полная версия

полная версияThe American Revolution

But the most dangerous ground upon which Congress ventured during the whole course of the war was connected with the dark intrigues of those officers who wished to have Washington removed from the chief command that Gates might be put in his place. We have seen how successful Gates had been in supplanting Schuyler on the eve of victory.

Gates is puffed up with successWithout having been under fire or directing any important operation, Gates had carried off the laurels of the northern campaign. From many persons, no doubt, he got credit even for what had happened before he joined the army, on the 19th of August. His appointment dated from the 2d, before either the victory of Stark or the discomfiture of St. Leger; and it was easy for people to put dates together uncritically, and say that before the 2d of August Burgoyne had continued to advance into the country, and nothing could check him until after Gates had been appointed to command. The very air rang with the praises of Gates, and his weak head was not unnaturally turned with so much applause. In his dispatches announcing the surrender of Burgoyne, he not only forgot to mention the names of Arnold and Morgan, who had won for him the decisive victory, but he even seemed to forget that he was serving under a commander-in-chief, for he sent his dispatches directly to Congress, leaving Washington to learn of the event through hearsay. Thirteen days after the surrender, Washington wrote to Gates, congratulating him upon his success. “At the same time,” said the letter, “I cannot but regret that a matter of such magnitude, and so interesting to our general operations, should have reached me by report only, or through the channels of letters not bearing that authenticity which the importance of it required, and which it would have received by a line over your signature stating the simple fact.”

But, worse than this, Gates kept his victorious army idle at Saratoga after the whole line of the Hudson was cleared of the enemy, and would not send reinforcements to Washington.

and shows symptoms of insubordinationCongress so far upheld him in this as to order that Washington should not detach more than 2,500 men from the northern army without consulting Gates and Governor Clinton. It was only with difficulty that Washington, by sending Colonel Hamilton with a special message, succeeded in getting back Morgan with his riflemen. When reinforcements finally did arrive, it was too late. Had they come more promptly, Howe would probably have been unable to take the forts on the Delaware, without control of which he could not have stayed in Philadelphia. But the blame for the loss of the forts was by many people thrown upon Washington, whose recent defeats at Brandywine and Germantown were now commonly contrasted with the victories at the North.

The moment seemed propitious for Gates to try his peculiar strategy once more, and displace Washington as he had already displaced Schuyler. Assistants were not wanting for this dirty work. Among the foreign adventurers then with the army was one Thomas Conway, an Irishman, who had been for a long time in the French service, and, coming over to America, had taken part in the Pennsylvania campaign. Washington had opposed Conway’s claims for undue promotion, and the latter at once threw himself with such energy into the faction then forming against the commander-in-chief that it soon came to be known as the “Conway Cabal.” The other principal members of the cabal were Thomas Mifflin, the quartermaster-general, and James Lovell, a delegate from Massachusetts, who had been Schuyler’s bitterest enemy in Congress.

It was at one time reported that Samuel Adams was in sympathy with the cabal, and the charge has been repeated by many historians, but it seems to have originated in a malicious story set on foot by some of the friends of John Hancock. At the beginning of the war, Hancock, whose overweening vanity often marred his usefulness, had hoped to be made commander-in-chief, and he never forgave Samuel Adams for preferring Washington for that position. In the autumn of 1777, Hancock resigned his position as president of Congress, and was succeeded by Henry Laurens, of South Carolina. On the day when Hancock took leave of Congress, a motion was made to present him with the thanks of that body in acknowledgment of his admirable discharge of his duty; but the New England delegates, who had not been altogether satisfied with him, defeated the motion on general grounds, and established the principle that it was injudicious to pass such complimentary votes in the case of any president. This action threw Hancock into a rage, which was chiefly directed against Samuel Adams as the most prominent member of the delegation; and after his return to Boston it soon became evident that he had resolved to break with his old friend and patron. Artful stories, designed to injure Adams, were in many instances traced to persons who were in close relation with Hancock. After the fall of the cabal, no more deadly stab could be dealt to the reputation of any man than to insinuate that he had given it aid or sympathy; and there is good ground for believing that such reports concerning Adams were industriously circulated by unscrupulous partisans of the angry Hancock. The story was revived at a later date by the friends of Hamilton, on the occasion of the schism between Hamilton and John Adams, but it has not been well sustained. The most plausible falsehoods, however, are those which are based upon misconstrued facts; and it is certain that Samuel Adams had not only favoured the appointment of Gates in the North, but he had sometimes spoken with impatience of the so-called Fabian policy of Washington. In this he was like many other ardent patriots whose military knowledge was far from commensurate with their zeal. His cousin, John Adams, was even more outspoken. He declared himself “sick of Fabian systems.” “My toast,” he said, “is a short and violent war;” and he complained of the reverent affection which the people felt for Washington as an “idolatry” dangerous to American liberty. It was by working upon such impatient moods as these, in which high-minded men like the Adamses sometimes indulged, that unscrupulous men like Gates hoped to attain their ends.

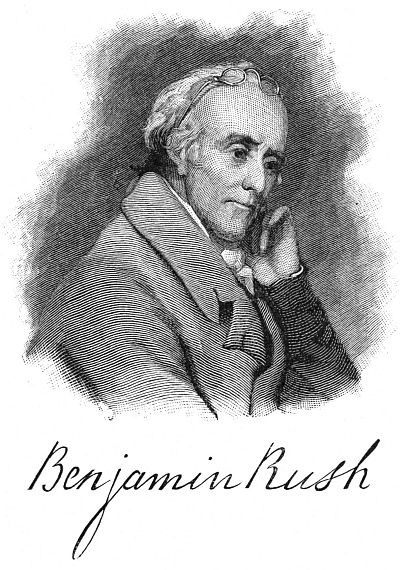

The first fruits of the cabal in Congress were seen in the reorganization of the Board of War in November, 1777. Mifflin was chosen a member of the board, and Gates was made its president, with permission to serve in the field should occasion require it. Gates was thus, in a certain sense, placed over Washington’s head; and soon afterward Conway was made inspector-general of the army, with the rank of major-general. In view of Washington’s well-known opinions, the appointments of Mifflin and Conway might be regarded as an open declaration of hostility on the part of Congress. Some weeks before, in regard to the rumour that Conway was to be promoted, Washington had written, “It will be impossible for me to be of any further service, if such insuperable difficulties are thrown in my way.” Such language might easily be understood as a conditional threat of resignation, and Conway’s appointment was probably urged by the conspirators with the express intention of forcing Washington to resign. Should this affront prove ineffectual, they hoped, by dint of anonymous letters and base innuendoes, to make the commander’s place too hot for him. It was asserted that Washington’s army had all through the year outnumbered Howe’s more than three to one. The distress of the soldiers was laid at his door; the sole result, if not the sole object, of his many marches, according to James Lovell, was to wear out their shoes and stockings. An anonymous letter to Patrick Henry, then governor of Virginia, dated from York, where Congress was sitting, observed: “We have wisdom, virtue, and strength enough to save us, if they could be called into action. The northern army has shown us what Americans are capable of doing with a general at their head. The spirit of the southern army is no way inferior to the spirit of the northern. A Gates, a Lee, or a Conway would in a few weeks render them an irresistible body of men. Some of the contents of this letter ought to be made public, in order to awaken, enlighten, and alarm our country.” Henry sent this letter to Washington, who instantly recognized the well-known handwriting of Dr. Benjamin Rush. Another anonymous letter, sent to President Laurens, was still more emphatic: “It is a very great reproach to America to say there is only one general in it. The great success to the northward was owing to a change of commanders; and the southern army would have been alike successful if a similar change had taken place. The people of America have been guilty of idolatry by making a man their God, and the God of heaven and earth will convince them by woful experience that he is only a man; for no good can be expected from our army until Baal and his worshippers are banished from camp.” This mischievous letter was addressed to Congress, but, instead of laying it before that body, the high-minded Laurens sent it directly to Washington. But the commander-in-chief was forewarned, and neither treacherous missives like these, nor the direct affronts of Congress, were allowed to disturb his equanimity.

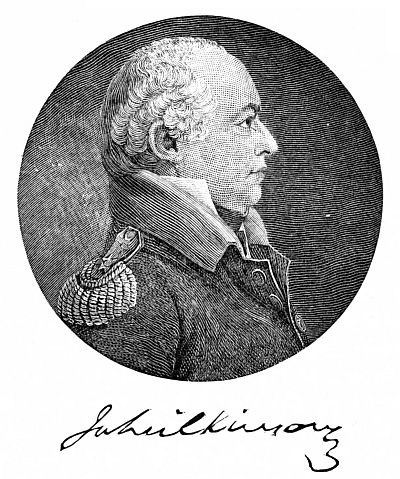

Conway’s letter to GatesJust before leaving Saratoga, Gates received from Conway a letter containing an allusion to Washington so terse and pointed as to be easily remembered and quoted, and Gates showed this letter to his young confidant and aid-de-camp, Wilkinson. A few days afterward, when Wilkinson had reached York with the dispatches relating to Burgoyne’s surrender, he fell in with a member of Lord Stirling’s staff, and under the genial stimulus of Monongahela whiskey repeated the malicious sentence. Thus it came to Stirling’s ears, and he straightway communicated it to Washington by letter, saying that he should always deem it his duty to expose such wicked duplicity. Thus armed, Washington simply sent to Conway the following brief note: —

“Sir, – A letter which I received last night contained the following paragraph: ‘In a letter from General Conway to General Gates, he says, Heaven has determined to save your country, or a weak General and bad counsellors would have ruined it.’ I am, sir, your humble servant.

George Washington.”

Conway knew not what sort of answer to make to this startling note. When Mifflin heard of it, he wrote at once to Gates, telling him that an extract from one of Conway’s letters had fallen into Washington’s hands, and advising him to take better care of his papers in future. All the plotters were seriously alarmed; for their scheme was one which would not bear the light for a moment, and Washington’s curt letter left them quite in the dark as to the extent of his knowledge. “There is scarcely a man living,” protested Gates, “who takes greater care of his papers than I do. I never fail to lock them up, and keep the key in my pocket.” One thing was clear: there must be no delay in ascertaining how much Washington knew and where he got his knowledge. After four anxious days it occurred to Gates that it must have been Washington’s aid-de-camp, Hamilton, who had stealthily gained access to his papers during his short visit to the northern camp. Filled with this idea, Gates chuckled as he thought he saw a way of diverting attention from the subject matter of the letters to the mode in which Washington had got possession of their contents. He sat down and wrote to the commander-in-chief, saying he had learned that some of Conway’s confidential letters to himself had come into his excellency’s hands: such letters must have been copied by stealth, and he hoped his excellency would assist him in unearthing the wretch who prowled about and did such wicked things, for obviously it was unsafe to have such creatures in the camp; they might disclose precious secrets to the enemy. And so important did the matter seem that he sent a duplicate of the present letter to Congress, in order that every imaginable means might be adopted for detecting the culprit without a moment’s delay. The purpose of this elaborate artifice was to create in Congress, which as yet knew nothing of the matter, an impression unfavourable to Washington, by making it appear that he encouraged his aids-de-camp in prying into the portfolios of other generals. For, thought Gates, it is as clear as day that Hamilton was the man; nobody else could have done it.

But Gates’s silly glee was short-lived. Washington discerned at a glance the treacherous purpose of the letter, and foiled it by the simple expedient of telling the plain truth. “Your letter,” he replied, “came to my hand a few days ago, and, to my great surprise, informed me that a copy of it had been sent to Congress, for what reason I find myself unable to account; but as some end was doubtless intended to be answered by it, I am laid under the disagreeable necessity of returning my answer through the same channel, lest any member of that honourable body should harbour an unfavourable suspicion of my having practised some indirect means to come at the contents of the confidential letters between you and General Conway.” After this ominous prelude, Washington went on to relate how Wilkinson had babbled over his cups, and a certain sentence from one of Conway’s letters had thereupon been transmitted to him by Lord Stirling. He had communicated this discovery to Conway, to let that officer know that his intriguing disposition was observed and watched. He had mentioned this to no one else but Lafayette, for he thought it indiscreet to let scandals arise in the army, and thereby “afford a gleam of hope to the enemy.” He had not known that Conway was in correspondence with Gates, and had even supposed that Wilkinson’s information was given with Gates’s sanction, and with friendly intent to forearm him against a secret enemy. “But in this,” he disdainfully adds, “as in other matters of late, I have found myself mistaken.”

HORATIO GATES

Gates tries, unsuccessfully, to save himself by lying

So the schemer had overreached himself. It was not Washington’s aid-de-camp who had pried, but it was Gates’s own aid who had blabbed. But for Gates’s treacherous letter, Washington would not even have suspected him; and, to crown all, he had only himself to thank for rashly blazoning before Congress a matter so little to his credit, and which Washington, in his generous discretion, would forever have kept secret. Amid this discomfiture, however, a single ray of hope could be discerned. It appeared that Washington had known nothing beyond the one sentence which had come to him as quoted in conversation by Wilkinson. A downright falsehood might now clear up the whole affair, and make Wilkinson the scapegoat for all the others. Gates accordingly wrote again to Washington, denying his intimacy with Conway, declaring that he had never received but a single letter from him, and solemnly protesting that this letter contained no such paragraph as that of which Washington had been informed. The information received through Wilkinson he denounced as a villainous slander. But these lies were too transparent to deceive any one, for in his first letter Gates had implicitly admitted the existence of several letters between himself and Conway, and his manifest perturbation of spirit had shown that these letters contained remarks that he would not for the world have had Washington see. A cold and contemptuous reply from Washington made all this clear, and put Gates in a very uncomfortable position, from which there was no retreat.

but is successful, as usual, in keeping from under fireWhen the matter came to the ears of Wilkinson, who had just been appointed secretary of the Board of War, and was on his way to Congress, his youthful blood boiled at once. He wrote bombastic letters to everybody, and challenged Gates to deadly combat. A meeting was arranged for sunrise, behind the Episcopal church at York, with pistols. At the appointed hour, when all had arrived on the ground, the old general requested, through his second, an interview with his young antagonist, walked up a back street with him, burst into tears, called him his dear boy, and denied that he had ever made any injurious remarks about him. Wilkinson’s wrath was thus assuaged for a moment, only to blaze forth presently with fresh violence, when he made inquiries of Washington, and was allowed to read the very letter in which his general had slandered him. He instantly wrote a letter to Congress, accusing Gates of treachery and falsehood, and resigned his position on the Board of War.

The forged lettersThese revelations strengthened Washington in proportion as they showed the malice and duplicity of his enemies. About this time a pamphlet was published in London, and republished in New York, containing letters which purported to have been written by Washington to members of his family, and to have been found in the possession of a mulatto servant taken prisoner at Fort Lee. The letters, if genuine, would have proved their author to be a traitor to the American cause; but they were so bunglingly concocted that every one knew them to be a forgery, and their only effect was to strengthen Washington still more, while throwing further discredit upon the cabal, with which many persons were inclined to connect them.

PISTOL GIVEN TO WASHINGTON BY LAFAYETTE

Scheme for invading Canada

The army and the people were now becoming incensed at the plotters, and the press began to ridicule them, while the reputation of Gates suffered greatly in Congress as the indications of his real character were brought to light. All that was needed to complete the discomfiture of the cabal was a military fiasco, and this was soon forthcoming. In order to detach Lafayette from Washington, a winter expedition against Canada was devised by the Board of War. Lafayette, a mere boy, scarcely twenty years old, was invited to take the command, with Conway for his chief lieutenant. It was said that the French population of Canada would be sure to welcome the high-born Frenchman as their deliverer from the British yoke; and it was further thought that the veteran Irish schemer might persuade his young commander to join the cabal, and bring to it such support as might be gained from the French alliance, then about to be completed. Congress was persuaded to authorize the expedition, and Washington was not consulted in the matter.

The dinner at YorkBut Lafayette knew his own mind better than was supposed. He would not accept the command until he had obtained Washington’s consent, and then he made it an indispensable condition that Baron de Kalb, who outranked Conway, should accompany the expedition. These preliminaries having been arranged, the young general went to York for his instructions.

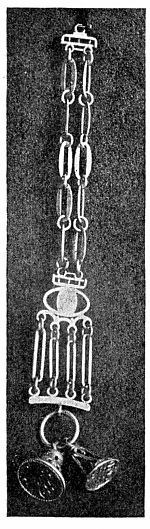

SEALS GIVEN TO WASHINGTONBY LAFAYETTE

There he found Gates, surrounded by schemers and sycophants, seated at a very different kind of dinner from that to which Lafayette had lately been used at Valley Forge. Hilarious with wine, the company welcomed the new guest with acclamations. He was duly flattered and toasted, and a glorious campaign was predicted. Gates assured him that on reaching Albany he would find 3,000 regulars ready to march, while powerful assistance was to be expected from the valiant Stark with his redoubtable Green Mountain Boys. The marquis listened with placid composure till his papers were brought him, and he felt it to be time to go. Then rising as if for a speech, while all eyes were turned upon him and breathless silence filled the room, he reminded the company that there was one toast which, in the generous excitement of the occasion, they had forgotten to drink, and he begged leave to propose the health of the commander-in-chief of the armies of the United States.

Lafayette’s toastThe deep silence became still deeper. None dared refuse the toast, “but some merely raised their glasses to their lips, while others cautiously put them down untasted.” With the politest of bows and a scarcely perceptible shrug of the shoulder, the new commander of the northern army left the room, and mounted his horse to start for his headquarters at Albany.

Absurdity of the schemeWhen he got there, he found neither troops, supplies, nor equipments in readiness. Of the army to which Burgoyne had surrendered, the militia had long since gone home, while most of the regulars had been withdrawn to Valley Forge or the highlands of the Hudson. Instead of 3,000 regulars which Gates had promised, barely 1,200 could be found, and these were in no wise clothed or equipped for a winter march through the wilderness. Between carousing and backbiting, the new Board of War had no time left to attend to its duties. Not an inch of the country but was known to Schuyler, Lincoln, and Arnold, and they assured Lafayette that an invasion of Canada, under the circumstances, would be worthy of Don Quixote. In view of the French alliance, moreover, the conquest of Canada had even ceased to seem desirable to the Americans; for when peace should be concluded the French might insist upon retaining it, in compensation for their services. The men of New England greatly preferred Great Britain to France as a neighbour, and accordingly Stark, with his formidable Green Mountain Boys, felt no interest whatever in the enterprise, and not a dozen volunteers could be got together for love or money.

Downfall of the cabalThe fiasco was so complete, and the scheme itself so emphatically condemned by public opinion, that Congress awoke from its infatuation. Lafayette and Kalb were glad to return to Valley Forge. Conway, who stayed behind, became indignant with Congress over some fancied slight, and sent a conditional threat of resignation, which, to his unspeakable amazement, was accepted unconditionally. In vain he urged that he had not meant exactly what he said, having lost the nice use of English during his long stay in France. His entreaties and objurgations fell upon deaf ears. In Congress the day of the cabal was over. Mifflin and Gates were removed from the Board of War. The latter was sent to take charge of the forts on the Hudson, and cautioned against forgetting that he was to report to the commander-in-chief. The cabal and its deeds having become the subject of common gossip, such friends as it had mustered now began stoutly to deny their connection with it. Conway himself was dangerously wounded a few months afterward in a duel with General Cadwallader, and, believing himself to be on his deathbed, he wrote a very humble letter to Washington, expressing his sincere grief for having ever done or said anything with intent to injure so great and good a man. His wound proved not to be mortal, but on his recovery, finding himself generally despised and shunned, he returned to France, and American history knew him no more.

POPULAR PORTRAITS FROM BICKERSTAFF’S ALMANAC, 1778

Decline of the Continental Congress

Had Lord George Germain been privy to the secrets of the Conway cabal, his hope of wearing out the American cause would have been sensibly strengthened. There was really more danger in such intrigues than in an exhausted treasury, a half-starved army, and defeat on the field. The people felt it to be so, and the events of the winter left a stain upon the reputation of the Continental Congress from which it never fully recovered. Congress had already lost the high personal consideration to which it was entitled at the outset. Such men as Franklin, Washington, Jefferson, Henry, Jay, and Rutledge were now serving in other capacities. The legislatures of the several states afforded a more promising career for able men than the Continental Congress, which had neither courts nor magistrates, nor any recognized position of sovereignty. The meetings of Congress were often attended by no more than ten or twelve members. Curious symptoms were visible which seemed to show that the sentiment of union between the states was weaker than it had been two years before. Instead of the phrase “people of the United States,” one begins, in 1778, to hear of “inhabitants of these Confederated States.” In the absence of any central sovereignty which could serve as the symbol of union, it began to be feared that the new nation might after all be conquered through its lack of political cohesion. Such fears came to cloud the rejoicings over the victory of Saratoga, as, at the end of 1777, the Continental Congress began visibly to lose its place in public esteem, and sink, step by step, into the utter degradation and impotence which was to overwhelm it before another ten years should have expired.