полная версия

полная версияHistory of Embalming

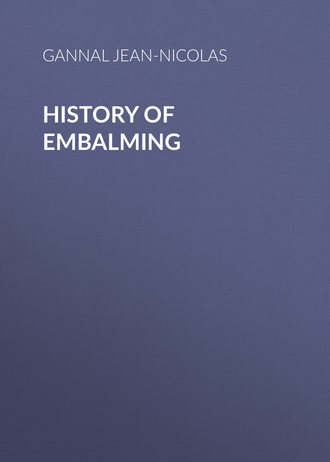

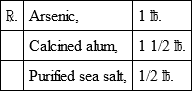

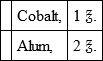

Means of preparing and preserving practised by naturalists.– The soap of Bècoeur enjoys with naturalists a great reputation as a preservative. It is this preservative, then, that we should recommend as the most approved by experience: the following is the receipt:

In the original, four ounces of lime is recommended, and we have given this dose in our first edition; but it has since been found by doubling it, the preservative is less pasty, and less difficult to use, more abundant and equally good.

M. Simon thus composes the preservative, but he adds to it a certain quantity of corrosive sublimate, and of camphor dissolved in spirits of wine. The camphor, thus incorporated with the preservative, does not volatilize so easily as when used in powder.

When used, a sufficient quantity is placed in a small vessel, and, with the aid of a hair pencil, it is moistened with water and spread upon the piece to be preserved.

Some naturalists, fearful of the danger of the daily use of arsenic, have endeavoured to replace this preservative by another composition, but have never succeeded in obtaining results equally advantageous; but, nevertheless, in order to render this work as complete as possible, and to facilitate new researches, we thought that we should at least, indicate here, the different processes which have by turns been imagined.

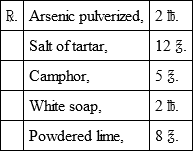

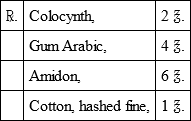

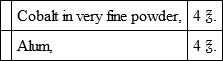

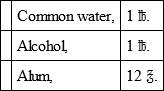

In my cabinet of natural history, I have indicated, under the name of soapy pomatum, the following composition:

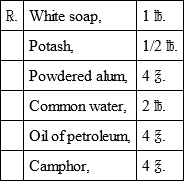

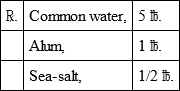

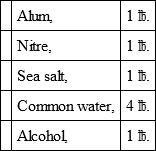

M. Mouton de Fontenille proposes a tanning liquor thus composed:

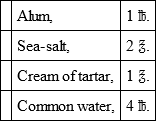

Boil the whole, except the alum, which is not to be added to the liquor until withdrawn from the fire; it is to be put into a well corked vial for use.

M. Mouton thus uses his liquor: when an animal is skinned, and the skin divested of grease as well as possible, the internal surface is to be moistened with the tanning liquor until it is perfectly impregnated; if it be a dry skin, it is to be moistened in the same manner until it is softened.

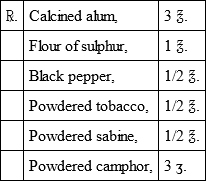

An author has recommended, under the name of antiseptic powder, the following composition:

The whole to be reduced to a fine powder and well mixed.

We advise that powdered arsenic never be used, because, by volatilizing, it might penetrate the lungs and cause mortal ravages.25

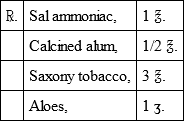

The preparor Nicholas recommends, in certain cases, a composition which ought to be here mentioned, not to advise the use of it, on the contrary, to advise the rejection of it; for far from driving off the insects, it attracts them; he calls it gummy paste.

Other preparors, without passing any thing over the skin, confine themselves to the use of the following powder:

The whole to be finely powdered and well mixed.

Some amateurs content themselves in passing over the internal surface of the skin they wish to preserve, a good layer of melted suet mixed with a small quantity of corrosive sublimate; it appears that they have obtained some advantageous results, which authorises further experiments; it has been remarked, that suet is never attacked by insects; perhaps, if it were combined with some mineral matter less dangerous than the sublimate, results as satisfactory as those from the arsenical soap of Bècoeur might be obtained.

Such are the preservatives which have been employed in France, but which do not possess, to any extent, the efficacy of the arsenical soap of Bècoeur. It appears that the Germans employ others to which they attribute the same qualities, which appears to us very doubtful in all cases: they may be mentioned here.

Naumann, in the first place, gives a method which appears to us vicious, although he invokes in its favour his own experience. After having said that the best method of preserving is to close hermetically, stuffed animals in boxes, he adds: “I do no more for skins which are to travel in boxes, than powder them with the following composition:

“Of lime decomposed in the air, and finely sifted, two parts; of saxony tobacco, also sifted, one part.”

Hoffman approves of, and recommends the following powder:

The librarian of Jena, M. Theodore Thon, proposes the following powder, as better for preserving animals in the open air.

To be powdered and mixed. Before employing this powder, give a layer of essence of pine, (turpentine,) in order that it may adhere better to the interior of the skin. If the latter be very greasy, add an ounce and a half of lime decomposed in the air and sifted.

Among the preservatives which this naturalist has investigated, we find a very simple one, which he says, is very effectual for mammifera: the following is its composition:

The same naturalist recommends another composition as very good, and which I think would be worth making a trial of for large animals, which would be very expensive done with arsenical soap. Very fat bitumen is to be melted, in a strong solution of soap-water, until the whole forms a sort of clear broth; the interior of the skin is to be endued with this mixture, which costs very little.

Preservatives in LiquorsLiquors are employed in baths, in lotion, in friction, in injection, and finally, in permanent baths, in which certain objects are always to remain; we shall now treat of these four methods of preservation.

Of the BathIn many animals, and particularly in the mammifera, the skin has such a thickness, such a degree of intensity, that the arsenical soap can not penetrate it sufficiently in order to preserve it perfectly; it is then that the bath becomes an indispensable operation. In penetrating the skin which is left to macerate a longer or shorter time, the preservative molecules with which it is saturated enters all its pores, and preserves it for ever from the attacks of insects.

The following is the composition of the bath employed by the naturalists – preparors of Paris.

This mixture must be boiled until it is all entirely dissolved, and when the liquor has cooled, plunge the skins into it; those of the size of a hare, or thereabouts, need not remain longer than twenty-four hours; those of the larger animals must macerate a longer or shorter time, according to their thickness; from eight to fifteen days would not be too long for a buffalo or a zebra. At the museum of Natural History of Paris, they very rarely make use of this composition; they are satisfied to macerate the skins in spirits of wine, which they keep in hogsheads for that purpose. Without attempting to criticise this method, which may have its advantages, we think that they might, perhaps, in this particular, follow the English naturalists, and add, like them, a small quantity of corrosive sublimate dissolved in spirits of wine.

Nevertheless, as we ought to be impartial, we should mention here the dangers attendant on the use of this terrible mineral, so much boasted by Sir S. Smith, president of the Linnean Society of London. When there is occasion to mount a subject prepared with sublimate, whether it has been employed in powder or in solution, in arranging the animal there arises a dust, which penetrates the nostrils, and may cause serious accidents. Arsenic, though much less energetic, is not even free from this inconvenience. Thus it is only with much precaution that preparors should handle preparations in skins which they receive from foreign countries, the substances used in the preparation of which they are ignorant.

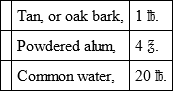

Let us now pass to the other preservatives in liquor, less generally employed, at the present time, although some of them may be very useful. The following is the tanning liquor which I have proposed in the Cabinet of Natural History:

An ancient author, the Abbe Manesse, composed his bath in the following manner:

When an animal has been mounted or prepared, and fears exist less the insect should attack it, this may be prevented by washing its feathers, its hairs, or its naked skin, with one of the liquors which we are about to indicate. Animals exposed to the open air have, above all, need of being thus treated, and yet, by an inconceivable negligence, many amateurs permit their collections to be devoured, for the want of employment of a means both simple and easy.

1. The essence of wild thyme, has been recently advantageously employed; in using it the feathers or hairs of an animal are to be raised every little distance by a long needle, and at their bases, that is to say, the skin, is to be touched by means of a hair pencil with a drop or two of the essence, and when this has been well imbibed, the hairs or feathers are to be replaced, their extremities, never being in contact with the liquor, cannot become tarnished.

2. Essence of turpentine has been recommended by almost all authors, and yet, when made use of it is perceived with astonishment that great inconveniences result; it never dries upon the feathers, which it greases and soils in spite of every precaution, the spots spreading and enlarging like oil; besides this, it forms a species of glue, which arrests and fixes the dust in such a manner that no subsequent effort can remove.

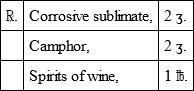

3. Liquor of Sir S. Smith.– This intelligent English naturalist, president of the Linnean Society of London, having turned his attention to the preservation of prepared objects, already classed in collections, has concluded that there cannot be a more efficacious means employed than the following liquor.

In large animals it is applied by means of a sponge, which is passed at different times over the whole exterior of the animal, until it is perfectly impregnated, and the liquor has penetrated to the skin. In small animals a hair pencil is used, and the operation is performed in the same manner. Whether the individual submitted to this practice be recently prepared, or whether it has long remained in a collection, it must be permitted to dry perfectly before placing it in a cabinet.

In France this dangerous composition is replaced by the preservative in very small quantities diluted with water.

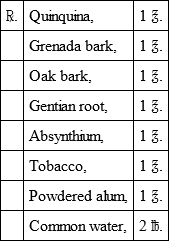

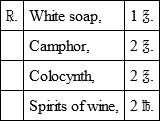

4. The bitter spirituous liquor, recommended by other authors, is thus composed:

The whole is to be subjected to cold infusion for several days in a vessel hermetically sealed, frequently shaking the vessel during this interval, and allowed to strain through unglazed gray paper; when it is thought that the infusion is done, it must be put into bottles equally well corked, and used after the same manner as the preceding.

5. Varnish is employed only on the naked skin of reptiles and fishes, to which it restores a portion of its splendour; it must be absolutely colourless, and perfectly transparent. In order to obtain it thus, it must be prepared by dissolving fine and new turpentine in spirits of wine, which must themselves possess the qualities above mentioned. It is to be applied with a pencil of squirrel’s tail, or the tail of a martin, and the object is left exposed to the air, sheltered from the dust, if it be wished to hasten its desiccation.

Liquors employed in InjectionsInjections are more generally employed for the preparation of the eggs of birds, for which it is desirable to secure a long preservation; although by a very bad method, they have also been used for the desiccation of very small animals.

In order to decompose the flesh of a fœtus already formed in an egg, recourse is had to a strong solution of a fixed alkali, of soda, of tartar, or to ether.

Liquors, in which objects are preserved which do not admit of dryingThe qualities which a liquor ought to possess, in which objects of natural history are placed, are, independently of that of preserving from decomposition: 1. to be colourless, that they may not tarnish the contained objects; 2. not to attack by corrosion the proper colours of the object; 3. to be perfectly transparent, that the contained objects may be visible through the vase which encloses them; 4. the power to resist frost, in order that they may not break the jar which holds them.

1. Spirits of wine, of from fourteen to eighteen degrees of the areometer of Baume, appears to be the liquor which best fulfils all these conditions; the other alcohols, such as those from potato, from grain, from sugar, &c., have the same qualities; but a serious inconvenience is the high price of all of them, and this reason alone is an inducement to look for other compound liquors, capable of replacing them with more or less advantage.

2. Nicholas recommends the following composition:

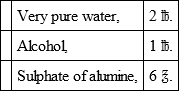

The English naturalist, George Graves, in a work published in London, seven years ago, indicates a liquor which has much analogy with the preceding:

The following is the method of preparing this mixture: the alum is pulverised and put into a vessel capable of resisting heat; water being heated to ebullition is poured upon the alum; when cool, it is to be filtered through gray paper, and then mixed with alcohol. The same author recommends another liquor, thus composed, but of which the mixture is made cold.

4. The Abbe Manesse, after various trials, more or less successful, has published the result of his experiments; he proposes as the best liquor, one composed as follows:

The water used should be distilled, so as to be freed of any foreign matter; the alum should be the most transparent that could be obtained, and the salt also should be purified before use. The liquor may be made cold, but it is always better to boil it, with the precaution not to add the spirits of wine until it has cooled.

All these liquors are inferior to spirits of wine, inasmuch as they are liable to freeze.

After having given this long list of the known means of preserving, and given in detail the representation of authors, it remains for us to judge of them, to determine their merit, and the degree of confidence that ought to be accorded to each, under the triple point of view of the preservation of objects of normal anatomy, of pathological anatomy, and of natural history.

1. Process of desiccation.– It can be of no utility for pathological anatomy, because it changes entirely the aspect and texture of parts, and in most cases it leaves no traces of the alterations which it is important to know. For normal anatomy, these preparations are, and always must be, from the simple fact of desiccation, a feeble resource, and really much inferior to the artificial subjects of M. Azoux; for this ingenious preparation, if it has many of the faults of dry anatomy, the objects are not so deformed as scarcely to be recognised.

Further, each of the preparations which tend to desiccation has its particular inconvenience: thus those of the deuto-chloride are numerous, as we have seen in the preceding chapter, and as have remarked in this the authors whom we have cited. We may add that the salts of mercury, of copper, and of lead, which, in combining with gelatine, form, it is true, an inalterable compound, have a great affinity for hydrosulphuric acid, and that there results from this affinity, a necessary deterioration of the objects, colouring them black. Sea salt does not possess durable preservative properties; and its affinity for water even facilitates the decomposition of the dried subjects which contain it. Alcohol is, doubtless, a good means, but it requires to be frequently renewed, until by its affinity for water it absorbs all which the organs contain; but alcohol costs forty cents a quart, and loses always by evaporation. Besides, parts thus prepared, are not less deformed than other dried parts, when subjected to desiccation.

The naturalist finds in the soap of Bècoeur, in other preparations containing arsenic, the deuto-chloride of mercury, alum, &c., sufficiently good means of drying or of tanning the skin and other animal tissues. But, as M. Boitard has remarked, these preparations are not without their inconveniences.

What have I to offer the anatomist who believes in the utility of dried preparations, to the naturalist whom a real necessity often forces to recur to them? My liquid, employed as a bath or injection, without either danger or inconvenience, and which costs only two or four cents the quart.

I shall give here an example of injection; a corpse is injected by the carotid with from five to seven quarts of the acetate of alumine at 20°, and containing in solution about two ounces (fifty grammes) of arsenic acid. Four days after this injection, if it is intended to prepare the large and small vessels, inject by the aorta half a quart of a mixture, equal parts, of the essence of turpentine and essence of varnish; finally, make a single cast of a hot injection of a mixture of suet and of rosin, in equal parts, coloured with cinabar for the arteries, and with a black or blue colour for the veins. Then, the corpse, or the part of the corpse which it is intended to preserve, is prepared and dissected at leisure, according to the wish of the operator.

When the body has been injected, as above described, the preparation which is made of it easily dries in the open air from the month of May to the month of October; during the winter it is necessary to deposit it in an oven, or in a heated chamber. When the desiccation is slow, or the moisture is excessive, the byssus sometimes develops on its surface, but this may be washed off, and a layer of varnish will prevent new vegetations. This preparation will be certainly superior to any contained in cabinets of anatomy.

In support of this assertion, I will cite an authentic fact, that of a woman whose body was submitted to the examination of the commissioners of the Institute and of the Royal Academy of Medicine, appointed to prove the value of my process.

On the 10th of May, 1834, a woman died in the wards of M. Majendie, at the Hôtel-Dieu; the body was injected the next day with the acetate of alumine; at the termination of this operation, it remained fresh until the 15th of January, 1835, when it dried without experiencing any alteration. The commissioners of the two Academies made experiments upon this body, at different periods. On the 15th of January, 1836, M. Guèneau de Mussy, to assure himself of the state of the cerebral substance, demanded the head to be opened, I profited by this occasion to take off the hairy scalp. The same day, M. Breschet, desiring to know what would result from the exposure of this corpse to the open air, it was suspended beneath the shed of the dissecting rooms (ècole pratique.)

Ten months after, in the month of November of the same year, it had not experienced any alteration. At this period, M. Gaucherant, inspecting overseer of the ècole pratique, wishing to terminate the experiment, the body was sent to the cemetery.

The right arm and forearm, the only parts remaining untouched, after the experiments of MM. the commissioners, were amputated by myself. I preserve this piece, as well as the hairy scalp; I can show them to anatomists to be compared with all the preparations obtained by other processes; none of them, I am convinced will be pronounced comparable to mine. The hairs remain so firmly attached to the scalp, that a strong pull will not detach them; I am quite sure that the injection has penetrated even to the capillary tubes of these organs; my experiments upon cats, dogs, and birds, have demonstrated the penetration of my liquid into the horny organs, hairs, or feathers, which clothe the skin of these animals. These facts will demonstrate all the services which it is capable of rendering naturalists. Finally, no process of tanning could give to the internal surface of the skin an aspect more satisfactory than that which offer other preparations deposited in my cabinet.

2. Preservation in liquids.– The different preservative liquids produce effects very different from the process of desiccation; however, all those employed up to the present day, possess serious inconveniences, as any one may be convinced by reading the very commendable passages which we have extracted from the pamphlet of M. Dumèril. We shall point out some others which he has omitted.

(a.) Nitric Acid, the only one of all the acids, that can be of any use to the anatomists, preserves well, it is true, the preparation of the nerves, hardening their structure, and increasing their nacreous white colour; but it deteriorates all the other structures, it dissolves the gelatine, softens the muscles, and deprives the bones of their calcareous salts; it cannot be other than deleterious to objects of pathological anatomy, and natural history.

(b.) Alcohol, is more serviceable than any other liquor in use, but its high price renders its employment almost impossible for objects of normal anatomy; it hardens and sensibly alters objects of pathological anatomy; and these alterations, however trifling they may be, and unimportant to regular anatomy, are serious for the physician, who cannot have too exact an idea of the progress of disorganization in the living tissues. If alcohol is eminently useful for natural history, its costliness renders it impossible to extend the use of it as far as the interest of science demands.

(c.) Diluted Alcohol, to which is added the deuto-chloride of mercury, is a less expensive liquor; it preserves accurately enough the labours of the naturalist and anatomist, but it is not sufficiently faithful for a pathological anatomy. The same may be said of the hydro-chlorate of soda, the hydro-chlorate of ammonia, the muriate and nitrate of alumine added to alcohol.

(d.) Alum, which we have seen figure in many of the adopted formulæ, is, nevertheless an unprofitable means of preservation. Extensively used in commerce, and employed from time immemorial in dyeing, it has only recently attracted the attention of preparers. This salt, to which the new chemical nomenclature has successively assigned the names of double sulphate, triple sulphate, acid sulphate of alumine and potash; has been experimented upon by myself, and has not answered my expectations. I have investigated the cause of this failure, and think I have found it; in analysing this compound, for every hundred parts I have obtained