once convened, before which he was charged with disobedience of orders in not attacking the enemy, with misbehaviour on the field in making an unnecessary and shameful retreat, and, lastly, with gross disrespect to the commander-in-chief. After a painstaking trial, which lasted more than a month, he was found guilty on all three charges, and suspended from command in the army for the term of one year.

This absurdly inadequate sentence is an example of the extreme and sometimes ill-judged humanity which has been wont to characterize judicial proceedings in America. Many a European soldier has been ruthlessly shot for less serious misconduct. A commander can be guilty of no blacker crime than knowingly to betray his trust on the field of battle. But in Lee’s case, the very enormity of his crime went far to screen him from the punishment which it deserved. People are usually slow to believe in criminality that goes far beyond the ordinary wickedness of the society in which they live. If a candidate for Congress is accused of bribery or embezzlement, we unfortunately find it easy to believe the charge; but if he were to be accused of attempting to poison his rival, we should find it very hard indeed to believe it. In the France of Catherine de’ Medici or the Italy of Cæsar Borgia, the one accusation would have been as credible as the other, but we have gone far toward outgrowing some of the grosser forms of crime. In American history, as in modern English history, instances of downright treason have been very rare; and in proportion as we are impressed with their ineffable wickedness are we slow to admit the possibility of their occurrence. In ancient Greece and in mediæval Italy there were many Benedict Arnolds; in the United States a single plot for surrendering a stronghold to the enemy has consigned its author to a solitary immortality of infamy. But unless the proof of Arnold’s treason had been absolutely irrefragable, many persons would have refused to believe it. In like manner, people were slow to believe that Lee could have been so deliberately wicked as to plan the defeat of the army in which he held so high a command, and some historians have preferred to regard his conduct as wholly unintelligible, rather than adopt the only clue by which it can be explained. He might have been bewildered, he might have been afraid, he might have been crazy, it was suggested; and to the latter hypothesis his well-known eccentricity gave some countenance. It was perhaps well for the court-martial to give him the benefit of the doubt, but in any case it should have been obvious that he had proved himself permanently unfit for a command.

CARICATURE OF CHARLES LEE

Lee’s character and schemes

Historians for a long time imitated the clemency of the court-martial by speaking of the “waywardness” of General Lee. Nearly eighty years elapsed before the discovery of that document which justifies us in putting the worst interpretation upon his acts, while it enables us clearly to understand the motives which prompted them. Lee was nothing but a selfish adventurer. He had no faith in the principles for which the Americans were fighting, or indeed in any principles. He came here to advance his own fortunes, and hoped to be made commander-in-chief. Disappointed in this, he began at once to look with hatred and envy upon Washington, and sought to thwart his purposes, while at the same time he intrigued with the enemy. He became infatuated with the idea of playing some such part in the American Revolution as Monk had played in the Restoration of Charles II. This explains his conduct in the autumn of 1776, when he refused to march to the support of Washington. Should Washington be defeated and captured, then Lee, as next in command and at the head of a separate army, might negotiate for peace. His conduct as prisoner in New York, first in soliciting an interview with Congress, then in giving aid and counsel to the enemy, is all to be explained in the same way. And his behaviour in the Monmouth campaign was part and parcel of the same crooked policy. Lord North’s commissioners had just arrived from England to offer terms to the Americans, but in the exultation over Saratoga and the French alliance, now increased by the recovery of Philadelphia, there was little hope of their effecting anything. The spirits of these Yankees, thought Lee, must not be suffered to rise too high, else they will never listen to reason. So he wished to build a bridge of gold for Clinton to retreat by; and when he found it impossible to prevent an attack, his second thoughts led him to take command, in order to keep the game in his own hands. Should Washington now incur defeat by adopting a course which Lee had emphatically condemned as impracticable, the impatient prejudices upon which the cabal had played might be revived. The downfall of Washington would perhaps be easy to compass; and the schemer would thus not only enjoy the humiliation of the man whom he so bitterly hated, but he might fairly hope to succeed him in the chief command, and thus have an opportunity of bringing the war to a “glorious” end through a negotiation with Lord North’s commissioners. Such thoughts as these were, in all probability, at the bottom of Lee’s extraordinary behaviour at Monmouth. They were the impracticable schemes of a vain, egotistical dreamer. That Washington and Chatham, had that great statesman been still alive, might have brought the war to an honourable close through open and frank negotiation was perhaps not impossible. That such a man as Lee, by paltering with agents of Lord North, should effect anything but mischief and confusion was inconceivable. But selfishness is always incompatible with sound judgment, and Lee’s wild schemes were quite in keeping with his character. The method he adopted for carrying them out was equally so. It would have been impossible for a man of strong military instincts to have relaxed his clutch upon an enemy in the field, as Lee did at the battle of Monmouth. If Arnold had been there that day, with his head never so full of treason, an irresistible impulse would doubtless have led him to attack the enemy tooth and nail, and the treason would have waited till the morrow.

As usually happens in such cases, the selfish schemer overreached himself. Washington won a victory, after all; the treachery was detected, and the traitor disgraced. Maddened by the destruction of his air-castles, Lee now began writing scurrilous articles in the newspapers. He could not hear Washington’s name mentioned without losing his temper, and his venomous tongue at length got him into a duel with Colonel Laurens, one of Washington’s aids and son of the president of Congress. He came out of the affair with nothing worse than a wound in the side; but when, a little later, he wrote an angry letter to Congress, he was summarily expelled from the army. “Ah, I see,” he said, aiming a Parthian shot at Washington, “if you wish to become a great general in America, you must learn to grow tobacco;” and so he retired to a plantation which he had in the Shenandoah valley.

His deathHe lived to behold the triumph of the cause which he had done so much to injure, and in October, 1782, he died in a mean public-house in Philadelphia, friendless and alone. His last wish was that he might not be buried in consecrated ground, or within a mile of any church or meeting-house, because he had kept so much bad company in this world that he did not choose to continue it in the next. But in this he was not allowed to have his way. He was buried in the cemetery of Christ Church in Philadelphia, and many worthy citizens came to the funeral.

CHRIST CHURCH, PHILADELPHIA

The situation at New York

When Washington, after the battle of Monmouth, saw that it was useless further to molest Clinton’s retreat, he marched straight for the Hudson river, and on the 20th of July he encamped at White Plains, while his adversary took refuge in New York. The opposing armies occupied the same ground as in the autumn of 1776; but the Americans were now the aggressive party. Howe’s object in 1776 was the capture of Washington’s army; Clinton’s object in 1778 was limited to keeping possession of New York. There was now a chance for testing the worth of the French alliance. With the aid of a powerful French fleet, it might be possible to capture Clinton’s army, and thus end the war at a blow. But this was not to be. The French fleet of twelve ships-of-the-line and six frigates, commanded by the Count d’Estaing, sailed from Toulon on the 13th of April, and after a tedious struggle with head-winds arrived at the mouth of the Delaware on the 8th of July, just too late to intercept Lord Howe’s squadron. The fleet contained a land force of 4,000 men, and brought over M. Gérard, the first minister from France to the United States. Finding nothing to do on the Delaware, the count proceeded to Sandy Hook, where he was boarded by Washington’s aids, Laurens and Hamilton, and a council of war was held. As the British fleet in the harbour consisted of only six ships-of-the-line, with several frigates and gunboats, it seemed obvious that it might be destroyed or captured by Estaing’s superior force, and then Clinton would be entrapped in the island city. But this plan was defeated by a strange obstacle.

The French fleet unable to enter the harbourThough the harbour of New York is one of the finest in the world, it has, like most harbours situated at the mouths of great rivers, a bar at the entrance, which in 1778 was far more troublesome than it is to-day. Since that time the bar has shifted its position and been partially worn away, so that the largest ships can now freely enter, except at low tide. But when the American pilots examined Estaing’s two largest ships, which carried eighty and ninety guns respectively, they declared it unsafe, even at high tide, for them to venture upon the bar. The enterprise was accordingly abandoned, but in its stead another one was undertaken, which, if successful, might prove hardly less decisive than the capture of New York.

After their expulsion from Boston in the first year of the war, the British never regained their foothold upon the mainland of New England. But in December, 1776, the island which gives its name to the state of Rhode Island had been seized by Lord Percy, and the enemy had occupied it ever since. From its commanding position at the entrance to the Sound, it assisted them in threatening the Connecticut coast; and, on the other hand, should occasion require, it might even enable them to threaten Boston with an overland attack. After Lord Percy’s departure for England in the spring of 1777, the command devolved upon Major-general Richard Prescott, an unmitigated brute. Under his rule no citizen of Newport was safe in his own house. He not only arrested people and threw them into jail without assigning any reason, but he encouraged his soldiers in plundering houses and offering gross insults to ladies, as well as in cutting down shade-trees and wantonly defacing the beautiful lawns. A great loud-voiced, irascible fellow, swelling with the sense of his own importance, if he chanced to meet with a Quaker who failed to take off his hat, he would seize him by the collar and knock his head against the wall, or strike him over the shoulders with the big gnarled stick which he usually carried. One night in July, as this petty tyrant was sleeping at a country house about five miles from Newport, a party of soldiers rowed over from the mainland in boats, under the guns of three British frigates, and, taking the general out of bed, carried him off in his night-gown. He was sent to Washington’s headquarters on the Hudson. As he passed through the village of Lebanon, in Connecticut, he stopped to dine at an old inn kept by one Captain Alden. He was politely received, and in the course of the meal Mrs. Alden set upon the table a dish of succotash, whereupon Prescott, not knowing the delicious dish, roared, “What do you mean by offering me this hog’s food?” and threw it all upon the floor.

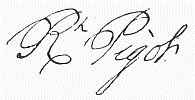

The good woman retreated in tears to the kitchen, and presently her husband, coming in with a stout horsewhip, dealt with the boor as he deserved. When Prescott was exchanged for General Lee, in April, 1778, he resumed the command at Newport, but was soon superseded by the amiable and accomplished Sir Robert Pigot, under whom the garrison was increased to 6,000 men.

Attempt to capture the British garrison at NewportNew York and Newport were now the only places held by the enemy in the United States, and the capture of either, with its army of occupation, would be an event of prime importance. As soon as the enterprise was suggested, the New England militia began to muster in force, Massachusetts sending a strong contingent under John Hancock. General Sullivan had been in command at Providence since April. Washington now sent him 1,500 picked men of his Continental troops, with Greene, who was born hard by and knew every inch of the island; with Glover, of amphibious renown; and Lafayette, who was a kinsman of the Count d’Estaing. The New England yeomanry soon swelled this force to about 9,000, and with the 4,000 French regulars and the fleet, it might well be hoped that General Pigot would quickly be brought to surrender.

The expedition failed through the inefficient coöperation of the French and the insubordination of the yeomanry. Estaing arrived off the harbour of Newport on the 29th of July, and had a conference with Sullivan. It was agreed that the Americans should land upon the east side of the island while the French were landing upon the west side, thus intervening between the main garrison at Newport and a strong detachment which was stationed on Butts Hill, at the northern end of the island. By such a movement this detachment might be isolated and captured, to begin with. But General Pigot, divining the purpose of the allies, withdrew the detachment, and concentrated all his forces in and around the city. At this moment the French troops were landing upon Conanicut island, intending to cross to the north of Newport on the morrow, according to the agreement.

Sullivan seizes Butts HillSullivan did not wait for them, but seeing the commanding position on Butts Hill evacuated, he rightly pushed across the channel and seized it, while at the same time he informed Estaing of his reasons for doing so. The count, not understanding the situation, was somewhat offended at what he deemed undue haste on the part of Sullivan, but thus far nothing had happened to disturb the execution of their scheme. He had only to continue landing his troops and blockade the southern end of the island with his fleet, and Sir Robert Pigot was doomed. But the next day Lord Howe appeared off Point Judith, with thirteen ships-of-the line, seven frigates, and several small vessels, and Estaing, reëmbarking the troops he had landed on Conanicut, straightway put out to sea to engage him. For two days the hostile fleets manœuvred for the weather-gage, and just as they were getting ready for action there came up a terrific storm, which scattered them far and wide. Instead of trying to destroy one another, each had to bend all his energies to saving himself.

Naval battle prevented by stormSo fierce was the storm that it was remembered in local tradition as lately as 1850 as “the Great Storm.” Windows in the town were incrusted with salt blown up in the ocean spray. Great trees were torn up by the roots, and much shipping was destroyed along the coast.

It was not until the 20th of August that Estaing brought in his squadron, somewhat damaged from the storm. He now insisted upon going to Boston to refit, in accordance with general instructions received from the ministry before leaving home. It was urged in vain by Greene and Lafayette that the vessels could be repaired as easily in Narragansett Bay as in Boston harbour; that by the voyage around Cape Cod, in his crippled condition, he would only incur additional risk; that by staying he would strictly fulfil the spirit of his instructions; that an army had been brought here, and stores collected, in reliance upon his aid; that if the expedition were to be ruined through his failure to coöperate, it would sully the honour of France and give rise to hard feelings in America; and finally, that even if he felt constrained, in spite of sound arguments, to go and refit at Boston, there was no earthly reason for his taking the 4,000 French soldiers with him. The count was quite disposed to yield to these sensible remonstrances, but on calling a council of war he found himself overruled by his officers. Estaing was not himself a naval officer, but a lieutenant-general in the army, and it has been said that the officers of his fleet, vexed at having a land-lubber put over them, were glad of a chance to thwart him in his plans. However this may have been, it was voted that the letter of the royal instructions must be blindly adhered to, and so on the 23d Estaing weighed anchor for Boston, taking the land forces with him, and leaving General Sullivan in the lurch.