полная версия

полная версияHistory of the Royal Regiment of Artillery, Vol. 1

In days long after John Turner's career was finished, the spectacle has been witnessed of an invaded country straining every nerve, and practising every self-denial, to procure the withdrawal from its occupied districts of the enemy's troops. It is questionable, however, whether its eagerness was equal to that which must have been felt on all sides when that memorable event occurred which it has been attempted to describe, – the invasion of Morocco by a bombardier.

In the year 1770, the Regiment suffered from two evils: one, the chronic slowness of promotion which has always afflicted it; the other, an inability to carry out the foreign reliefs with so small a number of companies at home. To meet these evils a remedy was devised, which shall be treated in the next chapter – the formation of another Battalion.

CHAPTER XXIII.

The Fourth Battalion. – The History and Present Designation of the Companies

This Battalion was formed on the 1st January, 1771, by drafting six companies from the Battalions already in existence, which were thus reduced from ten to eight companies, and by the formation, in addition, of two new companies. At the same date, eight companies of invalids were formed from the men on out-pension, two of which were attached to each Battalion, but were not borne upon the effective strength. These eight companies were consolidated in 1779 in one invalid battalion, with a regular staff, and effective companies were raised for the other battalions, in their stead.

On its first formation, the companies of the 4th Battalion were very weak, consisting each of 1 Captain, 1 Captain-Lieutenant, 2 First Lieutenants, 2 Second Lieutenants, 2 Sergeants, 2 Corporals, 4 bombardiers, 8 gunners, 52 matrosses, and 2 drummers. The staff of the Battalion consisted of a Colonel-Commandant, a Lieutenant-Colonel, a Major, an Adjutant, a Quartermaster, and a Chaplain. Colonel Ord, the first Colonel-Commandant, had greatly distinguished himself in North America in 1759 and 1760; and it was a happy coincidence that he should receive the command of a battalion whose services in that country were destined to be so brilliant. These services will receive more appropriate mention in the chapters connected with the American War of Independence, and with the gallant officer who commanded it during that war, General James Pattison.

But two of the companies received special marks of distinction which deserve to be mentioned. One, No. 1 Company, now No. 4 Battery, 7th Brigade, was singled out after the battle of Vaux, in 1794, for its gallant conduct during the day, and the whole Army was formed up to see it march past the Duke on the field of battle. Another company, No. 10, received a special mark of distinction for its gallantry during the second American War, and more especially at the capture of Fort Niagara. By General Order of 7th October, 1816, it was permitted to wear on its appointments "in addition to any badges or devices which may have been hitherto granted to the Royal Regiment of Artillery" the word "Niagara." This company subsequently fell a victim to change and reduction. It was reduced in January, 1819, after a service of forty years, having been one of the two companies formed in 1779 to replace the invalid companies of the Battalion. It was reformed at Woolwich on the 16th August, 1848; and on the 3rd November in that year it became No. 6 Company of the 12th Battalion. In 1859, when the Brigade system was introduced, it became No. 9 Battery of the 6th Brigade; on the 1st April, 1865, it was transferred to the 12th Brigade as No. 8 Battery; and on the 1st February, 1871, by reduction, it ceased to exist as such. It is a matter of regret that the pruning-knife should be applied to the companies which have a distinctive history.

The 4th Battalion afforded a precedent – although not a happy one – for the Brigade system as applied to the Royal Artillery. It was the only battalion which ever went on service with its head-quarter staff. Experience soon proved that it would have been better to leave that appendage – as was customary – at Woolwich. The Battalion letter-books teem with complaints as to clothing, recruiting, and pay, which might have been obviated by having at home the usual battalion officials, whose duties were connected with these details. With the companies detached over the American continent, and the head-quarters virtually imprisoned in New York, the confusion was endless, and the natural results excite a smile as the student reads of them. For the officials at the Board of Ordnance exercised the same paternal interference over the distant staff, as if they had been in Woolwich. The time occupied by correspondence across the Atlantic, rendered necessary by the stupidity and the curiosity of the Ordnance officials, told heavily against the comfort of the companies, and the peace of mind of their Captains. The circumlocution between London and New York, New York and all the stations on the continent where detachments of the Battalion were stationed, and back again to the Tower, was at once ludicrous and irritating. And the trouble caused by the absence from England of those who would have interested themselves in procuring suitable and creditable recruits cannot be realized save by those who have waded through the letter-books of the period. The companies were fettered to a beleaguered head-quarters, which in its turn was tied and bound to a distant department, nor was allowed the slightest independence of action. The result may easily be imagined. Questions which could have been decided in a few minutes, if those interested could have met, grew every day more complicated and unwieldy by the correspondence at long and uncertain intervals in which the Board of Ordnance revelled.

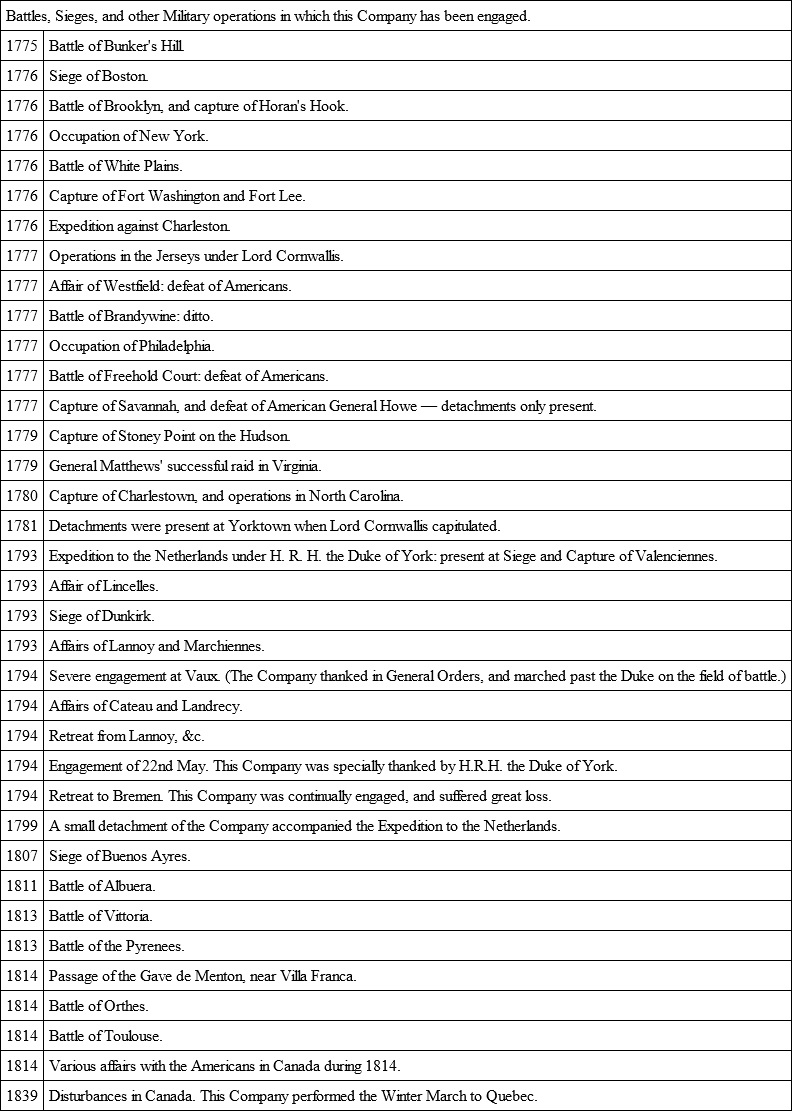

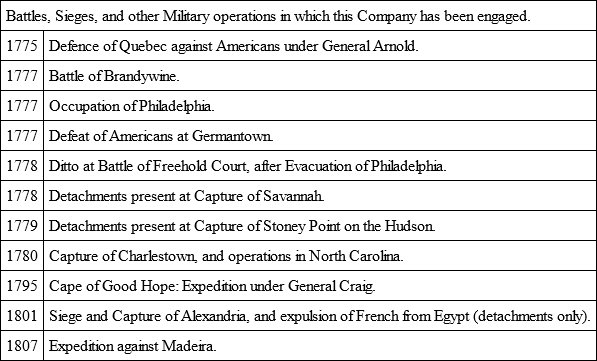

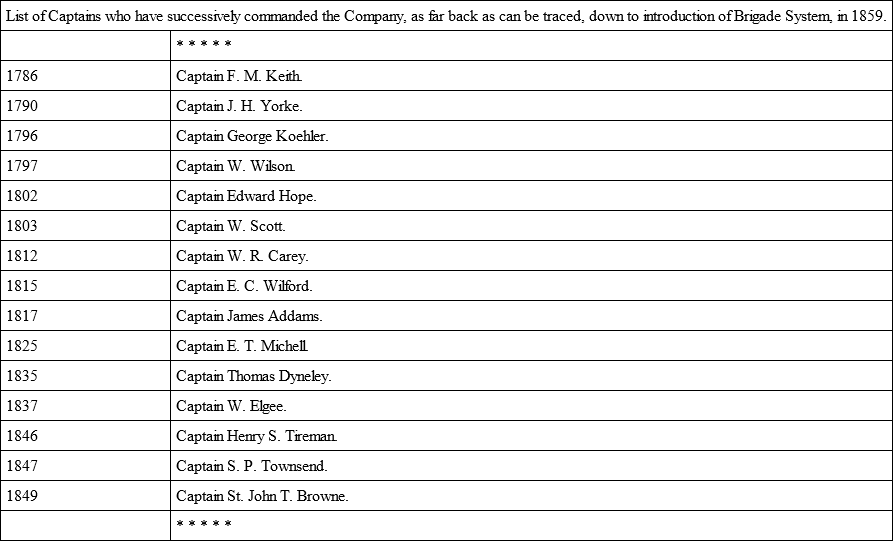

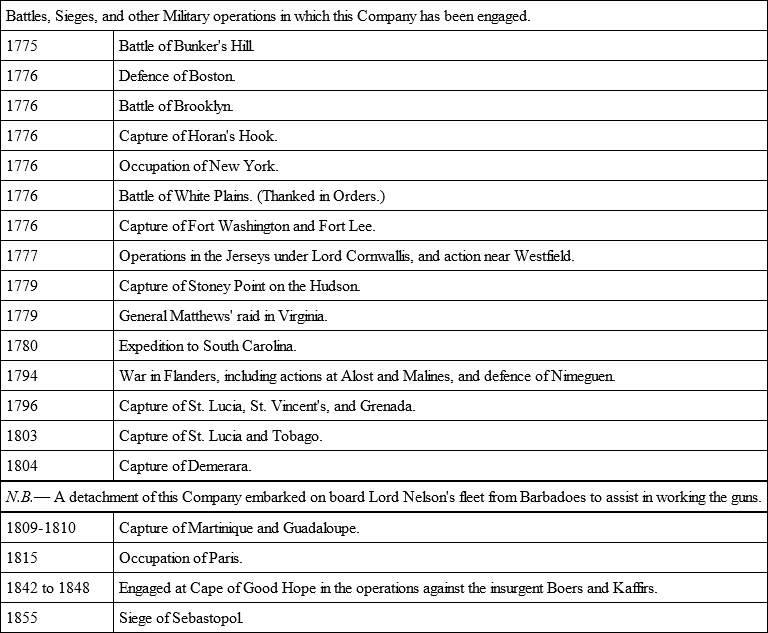

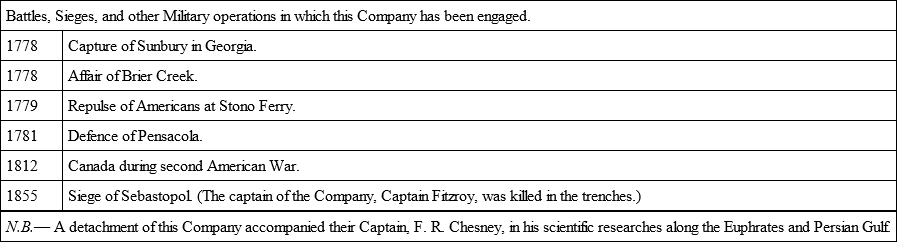

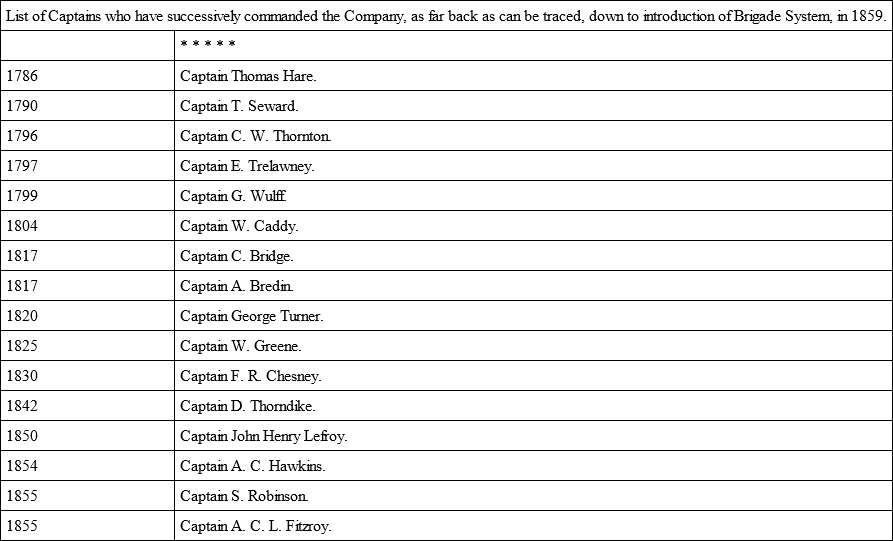

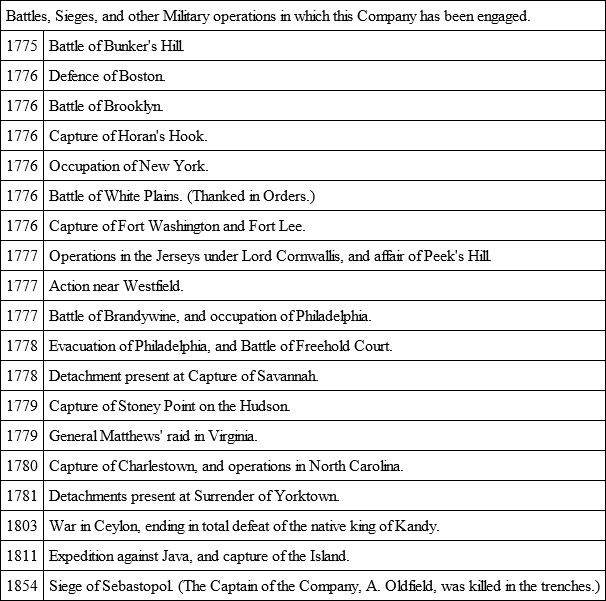

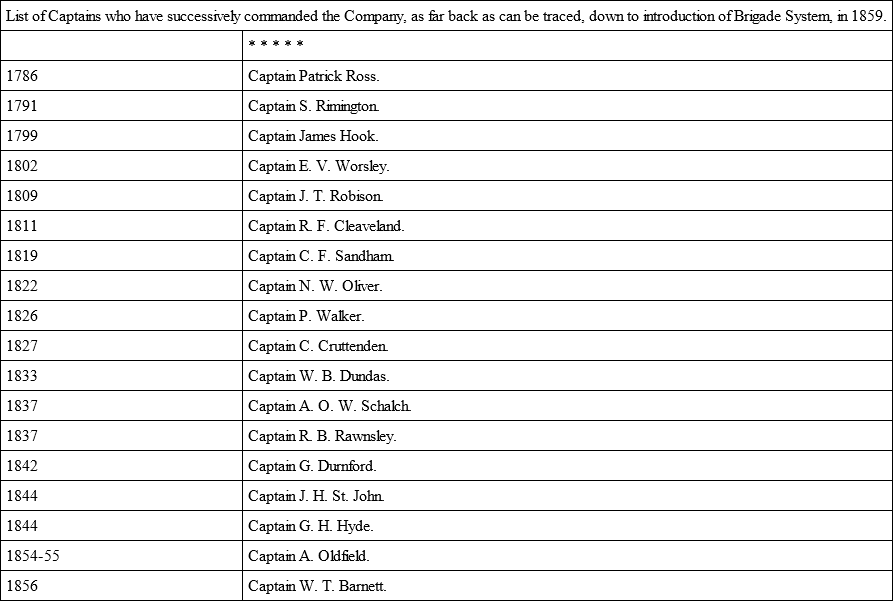

The services of the companies will now be given, in the same manner as those of the other battalions. There are few lists more noble than that of the military operations in which No. 1 Company was engaged. The battery – No. 4 of the 7th Brigade – whose history this is, may well be proud of such noble antecedents. The revival of these may prove a means of awakening a pride in its ranks which will be the strongest aid to discipline, the most powerful incentive to progress.

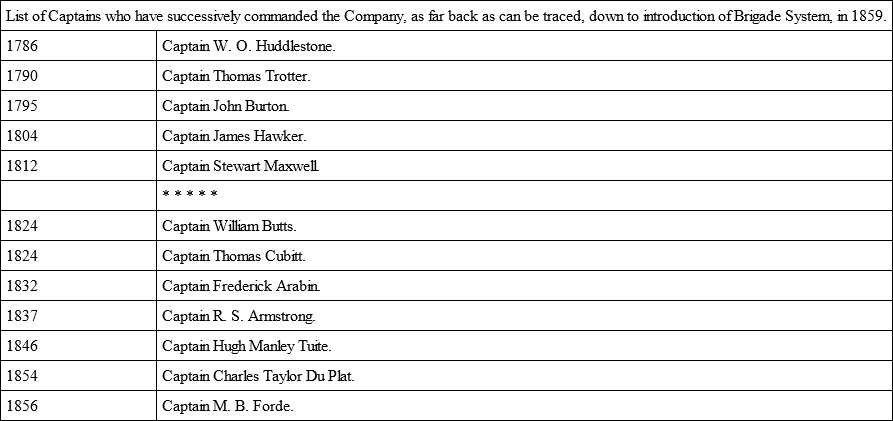

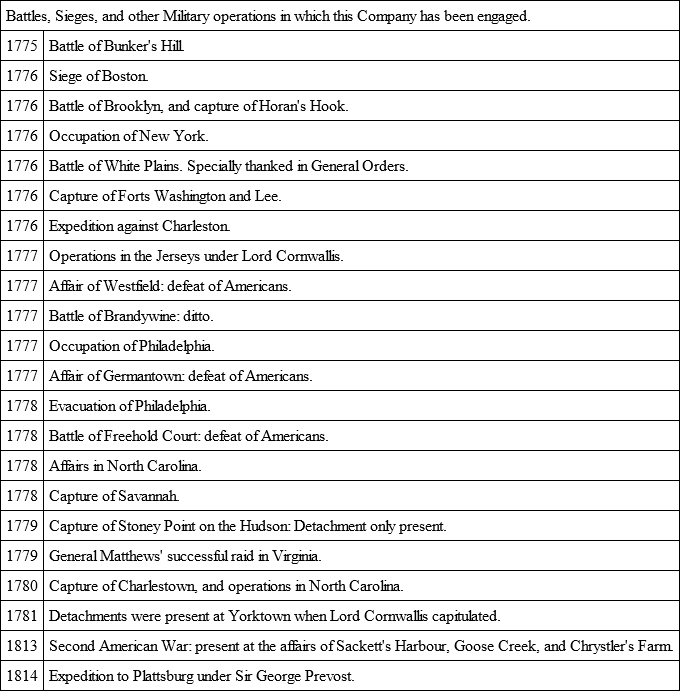

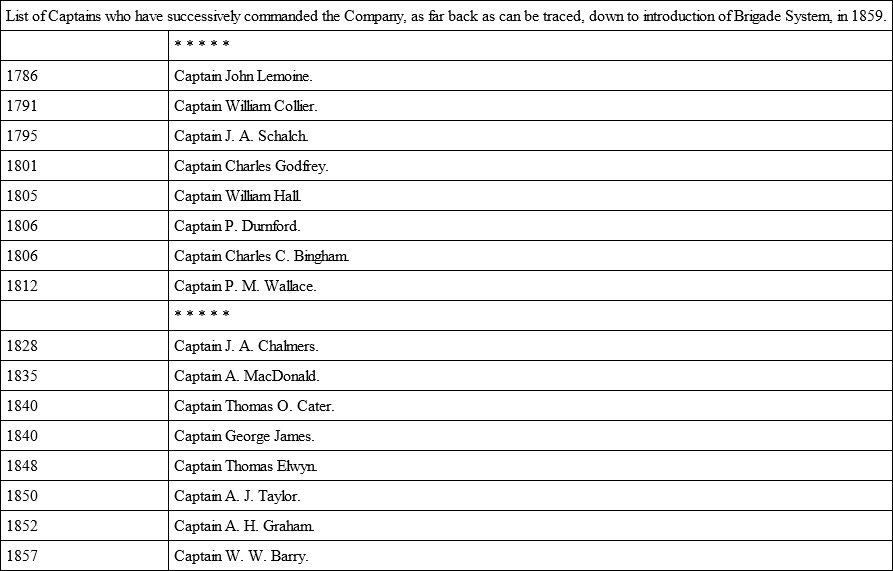

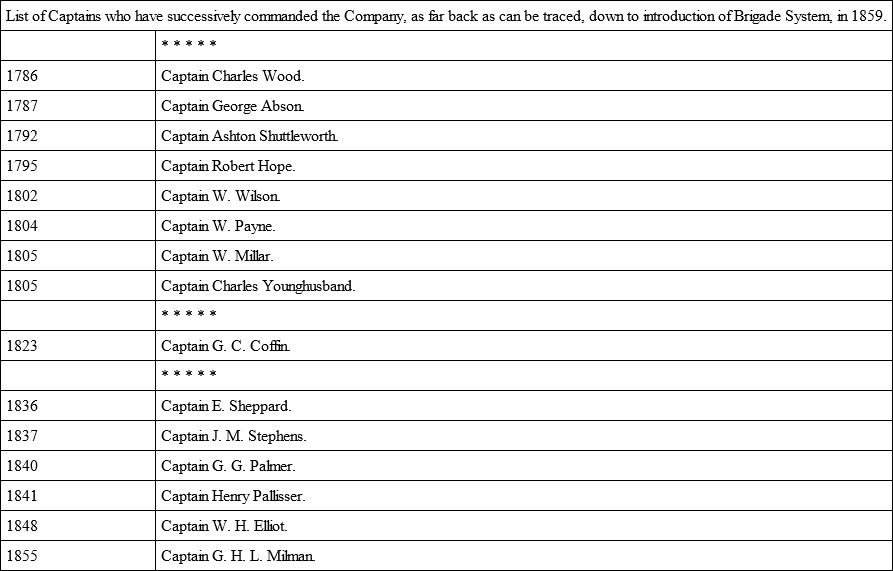

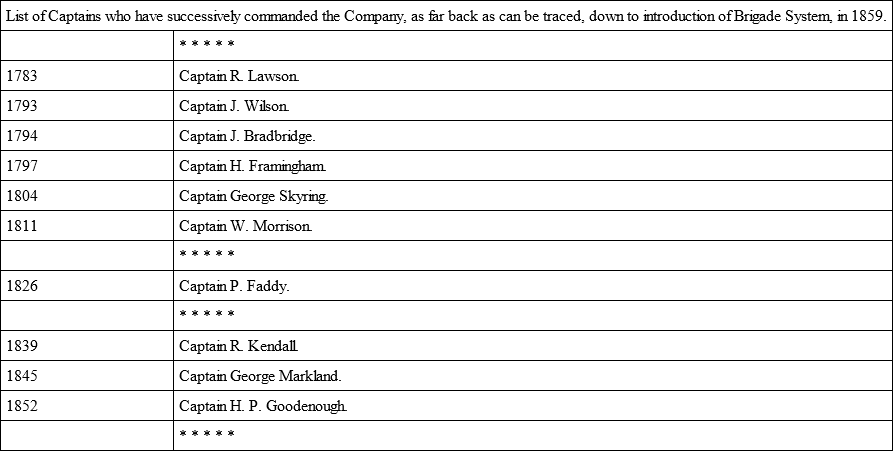

The succession of Captains of the various companies, as far as the somewhat mutilated records on this point will admit, will also be given, down to the time when the nomenclature of the companies was changed, since which date, so recent, no difficulty will be found in continuing the lists.

No. 1 COMPANY, 4th BATTALION,

Now "4" BATTERY, 7th BRIGADE.

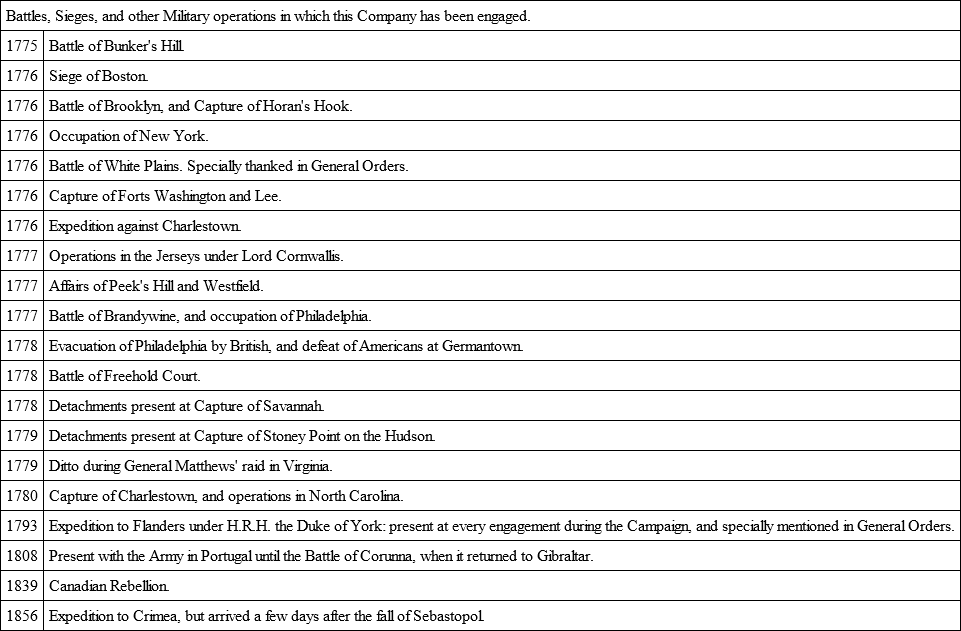

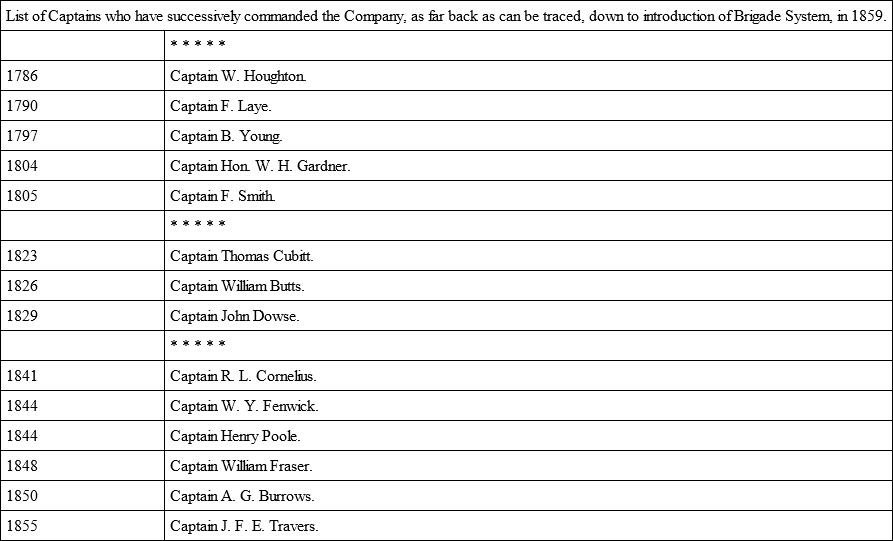

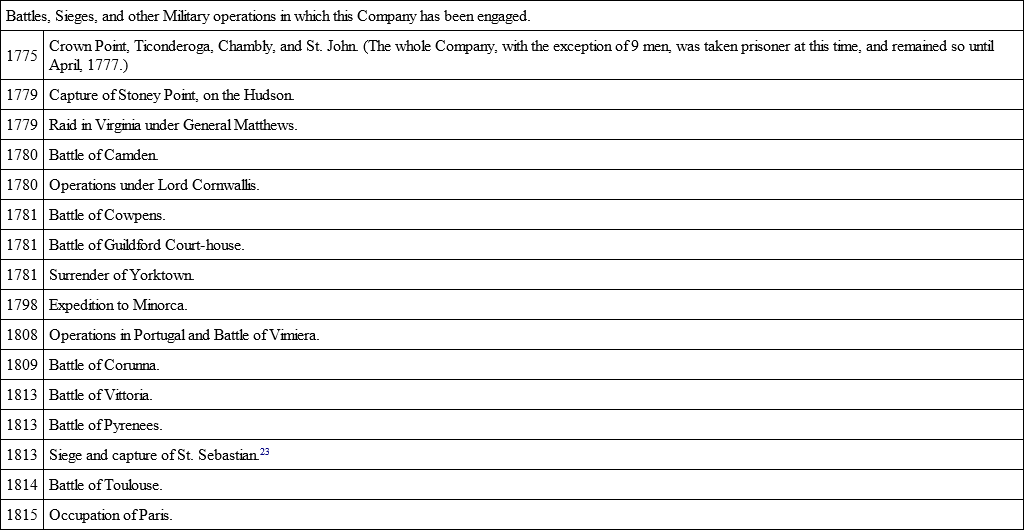

No. 2 COMPANY, 4th BATTALION,

Now "6" BATTERY, 3rd BRIGADE.

No. 3 COMPANY, 4th BATTALION,

Now "8" BATTERY, 2nd BRIGADE.

No. 4 COMPANY, 4th BATTALION,

Afterwards "8" BATTERY, 1st BRIGADE.

Reduced 1st April, 1869.

No. 5 COMPANY, 4th BATTALION,

Now "B" BATTERY, 9th BRIGADE.

No. 6 COMPANY, 4th BATTALION,

Now "1" BATTERY, 6th BRIGADE.

Примечание 123

No. 7 COMPANY, 4th BATTALION,

Now "6" BATTERY, 10th BRIGADE.

No. 8 COMPANY, 4th BATTALION,

Now "E" BATTERY, 1st BRIGADE.

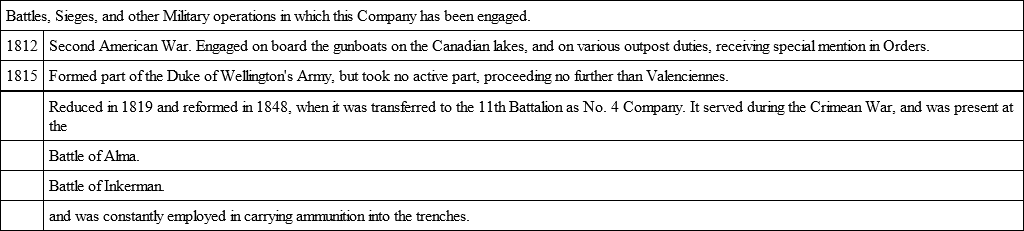

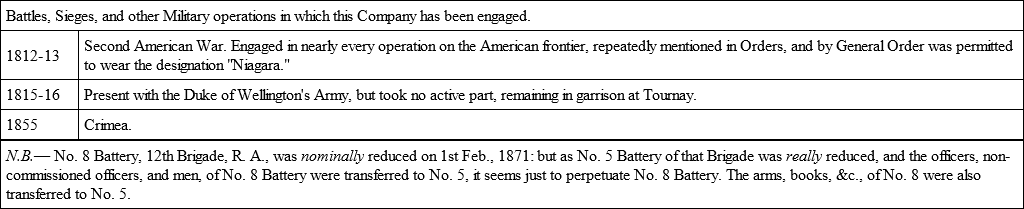

No. 9 COMPANY, 4th BATTALION,

(Afterwards 4th Company, 11th Battalion),

Now "H" BATTERY, 4th BRIGADE.

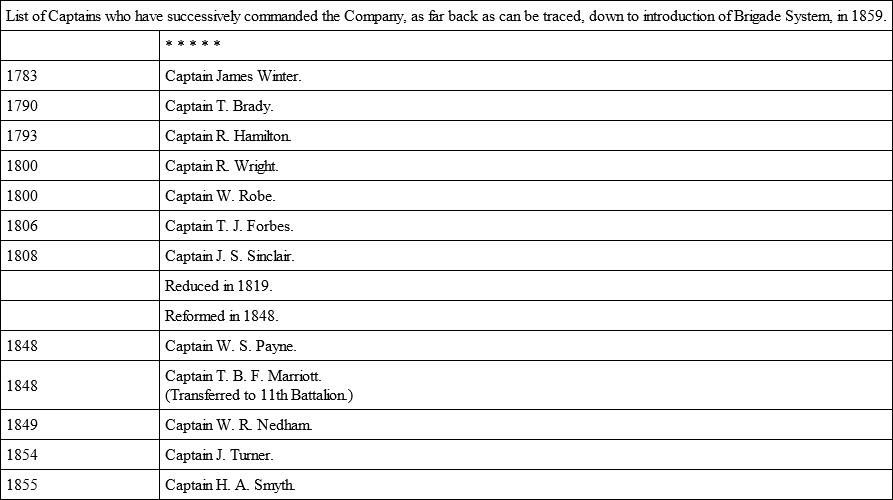

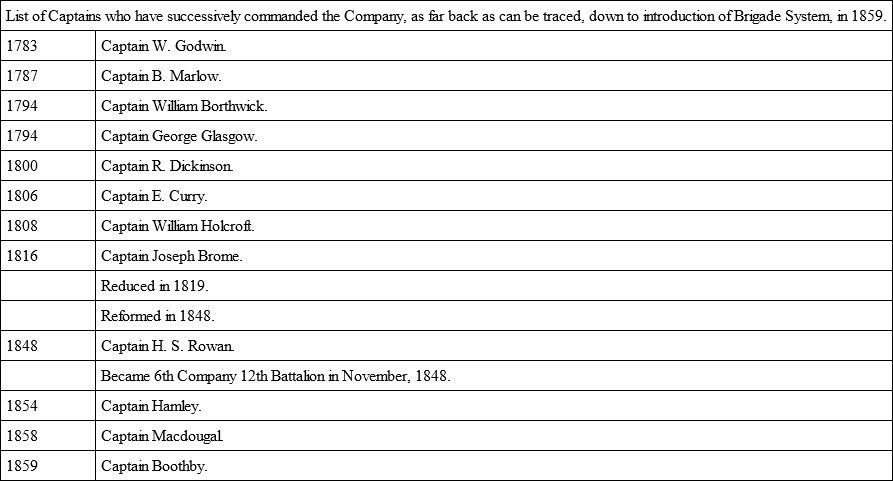

No. 1 °COMPANY, 4th BATTALION,

Afterwards "8" BATTERY, 12th BRIGADE,

Now "5" BATTERY, 12th BRIGADE.

CHAPTER XXIV.

The Journal of a Few Years

For a few years after the formation of the Fourth Battalion, the History of the Regiment contains little that possesses more than domestic interest. It was the stillness which precedes a storm.

In 1775, the Titanic contest commenced, in which England found herself pitted against France, Spain, and her own children.

From that year, until 1783, the student of her military history finds his labour incessant. America and Europe alike claim his attention; the War of Independence, and the Sieges of Gibraltar and Port Mahon, furnish a wealth of material for his examination.

But before entering on these, the ground must be cleared and the regimental gossip between 1771 and 1775 must be chronicled.

During that time, the relief of the battalion serving in America – by the 4th – took place, and on the latter fell all Artillery duties performed at the commencement of hostilities in that country. As the war developed, the 4th Battalion was reinforced by four companies of the 3rd, whose men – and also the Lieutenant-Fireworkers – were gradually absorbed into the 4th Battalion. At the same time, four companies of the 1st and 3rd Battalions, under the gallant Phillips, were ordered to America, and formed part of the force commanded by the ill-fated Burgoyne. During this decade, between 1770 and 1779, five companies of the 2nd Battalion relieved those at Gibraltar, and were the only Artillery present at that memorable siege, which sheds a lustre over this unhappy period in the national history.

Woolwich saw a good many changes at this time. The barracks in the Warren were inadequate to meet the wants of the Regiment, now that it had received so many augmentations. Some ground on the Common was, therefore, purchased by the Board, and the foundation laid of barracks, large enough to accommodate a battalion of eight companies. The building was completed, and the barracks inhabited, early in 1776.

Modifications in the dress of the Regiment took place; and the evil results of the liberty granted to the Colonels of Battalions with regard to their men's clothing manifested themselves to such a degree, that in March, 1772, an order was issued, forbidding any alteration in the clothing of the men, or uniform of the officers, without the previous knowledge and approbation of the Master-General.

From various Battalion Orders issued at this time, we learn that the officers had now to provide themselves with plain frocks, and plain hats with a gold band, button, and loop; and that the accoutrements of the men, which had hitherto been buff, were now changed, – becoming what they are at present – white. The dress for a parade under arms was as follows: – The men, in white breeches, white stockings, black half-spatterdashes, and their hair clubbed: – the officers, in plain frocks, half-spatterdashes, and queues, with white cotton or thread stockings under their spatterdashes, and gold button and loop on their plain hats. When the officers were on duty, they were ordered to wear their hair clubbed, and their hats cocked in the same manner as those of the men. The hats of the men were worn with the front loops just over the nose. Black stocks were utterly forbidden, white only being permitted to be worn, either by officers or men.

On the 22nd June, 1772, a Royal Warrant was issued, deciding that Captain-Lieutenants in the Artillery and Engineers should rank as Captains in the Army. Those who were then serving, were to have their commissions as Captain, dated 26th May, 1772; and those who might be subsequently commissioned, from the date of their appointment. The title of Captain-Lieutenant was abolished, and that of Second Captain substituted, in 1804.

In 1772 and 1775, the regiment was reviewed by the King – on both occasions at Blackheath. The inspections were very satisfactory; in 1772, "The corps went through their different evolutions with great exactness, though greatly incommoded by the weather, and obstructed by the prodigious concourse of people, which was greater than ever was known on any like occasion." In addition to these reviews, the King visited Woolwich in state in 1773, for the purpose of inspecting the new foundry and boring-room. In the latter, he saw a 42-pounder bored with a new and wonderful horizontal boring-machine. He saw many curious inventions; among others, a light field-piece, invented by Colonel Pattison, "which, on emergencies, might be carried on men's shoulders," and which was tried, "to the great amazement of His Majesty." He also went to the Academy, where he breakfasted; and then inspected the companies which happened to be in Woolwich, with whose manœuvres he expressed the utmost satisfaction. The review was marred by an accident which occurred. "Colonel Broome, in parading in front of the Regiment, before His Majesty, on a very beautiful and well-broke horse, but very tender-mouthed, checked him, which made the horse rise upon his hind-legs, and fall backwards upon his rider, who is so greatly bruised, that his life is despaired of."24

In 1772, the officers, whose extra pay on promotion had been taken to make up the half-pay of Captain-Lieutenant Rogers, complained of the injustice, and their remonstrances were attended to. A warrant was issued on the 4th August, 1772, directing a vacancy of one Second Lieutenant to be kept open in one of the invalid companies, the pay to be employed towards Captain Rogers's half-pay.

It is impossible to stigmatize too harshly the system of non-effectives, borne for various purposes on the strength of the Regiment, in which the Board of Ordnance delighted. It was at once deceitful and unbusinesslike. If the purposes were legitimate, they should have formed the subject of a separate vote. At the risk of wearying the reader, a recapitulation will be given of the non-effectives in the Regiment at this time, and the purposes for which they were borne upon the establishment. There were thirty-two marching companies in the Regiment, and eight of invalids. On the muster-roll of each company, a dummy – so to speak – was borne, whose pay went to the Widows' Fund; another per company, for what was called the Non-effective Fund, and a third, whose pay went to remunerate the fifer. In addition to this, ten dummies were borne, whose pay went to swell General Belford's income, in the form of command pay; and nine were utilized for the band.

In short, out of 1088 matrosses, shown as the establishment of the marching companies, no less than 115 had no existence; and in the invalid companies, a Second Lieutenant and 16 matrosses were equally shadowy. If we examine the purposes for which the fund called the non-effective fund existed, shall we find them to be irregular, or such as could not be made public? Not at all; the charges on this fund were legitimate, and a separate vote might and should have been taken, particularizing them. They were to meet the expenses connected with recruits, deserters, and discharged invalids, as well as certain contingent charges, connected with the command of companies. Why then the mystery, and deceit practised upon the public? If the senior officer of Artillery was deserving of higher pay on account of his services or responsibility, why not openly say so, instead of showing to the country, as part of the Artillery establishment, ten men who had no existence? The wickedness and folly of such a means of keeping accounts could only have emanated from such a Department as the Board of Ordnance.

Mention has been made of recruiting expenses. Certain regulations which were in force at this time may be interesting to the reader. Levy money was not allowed to the recruiting officer in cases where the recruits were not approved by the commanding officer, but their subsistence after enlistment until rejection, was admitted. If a recruit deserted before joining, no charge whatever was admitted against the fund. But if he died between enlistment and the time when he should have joined, all expenses connected with him were admitted on production of the necessary vouchers and certificates. When the non-effective fund was balanced, which was done annually on the 30th June, 5l. was credited to the accounts of the coming year, for each man wanting to complete the establishment, in order to meet the expenses of the recruits who would be enlisted to fill the vacancies.

A word, now, about the invalids. They were for service in the garrisons; at first, merely in Great Britain, but ultimately also abroad, for in 1775, when the war in Massachusetts was assuming considerable proportions, the company of the 4th Battalion, which was quartered in Newfoundland, was ordered to Boston; and the two companies of invalids, shown as belonging to that battalion, and then quartered at Portsmouth, were ordered to Newfoundland for duty. Men over twenty years' service were drafted from the marching to the invalid companies, instead of being discharged with a pension; and the companies were officered from the regiment, appointments in the various ranks being given to the senior applicants.

In 1779, two additional invalid companies were added, and the ten were consolidated into one battalion, effective companies being given to the other battalions in their room.

The staff of the Invalid Battalion consisted of a Lieutenant-Colonel Commandant, a Major, and an Adjutant; and the establishment of each company was as follows: – a Captain, a First and Second Lieutenant, 1 Sergeant, 1 Corporal, 1 Drummer, 3 Bombardiers, 6 Gunners, and 36 Matrosses. Although this battalion was fifth in order of formation, and was frequently called the Fifth Battalion, – the real Fifth Battalion, the services of which are sketched in the end of this volume, was not formed until much nearer the close of the eighteenth century.

In 1772, a Military Society was founded at Woolwich for the discussion of professional questions. It was originated by two officers at Gibraltar – Jardine and Williams – extracts from whose letters to one another, when the idea occurred to them, are quaintly amusing. Lieutenant Jardine writes: – "I have been thinking that there must be a good deal of knowledge scattered about in this numerous corps. Could it not be collected, concentrated, and turned to some effect? We have already in this country all kinds of Societies, except Military ones. I think a voluntary association might be formed among us (admitting, perhaps, Engineers and others) on liberal principles, viz., for their own improvement and amusement, where military, mathematical, and philosophical knowledge, being the chief object of their enquiries, essays, &c., might thus be improved and propagated. They might thus communicate and increase their own ideas, preserve themselves from vulgar errors, and keeping one another in countenance, bear up against the contempt of pert and presumptive ignorance. If it increased in numbers, and grew into consequence, they might in time bring study and real knowledge into fashion, and, retorting a juster contempt, keep mediocrity, and false or no merit, down to their proper sphere."

His correspondent, who was then on board a transport, and wrote under difficulties, eagerly entered into the scheme, but for reasons stated could not go into details. "I have many things," he writes, "in my head, but our band (consisting of geese screaming, ducks quacking, hogs grunting, dogs growling, puppies barking, brats squalling, and all hands bawling) are now performing a full piece, so that whatever my pericranium labours with, it must lie concealed until I arrive at Retirement's Lying-in Hospital, in Solitude Row, where I shall hope for a happy delivery."

The friends reached Woolwich that year; and in October the society was formed. There happened to be many among the senior officers who sympathized with the promoters, notably Generals Williamson and Desaguliers, and Colonels Pattison and Phillips. The meetings took place at 6 P.M. on every Saturday preceding the full moon; and were secret, in order that an inventor might communicate his discoveries without fear of their appropriation. With the author's consent, however, papers might be published. The carrying-on of experiments was one of the main purposes which animated the society. At the present day, when the idea which animated the promoters of the old society has blossomed into a Literary and Scientific Institution, unparalleled in any corps in any land, which not merely encourages and developes the intelligence and literary talent of its members, but aids, in the highest degree, to lift the corps out of mediocrity into science, – these old facts connected with the infant society have a peculiar interest. The year 1872 may look back to 1772 with filial regard.

On the 8th July, 1773, the 4th Battalion arrived in New York – with the exception of one company, which went to Newfoundland.

Within a very brief period, the political atmosphere in that country became hopelessly overcast, and with the outbreak of the storm at Boston, in 1775, commences at once the active history of the American War, and of the Royal Artillery during that war, which is to be treated by itself. But parallel with that long and disastrous campaign, and occupying a period extending from 1779 to 1783, was the great siege of Gibraltar. To prevent an interruption in the thread of the American narrative, it is proposed to anticipate matters, and passing over the years 1775 to 1778, when the eye of the student can see nothing but America, proceed at once to the consideration of the siege, and then return to an uninterrupted consideration of the Artillery share in the American War from 1775 to the Peace of 1783.

CHAPTER XXV.

The Great Siege of Gibraltar

"Neither, while the war lasts, will Gibraltar surrender. Not though Crillon, Nassau, Siegen, with the ablest projectors extant, are there; and Prince Condé and Prince d'Artois have hastened to help. Wondrous leather-roofed floating-batteries, set afloat by French-Spanish Pacte de famille, give gallant summons; to which, nevertheless, Gibraltar answers Plutonically, with mere torrents of red-hot iron, – as if stone Calpe had become a throat of the Pit; and utters such a Doom's-blast of a No, as all men must credit." – Carlyle.

The year 1779 saw England engaged in war on both sides of the Atlantic, with bitter and jealous enemies. Her struggle with the revolted colonies offered a tempting opportunity to France to wipe out her losses during the Seven Years' War, – and to Spain, to wipe out the disgrace which she felt in the possession of Gibraltar by the English. France, accordingly, espoused the cause of the Americans; and Spain, under pretence of the rejection of an offer of mediation between England and France, proposed in terms which could not be accepted, immediately declared a war, which had been decided upon from the day of the disaster at Saratoga, and for which preparations had been progressing for some time without any pretence of concealment.