полная версия

полная версияHistory of Embalming

Macerations in alkaline and etherial liquors are still of great assistance, as the researches so happily conceived and executed by Bichat have proved.

Finally, corrosions are indispensable to the removal of the parenchyma from injected preparations, when it is intended only to preserve the interior network of vessels.

The following are the attentions which this operation exacts: The injected part is consigned to a vessel of pure water for two or three days, which is occasionally to be renewed, in order the better to disgorge the vessels of any blood they may contain. It is afterwards to be solidly fixed on a piece of wax at the bottom of a porcelain vase, pierced with holes near the base, through which the liquor used to wash them may flow off without deranging the vessels. This corrosive liquor is the muriatic acid, or spirit of salt; the aquafortis of engravers, or nitric acid, may be used for the same purpose.

The first time, the preparation is to remain two or three hours in this acid, which is then drawn off and replaced by the same quantity of water, which is allowed to flow on it in small streams. This water is left for four or five days, according to the season, until the water begins to be covered with a scum, and the preparation begins to be cottony at its surface; the liquor is poured off a second time, and the pot or vase is placed beneath the cock of a fountain, from which escapes a delicate stream of water, which will carry off slowly and without shocks, any detached parts; when it is perceived that the washing carries off no more animal matter, the acid is poured into the pot, of which the opening is to be reclosed with a stopper of glass or porcelain, warmed and endued with wax. This operation is to be repeated every four or eight days, until the tunics of the vessels are altogether denuded, and the injected matter is seen throughout.20

c. Injections.– These are evacuative, repletive, antiseptic, or preservative. The first have for object, as their name indicates, to disembarrass the vessels or hollow organs, of the matters and fluids which they contain; they consist of water, of acids very much reduced, of diluted alcohol, &c. Thus it is serviceable to inject water or alcohol into the bloodvessels to prepare them for the reception of the repletive and preserving injections. The second are either definite or temporary.

The substances employed in these injections are vehicles for colouring matter. The nature of the vehicles determines that of the colours, which ought to be as far as possible, analogous to those of the humors, which the vessels contained during life.

As vehicles, those fluids which always retain their fluidity are rarely employed, for parts thus injected cannot be dissected, and they are, besides, apt to allow the colouring matters which they contain in suspension, to be deposited.

Liquids saturated with glue or gelatine, made use of in ordinary injections, have the inconvenience of not being equally solidifiable at different degrees of temperature, or harden too rapidly by cooling; they are made with the glue of commerce, either simple, or mixed with gummy or saccharine matter; that commonly used, is called Flanders glue, although it is manufactured in Paris, and that called mouth glue, which only differs from the other in containing a little gum or sugar. That which succeeds best, because it melts with the heat of the hand, and which nevertheless coagulates at a temperature of twenty-five or twenty-six degrees of Reaumer’s thermometer, which is one of the highest points to which our atmosphere attains, is made of the membranes of fishes, or icthyocolla. An ounce is to be melted in a sand-bath, in double its weight of water, and mixed afterwards with two ounces of alcohol, previously warmed. In these sorts of gelatinous injections, there is much choice in the colouring matters. All those that are ground like gum, and which are used in miniature painting, and in painting “a la gouache,”21 may be employed; they remain very well suspended.

The sticks of carmine of Delafosse, and the carmine lacks of Hubert, may then be used with advantage for the arteries; for the veins, Prussian blue, ground in vinegar, and the white of zinc of Antheaume, or that of oyster shells well porphyrized, for the colour of metallic oxide is subject to change in animal matter; they are also subject to the inconvenience of becoming precipitated by repose before the vehicle cools, and thus obstruct the smaller vessels.

Liquors which can be made solid by the effect of certain re-actives, offer, on this account, some advantage. It is thus, that it is serviceable to soak for a day or two in a solution of nut-galls or of tannin, those parts injected with gelatine, when it is intended to preserve them dry. In partial injections of lymphatic vessels, and particularly of the chyliferous, cow’s or goat’s milk, may be made use of. When, after having tied the thoracic duct, injections of milk have been made into all the vessels in which can be introduced the beak of a glass syringe, or of the syringe used for injecting the lacrymal ducts, pour on the surface of the injected parts strong vinegar, or a diluted acid, which will coagulate the milk, so that the chyliferous vessels will be found filled with a solid, white, and flexible.22

The most common, the most solid, and the most convenient injections, are made of fatty and resinous matter. Volatile oils, balsams, resins dissolved in alcohol, fats, wax, and the most ordinary fixed oils, are principally used. These different substances are combined, and the compositions of them are varied according to the nature of the injections, which it is desirable to prepare, and above all, according to the manner which it is proposed to preserve them.

The nature and the preparation of the colouring matters, ought also to vary according to the kind of fatty medium which is used.

The volatile oils being nearly equally penetrating, turpentine is generally chosen, because it is cheaper. Nevertheless, for small objects, the citron, or that of a species of lavender (aspie of the shops) is preferred, on account of their odour, which are besides not very expensive. When it is intended to inject only with one of these oils, which makes a liquid matter extremely penetrating, after having dissolved a colouring matter previously ground in a fixed oil, the mixture is slightly heated. This liquor is generally employed to render perceptible the small vessels of membranes, which are not to be dissected, but well preserved in their integrity. If it is intended to inject the large trunk which supplies these membranes towards the end of the operation, it is necessary to inject a little essence of varnish, charged with much resin, and before drying the piece, let it soak a day or two in an aqueous solution of the deuto-chloride of mercury, according to the process of Chaussier.

The matters with which the volatile oils are to be coloured, should be previously ground with the greatest care. It is easy to procure those which are prepared with nut oil, and which are sold in little bladders to be employed upon palettes.

Colours, thus prepared and intimately amalgamated with fixed oils, remain much better suspended; the heaviest oxides, even those of lead and mercury, are not then subject to become deposited.

Resins, dissolved in spirits of wine, are also sold by the pint, all prepared, under the name of varnish, and in general are not costly. Those which the anatomist can turn from the ordinary arts to his own profits, are employed principally in pieces which it is intended to preserve dry. Perfect success attends the varnish, named in the shops fat, wood-red, à la copale, and with some others which remain a long time flexible.

These fluids are difficult to colour; it is necessary, for the first, to grind the colouring matter with essence, and for the others with alcohol; and to incorporate them afterwards with varnish after having slightly heated them. The carmined lakes, thus suspended in fat varnish, produce absolutely the effect of arterial blood; this colour preserves very well, and with such like injections it is unnecessary to colour the surface of the arteries.

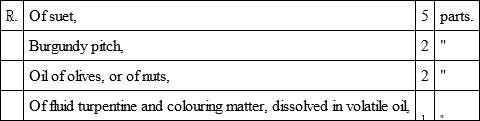

The mixture of mutton fat or of suet, of white or yellow wax, of the fixed oils of olives, nuts, or flax seed, are the ordinary matters of injections, even for those destined for corrosions. The different degrees of solidity or softness are determined by the calculated proportions of wax and oil, and by the amalgam of resinous and colouring matters.

In general, in this sort of injections it is advantageous to introduce beforehand, a small quantity of volatile oil mixed with the fatty matter which is to serve for filling the vessels; by this preliminary process a liquid more fluid, more penetrating, higher coloured, and susceptible of cooling more slowly, is driven before into the smaller ramifications.

I could here transcribe several receipts proper to indicate the proportion of fatty matters among themselves; but the season during which the pieces are made, the nature of the ingredients employed on them, will occasion the proportional quantities to vary, so that a sketch only can be given for obtaining a matter which may be made more solid or more fluid after having tried it by cooling some drops separately. Nevertheless, here is one of those receipts:

This latter part should not be mixed until the liquor is well melted and ready to be put into the syringe, as the heat will volatilize the volatile oils, which will become disengaged in the form of gas, and cause the mass to occupy a very great volume.

As a matter of injection, the dissolved gum elastic or caoutchouc may be employed; it becomes gelatinized in losing a portion of its menstruum by desiccation. After leaving this matter in a moist place, and having well washed it, in order to clean it of the clayey matter which generally impregnates it, it may be dissolved in volatile oils by heating it in a sand bath, with a moderate fire in a matrass with a long neck; adding by degrees, a sufficient quantity of oil to render the mass very fluid, incorporating with it the colouring matters which have been previously ground in an essential oil. The gum elastic may also be dissolved in ether, but this process is too expensive; and as a matter for injecting this liquor is not preferable to the other. The elastic injections are only advantageous in the preparation of parts which are not to be exposed to cutting instruments, and to which it is desirable to preserve a certain degree of suppleness, as in the injection of the cotyledons, or the placenta of women. This liquor, it must be confessed, has the great inconvenience of retaining its odour a long time, assuming its solid form with difficulty, and of rendering the preparations pitchy, and rebellious to varnish, and becoming loaded with dust.

There are certain organs which may be injected with solid matters, in order to obtain, in relief, resisting, but coarse, the forms of interior cavities. Such is the injection with the matter which forms the stucco paste, or of fine plaster diluted with gelatinous water, which gives to this salt a greater solidity when it takes its consistency. This gross matter is employed with advantage to render more solid the membranes of certain cavities, in the thickness of which it is desired to search for the nerves. Pure wax does not present the same advantage, because it exacts more heat, and contracts more by cooling, although it is more applicable in case it is proposed to corrode with acids all the fleshy or osseous parts, in order to become acquainted with the real form of their interior capacity: in fine, the fusible metallic mixture of Darcet is employed under different circumstances, but it is not more useful.23

Preservative injections, which may also be applied to vessels and to hollow organs, are composed of materials to which have been attributed preservative properties to the tissues: such are the solutions of mercurial salts, arsenical, ferruginous, &c., and different aromatic and spirituous liquors.

d. Ablutions. – These vary according to the end proposed: acids; these serve to give whiteness to some tissues and resistance to others: alkaline; these clean the preparations, divesting them of the mucilage and grease which they contain. In one word, the action of aqueous liquids, of oily, alkaline, saline, acid, alcoholic, is necessary before, as well as after dissection to preserve the preparations.

When these preparations are left a longer or shorter time in water, they are subjected to what is called a degorgement; the bath ought to be renewed until it will no longer receive any colouring matter.

The removal of grease is included under dissection, maceration, and ablution.

e. Ligature of the vessels.– This is made with a flat silk, or silk very slightly twisted, during the dissection, or immediately after, on the extremity of the vessel which contains the injection; it is necessary in order to prevent the escape of the injected matter.

f. Separation and distention of parts.– These offer the whole surface of the prepared pieces to those agents of preservation which ought to be applied to them; they sustain them, and preserve them from being deformed. Besides, it is well known, that the means of separation and distension ought to vary according to the form of the organs; atmospheric air suffices for hollow and thin organs, the stomach, the intestines, the bladder, &c. Under other circumstances, wool, hair cotton, plaster, &c., serve better.

Sect. 2. —Means of PreservationThe means of preservation may be arranged under two principal heads, as we have said, according as the anatomist intends to expose his preparations to the open air, or to preserve them from insects and render them more transparent by the aid of certain liquors, in which it is intended to keep them continually.

Preservation by desiccation.– When applied to soft parts is only applicable to anatomy, properly so called, and to natural history; it cannot be employed for specimens of pathological anatomy.

Desiccation is preceded by a more or less prolonged immersion, according to the thickness of the organs in acid or saline solutions, &c.; that which presents the greatest advantage for the nerves, according to Dumèril, is diluted nitric acid. The salts commonly employed present some inconveniences. Corrosive sublimate hardens too much, and causes the parts to contract on each other; the triple sulphate of alumine, (alum,) often chrystalizes in drying, which produces in the interior of the piece, which ought to be pellucid, saline vegetations, which not only elevate the organic lamina, often rendering the surface tuberculous, but further deprive the part of the transparency necessary to see the texture of it; the muriate of soda, (white kitchen salt,) attracts the humidity of the air, and causes the varnish to scale off, which can have no hold upon the preparation. Diluted nitric acid, with which the parts are washed, does not expose them to these inconveniences: the preparation preserves, it is true, a certain degree of suppleness; it tarnishes a little, but is never humid.

The numerous means used for disposing the preparations to desiccation, may be reported under four series:

Alcohol, where expense is no object, is preferable to all the others; its affinity for water gives it the property of absorbing humidity from anatomical pieces.

The deuto-chloride of mercury, the proto-nitrate of the same base, the solutions of acetate of lead, and of the proto-nitrate, merit the preference among metallic substances.

Marine salt and alum are nearly those alone among the earthy salts which have been employed for this object. M. Breschet advises that, according to the method followed by the tanners, the piece be permitted to remain for several days in powdered sea salt, and to immerge it afterwards in a strong solution of alum for fifteen days, when it is to be withdrawn and dried.

In fine, tanning is still a preparatory method for desiccation.

Desiccation.– Anatomical pieces may, says M. Doct. Patissier, be dried in the open air, in a stove, in a vacuum, and by employing substances very avaricious of water, and in a bath of sand, or of absorbing powders; but desiccation by means of an oven is the best process: the heat of the oven must be neither too weak nor too strong; the most convenient temperature is that of 45° to 55° of centigrade.

When the parts have been dried by one of the processes just mentioned, if they be abandoned to themselves, they would become injured in a little time by humidity and insects. There remains, then, some care to be taken before depositing them in a cabinet; they should be washed in a liquid containing a preparation of arsenic, or of sublimate, or rather by applying to them a varnish containing one or both of these substances. We shall not reconsider here the compositions of varnishes, having already given several formulæ for them when speaking of Swan’s method, and we shall have occasion to refer to them again when passing in review the different methods of preparing objects of natural history.

Preservation in liquids.– Anatomical parts are also preserved, and more advantageously, in liquids. We shall now consider the acids, or acidulated waters, alkalies, salts, oils, spirituous or alcoholic liquors; expose their advantages under certain circumstances, their inconveniences under others.

When acids are employed for preserving anatomical parts in their natural state of suppleness, caution must be used to dilute them, with a sufficient quantity of water, so that they may not corrode or harden the parts. In general, it is advantageous to allow them to remain for the first few days, in a very weak acid, and not place them in the prepared liquor, until they have ceased to make any deposit. The objections against muriatic acid are, that it renders the surface of the parts gelatinous, gluey, and transparent; of nitric acid, to tarnish and contract them; of sulphuric acid, to bleach them. All these acids decompose the parts when they are not sufficiently diluted with water; they allow the liquor to putrefy or to freeze, and break the vessel when they are too weak. The proportions are indicated by experience, and depend upon the nature of the part which it is intended to preserve. It is those parts in particular which are loaded with fat, that are best preserved in acid liquors.

In general, little use is made of liquors which hold alkalies in solution: the carbonates of commerce are preferable; and these are used with advantage, when it is necessary to keep for several days, before dissection, animal parts in which corruption has already commenced.

Those salts derived from the combination of acids and earths, the alkalies or metals, may be employed like the acids diluted with water. They are not subject to the same objections. The nitrate of potash, the muriate of ammonia, those of lime, or of soda, are very proper for preserving pieces of myology; they appear even to reclaim the red colour of the muscles, when these solutions are strongly saturated; but, then, they are liable, some of them, to liquify, others, to effervesce or to chrystalize upon the sides of the jars, and even on the surface of the parts themselves, which is a very great inconvenience when it is wished to expose the parts to view.

The solution of the triple sulphate of alumine, (alum of commerce) is employed with the same advantages; it must be confessed, however, that they are more proper to preserve membranous parts which have been previously allowed to macerate a long time. In general, this liquor discolours the parts, and deposits at length on the sides of the jar and the surface of the piece which it bleaches, the white earthy matter with which it is charged; this is a great objection, and exacts great care when the atmosphere freezes suddenly.

Chaussier has latterly proposed the solution of the deuto-chloride of mercury, in distilled water. This liquor is very useful, but it bleaches the surface of the parts, particularly the muscles; it hardens, and attacks the instruments when new researches are attempted, upon parts already prepared. This discovery, however, is very valuable to obtain the mummification of certain parts, which it is intended to preserve in the open air. In order to obtain a solution always equally saturated, Chaussier,24 has proposed to keep at the bottom of the liquor two or three knots of fine linen enclosing a certain quantity of this metallic salt, in order that the saturation may always be complete.

In general, we repeat, these preservative liquors are attended with the great inconvenience of leaving suspended, after frosts, the albuminous matters which the cooling has caused to precipitate; so that the fluid of the vessel which contains the preparation becomes clouded, and no longer permits the object so be clearly seen. Besides, the liquor freezes, and breaks the jar, when the temperature is very low.

The volatile oils, from whatever vegetable they may have been extracted, are very proper for the preservation of anatomical objects; they lose at length, it is true, their transparency; they thicken, precipitate to the bottom of the vessel, the animal fluids which exude from the object, which exposes them to corruption. But all these changes are sensible to the eye, and the fault is easily repaired when perceived in time to renew the liquor, which may be afterwards re-distilled.

It is never useful to employ these liquids for the preservation of objects loaded with fat, for they dissolve these at length and penetrate them entirely, changing their form and colour.

Volatile oils, and particularly turpentine, which is the best, are employed to preserve with the greatest success certain injections, the vehicles of which would be dissolved in alcohol, and all the parts whose vessels have been injected with coloured gelatine; finally, these oils are used in all cases where it is desirable to preserve the transparency of certain membranes, which have been previously dried.

Alcoholic liquors are most generally used for the preservation of animal substances, if they are more costly, they are liable to fewer objections. Brandy, rum, tafea, are coloured by a resinous substance, which clouds their transparency, and which is liable to be deposited. The alcohol of cherries, of grain, of cider, or of wine, is preferred at present, which can be procured well rectified and transparent, and which may be afterwards weakened with distilled water, so as to obtain alcohol very limpid, marking from 22° to 30° of Baumè’s areometer.

Some years since, alcohol was still employed, in which was dissolved certain transparent resins; such as camphor, but it has since been ascertained, that animal substances which have remained in this liquor, contract such a disagreeable and nauseous odour, that it becomes very painful to keep them long uncovered for examination, consequently, pure alcohol is preferred.

Nevertheless, when it is desirable to preserve the preparations of the nerves, it is better to put a few drops of muriatic acid into the jar along with the spirits of wine: this mixture bleaches and renders more visible the nervous fibres, on which the acid appears to act more specially. The yellow tinge, which the parts sometimes assume in the end, may sometimes be removed by pouring a small quantity of muriatic acid into the jar which contains them: this precaution occasionally gives a new aspect to the parts.

We have chosen this passage of M. Dumèril’s pamphlet, because it gives with sufficient accuracy all the liquids employed by preparors, and because it indicates a part of the inconveniences which we have experienced from them.

We shall see to what extent the more recent additions made to sublimated alcohol, of hydrochlorate of soda, (chloride of sodium,) of the hydrochlorate of ammonia, of the muriate and nitrate of alumine, can contribute to the wants of the collector of pathological anatomy.

Before entering into this critical examination, it remains for us to describe the processes employed by naturalists for preserving the different species of animals. The excellent manual of M. Boitard, so useful to preparors, will furnish us with this information.