полная версия

полная версияHistory of the Royal Regiment of Artillery, Vol. 1

The troops for the sortie paraded at midnight, on the Red Sands, under Brigadier-General Ross. They consisted of the 12th Regiment, and Hardenberg's – two which had fought side by side at Minden – and the Grenadiers and light infantry of the other regiments. There were also, in addition to the Artillery, 100 sailors, 3 Engineers, with 7 officers and 12 non-commissioned officers, overseers, 40 artificers, and 160 men from the line as a working party. A reserve of the 39th and 58th Regiments was also in readiness, if required.

On reaching the works, "The ardour of the assailants was irresistible. The enemy on every side gave way, abandoning in an instant, and with the utmost precipitation, those works which had cost them so much expense, and employed so many months to perfect… The exertions of the workmen, and the Artillery, were wonderful. The batteries were soon in a state for the fire faggots to operate; and the flames spread with astonishing rapidity into every part. The column of fire and smoke which rolled from the works, beautifully illuminated the troops and neighbouring objects, forming altogether a coup d'œil not possible to be described. In an hour, the object of the sortie was fully effected."27

The third epoch, culminating in the grand attack on the 13th September, 1782, is deeply interesting. The fate of Minorca had released a number of Spanish troops, to act against Gibraltar; and large French reinforcements had arrived. On the land side, there were now "Most stupendous and strong batteries and works, mounting two hundred pieces of heavy ordnance, and protected by an army of near 40,000 men, commanded by a victorious and active general, the Duke de Crillon; and animated by the immediate presence of two Princes of the Royal Blood of France." From the sea, the Fort was menaced by forty-seven sail of the line: – "Ten battering-ships, deemed perfect in design, and esteemed invincible, carrying 212 guns; besides innumerable frigates, xebeques, bomb-ketches, cutters, gun and mortar-boats, and smaller craft for disembarking men."[29]

It was during the bombardment immediately preceding the grand attack, that Major Lewis was wounded, and Lieutenant Boag received his second wound, the latter in a singular manner. He was in the act of laying a gun, when a shell fell in the Battery. He immediately threw himself into an embrasure for safety when the shell should explode; but when the shell burst, it fired the gun under whose muzzle he lay. Besides other injury, the report deprived him of hearing, and it was very long ere he recovered. Another officer of the Artillery, Major Martin, had a narrow escape at the same time, a 26-pounder shot carrying away the cock of his hat, near the crown.

The 26-pounder was a very common gun, both in the Rock and in the enemy's land-batteries; but as it was not used on board their ships, and to prevent them returning the shot of the garrison against themselves, all the 26-pounders were moved to the seaward batteries, and fired against the ships, guns of other calibres being employed against the land forces.

The battering ships, with their supposed impregnable shields, were the mainstay of the enemy's hopes; but the use of red-hot shot by the garrison made them after a time perfectly useless.

When the cannonade was at its highest pitch, on the day of the grand attack, "the showers of shot and shell which were directed from the enemy's land-batteries, the battering-ships, and, on the other hand, from the various works of the garrison, exhibited a scene of which, perhaps, neither the pen nor pencil can furnish a competent idea. It is sufficient to say that four hundred pieces of the heaviest Artillery were playing at the same moment: an instance which has scarcely occurred in any siege since the invention of those wonderful engines of destruction."28

At first the battering-ships seemed to deserve their reputation. "Our heaviest shells often rebounded from their tops, whilst the 32-pound shot seemed incapable of making any visible impression upon their hulls… Even the Artillery themselves at this period had their doubts of the effect of the red-hot shot… Though so vexatiously annoyed from the Isthmus, our Artillery totally disregarded their opponents in that quarter, directing their sole attention to the battering-ships, the furious and spirited opposition of which served to excite our people to more animated exertions. A fire, more tremendous, if possible, than ever was therefore directed from the garrison. Incessant showers of hot balls, carcasses, and shells of every species flew from all quarters; and as the masts of several of the ships were shot away, and the rigging of all in great confusion, our hopes of a speedy and favourable decision began to revive."29

Towards evening, signs of great distress and confusion were visible on board the ships, and the Admiral's ship was seen to be on fire. But not until next morning did the garrison realize how great was their advantage. In the meantime the fire was continued, though less rapidly; and "as the Artillery, from such a hard-fought day, exposed to the intense heat of a warm sun, in addition to the harassing duties of the preceding night, were much fatigued; and as it was impossible to foresee what new objects might demand their service the following day; the Governor about six in the evening, when the enemy's fire abated, permitted the majority of the officers and men to be relieved by a piquet of a hundred men from the Marine Brigade; and officers and non-commissioned officers of the Artillery were stationed on the different batteries, to direct the sailors in the mode of firing the hot shot."[31]

During the night, several of the battering-ships took fire, and the scenes on board were terrible. Next day "three more blew up, and three were burnt to the water's edge;" and of the only two remaining, one "unexpectedly burst out into flames, and in a short time blew up, with a terrible report," and the other was burnt in the afternoon by an officer of the English navy.

"The exertions and activity of the brave Artillery," says Drinkwater, "in this well-fought contest, deserve the highest commendations… The ordnance and carriages in the Fort were much damaged; but by the activity of the Artillery, the whole sea-line before night was in serviceable order… During this action the enemy had more than three hundred pieces of heavy ordnance in play; whilst the garrison had only eighty cannon, seven mortars, and nine howitzers in opposition. Upwards of 8300|rounds, more than half of which were hot-shot, and 716 barrels of powder, were expended by our Artillery… The distance of the battering-ships from the garrison was exactly such as our Artillery could have wished. It required so small an elevation that almost every shot took effect."

On the 13th, the day of the attack, Captain Reeves and five men of the Royal Artillery were killed: Captains Groves and Seward, and Lieutenant Godfrey, with twenty-one men, were wounded.

It was, indeed, as Carlyle says, a "Doom's-blast of a No," which the Artillery of Gibraltar answered to the summons of this grand attack.

After the failure of the attack, the enemy did not discontinue their old bombardment, nor did the gunboats fail to make their nightly appearance, and molest the inhabitants longing for rest. The Governor accordingly directed the Artillery to resume the retaliation from the Old Mole Head with the highly-elevated guns against the enemy's camp. The command of the Royal Artillery now lay with Colonel Williams, an officer who joined the service as a cadet-gunner in 1744, and died at Woolwich in 1790.

The work of the Artillery in the interval between the grand attack and the declaration of peace was incessant, day and night.

On the 2nd February, 1783, exchange of shots ceased; and letters were sent by the Spanish to the Governor announcing that the preliminaries of peace were signed at Paris. From this date, courtesies were constantly exchanged. It was on the occasion of a friendly visit of the Duke de Crillon to the Fort, that on the officers of Artillery being presented to him he said, "Gentlemen! I would rather see you here as friends, than on your batteries as enemies, where you never spared me."

The siege had lasted in all three years, seven months, and twelve days; and during this time the troops had well earned the expressions used with regard to them by General Eliott, when he paraded them to receive the thanks of the Houses of Parliament, – "Your cheerful submission to the greatest hardships, your matchless spirit and exertions, and on all occasions your heroic contempt of every danger."

To the Artillery, for their share in this matchless defence, there came also the commendation of their own chief, the Master-General of the Ordnance, then the Duke of Richmond. The old records of the Regiment seem to sparkle and shine as one comes on such a sentence as this: – "His Majesty has seen with great satisfaction such effectual proofs of the bravery, zeal, and skill by which you and the Royal Regiment of Artillery under your command at Gibraltar have so eminently distinguished yourselves during the siege; and particularly in setting fire to, and destroying all the floating batteries of the combined forces of France and Spain on the 13th September last."

There was so much in the Peace of 1783 that was painful to England, not so much in a military as in a political point of view, but undoubtedly in the former also, that one hesitates to leave this bright spot in the history of the time, and to turn back to that weary seven years' catalogue in America, of blunders, dissensions, and loss. It was one and the same Peace which celebrated the salvation of Gibraltar, and the loss of our American Colonies. A strong arm saved the one: a foolish statesmanship lost the other. But be statesmen wise or foolish, armies have to march where they order; and the history of a foolish war has to be written as well as that of a wise one.

It was October, 1783, ere the companies of the Royal Artillery which had been present at the Great Siege returned to Woolwich on relief. The next active service they saw was in Egypt in 1801, when three of them, Nos. 1, 2, and 4 Companies of the Second Battalion, were present with Abercromby's force at the Battle of Alexandria, and during the subsequent operations.

To serve in one of these companies is to serve in one whose antecedents as Garrison Artillery are unsurpassed. Their story is one which should be handed down among the officers and men belonging to them: for they have a reputation to maintain, which no altered nomenclature can justify them in allowing to become tarnished.

There is no fear of courage being wanting; but the standard from which there should be no falling away is that of conduct and proficiency, worthy of the old proficiency maintained under such harsh circumstances, and of the old conduct which shone so brightly in the "cheerful submission to the greatest hardships."

CHAPTER XXVI.

PORT MAHON

The military importance of the capture of Minorca from the English in 1782 was not, perhaps, such as to warrant a separate chapter for its consideration. But the defence of St. Philip's Castle by the English against the combined forces of France and Spain was so exceptionally gallant, their sufferings so great, and the zeal and courage of the Artillery, especially, so conspicuous, that something more than a passing mention is necessary in a work of this nature.

The siege lasted from the 19th August, 1781, to the 5th February, 1782. General Murray was Governor, and Sir William Draper, Lieutenant-Governor. The strength of the garrison at the commencement of the siege was 2295 of all ranks; at the end of the siege, this number had been reduced to 1227, but so many of these were in hospital, that the whole number able to march out at the capitulation did not exceed – to use the Governor's own words – "600 old decrepit soldiers, 200 seamen, 170 of the Royal Artillery, 2 °Corsicans, 25 Greeks, Moors, &c."

In a postscript to the official report of the capitulation the Governor says: – "It would be unjust and ungrateful were I not to declare that from the beginning to the last hour of the siege, the officers and men of the Royal Regiment of Artillery distinguished themselves. I believe the world cannot produce more expert gunners and bombardiers than those who served in this siege." This alone would make imperative some notice of this siege in a narrative of the services of the Corps.

In the Castle of St. Philip's, there were at the commencement of the siege 234 guns and mortars. At the end, no less than 78 of these had been rendered unserviceable by the enemy's fire. The batteries were almost demolished, and the buildings a heap of ruins.

The following officers of the Royal Artillery were present:

Major Walton.

Captains: Fead, Lambert, Schalch, Parry, and Dixon.

First Lieutenants: Irwin, Woodward, Lemoine, Neville, and Bradbridge.

Second Lieutenants: Hope, Wulff, and Hamilton.

In addition to the Artillery the garrison was composed of two Regiments of British, and two of Hanoverian troops.

The commandant of the enemy's forces was the Duke de Crillon, the same officer who after the capitulation of St. Philip's proceeded to command at the Siege of Gibraltar. He drew upon himself a well-merited rebuke from General Murray, whom he had endeavoured to bribe, with a view to the immediate surrender of the Castle; a rebuke which he felt, and answered with great respect and admiration.

There is in the Royal Artillery Record Office a journal kept during the siege by Captain F. M. Dixon, R.A., from which the following details are taken, many of which would lose their force if given except in the writer's own words. The siege commenced on the 20th August, when there was nothing but confusion and disorder within St. Philip's, to which the troops had retired; but the enemy did not commence firing on the Castle until the 15th September. The English had not been so quiet; they commenced firing at a great range on the 27th August, and with great success. At the request of the Duke de Crillon, all the English families had been sent out, in humane anticipation of the intended bombardment. Desertion from the enemy was frequent at first; and as the siege progressed it was occasional from the British troops. When a deserter was captured, he received no mercy.

The most deadly enemy of the garrison was scurvy. Hence an order on the 7th November, 1781, for an officer and six men per company to be told off daily to gather pot-herbs on the glacis. Anything of a vegetable nature brought a fabulous price; tea was sold at thirty shillings a pound; the number of sick increased every day, the men concealing their illness to the last rather than go to hospital, and very frequently dying on duty from sheer exhaustion: – "Our people," says the diary, "do more than can be expected, considering their strength; the scurvy is inveterate… 108 men fell sick in two days with the scurvy… I am sorry our men are so very sickly; our people fall down surprisingly, we have not a relief… The Hanoverians die very fast: there is no fighting against God… Our troops increase vastly in their sickness;" and so on. Among those who fell a victim during the siege was Captain Lambert, of the Artillery.

So heavy were the duties that even the General's orderly sergeants were given up to diminish the burden; and when the capitulation was resolved upon, it was found that while the necessary guards required 415 men, there were only 660 able to carry arms, leaving, as the Governor said, no men for piquet, and a deficiency of 170 men to relieve the guard. Against this small force, entrenched in what was now a mere heap of rubbish, there was an enemy, whose lowest number was estimated at 15,000, and was more likely 20,000.

Some of the enemy's batteries were armed with 13-inch mortars. When the British ammunition ran short, the shells of the enemy which had not burst were returned to them, and in default of these, stone projectiles were used with much effect.

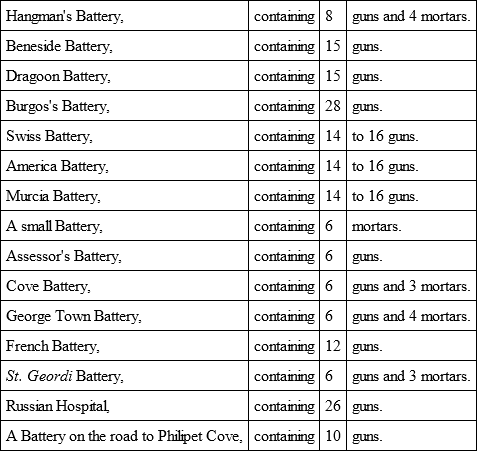

On the 12th December, 1781, the following batteries had been opened against the Castle: —

But the above list does not exhaust the number which ultimately directed their fire on the Castle. New batteries were prepared without intermission, hemming in with a deadly circle the devoted garrison. Some extracts from Captain Dixon's diary will give some idea of the fire to which the place was subjected: —

January 6th, 1782. "A little before seven o'clock this morning they gave three cheers and fired a feu de joie; then all their batteries fired upon us with great fury, which was equally returned by our brave Artillery. Our General declared he had never seen guns and mortars better served than ours were."

January 7th, 1782. "Such a terrible fire, night and day, from both sides, never has been seen at any siege. We knew of 86 brass guns and 40 mortars against us… Our batteries are greatly demolished; it is with great difficulty that we can stand to our guns."

January 9. "All last night and this day they never ceased firing, and we as well returned it. You would have thought the elements were in a blaze. It has been observed they fire about 750 shot and shell every hour. Who in the name of God is able to stand it? We hear they have 200 guns in their park."

January 10. "The enemy had 36 shells in flight at the same time. God has been with us in preserving our people: they are in high spirits, and behave as Englishmen. Considering our small garrison, they do wonders. Our Generals constantly visit all the works… A great number of shells fell within the limits of the Castle… A shell fell in the General's quarters, wounded Captain Fead of the Artillery, and two other officers."

January 11. "The enemy keep up, if possible, a fiercer fire than yesterday. A man might safely swear, for six days past, the firing was so quick that it was like a proof at Woolwich of 200 cannon. About a quarter past six, the enemy began to fire shells, I may say innumerable."

January 19. "Never was Artillery better served, I may say in favour of our own corps."

January 20. "This night shells meet shells in the air. We have a great many sick and wounded, and those that have died of their wounds… Our sentries have hardly time to call out, 'A shell!' and 'Down!' before others are at their heels."

January 24. "The Artillery have had hard duty and are greatly fatigued. The scurvy rages among our men."

The casualties among the small garrison, between the 6th and 25th of January, 1782, included 24 killed, 34 died, 71 wounded, and 4 deserted.

January 28, 1782. "They fire shot and shell every minute. The poor Castle is in a tattered and rotten condition, as indeed are all the works in general… The Castle and every battery round it are so filled by the excavations made by the enemy's shells, that he must be a nimble young man who can go from one battery to another without danger. The Castle, their grand mark, as well as the rest of the works, are in a most shocking plight."

On the 4th February, a new and powerful battery of the enemy's, on a very commanding situation, being ready to open fire, a white flag was hoisted, the drums beat a parley, and an officer was sent out with the proposed terms of capitulation; which were ultimately amended and agreed to. By the second Article of the Treaty, "in consideration of the constancy and valour with which General Murray and his garrison have behaved by their brave defence, they shall be permitted to march out with shouldered arms, drums beating, matches lighted, and colours flying, until they get towards the centre of the Spanish troops." This was done at noon on the following day, between two lines of the Spanish and French troops. So pitiable and deplorable was the appearance of the handful of men who marched out that the conquerors are said to have shed tears as they looked at them. In the official report of General Murray, he alludes to this, saying that the Duke de Crillon averred it to be true. When the men laid down their arms, they declared that they surrendered them to God alone, "having the consolation that the victors could not plume themselves upon taking a hospital."

Captain Schalch was the senior officer of Artillery left to march out at the head of the dwindled and crippled remnant of the three companies. Of them, and their comrades of the other arms, the Governor said in a final General Order, dated at Mahon, 28th February, 1782, that he had not words to express his admiration of their brave behaviour; and that while he lived he should be proud of calling himself the father of such distinguished officers and soldiers as he had had the honour to command.

So ended the Train of Artillery for Port Mahon, which the reader will remember was one of those quoted in 1716 as a reason for some permanent force of Artillery at home. Since 1709, with a short interval in the time of the Seven Years' War, a train had remained in Minorca; but now, overpowered by numbers, the force of which it was a part had to evacuate the island. It was a stirring time for the Foreign establishments, as they were called in pre-regimental days: that in Gibraltar was earning for itself an immortal name; those in America were within the clouds of smoke and war which covered the whole continent; and this one had just been compelled to die hard. Of the four, which were used as arguments for the creation of the Royal Regiment of Artillery, only one remains at this day – that at Gibraltar. Those at Annapolis and Placentia have vanished before the breath of economy, and the dawn of a new colonial system; and in this brief chapter may be learnt the end of the other, the Train of Artillery for service at Port Mahon.

N.B.– It is worthy of mention, that during this siege, three non-commissioned officers, Sergeants-Major J. Swaine, J. Shand, and J. Rostrow, were commissioned as Second Lieutenants in the Regiment, by the Governor, for their gallantry. They were afterwards posted to the Invalid Battalion.

CHAPTER XXVII.

The American War of Independence

There are few campaigns in English history which have been more systematically misunderstood, and more deliberately ignored, than the American War between 1775 and 1783. The disadvantages under which the British troops laboured were many and great; they were not merely local, as in most English wars, but were magnified and intensified by the unpopularity of the campaign at home, by the positive hostility of a large party, including some of the most eloquent politicians, and by the inflated statements of the Government, which made the tale of disaster – when it came to be known – more irritating and intolerable.

Soldiers will fight for a nation which is in earnest: British soldiers will even fight when they are merely the police to execute the wishes of a Government, instead of a people. But in the one case they are fired with enthusiasm, – in the other, their prompter is the coldest duty.

The American War was at once unpopular and unsuccessful. When it was over, the nation seemed inspired by a longing to forget it; it was associated in their minds with everything that was unpleasant; and the labour of searching for the points in it which were worthy of being treasured was not appreciated. English historians have always been reluctant to pen the pages of their country's disasters; and their silence is at once characteristic of, and thoroughly understood by, the English people. There has, however, been a species of self-denying ordinance laid down by English writers, and spouted ad nauseam by English speakers, in which the whole blame of this war is accepted almost greedily and its losses painted in heightened colours as the legitimate consequences of national error. England was to blame – taxation without representation undoubtedly is unjust; but were American motives at the outset pure? It may readily be granted that after the first shedding of blood the resistance of the colonists was prompted by a keen sense of injury such as might well animate a free and high-spirited people; but, before the sword was drawn, the motives of the Boston recusants no more deserve to be called worthy, than the policy of England deserves to be called statesmanship.

England, with the name, had also the responsibilities of a mighty and extended empire. Her colonies had the name and the advantages, without the responsibilities. The parent was sorely pressed and heavily taxed, to protect the children; the children were becoming so strong and rich that they might well be expected to do something for themselves. The question was "How?" It is only just to say that when the answer to the question involved the defence of their own soil by their own right hand, no more eager assistants to the Empire could be found than our American colonists. But when they were asked to look beyond their own shores, to contribute their share to the maintenance of the Empire elsewhere – perhaps no bad way of ensuring increased security for themselves – the answer was "No!" They would shed their blood in defence of their own plot of ground; but they would not open their purses to assist the general welfare of the Empire.