полная версия

полная версияHistory of Embalming

The tub was placed in one of the pavilions of the Practical School; and in the same room there were a great number of tables covered with dead bodies for the study of practical anatomy. At the end of two months, the two bodies were withdrawn from the bath, and dissected; no change had taken place in their exterior aspect; the tissues and internal organs were ascertained to be well preserved, and capable of serving for anatomical demonstrations.

Other subjects have been examined by the commission of the Academy of Sciences; they had remained in the same liquor since the 2d of December, 1834, and were still sound at the end of April, 1835.

We thought it our duty to exact of M. Gannal some other experiments; thus, we desired to see injections with this preservative liquor, of the arterial system; we caused another subject to be injected with ordinary fatty matter; and at a later period we had injected into the vessels of the subject which had received the preservative liquor, a matter composed of suet, and of resin, in equal parts, and coloured with cinabar, (sulphate of mercury.) This last injection was successful. The first injection of saline liquid exacted eight quarts of the liquid, which was introduced through the left ventricle of the heart.

The subject examined at the end of two months, was well preserved, did not exhale any fetid odour, and might serve for the common dissection of students.

The commission were desirous to know whether a body would rapidly putrefy, if it were withdrawn from the tub and left upon the table of the amphitheatre, exposed to the air, and to the influence of the putrid emanations from the other bodies. A subject was accordingly withdrawn from the preservative saline liquor, and remained fifteen days exposed to the air; no sensible putrefaction took place during this time; this was during the last fifteen days of April. The muscles of the corpse were seen to dry, and, so to speak, to mummify, whilst the tissues which had not come in contact with the saline liquid, or which had not been uncovered and exposed to the air, remained still in a state which permitted an anatomical analysis.

We ought to remark, that the tissues which are bathed by the liquid lose their natural colours; but the more deeply disposed organs did not experience the same change; there was no emphysema in the cellular tissue, although we thought we remarked that there was less resistance in the fibres of the organs, than in a subject dead for twenty-four or forty-eight hours.

We may remark, that under no circumstances were long and deep scarifications made on the trunk or members, in order to allow the liquid to penetrate the thickness of the tissues. The cranium itself was not opened, nor was there any application of the trephine, in order to permit a more ready entrance of the liquor to the meninges, or to the brain itself. Nevertheless, after more than two months immersion in the liquor, the brain, extracted from the cranium, if it could no longer serve for new researches on its structure, might have been employed for demonstrations.

But, for how much longer time could this preservation be continued? What temperature is it capable of resisting? And what expense does it require? In fine, can the discovery be extensively applied? That is to say, is it possible, by this process, to preserve a great number of subjects during summer, to deliver them later to the students during the season of dissection? And if these subjects, thus preserved, exhale no odour, become in no manner a cause of insalubrity, or of danger to the students, for the anatomists themselves, or for the persons who inhabit the houses adjoining the anatomical amphitheatre, might not the dissections be indefinitely prolonged, in place of permitting them only during the rigors of winter?

In fine, has this saline liquor of M. Gannal preservative properties sufficiently pronounced to be employed during long voyages, and in hot climates, for the purpose of bringing home numerous animals of large size, to serve for the study of comparative anatomy?

The small volume which saline substances occupy, and the sea water, which might serve to make the solution of the salts in any quantity as soon as needed, would be circumstances favourable to the use of this process.

In order to answer all these questions, it would be requisite to multiply the experiments, to extend them during a much longer period, and upon a very great number of subjects.

These experiments, directed in this spirit, would exact expenses which we thought ought not to be imposed upon the author of the process for the preservation of dead bodies, who has already been subjected to a multiplicity of demands, for the reimbursement of which we propose an indemnity from the Academy, without prejudice to the recompense which M. Gannal may have a right to claim, when the experiments shall have received that extension which we wish to be able to give them.

However this may be, we thought, in this provisionary report, that we ought to call the attention of the Academy, and of superior authority, to the process of preservation discovered by M. Gannal, and we manifest the desire that a sum be awarded to him as an indemnification for expenses already accrued, and in order to facilitate the means of continuing his experiments on a large scale.

We shall add that this process of preservation may be very advantageously applied to various cases of legal medicine.

Paris, 16th June, 1835.

Signed,

MM. Gueneau de Mussy,Dizè,Roux,Sanson,Breschet, Reporter.Certified.– The perpetual Secretary of the Academy of Medicine.

Signed,

Pariset.The first report of MM. the members of the commission named by the Academy of Medicine was only provisionary; new facts were discovered to enlighten the conscience of the judges; these facts were presented, and the following report read to the Academy by M. Dizè.

Definitive report of the commission named by the Academy of Medicine, to examine the process of preserving dead bodies, presented by M. Gannal.

Gentlemen, – The Academy had formed a commission composed of MM. Sanson, Guèneau de Mussy, Breschet, Roux, and Dizè, to make known the results of a process presented by M. Gannal, having for its object the preservation of dead bodies destined for dissection.

Our honourable colleague, M. Breschet, presented, in a provisionary report, the experiments which had been made, and the success obtained by M. Gannal.

But the commission having expressed a desire to give more development to trials which, after the important results already obtained, deserved to fix the attention of the Academy, it proposed to him to multiply, to vary the experiments, to extend them a longer time upon a greater number of subjects.

But trials directed in this spirit, exact expenses; the commission did not think it just to impose them upon the author of the process, who had already multiplied expenses; in consequence it proposed to the Academy to demand an indemnity of government for expenses already made, and for the continuance of experiments, without any prejudice to the recompense that M. Gannal would have a right to claim.

The Academy seconded the wishes of the commission; it obtained from the minister of public instruction the sum necessary for covering all expenses made, and for those to be made in the continuance of the experiments.

M Gannal made a series of preliminary experiments, which served him as so many starting points on the road to the discovery of the means of preserving animal matters; these labours subsequently conducted to the research of an antiseptic sufficiently powerful, which unites to the property of preserving bodies, that of not altering the organic tissues, and not too much weakening their natural colours, so important to anatomical demonstrations.

We shall cite the most important experiments, so that you may be able to appreciate the process which is proposed.

In the first place, acids in general modify the consistence of animal matters; they produce disorganization in proportion to their concentration; some diluted acids, for example, nitric acid at five degrees, may serve when it is necessary to study the nervous system, but then the bones lose their saline particles and are reduced to their organic frame; the muscles are discolored and faded, as well as the viscera; the nerves alone remain of a very remarkable mother-of-pearl whiteness.

Arsenious acid preserves bodies very well, but a single subject would require a killogram! Although the medical journals having spoken of a process discovered by Dr. Tranchini, of Naples, the commission judged it expedient to invite M. Gannal to repeat this experiment; a subject was injected with a killogram of arsenious acid and ten quarts of water; this subject examined by your commission, presented all the characters of a good preservation; but, on one hand, this process has been for a long time known, and on the other hand, the employment of it presents so many dangers, that in case of its success your commission would feel themselves obliged to proscribe it; effectually, when twenty subjects were under dissection, there would be twenty killograms of this poisonous substance at the disposition of the public.

Concentrated acetic acid preserves meats, but dries them. This same acid diluted retards putrefaction, but softens the bones, as well as the muscles, which are discolored by its action.

The alkaline salts only preserve meats when they are used dry, or in a very concentrated solution; it is necessary in this case that the salts preserve an affinity for the water of composition, so that it may be said that these salts preserve meats because they dry them; thus, on this principle, salts more soluble in warm, than in cold water, may, injected as a warm concentrated solution, be considered as a means of preservation; this applies particularly to the nitrate of potash.

Creosote, a newly discovered vegetable substance has been recommended as a preservative of flesh; this fact demanded verification: a corpse which had been injected on the 18th of October, with one hundred scruples of creosote and seven quarts of water, was decomposed on the 30th of the same month.32 But, in order to respond to the objection which was made, that the body should have been immersed in a bath saturated with creosote, it is sufficient to say that this bath would have cost forty dollars; besides the necessity of combatting the odour of the creosote, which may prove an obstacle to anatomical labours.

A solution of alum at eight degrees has succeeded better; but the flesh becomes hardened, faded, and friable.

The mixture of alum, (acid sulphate of alumine, and potash,) two parts, the chloride of sodium two parts, and of nitrate of potash one part, dissolved in water, employed as a bath, has afforded the first good results.

The acid phosphate of lime is the first substance which has been employed in injection for subjects; this salt did not oppose the movement of putrefaction.

The kidnies, injected with this salt, and immersed in the milk of lime, became hardened at the surface and putrefied in the interior.

After this first part of the experiments of M. Gannal, it results that the aluminous salts are those alone which succeed well in preserving animal matters, and which may be used advantageously.

Alum, employed alone, preserves well, but for a short time; this salt, slightly soluble in cold water, (fifteen degrees,) will not suffice as an injection for the preservation of a body; it is indispensable to immerse the body in a bath of the same salt.

The mixture of alum, salt, and nitre, as indicated in the provisionary report, has not the same inconvenience; a subject injected with this liquid, at ten or twelve degrees of density, may be preserved for more than a month; but it is indispensable to immerse it, at least from time to time, when it is desirable to prolong its preservation; that is to say, for the entire winter; but at a temperature above fifteen degrees, it is necessary to inject the liquid at a density of twenty-five or thirty degrees, and, in order to obtain it, it requires to be heated at least to forty degrees.

Several bodies injected with this liquid at ten degrees, on the 2d of December, 1834, were well preserved until the end of April; other subjects, injected on the 7th of August, but with the liquid at twenty-five degrees of density, and at ten degrees of the thermometer, were still, on the 10th of December, in good condition, whilst those that were injected with a liquor of inferior density, did not resist a temperature of twenty or twenty-five degrees, although they were immersed in a bath denoting fifteen degrees. The bath of salted liquid has, independently of the inconvenience of expense for the necessary salts and the embarrassment of the tubes, which require frequent renewal, the objection of hardening the skin, considerably.

On these motives new efforts have been made, which have conducted to the following results: to demonstrate that all the salts with a soluble aluminous base, are decomposed; that those which are very soluble offer all the advantages of alum employed in very concentrated solution, and have not the same inconveniences.

For example, a solution of acetate of alumine at twenty degrees, injected the 16th of August, 1835, perfectly preserved a subject abandoned to the table without any other preparation; only, at the end of a month it was remarked that desiccation had commenced; when a part of it was covered with a layer of varnish, which preserved it from further evaporation. At the present day, 25th January, 1836, the varnished part may be dissected as easily as a fresh subject, whilst the other part offers resistance to dissection.

During the first days of September, another subject was injected with acetate of alumine at fifteen degrees; although this was the corpse of a woman who had died from abortion, it was very well preserved.

On the 12th of December, a subject was injected with the chloride of alumine at twenty degrees; this injection did not succeed well, and only three quarts could be introduced. Nevertheless, the body was perfectly well preserved. This want of success in introducing the liquid led to the following observation; that the chloride of aluminium at twenty degrees acts so powerfully on the arterial tubes and obliterates them to such a degree, that it prevents the passage of the liquid; but in order to remedy this inconvenience, it suffices to inject a first quart of the liquid at ten degrees, and the rest at twenty degrees. The chloride of aluminium has all the advantages of the acetate of alumine, and has further that of preserving the muscles of a bright red.

A mixture of acetate of alumine at ten degrees, and the chloride of the same base at twenty degrees, forms a good preservative injection. The use of one of these salts, or the mixture that has just been indicated, offers the advantage of preserving bodies, without its being necessary to subject them to any other preparation.

The density of the solutions of the acetate and chloride of aluminium must be graduated by the state of the atmosphere. When it is required to prolong indefinitely the preservation of the subject, it is essential to employ it at twenty degrees; it is equally necessary, in this case, to cover the subject with a layer of varnish, the sole object of which is to prevent the too prompt desiccation, which would prove an obstacle to dissection.

The first injections were made through the aorta. Subsequently, in order to avoid the laceration of the pectoral parts, the subject was injected through the carotid artery, which always succeeded very well when the liquid was forced both upward and downward.

After the saline injection, at the end of forty-eight hours, coloured grease may be injected; even after two months the same operation may be performed with the same success.

From the series of experiments which we have just exposed, it results:

1. That a solution of alum, of salt, and of nitrate of potash, injected at ten degrees, answers for preserving bodies at a temperature below ten degrees of the thermometer; that, for a more elevated temperature, it is necessary to carry the density to twenty-five or thirty degrees, and immerse the subject in a liquid of ten or twelve degrees.

2. That it is preferable to employ the acetate of alumine, because it preserves better; as the skin experiences no alteration, and as the central organs remain natural, excepting the colour of the muscles which become bleached.

3. That the chloride of aluminium offers the same advantages.

4. That, in order to preserve parts of bodies which have not been injected, it is necessary to immerse them in a mixture of water, and of the acetate or chloride, marking five or six degrees.

But this part of the operation is transferred to the experiments which are to be undertaken on the preservation of objects of pathological anatomy.

Gentlemen, such are the series of experiments made by M. Gannal, since the first provisionary report was presented to you.

The commission has attentively followed the new experiments; the results obtained, demonstrate that by M. Gannal’s process bodies for dissection may be preserved, and the preservation prolonged beyond the term exacted by the most minute investigations.

As we have already stated, the soluble salts with an aluminous base, offer this preservative method without any danger in their use, and they can also be procured at a low price.

Their antiseptic properties are founded on their chemical action, which modifies animal substances either by depriving them of their water of composition, which determines their putrefaction, or in opposing themselves to its immediate action.

It is, then, only an act of justice rendered to M. Gannal, in considering his labour as an important service rendered to science and to humanity, and which may prove of great utility in anatomical explorations, and in legal medicine.

Consequently, your commission has the honour to propose to you the transmission of the present report —

1. To the Minister of Public Instruction, as an object of improvement in anatomical researches, and to reclaim the continuation of his good offices, in affording extension to the experiments for preserving objects of pathological anatomy.

2. To the Minister of Commerce and of Public Works, as an object of public salubrity. On the proposition of a member of the Academy, it was unanimously decided to send the present report to the committee of publication.

Signed, MM. Gueneau de Mussy,Sanson,Breschet,Roux,Dize, Reporter.

Certified.– The perpetual Secretary of the Academy of Medicine.

Signed, Pariset.

Reflections.– The mixture of the acid sulphate of alumine and potash, of the nitrate of potash, and the chloride of sodium, furnished me, at first, with some favourable results. But when new experiments were attempted at a temperature above 10° of centigrade, this liquid, which I only employed as a bath, did not answer my expectations. I then tried to inject bodies with concentrated solution, which were afterwards consigned to a bath of the same nature. The preservation was thus rendered more durable; but still it did not balance the influence of an atmosphere very warm and very humid, prolonged for any length of time.

I observed that after twenty-four hours of immersion of the bodies in the bath, all the alumine was absorbed: this fact, well established, was a gleam of light to me.

Since the preservation is produced by the combination of geline with alumine, and as the alumine furnished by the acid sulphate does not inherit enough of the preservative element, let us have recourse to the salts of alum, richer in alumine, and more soluble in water.

The following are the data on which I rely:

To find a salt of alum capable of effectually preserving bodies, and which, by the moderation of its price, may be extensively employed in amphitheatres. I abandoned my trials with the nitrate of alumine, this being excluded by its high price. The chloride of alumine, with which I had experimented, is liable to equal objections: 1. Because, owing to its excessive affinity for water, it instantaneously dries the internal membrane of the artery, and obliterates the canal, rendering it impossible to finish the injection. 2. Besides, admitting the injection to have been completed by the introduction, in the first place, of a little oil of turpentine, the hydrochloric acid contained in the flesh injures the instruments, and impedes dissection. Further, the chloride of aluminium, like all the soluble chlorides, is a bad agent in dissections, being hygrometric.

The acetate of alumine is an excellent preservative of animal matters, as will be seen by referring to the observation cited at the end of the last chapter; but it is costly, and on this account cannot be employed in amphitheatres.

It was necessary, then, to search for a more economical method; this I have found in the simple sulphate of alumine. This salt, but indifferently known, no one having thought of it before me, is of a simple preparation and moderate price.

A killogram of this salt, costing about twenty cents, dissolved in two quarts of water, is sufficient in winter to preserve a body fresh, by injection, for three months.

In order to preserve a body for a month or six weeks, it is not even necessary to inject the blood-vessels —a glyster of one quart, and the same quantity injected into the œsophagus, suffices for this limited preservation. This process is adopted at Clamart for all the dead bodies destined for dissection. The preservative power of this salt will be easily understood, if its analysis be compared with that of the double sulphate given above.

One hundred parts of simple sulphate of alumine, are composed of alumine 30, of sulphuric acid 70. This salt properly prepared, exempt from iron, commonly contains from thirty-six to forty for 100 of water.

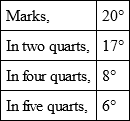

The following is a table of the different densities of this salt, according to the quantity of water in which it is dissolved.

A killogram dissolved in five hundred scruples of water gives a quart of liquid which marks 32° on the areometer of Baumè.

This same quantity in a quart of water

This table is important, as it gives the composition of the different liquids of which we shall see the application.

The liquid of injection, of which we have indicated the preparation and the quantity, is sufficient during winter, and moderate temperatures; but when it passes 20° it ought to be more abundant, or the solution more concentrated.

When it is intended to preserve the body for a longer period, it is necessary to neutralize the sulphuric acid, which is taken up by the addition of acetate of lead. Two hundred and fifty scruples of this salt for one killogram of the dry sulphate produces the desired effect. If the preservation is to be indefinitely prolonged, the use of the acetate of lead will have a tendency at length to blacken the epidermis. Indeed, as it is impossible to cause all the lead to disappear, the small quantity of this salt remaining in the liquid will be then decomposed by the hydro-sulphuric acid disengaged by the corpse, or rather by the sulphur which it contains, and the salt of lead is changed into sulphuret, a black insoluble powder, giving to the body all the exterior aspect of the negro.

I preserved in my cabinet an infant treated after this method; its skin, after the lapse of a year, became black, not of that colour assumed by animal matters in drying, but of the finest negro colour that could be conceived.

I finish with these details; for the facts of prolonged preservation of which we have just spoken are derived from the wants of the anatomists; and, previous to proceeding to other considerations, it is best to exhaust all that we have to make known concerning my processes of preservation applied in amphitheatres to subjects intended to be dissected. The preservation of these subjects, it is known, would be prolonged without any advantage beyond two or three months at all seasons.

I shall therefore terminate all that is relative to this first portion of my labour, by the report of the committee of the members of the Institute. They have admitted the result of my labours to be of great utility, and that it merits the encouragement of the grand Monthyon prize, founded on the discovery of any means calculated to remedy the insalubrity of any art or profession.