полная версия

полная версияHistory of the Royal Regiment of Artillery, Vol. 1

The Royal Artillery in this year consisted of thirty-two service companies, and eight invalid. The augmentation referred to in the last chapter did not take place until the end of the year. Of this number, one-half – sixteen companies – was in America; one company in Newfoundland; three in the West Indies; three in Minorca; and five in Gibraltar: – a total abroad of twenty-eight service companies out of thirty-two. Nor was it a foreign service, so weary and uneventful as it sometimes is now: it was a time when England was fighting almost for existence, and every company had to share the dangers. Should such a rising against England ever occur again, the Regiment could not select as its model for imitation anything nobler than the five companies which were in Gibraltar during the great siege.

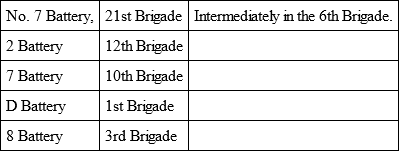

They were the five senior companies of the 2nd Battalion, and they still exist, under the altered nomenclature, as, —

At the commencement of the siege, Colonel Godwin was in command of the Artillery; but he returned to England in the following year, on promotion to the command of the Battalion, and died in about six years. He was succeeded by Colonel Tovey, the same officer who had been present with his company at Belleisle; and who, having had practical experience of Siege Artillery of the attack, was now to head a train of Artillery of the defence, in which duty and command he died. On his death, which happened at a most exciting period of the siege, he was succeeded by Major Lewis, whose conspicuous gallantry and severe wounds earned for him a well-deserved Good Service Pension.

The strength of the Artillery was wholly inadequate to the number of guns on the Rock. It amounted to a total of 25 officers, and 460 non-commissioned officers and men; whereas, at the termination of the siege, the following was the serviceable and mounted armament: —

Guns.– Seventy-seven 32-pounders; one hundred and twenty-two 24-pounders and 26-pounders; one hundred and four 18-pounders; seventy 12-pounders; sixteen 9-pounders; twenty-five 6-pounders; thirty-eight 4-pounders and 3-pounders.

Mortars.– Twenty-nine 13-inch; one 10-inch; six 8-inch; and thirty-four of smaller natures.

Howitzers.– Nineteen 10-inch, and nine 8-inch.

One of the first steps taken by the Governor, General Eliott, was to attach 180 men from the infantry to the Artillery, to learn gunnery, and assist in the duties of the latter. The regiments in garrison were the 12th, 39th, 56th, and 58th, also the (then) 72nd regiment. The (then) 73rd and 97th regiments joined during the siege. There were also 124 Engineers and artificers, and three regiments of Hanoverian troops. The total strength of all ranks in June 1779, was 5382; but it increased before the siege was over – by means of reinforcements from England – to 7000.

A few statistics connected with the Artillery and their duties may, perhaps, with advantage be prefaced to the account of the siege.

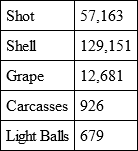

The amount of ammunition expended between September 1779|and February 1783, was as follows:

In all 200,600 rounds, and 8000 barrels of powder.

The preponderance of the number of shell over shot was caused by the use, during the siege, of shell from guns, with reduced charges – as well as from mortars and howitzers; suggested by Captain Mercier, of the 39th Regiment, and found so successful, as almost to abolish the use of shot during the first two years. In the year 1782, however, the value of red-hot shot against the enemy's fleet and works was discovered; the amount of shot expended rapidly increased; and while there was hardly a battery without the means at hand for heating them, there was also a constant supply, already heated, in the chief batteries.

The batteries from which the Artillery generally fired on the land side were those known collectively as Willis's; but when the fleet, and especially the hornet-like gunboats, commenced annoying the garrison, the batteries towards the sea had also to be manned, and the duty became so severe, that at times the fire had to be slackened, literally to allow the men to snatch a few hours' sleep.

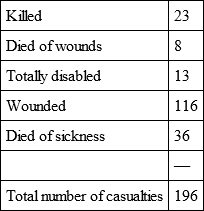

The proportion in the Royal Artillery of killed and wounded was very great. According to the records of the 2nd Battalion, the list was even heavier than that given by Drinkwater in his celebrated work; but even accepting the latter version as correct, it stood as follows: —

Out of a total of 485 of all ranks, there were: —

The officers who were killed were Captain J. Reeves and Lieutenant J. Grumley. The former commenced his career as a matross, and received his commission at the Havannah in 1762; the latter was a volunteer, attached in 1778 to the Artillery in Gibraltar, and commissioned in 1780; who enjoyed his honours for a very short time, being killed in the bombardment of the 13th of September, 1782. The officers who were wounded were Major Lewis, Captain-Lieutenant Seward, Lieutenants Boag, Willington, Godfrey, and Cuppage. Of these, Lieutenant Boag was twice wounded during the siege. He, like Captain Reeves, had commenced his service as a matross; nor was his promotion accelerated by brevet or otherwise on account of his wounds, in the dull times of reduction and stagnation, which followed the peace signed at Versailles in 1783. He was at last appointed Major in 1801. Retiring two years later, after a service of forty-five years, he died, as he had lived, plain James Boag, – unnoticed, forgotten, as the great siege itself was, in the boiling whirl which was circling over Europe, fevering every head and heart.

Two valuable inventions were made during the siege by Artillery officers, to increase the efficacy of their fire. By means of one, a gun could be depressed to any angle not exceeding 70° – a most important invention in a fortification like Gibraltar.

The other discovery – if it may be called so – was in an opposite direction. The nightly bombardment, in 1781, by the enemy's gunboats not merely caused great damage and loss of life, but also an annoyance and irritation out of proportion to the injury inflicted. Governor Eliott resolved to retaliate in similar fashion, and to bombard the Spanish camp, which it was hoped to reach by firing from the Old Mole Head. On it was placed a 13-inch sea-service mortar, fired at the usual elevation but with a charge of from twenty-eight to thirty pounds of powder; and in the sand alongside, secured by timber, and at an angle of 42°, five 32-pounders and one 18 pounder were sunk, and fired with charges of fourteen and nine pounds of powder respectively. The results were most satisfactory, – alarming and annoying the enemy, and in proportion cheering the garrison.

It was impossible that a siege of such duration could continue without the importance and responsibility of Artillery officers becoming apparent. This fact produced an order from the Governor, which saved them from much interference from amateur Artillerymen in the form of Brigadiers. The officers commanding in any part of the Fort were forbidden to interfere with the officers of Artillery in the execution of their duty, nor were they to give orders for firing from any of the batteries without consulting the officer who might happen to be in charge of the Artillery.

The life of the garrison during this weary siege was, as might be expected, monotonous in the extreme. The distress undergone, the want of provisions felt by all ranks, from the self denying Governor downwards; – the hoping against hope for relief; – the childish excitement at every rumour which reached the place; – the indignation at what seemed a cruel, unnecessary, and spiteful bombardment; – and the greater fury among the troops, when, among other results of the enemy's fire, came the disclosure in the damaged houses and stores of the inhabitants, of large quantities of wine and provisions, hoarded through all the time of scarcity, in the hope that with still greater famine the price they would bring would be greater too; – all these are told with the minuteness of daily observation, in the work from which all accounts of the siege are more or less drawn.

The marvellous contentment with which the troops bore privations, which they saw were necessary; the good-humour and discipline they always displayed, save on the occasion just mentioned, when anger drove them into marauding, and intoxication produced its usual effect on troops; the extraordinary coolness and courage they displayed during even the worst part of the bombardment, a courage which was even foolhardy, and had to be restrained; all these make this siege one of the noblest chapters in England's military history.

Although the blockade commenced in 1779, it was April, 1781, before the bombardment from the Spanish lines, which drove the miserable townspeople from their houses for shelter to the south of the Rock, can be said to have regularly commenced. When it did commence, it did so in earnest; shells filled with an inflammable matter were used, which set the buildings on fire; and a graphic description of a bombarded town may be found in Drinkwater's pages. "About noon, Lieutenant Budworth, of the 72nd Regiment, and Surgeon Chisholme, of the 56th, were wounded by a splinter of a shell, at the door of a northern casemate in the King's Bastion. The former was dangerously scalped, and the latter had one foot taken off, and the other leg broken, besides a wound in the knee… Many casks of flour were brought into the King's Bastion, and piled as temporary traverses before the doors of the southern casemates, in which several persons had been killed and wounded in bed… In the course of the day, a shell fell through the roof of the galley-house, where part of the 39th and some of the 12th Regiments were quartered; it killed two, and wounded four privates… In the course of the 20th April, 1781, the Victualling Office was on fire for a short time; and at night, the town was on fire in four different places… On the 21st, the enemy's cannonade continued very brisk; forty-two rounds were counted in two minutes. The Garrison Flag-staff, on the Grand Battery, was so much injured by their fire, that the upper part was obliged to be cut off, and the colours, or rather their glorious remains, were nailed to the stump… On the 23rd, the wife of a soldier was killed behind the South Barracks, and several men wounded… On the 24th, a shell fell at the door of a casemate in the King's Bastion, and wounded four men within the bomb-proof… The buildings at this time exhibited a most dreadful picture of the results of so animated a bombardment. Scarce a house north of Grand Parade was habitable; all of them were deserted. Some few near Southport continued to be inhabited by soldiers' families; but in general, the floors and roofs were destroyed, and only the shell left standing… A shell from the gunboats fell in a house in Hardy Town, and killed Mr. Israel, a very respectable Jew, with Mrs. Tourale, a female relation, and his clerk… A soldier of the 72nd Regiment was killed in his bed by a round shot, and a Jew butcher was equally unfortunate… The gunboats bombarded our camp about midnight, and killed and wounded twelve or fourteen… About ten o'clock on the evening of 18th September, a shell from the lines fell into a house opposite the King's Bastion, where the Town Major, Captain Burke, with Majors Mercier and Vignoles, were sitting. The shell took off Major Burke's thigh; afterwards fell through the floor into the cellar – there it burst, and forced the flooring, with the unfortunate Major, to the ceiling. When assistance came, they found poor Major Burke almost buried among the ruins of the room. He was instantly conveyed to the Hospital, where he died soon after… On the 30th, a soldier of the 72nd lost both his legs by a shot from Fort Barbara… In the afternoon of the 7th October, a shell fell into a house in town, where Ensign Stephens of the 39th was sitting. Imagining himself not safe where he was, he quitted the room to get to a more secure place; but just as he passed the door, the shell burst, and a splinter mortally wounded him in the reins, and another took off his leg. He was conveyed to the Hospital, and had suffered amputation before the surgeons discovered the mortal wound in the body. He died about seven o'clock… In the course of the 25th March, 1782, a shot came through one of the capped embrasures on Princess Amelia's Battery, took off the legs of two men belonging to the 72nd and 73rd Regiments, one leg of another soldier of the 73rd, and wounded another man in both legs; thus four men had seven legs taken off and wounded by one shot."

And so on, ad infinitum. The daily life was like this; for although even worse was to come at the final attack, this wearying, cruel bombardment went on literally every day. On the 5th May, 1782, the bombardment ceased for twenty-four hours, for the first time during thirteen months.

As in the time of great pestilence, after the first alarm has subsided, there is a callous indifference, which creeps over those who have escaped, and among whom the familiarity with Death seems almost to have bred contempt, so – during this long siege – after the novelty and excitement of the first few days' bombardment had worn off, the men became so indifferent to the danger, that, when a shell fell near them, the officer in charge would often have to compel them to take the commonest precautions. The fire of the enemy became a subject of wit even, and laughter, among the men; and probably the unaccustomed silence of that 5th of May, when the bombardment was suspended, was quite irksome to these creatures of habit, whose favourite theme of conversation was thus removed.

Among the incidents of the bombardment, there was one which demands insertion in this work, as the victim – a matross – belonged to the Royal Artillery. Shortly before the bombardment commenced, he had broken his thigh; and being a hearty, active fellow, he found the confinement in hospital very irksome. He managed to get out of the ward before he was cured, and his spirits proving too much for him, he forgot his broken leg, and falling again, he was taken up as bad as ever. While lying in the ward for the second time under treatment, a shell from one of the gunboats entered, and rebounding, lodged on his body as he lay, the shell spent, but the fuze burning. The other sick men in the room summoned strength to crawl out of the ward before the shell burst; but this poor fellow was kept down in his bed by the weight of the shell, and the shock of the blow, and when it burst, it took off both his legs, and scorched him frightfully. Wonderful to say, he survived a short time, and remained sensible to the last. Before he died he expressed his regret that he had not been killed in the batteries. Heroic, noble wish! While men like these are to be found in the ranks of our armies, let no man despair. Heroism such as this, in an educated man, may be inspired by mixed motives – personal courage, hope of being remembered with honour, pride in what will be said at home, and, perhaps, a touch of theatrical effect, – but, in a man like this brave matross, whose courage has failed even to rescue his name from oblivion, although his story remains – the heroism is pure and simple – unalloyed, and the mere expression of devotion to duty, for duty's sake. And this heroism is god-like!

This was but one of many heroic actions performed by men of the Royal Artillery. Another deserves mention, in which the greatest coolness and presence of mind were displayed. A gunner, named Hartley, was employed in the laboratory, filling shells with carcass composition and fixing fuzes. During the operation a fuze ignited, and "Although he was surrounded by unfixed fuzes, loaded shells, composition, &c., with the most astonishing coolness he carried out the lighted shell, and threw it where it could do little or no harm. Two seconds had scarcely elapsed, before it exploded. If the shell had burst in the laboratory, it is almost certain the whole would have been blown up – when the loss in fixed ammunition, fuzes, &c., would have been irreparable – exclusive of the damage which the fortifications would have suffered from the explosion, and the lives that might have been lost."25

Yet again. On New Year's Day, 1782, an officer of Artillery in Willis's Batteries, observing a shell about to fall near where he was standing, got behind a traverse for shelter. The shell struck this very traverse, and before bursting, half buried him with the earth loosened by the impact. One of the guard – named Martin – observing his officer's position, hurried, in spite of the risk to his own life when the shell should burst, and endeavoured to extricate him from the rubbish. Unable to do it by himself, he called for assistance, and another of the guard, equally regardless of personal danger, ran to him, and they had hardly succeeded in extricating their officer, when the shell burst and levelled the traverse with the ground.

This great siege of Calpe, the fourteenth to which the Rock had been subjected, divides itself into three epochs. First, the monotonous blockade, commencing in July, 1779; second, the bombardment which commenced in April, 1781; and third, the grand attack, on the 13th September, 1782.

The blockade was varied by occasional reliefs and reinforcements; and was accompanied by an incessant fire from the guns of the fortress on the Spanish works. The batteries most used at first were Willis's, so called (according to an old MS. of 1705, in the Royal Artillery Record Office), because the man who was most energetic, when these batteries were first armed, bore that name. When the attacks from the gunboats commenced, the batteries to the westward – the King's Bastions and others – were also employed. The steady fire kept up by the Artillery, its accuracy, and the improvements in it suggested by the experience of the siege, were themes of universal admiration; and the many ingenious devices, some of them copied by the enemy, by which, with the assistance of the Engineers, they masked, strengthened, and repaired their batteries, form a most interesting study for the modern Artilleryman. The incessant Artillery duel, which went on, made the gunners' nights as sleepless frequently as their days; for the hours of darkness had to be devoted to repairing the damages sustained during the day. Well may the celebrated chronicler of the siege talk of them as "our brave Artillery," – brave in the sense of continuous endurance, not merely spasmodic effort.

At the siege of Belleisle, described in a former chapter, the failing ammunition of the enemy was indicated by the use of wooden and stone projectiles. The latter were used by the Royal Artillery at Gibraltar, but for a different reason. To check and distract the working-parties of the enemy, shell had been chiefly employed by the garrison; and the proficiency they attained in the use of these projectiles can easily be accounted for, when it is remembered how soon and how accurately every range could be ascertained; how eager the gunners were to make every shot tell; and how exceedingly important it was to check the continued advance of the enemy's works. For variety's sake, it would seem, for there was no need to economize shell at this time – in pure boyish love of change, the Artillerymen devised stone balls, perforated so as to admit of a small bursting-charge, and a short fuze; and it was found that the bursting of these projectiles over the Spanish working-parties caused them incredible annoyance.

Although the fire of the garrison during the first epoch of the siege was the most important consideration, and its value could hardly be overrated, as to it alone was any hope due of prolonging the defence until help should come from England, – it was not the only distinctive feature of this time. It was during the blockade that the garrison was most sorely tried by the scarcity of food. And in forming our estimate of the defence of Gibraltar, it should never be forgotten that the defenders were always the same – unrelieved, without communication with any back country; and with hardly any reinforcements to ease the heavy duties. The 97th Regiment, which arrived during the siege, was long in the garrison before it was permitted, or indeed was able, to take its share of duty; and the hard work, as well as the hard fare, fell upon the same individuals.

The statistics, given so curtly by Drinkwater, as to the famine in the place, enable us to realize the daily privations of the troops. At one time, scurvy had so reduced the effective strength of the garrison, that a shipload of lemons which arrived was a more valuable contingent than several regiments would have been. In reading the account of this, with all the quiet arguments as to the value of lemon-juice, and its effect upon the patients, one cannot but wish, that in every military operation there were artists like Drinkwater to fill in the details of those pictures, whose outlines may be drawn by military commanders, or by the logic of events, but whose canvas becomes doubly inviting through the agency of the other industrious and unobtrusive brush. Modern warlike operations suffer from an overabundance of description; but the skeleton supplied by official reports, and the frequent flabbiness of those rendered by newspaper correspondents, produce a result far inferior to the compact picture presented by a writer at once observant and professional.

In a table, at the end of Drinkwater's work, crowded out of the book, as if hardly worthy of mention, and yet most precious to the student now, we find some of the prices paid for articles of food during the siege. Fowls brought over a guinea a couple; beef as much as 4s. 10d. per pound; a goose, 30s.; best tea as high as 2l. 5s. 6d. per pound; eggs, as much as 4s. 10½d. per dozen; cheese, 4s. 1d. per pound; onions, 2s. 6d. per pound; a cabbage, 1s. 7½d.; a live pig, 9l. 14s. 9d.; and a sow in pig, over 29l.

The high price, at times, of all vegetables, was an index of the existence of that terrible scourge – scurvy.

Some very quaint sales took place. An English cow was sold during the blockade for fifty guineas, reserving to the sellers a pint of milk each day while she continued to give it; while another cow was purchased by a Jew for sixty guineas, but in so feeble a state, that she dropped down dead before she had been removed many hundred yards. The imagination fails in attempting to realize the purchaser's face – a Jew, and a Gibraltar Jew; but can readily conceive the laugh against him among the surrounding crowd, their haggard faces looking more ghastly as they smiled. Although Englishmen take their pleasure sadly, they also bear their troubles lightly. An English soldier must be reduced indeed, ere he fails to enjoy a joke at another man's expense, and this characteristic was not wanting at Gibraltar.

The second epoch – the Bombardment – was at first hardly believed to be possible. The fire of the garrison was directed against an assailant and a masculine force; but a bombardment of Gibraltar meant – in the minds of its defenders – a wanton sacrifice of women and children; a wholesale murder of unwarlike inhabitants, who could not escape, and to whom the claims of the conflicting Powers were immaterial. The wailing of women over murdered children, of children over wounded parents; the smoking ruins of recently happy homes; the distress of the flying tradespeople and their families, seeking safety to the southward of the Rock, and abandoning their treasures to bombardment and pillage; all these told with irritating effect upon the troops of a country whose sons are chivalrous without being demonstrative. In days coming on – in terrible days which many who read these pages may have lived in and seen, English troops shall clench their hands, and set their teeth with cruel hardness, as they come upon little female relics – articles of jewellery or dress – perhaps even locks of hair, scattered in hideous abandonment near that well at Cawnpore, whose horrors have often been imagined – never told. To those who have seen this picture, the feelings of the beleaguered garrison in Gibraltar will be easily intelligible, as they stumbled in the town over a corpse – and that corpse a woman's. No wonder that when the great sally took place, historical as much for its boldness as its success, there was an angry desperation among the troops, which it would have taken tremendous obstacles to resist. It was a brave morning, that 27th of November, 1781, when "the moon's nightly course was "nearly run,"26 and ere the sun had risen, a little over 2000 men sallied forth to destroy the advanced works of the enemy – an enemy 14,000 strong – and works, three-quarters of a mile from the garrison, and "within a few hundred yards of the enemy's lines, which mounted 135 pieces of heavy artillery."[28] The officers and men of the Royal Artillery who took part in the sortie, numbered 114; and were divided into detachments to accompany the three columns of the sallying force, to spike the enemy's guns, destroy their magazines and ammunition, and set fire to their works. It was the last order issued in Colonel Tovey's name to the brave men whom he had commanded since the promotion of Colonel Godwin. For Abraham Tovey was sick unto death; and as his men were parading for the sortie, and the moon was running her nightly course – his was running fast too. Before his men returned, he was dead. For nearly half a century he had served in the Royal Artillery – beginning his career as a matross in 1734, and ending it as a Lieutenant-Colonel in 1781. He died in harness – died in the command of a force of Garrison Artillery which has never been surpassed nor equalled, save by the great and famous siege-train in the Crimea.