полная версия

полная версияThe American Revolution

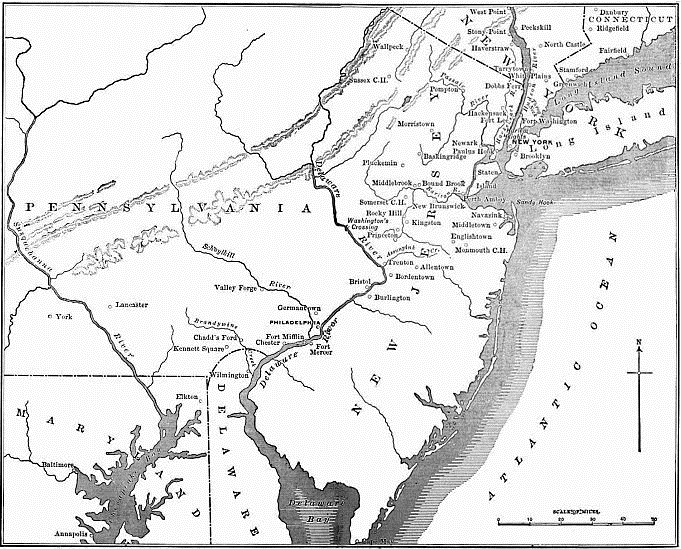

By this movement to White Plains, Washington had foiled Howe’s attempt to get in his rear, and the British general decided to try the effect of an attack in front. On the 28th of October he succeeded in storming an outpost at Chatterton Hill, losing 229 lives, while the Americans lost 140. But this affair, which is sometimes known as the battle of White Plains, seems to have discouraged Howe. Before renewing the attack he waited three days, thinking perhaps of Bunker Hill; and on the last night of October, Washington fell back upon North Castle, where he took a position so strong that it was useless to think of assailing him. Howe then changed his plans entirely, and moved down the east bank of the Hudson to Dobb’s Ferry, whence he could either attack Fort Washington or cross into New Jersey and advance upon Philadelphia, the “rebel capital.” The purpose of this change was to entice Washington from his unassailable position.

Washington’s orders in view of the emergencyTo meet this new movement, Washington threw his advance of 5,000 men, under Putnam, into New Jersey, where they encamped near Hackensack; he sent Heath up to Peekskill, with 3,000 men, to guard the entrance to the Highlands; and he left Lee at North Castle, with 7,000 men, and ordered him to coöperate with him promptly in whatever direction, as soon as the nature of Howe’s plans should become apparent. As Forts Washington and Lee detained a large force in garrison, while they had shown themselves unable to prevent ships from passing up the river, there was no longer any use in holding them. Nay, they had now become dangerous, as traps in which the garrisons and stores might be suddenly surrounded and captured. Washington accordingly resolved to evacuate them both, while, to allay the fears of Congress in the event of a descent from Canada, he ordered Heath to fortify the much more important position at West Point.

Congress meddles with the situation and muddles itHad Washington’s orders been obeyed and his plans carried out, history might still have recorded a retreat through “the Jerseys,” but how different a retreat from that which was now about to take place! The officious interference of Congress, a venial error of judgment on the part of Greene, and gross insubordination on the part of Lee, occurring all together at this critical moment, brought about the greatest disaster of the war, and came within an ace of overwhelming the American cause in total and irretrievable ruin. Washington instructed Greene, who now commanded both fortresses, to withdraw the garrison and stores from Fort Washington, and to make arrangements for evacuating Fort Lee also. At the same time he did not give a positive order, but left the matter somewhat within Greene’s discretion, in case military circumstances of an unforeseen kind should arise. Then, while Washington had gone up to reconnoitre the site for the new fortress at West Point, there came a special order from Congress that Fort Washington should not be abandoned save under direst extremity. If Greene had thoroughly grasped Washington’s view of the case, he would have disregarded this conditional order, for there could hardly be a worse extremity than that which the sudden capture of the fortress would entail. But Greene’s mind was not quite clear; he believed that the fort could be held, and he did not like to take the responsibility of disregarding a message from Congress. In this dilemma he did the worst thing possible: he reinforced the doomed garrison, and awaited Washington’s return.

REMAINS OF FORT WASHINGTON, NEW YORK, 1856

Howe takes Fort Washington by storm, Nov. 16

When the commander-in-chief returned, on the 14th, he learned with dismay that nothing had been done. But it was now too late to mend matters, for that very night several British vessels passed up between the forts, and the next day Howe appeared before Fort Washington with an overwhelming force, and told Colonel Magaw, the officer in charge, that if he did not immediately surrender the whole garrison would be put to the sword. Magaw replied that if Howe wanted his fort he must come and take it. On the 16th, after a sharp struggle, in which the Americans fought with desperate gallantry though they were outnumbered more than five to one, the works were carried, and the whole garrison was captured. The victory cost the British more than 500 men in killed and wounded. The Americans, fighting behind their works, lost but 150; but they surrendered 3,000 of the best troops in their half-trained army, together with an immense quantity of artillery and small arms. It was not in General Howe’s kindly nature to carry out his savage threat of the day before; but some of the Hessians, maddened with the stubborn resistance they had encountered, began murdering their prisoners in cold blood, until they were sharply called to order. From Fort Lee, on the opposite bank of the river, Washington surveyed this woful surrender with his usual iron composure; but when it came to seeing his brave men thrown down and stabbed to death by the Hessian bayonets, his overwrought heart could bear it no longer, and he cried and sobbed like a child.

Washington and GreeneThis capture of the garrison of Fort Washington was one of the most crushing blows that befell the American arms during the whole course of the war. Washington’s campaign seemed now likely to be converted into a mere flight, and a terrible gloom overspread the whole country. The disaster was primarily due to the interference of Congress. It might have been averted by prompt and decisive action on the part of Greene. But Washington, whose clear judgment made due allowance for all the circumstances, never for a moment cast any blame upon his subordinate. The lesson was never forgotten by Greene, whose intelligence was of that high order which may indeed make a first mistake, but never makes a second. The friendship between the two generals became warmer than ever. Washington, by a sympathetic instinct, had divined from the outset the military genius that was by and by to prove scarcely inferior to his own.

GENERAL GREENE’S HEADQUARTERS, FORT LEE, NEW JERSEY

Outrageous conduct of Charles Lee

Yet worse remained behind. Washington had but 6,000 men on the Jersey side of the river, and it was now high time for Lee to come over from North Castle and join him, with the force of 7,000 that had been left under his command. On the 17th, Washington sent a positive order for him to cross the river at once; but Lee dissembled, pretended to regard the order in the light of mere advice, and stayed where he was. He occupied an impregnable position: why should he leave it, and imperil a force with which he might accomplish something memorable on his own account? By the resignation of General Ward, Lee had become the senior major-general of the Continental army, and in the event of disaster to Washington he would almost certainly become commander-in-chief. He had returned from South Carolina more arrogant and loud-voiced than ever. The northern people knew little of Moultrie, while they supposed Lee to be a great military light; and the charlatan accordingly got the whole credit of the victory, which, if his precious advice had been taken, would never have been won. Lee was called the hero of Charleston, and people began to contrast the victory of Sullivan’s Island with the recent defeats, and to draw conclusions very disparaging to Washington. From the beginning Lee had felt personally aggrieved at not being appointed to the chief command, and now he seemed to see a fair chance of ruining his hated rival. Should he come to the head of the army in a moment of dire disaster to the Americans, it would be so much the better, for it would be likely to open negotiations with Lord Howe, and Lee loved to chaffer and intrigue much better than to fight. So he spent his time in endeavouring, by insidious letters and lying whispers, to nourish the feeling of disaffection toward Washington, while he refused to send a single regiment to his assistance. Thus, through the villainy of this traitor in the camp, Washington actually lost more men, so far as their present use was concerned at this most critical moment, than he had been deprived of by all the blows which the enemy had dealt him since the beginning of the campaign.

Greene barely escapes from Fort Lee, Nov. 20On the night of the 19th, Howe threw 5,000 men across the river, about five miles above Fort Lee, and with this force Lord Cornwallis marched rapidly down upon that stronghold. The place had become untenable, and it was with some difficulty that a repetition of the catastrophe of Fort Washington was avoided. Greene had barely time, with his 2,000 men, to gain the bridge over the Hackensack and join the main army, leaving behind all his cannon, tents, blankets, and eatables. The position now occupied by the main army, between the Hackensack and Passaic rivers, was an unsafe one, in view of the great superiority of the enemy in numbers. A strong British force, coming down upon Washington from the north, might compel him to surrender or to fight at a great disadvantage.

To avoid this danger, on the 21st he crossed the Passaic and marched southwestward to Newark, where he stayed five days; and every day he sent a messenger to Lee, urging him to make all possible haste in bringing over his half of the army, that they might be able to confront the enemy on something like equal terms. Nothing could have been more explicit or more peremptory than Washington’s orders; but Lee affected to misunderstand them, sent excuses, raised objections, paltered, argued, prevaricated, and lied, and so contrived to stay where he was until the first of December.

Lee intrigues against WashingtonTo Washington he pretended that his moving was beset by “obstacles,” the nature of which he would explain as soon as they should meet. But to James Bowdoin, president of the executive council of Massachusetts, he wrote at the same time declaring that his own army and that under Washington “must rest each on its own bottom.” He assumed command over Heath, who had been left to guard the Highlands, and ordered him to send 2,000 troops to himself; but that officer very properly refused to depart from the instructions which the commander-in-chief had left with him. To various members of Congress Lee told the falsehood that if his advice had only been heeded, Fort Washington would have been evacuated ere it was too late; and he wrote to Dr. Rush, wondering whether any of the members of Congress had ever studied Roman history, and suggesting that he might do great things if he could only be made Dictator for one week.

Washington retreats into PennsylvaniaMeanwhile Washington, unable to risk a battle, was rapidly retreating through New Jersey. On the 28th of November Cornwallis advanced upon Newark, and Washington fell back upon New Brunswick. On the first of December, as Cornwallis reached the latter place, Washington broke down the bridge over the Raritan, and continued his retreat to Princeton. The terms of service for which his troops had been enlisted were now beginning to expire, and so great was the discouragement wrought by the accumulation of disasters which had befallen the army since the battle of Long Island that many of the soldiers lost heart in their work. Homesickness began to prevail, especially among the New England troops, and as their terms expired it was difficult to persuade them to reënlist. Under these circumstances the army dwindled fast, until, by the time he reached Princeton, Washington had but 3,000 men remaining at his disposal. The only thing to be done was to put the broad stream of the Delaware between himself and the enemy, and this he accomplished by the 8th, carrying over all his guns and stores, and seizing or destroying every boat that could be found on that great river for many miles in either direction. When the British arrived, on the evening of the same day, they found it impossible to cross. Cornwallis was eager to collect a flotilla of boats as soon as practicable, and push on to Philadelphia, but Howe, who had just joined him, thought it hardly worth while to take so much trouble, as the river would be sure to freeze over before many days. So the army was posted – with front somewhat too far extended – along the east bank, with its centre at Trenton, under Colonel Rahl; and while they waited for that “snap” of intensely cold weather, which in this climate seldom fails to come on within a few days of Christmas, Howe and Cornwallis both went back to New York.

Reinforcements come from SchuylerMeanwhile, on the 2d of December, Lee had at last crossed the Hudson with a force diminished to 4,000 men, and had proceeded by slow marches as far as Morristown. Further reinforcements were at hand. General Schuyler, in command of the army which had retreated the last summer from Canada, was guarding the forts on Lake Champlain; and as these appeared to be safe for the present, he detached seven regiments to go to the aid of Washington. As soon as Lee heard of the arrival of three of these regiments at Peekskill, he ordered them to join him at Morristown. As the other four, under General Gates, were making their way through northern New Jersey, doubts arose as to where they should find Washington in the course of his swift retreat. Gates sent his aid, Major Wilkinson, forward for instructions, and he, learning that Washington had withdrawn into Pennsylvania, reported to Lee at Morristown, as second in command.

OPERATIONS IN NEW YORK AND NEW JERSEY, 1776 AND 1777

Fortunately for the Americans, the British capture Charles Lee, Dec. 13

Lee had left his army in charge of Sullivan, and had foolishly taken up his quarters at an unguarded tavern about four miles from the town, where Wilkinson found him in bed on the morning of the 13th. After breakfast Lee wrote a confidential letter to Gates, as to a kindred spirit from whom he might expect to get sympathy. Terrible had been the consequences of the disaster at Fort Washington. “There never was so damned a stroke,” said the letter. “Entre nous, a certain great man is most damnably deficient. He has thrown me into a situation where I have my choice of difficulties. If I stay in this province I risk myself and army, and if I do not stay the province is lost forever… Our counsels have been weak to the last degree. As to yourself, if you think you can be in time to aid the general, I would have you by all means go. You will at least save your army… Adieu, my dear friend. God bless you.” Hardly had he signed his name to this scandalous document when Wilkinson, who was standing at the window, exclaimed that the British were upon them. Sure enough. A Tory in the neighbourhood, discerning the golden opportunity, had galloped eighteen miles to the British lines, and returned with a party of thirty dragoons, who surrounded the house and captured the vainglorious schemer before he had time to collect his senses. Bareheaded, and dressed only in a flannel gown and slippers, he was mounted on Wilkinson’s horse, which stood waiting at the door, and was carried off, amid much mirth and exultation, to the British camp. Crest-fallen and bewildered, he expressed a craven hope that his life might be spared, but was playfully reminded that he would very likely be summarily dealt with as a deserter from the British army; and with this scant comfort he was fain to content himself for some weeks to come.

The times that tried men’s soulsThe capture of General Lee was reckoned by the people as one more in the list of dire catastrophes which made the present season the darkest moment in the whole course of the war. Had they known all that we know now, they would have seen that the army was well rid of a worthless mischief-maker, while the history of the war had gained a curiously picturesque episode. Apart from this incident there was cause enough for the gloom which now overspread the whole country. Washington had been forced to seek shelter behind the Delaware with a handful of men, whose terms of service were soon to expire, and another fortnight might easily witness the utter dispersal of this poor little army. At Philadelphia, where Putnam was now in command, there was a general panic, and people began hiding their valuables and moving their wives and children out into the country. Congress took fright, and retired to Baltimore. At the beginning of December, Lord Howe and his brother had issued a proclamation offering pardon and protection to all citizens who within sixty days should take the oath of allegiance to the British Crown; and in the course of ten days nearly three thousand persons, many of them wealthy and of high standing in society, had availed themselves of this promise. The British soldiers and the Tories considered the contest virtually ended. General Howe was compared with Cæsar, who came, and saw, and conquered. For his brilliant successes he had been made a Knight Commander of the Bath, and New York was to become the scene of merry Christmas festivities on the occasion of his receiving the famous red ribbon. In his confidence that Washington’s strength was quite exhausted, he detached a considerable force from the army in New Jersey, and sent it, under Lord Percy, to take possession of Newport as a convenient station for British ships entering the Sound. Donop and Rahl with their Hessians and Grant with his hardy Scotchmen would now quite suffice to destroy the remnant of Washington’s army; and Cornwallis accordingly packed his portmanteaus and sent them aboard ship, intending to sail for England as soon as the fumes of the Christmas punch should be duly slept off.

Washington prepares to strike backWell might Thomas Paine declare, in the first of the series of pamphlets entitled “The Crisis,” which he now began to publish, that “these are the times that try men’s souls.” But in the midst of the general despondency there were a few brave hearts that had not yet begun to despair, and the bravest of these was Washington’s. At this awful moment the whole future of America, and of all that America signifies to the world, rested upon that single Titanic will. Cruel defeat and yet more cruel treachery, enough to have crushed the strongest, could not crush Washington. All the lion in him was aroused, and his powerful nature was aglow with passionate resolve. His keen eye already saw the elements of weakness in Howe’s too careless disposition of his forces on the east bank of the Delaware, and he had planned for his antagonist such a Christmas greeting as he little expected. Just at this moment Washington was opportunely reinforced by Sullivan and Gates, with the troops lately under Lee’s command; and with his little army thus raised to 6,000 men, he meditated such a stroke as might revive the drooping spirits of his countrymen, and confound the enemy in the very moment of his fancied triumph.

GEORGE WASHINGTON (BY TRUMBULL)

Washington’s plan was, by a sudden attack, to overwhelm the British centre at Trenton, and thus force the army to retreat upon New York. The Delaware was to be crossed in three divisions. The right wing, of 2,000 men, under Gates, was to attack Count Donop at Burlington; Ewing, with the centre, was to cross directly opposite Trenton; while Washington himself, with the left wing, was to cross nine miles above, and march down upon Trenton from the north. On Christmas Day all was ready, but the beginnings of the enterprise were not auspicious. Gates, who preferred to go and intrigue in Congress, succeeded in begging off, and started for Baltimore. Cadwalader, who took his place, tried hard to get his men and artillery across the river, but was baffled by the huge masses of floating ice, and reluctantly gave up the attempt. Ewing was so discouraged that he did not even try to cross, and both officers took it for granted that Washington must be foiled in like manner.

He crosses the DelawareBut Washington was desperately in earnest; and although at sunset, just as he had reached his crossing-place, he was informed by special messenger of the failure of Ewing and Cadwalader, he determined to go on and make the attack with the 2,500 men whom he had with him. The great blocks of ice, borne swiftly along by the powerful current, made the passage extremely dangerous, but Glover, with his skilful fishermen of Marblehead, succeeded in ferrying the little army across without the loss of a man or a gun. More than ten hours were consumed in the passage, and then there was a march of nine miles to be made in a blinding storm of snow and sleet. and pierces the British centre at Trenton, Dec. 26They pushed rapidly on in two columns, led by Greene and Sullivan respectively, drove in the enemy’s pickets at the point of the bayonet, and entered the town by different roads soon after sunrise. Washington’s guns were at once planted so as to sweep the streets, and after Colonel Rahl and seventeen of his men had been slain, the whole body of Hessians, 1,000 in number, surrendered at discretion. Of the Americans, two were frozen to death on the march, and two were killed in the action. By noon of the next day Cadwalader had crossed the river to Burlington, but no sooner had Donop heard what had happened at Trenton than he retreated by a circuitous route to Princeton, leaving behind all his sick and wounded soldiers, and all his heavy arms and baggage. Washington recrossed into Pennsylvania with his prisoners, but again advanced, and occupied Trenton on the 29th.

Cornwallis comes up to retrieve the disasterWhen the news of the catastrophe reached New York, the holiday feasting was rudely disturbed. Instead of embarking for England, Cornwallis rode post-haste to Princeton, where he found Donop throwing up earthworks. On the morning of January 2d Cornwallis advanced, with 8,000 men, upon Trenton, but his march was slow and painful. He was exposed during most of the day to a galling fire from parties of riflemen hidden in the woods by the roadside, and Greene, with a force of 600 men and two field-pieces, contrived so to harass and delay him that he did not reach Trenton till late in the afternoon. By that time Washington had withdrawn his whole force beyond the Assunpink, a small river which flows into the Delaware just south of Trenton, and had guarded the bridge and the fords by batteries admirably placed. The British made several attempts to cross, but were repulsed with some slaughter; and as their day’s work had sorely fatigued them, Cornwallis thought best to wait until to-morrow,

and thinks he has run down the “old fox”while he sent his messenger post-haste back to Princeton to bring up a force of nearly 2,000 men which he had left behind there. With this added strength he felt sure that he could force the passage of the stream above the American position, when by turning Washington’s right flank he could fold him back against the Delaware, and thus compel him to surrender. Cornwallis accordingly went to bed in high spirits. “At last we have run down the old fox,” said he, “and we will bag him in the morning.”

But Washington prepares a checkmateThe situation was indeed a very dangerous one; but when the British general called his antagonist an old fox, he did him no more than justice. In its union of slyness with audacity, the movement which Washington now executed strongly reminds one of “Stonewall” Jackson. He understood perfectly well what Cornwallis intended to do; but he knew at the same time that detachments of the British army must have been left behind at Princeton and New Brunswick to guard the stores. From the size of the army before him he rightly judged that these rear detachments must be too small to withstand his own force. By overwhelming one or both of them, he could compel Cornwallis to retreat upon New York, while he himself might take up an impregnable position on the heights about Morristown, from which he might threaten the British line and hold their whole army in check, – a most brilliant and daring scheme for a commander to entertain while in such a perilous position as Washington was that night! But the manner in which he began by extricating himself was not the least brilliant part of the manœuvre. All night long the American camp-fires were kept burning brightly, and small parties were busily engaged in throwing up intrenchments so near the Assunpink that the British sentinels could plainly hear the murmur of their voices and the thud of the spade and pickaxe. While this was going on, the whole American army marched swiftly up the south bank of the little stream, passed around Cornwallis’s left wing to his rear, and gained the road to Princeton. Toward sunrise, as the British detachment was coming down the road from Princeton to Trenton, in obedience to Cornwallis’s order, its van, under Colonel Mawhood, met the foremost column of Americans approaching, under General Mercer. As he caught sight of the Americans, Mawhood thought that they must be a party of fugitives, and hastened to intercept them; but he was soon undeceived. The Americans attacked with vigour, and a sharp fight was sustained, with varying fortunes, until Mercer was pierced by a bayonet, and his men began to fall back in some confusion.