полная версия

полная версияHistory of Embalming

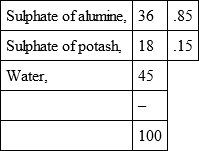

One hundred parts of this salt contains 10.86 of alumine. At the temperature of 12° centigrade, five hundred grammes of water dissolves thirty grammes of salt, from whence it results that a pound of water contains in solution only eighteen grains of alumine; from whence I have suspected that the little efficacy of alum for the preservation of animal matter, depends on the too small quantity of alumine in the solution. A fact convinced me that I was right: twenty-four hours after the immersion of a corpse in a bath containing the acid sulphate of alumine, I have observed that all the alumine was absorbed by the animal matter. Finally, the experiments which I have tried with the salts of alum, more rich in alumine, and more soluble in water, and the happy results I have attained, authorizes me to say: alum is a bad means of preservation, because it is not sufficiently soluble, and does not contain enough alumine. The reader will naturally again recur to the subject when we come to the exposition of my researches.

Sect. 3. —Means of preservation applied to each tissueIn our first paragraph, we have passed in review the different preparations which ought to precede the application of preservative means; in the second, we have seen these numerous means, and we were compelled to deliver an impartial judgment. It remains for us to explain here how anatomists have applied them to the tissues taken separately. We shall abstain from relating the preparations which precede the application of preservative means, because they are foreign to the subject which occupies us, and would uselessly prolong a discussion already too much extended.

1. Fibrous tissues.—Articulations, aponeuroses, tendons, and ligaments.– The process generally adopted is due to M. J. Cloquet, in nearly following the method employed by the tanner, he has succeeded in preserving the suppleness of these tissues.

“The following,” continues he, “is the process which I have adopted.

“Dissolve four pounds of muriate of soda and a pound of alum in ten pints of water: the articulation, which has been carefully dissected, must be allowed to macerate fifteen or twenty days in this lie; paying attention to move it frequently in the solution, to press and twist its ligaments, and, above all, to strike it lightly with a little mace of light wood. These manœuvres are intended to render them pliable, to separate the fibres, which permits the salts to penetrate more easily. Withdraw the articulation from the solution, dry it for four or five days, taking care to move it occasionally, and still to strike it with the little mace; then put the articulation into a very concentrated solution of soap, (a pound to three pints of water,) handle, and strike it again for seven or eight days, the time necessary for divesting it of salt, and permitting the soap to penetrate the ligamentous fibres, to take the place of the salts. At the end of this time, that is to say, thirty-six or forty days after the commencement of the operation, wash the articulation in a weak lie of carbonate of soda, (an ounce to two pounds of water,) after which it is to be dried.

“By this process, which may be modified in various ways, ligament may be obtained perfectly supple, of a yellowish or grayish colour, resembling chamois leather, very resisting, and permitting the joints to execute their ordinary movements.

“I have prepared, in this manner, the articulations of the shoulder, of the knee, of the fingers, and of the vertebral column. I repeated my experiments with the intention of obtaining a more expeditious method.

“The articulations may also be preserved perfectly supple, by keeping them immersed in a mixture of equal parts of olive oil and essence of turpentine.

“2. Osseous tissue.– The different preparations to which bones are subjected in order to preserve them, are maceration or ebullition, and then bleaching.

“Maceration.– When it is desired to obtain the bones very white, it is necessary to choose, as far as possible, a thin or infiltrated corpse, of an individual of from thirty to forty-five years, or thereabouts, dead of some chronic disease which has not altered the structure of the bones. Consumptive bodies are the most proper for this kind of preparation. The subject being chosen, it is roughly stripped of its muscles and periosteum; the sternum is to be detached by dividing the costal cartilages where they join the ribs; the members are to be separated from the trunk, in order that these various parts may be more conveniently placed in a trough, which is to be filled with water, and disposed in some place where the putrid emanations cannot produce any inconvenience; the bones must be constantly kept covered with water, which must be renewed every four or five days in the commencement, and at more prolonged intervals towards the end of the maceration.

“The anatomist should watch over these macerations; and it is only when all the fibrous parts separate easily from the bones, or the inter-vertebral fibro-cartilages, and the yellow ligaments separate readily from the vertebra, that the skeleton should be withdrawn from the bath and cleaned. For this purpose, he collects with care all the pieces, and places them in clean water; he cleans them by removing with a scalpel the fibrous parts which may yet adhere, and by rubbing them under water with a very coarse brush; he then places them on coarse linen to dry them.

“Ebullition.– Boiling water is often resorted to for preparing the bones of the skeleton. After having roughly separated them from the soft parts, they are placed in a kettle of water, and subjected to ebullition for six or ten hours, according to the subject. The action of the water is increased, and the fibrous parts more accurately stripped from the bones, as well as the grease, by placing in the kettle, an hour before the end of the operation, potash, or soda of commerce, (sub-carbonate of potash, and of soda,) one pound to eighty or a hundred pints of liquid. After having carefully removed the grease which swims on the surface of the water, the bones are to be withdrawn and plunged into a new alkaline lie, warm and very weak; clean them with care, as in the preceding case, separating exactly from the articular surfaces, the swollen and softened cartilages, which remain adhering to them: the bones being clean, they are to be washed frequently previously to drying.

“In employing ebullition, we have the advantage of preparing the bones more promptly, and in a manner less insalubrious than by maceration. Nevertheless, this mode of preparation has its inconvenience: 1. Bones which are boiled, become, in general, less white than those which are macerated; the blood coagulating in their pores, leaves a brown tinge, which it is often impossible to remove; 2. They commonly retain a greater quantity of medullary matter, which, by becoming rancid, soon gives them a yellow colour and a very disagreeable odour; 3. Ebullition is not applicable to the bones of young subjects, in which the epiphyses are not yet adherent; it acts upon their gelatinous texture, and despoils, in part, the short bones and the extremities of the long bones of the compact layer which envelopes them. This last inconvenience is manifested even in the bones of adults.

“Dealbation, or bleaching of bones.– In order to obtain macerated bones perfectly white, several processes are employed: 1. The best method consists in placing them upon the grass exposed to the united action of the air, the sun, and the dew, as is practised in bleaching linen, wax, &c.; care is to be taken to turn them every fifteen days, in order that they may bleach equably; two or three months of such exposure is sufficient, particularly during the spring, to give them a brilliant whiteness. 2. The bones may be exposed to the action of chlorine, either liquid or gaseous. In the first case, they are to be plunged three or four times daily in a lie which holds chlorine in solution, repeating this operation for ten or twelve days; in the second, they must be steeped in water, placed on a hurdle and covered with cere-cloth or gummed taffeta, they are then to be exposed over an earthen pan, in which has been placed suitable proportions, of muriate of soda, oxide of manganese, and sulphuric acid: from time to time this mixture is to be slightly heated. 3. In place of gaseous chlorine, the vapour of sulphuric acid may be advantageously employed, as is done in the arts of bleaching wool, silk, &c.; sulphur is slowly burned beneath the hurdle, upon which has been placed the moistened bones; the alkaline lies may also be used for the bleaching of bones although they do not appear to me so advantageous as the preceding means.

“3. Cutaneous tissues.– Deprived of grease, and of subjacent cellular tissue and exposed to the air, this tissue inclines to dry. The human skin may be prepared by the aid of several processes analogous to those of tanners and leather dressers. A lie has been recommended composed of two pounds of common salt, four ounces of sulphate of iron, and eight ounces of alum, melted in three pints of almost boiling water; the skin divested of its grease, is plunged into this solution, agitated for half an hour, and macerated for a day or two in this liquid; the lie must be frequently renewed, then the skin is to be withdrawn from the bath and dried in the shade.

“4. Cellular tissue.– Authors have successively employed desiccation, insufflation, tanning liquors and alcohol, for preparing the cellular tissue; although the method given by them as preferable, is the preservation in an aqueous solution of nitrate of alumine, to which is added a small quantity of spirits of wine.

“5. Synovial and serous tissues.– The first is much more easily preserved than the other; an accurate dissection, expulsion of the synovial liquor, kneading, and desiccation, are the means used; the operation is finished by the application of a preservative varnish. The same practice is applied to the serous tissues, but with less success; its proximity to organs eminently putrescible, such as the brain, the lungs, the liver, renders its dissolution more imminent, more difficult to prevent.

“6. Encephalon, spinal marrow, nerves.– We have already spoken of the property of nitric acid, to give consistency to the nerves, without causing them to lose any thing of their pearly whiteness. Anatomists generally avail themselves, for the preservation of the whole nervous system, of the alcoholic solution of corrosive sublimate. After twenty or thirty days immersion in the bath, these organs are withdrawn and exposed to dry. As communicating a remarkable density to the encephalic mass, a solution of sugar in brandy is much praised: it is a method recommended by Lobstein, chief of the anatomical department of the Faculty of Strasbourg.

“7. Arterial vessels, veins, and lymphatics.– The interesting details which have been furnished to us by the pamphlets of M. Dumèril on the subject of injections, will enable us to dispense with much further developments; the vessels injected and preserved, as we have seen, are dried and preserved in alcoholic liquors.

“When the object is to prepare the vessels of the bones, some care is exacted to render visible their passage through the bony frame; after having filled the vessel with a coloured injection, the piece is to be placed in a diluted mineral acid, which, in dissolving the calcareous phosphate, leaves the vessels in position, and clearly visible through the gelatinous portion of the bone.

“In causing this mucous body to dry slowly and in the shade, it will acquire the necessary transparency to manifest on its cut surface (endued with volatile oil and varnished) the distribution of the vessels which penetrate the bones. These pieces may be preserved in a collection, either in the open air, after having been plunged into an alcoholic solution of arsenical soap, which dries quickly without bleaching; and to which essence varnish adheres very well; or if the piece is small, it may be suspended in a jar of volatile oil, luted with care; in this latter case, the injection must have been made with gelatine, and not with fatty matter.

“8. Muscular tissue.– The process of Swan, or rather the discoveries of Chaussier, furnish the means of preserving the muscles by desiccation. Nevertheless, another method is recommended by authors; after having prepared the vessels and the muscles, the preparation is to be placed in a mixture of alcohol, lavender, and essence of turpentine; it is to be left for several days in this liquor, and then exposed to a warm and dry air; when desiccation is complete, a layer of varnish may be applied.

“9. The preservation of particular organs, such as the heart, the lungs, the eye, &c., differ but little from that of the organs which we have just mentioned; they are always to be either dried, or deposited in an alcohol bath. The lacrymal ways, says M. Breschet in his excellent thesis on the preservation of anatomical subjects (Paris, 1819,) are less easily preserved, although the lacrymal sac, nasal canal, the lacrymal points and conducts, offer more difficulty in their preparation than in their preservation, which may be accomplished by liquors, or by desiccation. The lacrymal canal, and its excretory canals, can only be seen on preparations in spirits of wine. Finally, the following are some passages from the same work, upon the means of preserving the embryon and the fœtal envelopes.

“It is useful to preserve the embryons and fœtuses at different periods of gestation, in order to study the successive development of each organ.

“The egg, considered in its various periods of incubation, can only be preserved in alcohol somewhat weakened, in order that it may not harden the membranes. Kirschwasser, in which has been dissolved the nitrate of alumine, forms a limpid liquor, in which the egg may be preserved without any alteration. In order to demonstrate the development of these organs, many parts may be injected; thus, during the earlier periods, the pedicle of the umbilical vesicle admits mercury, which is introduced by a small glass syringe, the tube of which has been drawn fine in the blow-pipe: this injection ought to be made on the side of the vesicle, and sometimes the metal may be seen passing into the intestines.

“The omphalo-mesenteric vessel ought also to be injected. The urachus should be opened, and its communication with the bladder should be shown on one part, and with the alantois on the other. All these parts are to be kept separate from each other, and attached by means of small pins to a plate of wax. In the fœtus, near the term of gestation, those vessels which establish the communication between it and the mother, are to be injected.

“The bones of the embryon, after having been injected, are to be placed in oil of turpentine, without its being necessary previously to place them in a weakened acid.

“As regards the envelopes of the fœtus, and the placenta which it may be intended to preserve after an accouchment at full term, injections of different colours are forced into the umbilical arteries and veins; this injection should not be too delicate, or pushed with too much force, otherwise it will pass from one of the vessels into the other. These two parts should be allowed to soak some time in an aluminous water, or, what is better, in a sublimated alcoholic solution, then place a hog’s bladder in the cavity of the membranes, blow up the bladder, and thus expose the parts to the air for desiccation; after which the bladder is to be withdrawn. The membranes, with the placenta, may thus be preserved, by placing the uterine face of the latter sometimes within sometimes without the cavity of the membranes. These same parts can be preserved in liquors. Finally, some persons make use of the method of corrosion to prepare and preserve the placenta.”

It is useless to advance here new observations; those which have been already presented on the occasion of preservation, considered in general, are equally applicable to the present. It will be perceived in the following chapter what means I propose to substitute for them, as meriting the preference.

CHAPTER VIII.

GENERAL PROCESSES FOR THE PRESERVATION OF OBJECTS OF NORMAL ANATOMY, PATHOLOGICAL ANATOMY, AND OF NATURAL HISTORY

EMBALMINGA portion of my researches has been submitted to the examination of commissioners, appointed by the Institute, and by the Academy of Medicine.

After long and repeated experiments, MM. the commissioners, have been unanimous upon the utility of the processes of preservation which I propose, and in particular my process for the preservation of subjects for the amphitheatres, the only one for which it was important for me to obtain a definite sanction, recommended by the Institute, is applied to the dissecting rooms of Clamart, with a success that every one may witness.

The faithful and complete exposition of the numerous trials which I have attempted, will furnish me, in this chapter, the occasion of indicating the most efficacious means of preservation for objects of pathological anatomy and of natural history. And, as it is incumbent on a man of study, disinterested in all that concerns science, I will give publicity to the result of my labours, the composition of the different liquids, and the mode of using them.

As for my process of embalming, I have thought that it ought to remain my property, and that one exclusively addicted to chemical studies was more qualified than the physician to subject it to those modifications which each particular case requires.

I have secured a patent of invention; for my method differs essentially enough from the preparations which I indicate for the purposes of anatomy.

It is necessary, in effect, to preserve to the tissues in embalming, a freshness and suppleness which is lost by desiccation, at the end of some months, in the subjects injected for the use of the anatomist; it is necessary, above all, to secure to the body, in this latter case, a more prolonged preservation: the facts which I can show, will prove that I have attained my end.

1. —Preservation of bodies for dissectionMy experiments upon gelatine have conducted me to the knowledge of some one of the constituent parts of different animals. I had studied the action of chemical agents habitually employed in the arts; the labour of the tanner, or leather dresser, of the parchment maker, the fabrication of glue, which I have practised on a large scale from 1819 to 1828, have equally furnished me with valuable data.

In 1826, my attention having been arrested by MM. Bègin and Serrulas, on the preservation of objects of pathological anatomy, trials were made at the Val-de-Grace.

In 1828, M. Alphonse Sanson, disposing himself to prepare a cabinet of anatomy, at the request and for the use of some English gentlemen, proposed to me to occupy myself with the question relative to preservation, which obliged me to make some researches; but it was not until 1831, and at the solicitation of M. Strauss, an anatomist of well known merit, that I undertook serious and continued labours upon the preservation of bodies. From this moment, I employed all my attention and cares to resolve this question.

The researches on the preservation of bodies demanded the re-union of different circumstances, without which it would have been impossible for me to have attained a satisfactory solution. It is easy to conceive, in effect, the great difference which ought to exist between the action of any given liquid upon some scruples of animal matter, and its action on an entire corpse; I ought to confess, also, that without the extreme courtesy of M. Orfila, who placed at my disposition, at the practical school of the faculty of medicine, all the objects of which I might stand in need, it is probable that it would have been impossible for me to have arrived at positive results. I encountered some difficulties, some resistance, and even something more, on the part of some scientific notables, and also of some ambitious subalterns; but I have surmounted all.

This work on the preservation of bodies ought only to be considered as the suit of that in which I have treated of the preservation of alimentary meats. It is only the circumstances of which I have just spoken, that have determined me to finish this work sooner.

It is well known that the study of medicine should be preceded by the study of anatomy, which teaches the knowledge of the organization of the human body; but this study is difficult and presents numerous dangers. The study of the organs exacts time; their dissection is tedious, especially if intended for demonstration. In this case it almost always happens that putrefaction seizes the subject before the preparation is finished; for, at a temperature above fifteen degrees, it is impossible to preserve a subject more than six days; under this temperature, that is to say, from 0 to 10 degrees, the longest time one can dissect is twelve or fifteen days. But the corpse always exhales mephitic miasmata before all the organs are putrefied, and this emanation of gas is certainly the cause which most frequently determines typhus fever, so destructive to a portion of our studious youths.26

Before exposing my own researches upon the preservation of bodies, it was necessary to examine the researches anterior to mine; it will have been perceived by what precedes, that they were of no service to me.

Thus, in viewing all that has been effected on this matter, I can find no indications excepting the processes employed in the arts.

In our works of chemistry applied to the arts, I have often been able to prove, practically, that muscular flesh, perfectly isolated, easily dries. When it is mixed with gelatine, it easily experiences, on the contrary, putrid fermentation. Geline27 is the animal matter, which, all circumstances being equal, putrefies the easiest; and which, forming the organs of animals, experiences an alteration more or less prompt, according to the prevalence of a greater or less quantity of water of composition present. Always, then, when we succeed in preserving from putrefaction this animal part, the other parts will be disposed to desiccation. My researches have conducted me to this conclusion.

In order to find a method of preserving bodies, and animal matters in general, it was essential to examine the action of chemical substances to which may be attributed properties which produce upon the constituent parts of these matters an immediate action; it is necessary also, that they should be easily procured, and that they be of a moderate price. I am satisfied that acids do not preserve animal matters; they disorganize them more or less promptly, in direct proportion to their concentration. Many weak acids, among others hydrochloric acid, at five degrees, may be employed to dissolve the calcareous salts from the bones; nitric acid also, at five degrees, may be brought into use in some particular cases; for example, when it is wished to study the nervous system; but then the bones are softened, the geline is in part disorganized, the muscles are discolored, and become flabby, as well as the viscera; the nerves only remain of a pearly blue, strongly pronounced.

Arsenic acid has a very marked action on animal matters; I shall make it known without delay in my second memoir upon gelatine. It preserves bodies well, but appears to favour their desiccation. In the details of experiments made under the surveillance of the commissioners of the two academies, I shall cite the effects produced by the employment of this substance. Acetic acid preserves flesh only by drying it. This acid weakened, or vinegar, retards putrefaction, softens the bones, as well as the muscles, which are discolored by its action.

Concentrated lies dissolve all animal matters; weak alkaline solutions disorganize more or less promptly the same substances.

A very small quantity of alkali suffices, when warm, to decompose very large masses of glue. This effect is often produced through ignorance in the manufacture of strong glue.

Salts only preserve meats when employed dry, or in very concentrated solutions; it is necessary that their affinity should be sufficiently great to absorb all the water of combination of animal matters. It may be then affirmed that salt only preserves meat by drying it; thus those salts more soluble in warm than in cold water; may, when injected warm, in a saturated solution, be considered as a good means of preservation, but which cannot be employed for anatomical purposes, because of the crystals which form in the organs during the cooling of the injected liquor.