полная версия

полная версияDactylography

When we first encounter remains of man or his close predecessor in the records of the rocks, he was a dweller in holes and caves of the earth. He certainly did not make pots of any kind, or at least he has left no such remains. Probably he had no such companions even as the domestic dog or cat, no cattle, not at first any kind of grain crop. He lived on roots and fruits, hunted, and fished. Those early people have often been called Troglodytes, from the Greek τρώγλη, a cave.

Professor Keith, the learned curator of the museum of the Royal College of Surgeons, has advanced the theory that about the middle of the Miocene Age a group of creatures existed, having affinities to man as he now is, which group the professor names Proto-troglodytes. From these sprung three classes of Troglodytes, namely:

The Gorilla;

The Chimpanzee;

Man.

Some eighty-seven anatomical features are said to be possessed by the gorilla in common with man only, while the chimpanzee has ninety-eight such features as belong to man. The gorilla has the best and biggest teeth, and in this respect progressive deterioration went on through the orang-utan and the chimpanzee to man. According to the estimate of Professor Keith, there are not in the whole world, at present, more than 100,000 chimpanzee, and some 10,000 gorillas.

The subject of twins is likely in future to be very interesting in relation to the resemblance of their finger-patterns. The distinction is now made of twins proceeding from one zygote or fertilized ovum, and twins proceeding each from different fertilized ova. In the first case, it is supposed that the twins are necessarily of the same sex, while in the other, each twin child may be of the sex determined by the fertilized ovum from which it sprung. Clearly, in the latter case it might often happen that both twins might be male, or both female.

Dr. Berry Hart quotes from the records of another observer (Wilder) in which there was a pair of “identical” twins, in whom the similarity was complete even to the finger-prints. [Brit. Med. Jour., July 29th, 1911, p. 215.] I have found in the same family male and female with resembling finger-prints, but none which could be called identical, but opportunities of comparing twins of the same sex do not often occur. While writing this chapter I examined twins of the same sex (female). Their finger-prints are very similar, but details diverge in many directions. The matter merits close attention. But how are we to determine that twins of the same sex are from one ovum, seeing that there might be a coincidence of twins of the same sex proceeding from separate ova? If their finger-prints are “identical,” is that the main evidence? or do identity of features, colour of hair, voice, manners, and character, come up independently? If one questions the theory, the “identity” must be very complete indeed, to give it vraisemblance, for how often do we not find that children of the same parents, not twins, but born with many years intervening, show most striking resemblance? The alleged complete identity of finger-patterns, however, is a most interesting and novel point, and ought to receive close attention from parents and physicians. A curious fact about hereditary resemblance is this, which I have frequently observed. A child resembles, say, a mother as a rule, but at some emotional, angry, or vexed moment, lines are marked in the face by muscular movements which bring out like a mask a striking likeness, say, of the father, or of some other progenitor. Besides this, a child at different stages may resemble in succession different near relatives, and in a very striking degree resemble them. But with regard to finger-patterns there is no such variability. Even a month or two before a child is born its little heraldic crest begins to be firmly fixed for each finger, as it is to be throughout life.

The disease called Acromegaly, or giant growth, involves great expansion of the ridges and furrows, but no case of actual change of patterns has been observed as yet. The attention of medical men should be given to this affection in regard to modification of linear arrangement.

The likeness or divergence of finger-patterns in neighbouring supernumerary fingers and toes might yield interesting results if carefully recorded. Extra fingers are commoner than extra toes. The webbing of fingers, as in the chimpanzee, might also be noticed, and any association with retrograde patterns, in the fingers concerned.

The rapid growth of a literature of Criminology is partly the result of better methods of identification. It is unscientific to reason about the personal peculiarities of all the Toms, Dicks, and Harrys, when Tom may be Dick, or Dick Harry under a different alias. The criminologist can now use his prison statistics as to age, habits, and the like, with much greater confidence and precision. In an interesting, but somewhat reckless work on “Criminal Man,” which summarizes the teaching of the eminent Italian authority on the anatomy and psychology of the criminal – of the Italian criminal at least – Cesare Lombroso, we are told (p. 20): “Long fingers are common to swindlers, thieves, sexual offenders, and pickpockets. The lines on the palmar surfaces of the finger-tips are often of a simple nature, as in the anthropoids.” But they are not, necessarily, of a simple nature in the anthropoids, but often highly ornate and complex in their ramifications. In the lower monkeys they are much simpler, and Sir F. Galton thought it was so sometimes in the negro peoples. Indeed, one is not surprised to meet such simple lineation patterns now and again in cultivated people, without any criminal taint, or negro blood, or any anti-socialistic tendencies that can be easily detected. A cautious prison doctor in Glasgow, Dr. Devon, has written a clever book which gives much food for sober reflection. He seems to say that the criminal is not a kind of species by himself: “If those who come to prison for the first time were made the subject of examination, it would be found that they are principally remarkable for the absence of what the books call criminal characteristics.” (p. 11.)

CHAPTER V

TECHNIQUE OF PRINTING AND SCRUTINIZING FINGER-PATTERNS

There are important points connected, with the printing of finger-patterns, especially for legal investigation, which come now to be considered. A human finger, as we have seen, is not, for printing purposes, just like a lithographic stone, a box-wood engraving, or a plate of zinc, steel, or copper. In ordinary printing, especially of high-class and delicate engravings, the quality and fluency of ink, the smoothness of surface and hygrometric conditions of paper – due sometimes to local atmosphere, and sometimes to climate generally – the skill of workmen, all the conditions co-operate in producing variations, slight it may be, but noticeable in the results obtained. In the case of finger-prints we might also have to consider the willingness or unwillingness of the subject having his finger-prints officially taken. A finger – even that of a dead person – is compressible, while retaining on the whole the pattern of its furrows and ridges, and hence under fairly similar conditions, the printed products may be somewhat different in appearance. The same fact would apply, no doubt, also to impressions taken from an indiarubber stamp, made, we shall suppose, for stamping purposes in regard to documents, in imitation of a particular finger-print pattern. Greater compression tends to flatten out the ridges and to narrow the intervening grooves, while it may also tend, especially when associated with over-inking, to obliterate some of the characteristic ramifications of the pattern. But, again, the finger of a living person is usually in a state of physiological activity. It swells or shrinks, drying up or exuding moisture from its many pores, which facts, however minute and insignificant they may appear to the uninstructed, to the trained dactylographer they leave a most interesting and significant record behind.

Examine carefully a ridge which has been printed – and, if possible, photographically enlarged – at various periods not long apart, and the pores with which it is dotted will be found, while retaining their relative positions, to vary somewhat in their degree of patency. A single ridge might be compared to a naval cruiser, the numerous funnels of which are not all belching forth smoke at the same time, but one is almost smokeless while its neighbour is quite active. Those pores which have been copiously emitting sweat are seen, when imprinted, to be larger than those that were inactive. An imaginary case was once suggested to me as a final blow to finger-print identification. A certain Mr. William Sykes is officially known to be recruiting his valuable health at one of His Majesty’s sanatoriums for people of his profession. That celebrated artist’s “thumb”-print, however, has been found liberally spotted all over the scene of some tragic area of crime. What is to be said? Well, the prodigality of display of the well-known sign-manual, in circumstances when gloves are almost invariably now worn by experts, might well arouse suspicion in itself, but it would easily be found in such a case that the pattern had been prodigally repeated with too great fidelity in the matter of sweat-pores, which, in the case of an active burglar, who is a sober, hard-working fellow in spite of his faults, would vary with each successive imprint, in a way that no manufacturer of bogus “thumb”-prints could easily follow.

The fact that a finger – a clean finger – is naturally, to some slight extent, greasy, partly from sebaceous secretion, enables the expert dactylographer by various chemical and mechanical means to obtain a pretty clear vision, even in minute detail, of what before had been quite invisible. A mere accidental smudge from a slightly oily palm or finger, if imprinted on glass, japanned tin, varnished or polished wood, etc., may have its invisible lineations brought out by dusting gently upon it some light powder of appropriate colour. Dr. René Forgeot, in 1891, first called attention to this method of bringing out latent imprints, and my friend, Dr. Garson, of this country, gave it further developments.

In my Guide I have mentioned some of my own results with modifications of these methods.

On a pane of glass which a malign finger is suspected to have touched, a fine black powder gives vivid and beautiful results, the sooty matter clinging to and revealing the oily surface of the lineations in very full detail. In my article in Nature of 1880 a sooty imprint is shown to have helped an innocent man to establish his innocence, but in this case the imprint was quite direct. The powder should be gently blown over, or dusted lightly on to the greasy impression, with a soft camel hair brush which is perfectly clean and dry. Care should be taken not to breathe on the glass, or a damp, smeary effect may result. I have not found sable brushes act so well as those made of camel hair, a fact which their structure under the microscope helps to explain. (See frontispiece.)

The best treatment of a greasy smudge on a dark ground, say the surface of a japanned cash-box, marble slab, school slate, or enamelled door panel, is carefully to dust over the object with a fine white powder, such as the ordinary tooth-powder of the chemists, or still better, as I find, with the light carbonate of magnesia. In one sense this may be said to yield a negative print, but an important qualification arises. The patterns now in white are the ridges which before were black, while the furrows remain dark as at first. In a smoked glass print the white ridges have not imparted something to the glass, but have simply removed the carbonaceous deposit previously there. Practically, however, the whitened ridges have the quality of a negative imprint, as previously described.[D]

Greasy finger-marks may also be acted on chemically, so as to bring out details by the application of osmic acid. If there is any olein or oleic acid in the mark, as there generally is in human finger-marks, the acid deepens the tone of the almost invisible lines into a brownish hue, revealing all their richness of detail. I have succeeded in etching finger-marks of this kind on glass by means of hydro-fluoric acid. They remain quite indelible in all their details so long as the glass itself endures. The patterns thus etched can be very well brought into view by painting a dark background on the reverse, or pasting dark paper behind. There is a clear layer of the skin in both palms and soles, the fat of which is eleidin. That particular kind of fat does not stain with osmic acid in the usual way. The sweat of palms and soles is not supposed to contain any fat at all, but there would seem to be some faint trace of it in sweat. The greasy surface of the skin as a rule comes from the sebaceous glands, as previously described. When clean palms leave a greasy smear, as they often do, I think the greasiness must generally come by transmission from other parts of the body, or from contact with foreign greasy substances, which are common enough.

For those who wish to study dactylography, the apparatus is neither complicated nor expensive. A good pair of compasses, a botanical lens, a school slate or tin plate or porcelain tile, a small pot of fine printer’s ink, and an ink-roller or photographer’s “squeegee” will suffice for most purposes. For the expert who must make fine measurements of enlarged photographs, and perhaps defend them under keen forensic criticism, one or two instruments are required, presently to be described.

The ink may be daubed evenly and thinly on the slate, tile or plate, but it is better to use a small printer’s roller for the purpose. Avoid all fluff, hairs, or grit, which thoroughly spoil any print. The roller should always be scrupulously cleaned before laying aside, and it is well to provide a tin case for its reception. The remaining stock of ink should be carefully levelled a-top, and covered with a drop or two of linseed or other oil, which will preserve it in good and workable condition for a long time. Reeve’s Artists’ Depôts, Ltd., 53 Moorgate Street, London, supply an excellent quality of ink for this purpose, in flexible tubes, at sixpence each, and the same firm can generally provide the rollers or squeegees used by photographers, which serve very well. In an emergency I have made serviceable ink with burnt cork, lamp soot, even shoe-blacking, using a good smooth and even cork as a roller. Wax casts, which should occasionally be made for study, can be made with the sheets of wax used greatly, at one time, for the making of artificial flowers. Excellent casts can also be made with putty, gutta-percha, sealing-wax, or hard paraffin, such as is used to encase the modern candle. Very excellent imprints of this kind have been left by burglars on candles they have used.

Some useful practical hints as to how finger-prints may be photographed and enlarged for police purposes are supplied by Inspectors Stedman and Collins, in an official work by Sir E. R. Henry, Classification and Uses of Finger-Prints; and others occur in Daktyloskopie, published in Vienna. Finger-marks on plated articles, when placed squarely with the camera in a strong side light, will appear light on a dark ground. The instructions in such a case are: “Focus sharply. Should, however, the mark be too faint to be clearly seen on the focussing screen, a piece of printed paper can be placed around the mark to focus by, but this should be removed before exposing the plate, otherwise halation will set in and obscure some of the lines in the finger-mark.” The plate done in this way gives a negative result, so that a transparency must be made and used so as to convert that into a positive print.

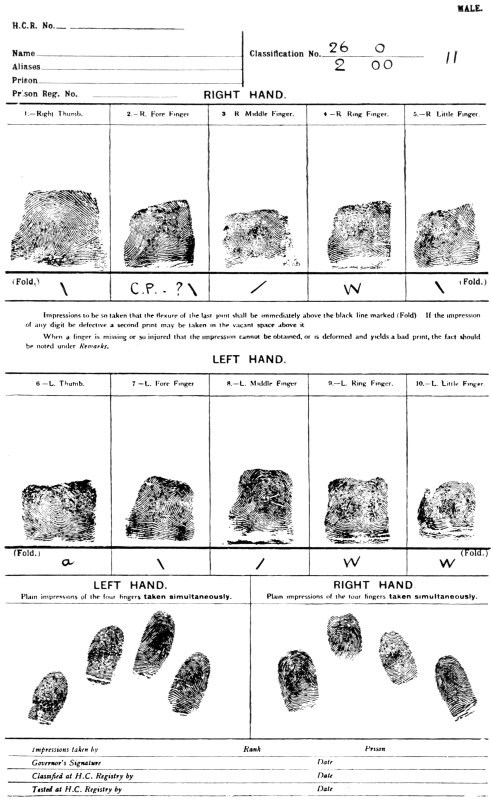

The fingers and thumbs may each be printed separately. For identification the serial order of fingers must be retained on the record. The official method in England is to print four fingers of each hand simultaneously, adding the right and left thumb to each respective section of the register. In addition, each thumb and finger is imprinted by rolling it slightly, which gives an enlarged area for the display of the more important linear elements in each finger pattern.

The prisoner signs this sheet, and also adhibits an imprint from his right forefinger under the signature.

The highly-glazed papers now so much used for half-tone photographic reproductions are not, in my experience, particularly good for ordinary impressions. The surface of any paper used should be fairly smooth, the texture firm, tough (not brittle), durable, and the colour white, as photographs for enlargement as judicial exhibits may be required.

Great care is now taken officially to secure the correct order of fingers, as on that the validity of the method depends, and the whole utility of the classification.

Inspectors Stedman and Collins, in the work just quoted, state that when finger-prints are required to be produced as evidence in a court of justice, “they are first enlarged 5 diameters direct with an enlarging camera. The negatives are afterwards placed in an electric light enlarging lantern, with which it is possible to obtain a photographic enlargement of a finger-print 36 inches square, such a photograph being as large as is ever likely to be required.”

In my Guide to Finger-Print Identification (p. 62) I have advocated uniform enlargement of all such exhibits on the decimal or metric system, and hope that international agreement on this point may be secured. Apart from criminal services its scientific utility would ultimately be very great. The objection that an English jury would dislike being confronted with the technicalities of a foreign and “mathematical” system is very easily met. An English jury – and no jury in the world is fairer or clearer-headed – would only, in any case, have to compare two figures similarly enlarged, one being that of the accused person’s fingers, taken while in custody, and the other, either a similar official record of another date, or a smudgy mark from some blotting-pad, window-pane, drinking-glass, bottle, or the like. The two exhibits, paired for comparison, would have been enlarged exactly on the same scale, whatever that scale might have been. For purposes of judicial comparison, therefore, English terms and English instruments might be used throughout, and no inconvenience could be felt by the most insularly prejudiced jury that could possibly be got together.

When a photographic enlargement has been made, it is necessary to be able readily to test its conformity with the enlargement to be compared with it, or if there be not strict agreement, to allow for and calculate the admitted discrepancy. This may easily be done by an application of the “rule of three.”

Reduced Copy of Police Register Form

Reverse Side of Form

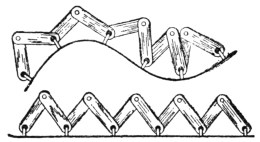

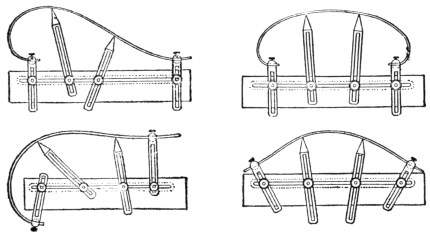

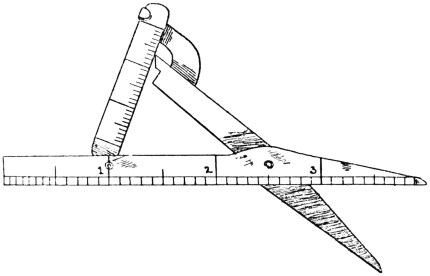

It may be necessary to test the concurrence of curved lines in two exhibits similarly enlarged. At one time I used strips of plumber’s lead, placed edgeways on the curved lines to be compared. They could be flexed so as to show the various sinuosities, however complex, but leaden tapes cannot readily be made to retain the form imparted to them. Copper wire I found to be stiffer, but it readily warps off the plane. An excellent way is to draw on transparent paper a line corresponding to the curved line seen underneath. The transparency is then transferred and adjusted to the other enlargement, the curves of which should be seen to be congruent. The instrument called “flexible curves” which is used by engineers and mechanical draughtsmen I at last tried, and found it to be exceedingly serviceable for such comparisons. The pattern “B,” self-clamping, 12-inch size, is for most cases the most suitable. Other patterns are made also, in sizes of 9 and 18 inches. The “B” pattern has a flexible steel strip, like the lead tape just mentioned. After the curve or series of sinuosities has been adjusted correctly, the shape is rigidly retained by means of a stiff-hinged link-work arrangement attached by tabs. The strip of steel should not be pressed down between two tabs, and when bending or straightening out the instrument one should do so bit by bit, beginning at one end and continuing onwards from there. This useful self-clamping instrument used to be supplied by Mr. Wm. Brooks, scientific instrument maker, 33 Fitzroy Street, Tottenham Court Road, London. Another instrument of this kind, the “Curve Rule” is sold by Mr. W. Harling, 47 Finsbury Pavement, E.C., and is figured here.

Flexible Curves.

Harling’s J. R. B. Curve Rules.

In dealing with such approximate curves as one finds among the lineations of finger-prints, one is not supposed to apply strictly mathematical principles. The lines, for example, have breadth, but not quite invariable breadth. We must, therefore, avoid treating them, as a beginner fresh from the schools is apt to do, as ideal concepts. The simpler terms, however, as used by a teacher of drawing, with the provisos already hinted at, will serve very well to guide one’s efforts, or to explain one’s own conceptions before a magistrate or a jury.

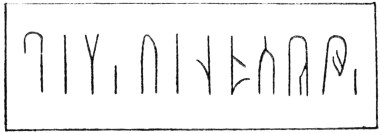

Besides the congruity of the curves, one has further to test the single lineations, their junctions, number, and character. An excellent way to envisage these is to make alternate linings with blue and red pencil, to represent them as they seem. To do this effectively one may single out a special measured square, or circle, or parallelogram, of the enlarged figure. Proceed then, quite ignoring, if need be, all great curvatures, to consider the lines as simple curved or straight lines, and analyse them into composing elements, like twigs of a tree or the characteristics of a runic alphabet. The result will be, perhaps, like the figure on the next page.

It will now be quite easy to orient, or place correctly in space, the corresponding part of the other print – if it really does correspond – and a similar “rune” should result. One may afterwards follow out each recognized lineation into further complexities or joinings, as you might trace out a railway line with its various junctions in a map.

Diagrammatic Analysis of Lineations in a Restricted Section.

A photographic enlargement, meant for forensic use, ought not to be marked or soiled in any way, but dots of coloured chalk or ink might be placed along the margins to denote where imaginary ruled lines might begin or end. One might also use glazed tissue paper, ruled in squares, or with eccentric circles like the mileage lines in a map of London. By the use of these placed over the figure one might verify particular coincidences or demonstrate discrepancies.

When the skin-pattern is impressed upon soft sealing-wax, clay, putty, and so on, the relievo image produced is different in this way from an ordinary ink-printed pattern. The convex ridges are now concave furrows, while the hollows are changed into heights.

In both kinds of impressions a reverse or mirror pattern is produced, a matter of some practical importance. This effect may, or may not again be reversed in the photographic process. It is not impossible, in such circumstances, that a suspect’s finger might be confused with a resembling “mirror” pattern, which was really not his own.

I have thought that the word verso, used technically for the reverse of a coin or medal, might be usefully employed in dactylography for the reverse or mirror image of a finger-pattern when printed. A technical word for the indented impression made by a finger on wax and the like is also wanted. Now geologists use -lite as a terminal to express the impression or cavity which had been formed in a rock, when soft, by the impressed body of an organism. Hence the word dactylolite might be used to denote an indented impression of a finger.

Kew Micrometer.