полная версия

полная версияDactylography

It will be noticed, perhaps, that the syllable bra occurs twice on the same hand register. It by no means follows that the finger-print represented by the second bra is very like that of the first one. In the same way, none of the patterns indicated by bra in the cards of similar syllabic index may much resemble the others, even broadly. The pattern simply is of a certain typical form with which bra is to be linked for registration purposes. The same word, so to speak, might be divided in a different syllabic way, thus: —

Ab-ra-cad-ab-ra;Ab-rac-ad-ab-ra; and so on.Hence the necessity of separating the syllables by hyphens.

The divergence of cards will be greater, of course, in the case of a two-hand register, and even in one which comprehended, say, one million of complete sets there would be very few repetitions of the same arrangement of syllables.

One great advantage of the syllabic form is the help given to the memory in transferring the eye from one sheet to others which may be wanted. In the system now in use the symbols do not rivet themselves in the same way, and have a monotony that becomes very tiring.

A general view of the precise intention aimed at in the particular register must determine the extensiveness of the form the register is to compass. Are the numbers likely to be large? Must the registers extend over long periods? Are infants to be kept in view over adult life, if that is reached? Many enquiries of this kind may have to be met before the exact form of the cards or sheets is determined. For such civil and social purposes as life insurances, signatures of deeds, benefit of friendly societies, and the like, a comparatively simple form of register and limited number of finger imprints might be all that would be required for an effective service. The number of cards would not be very great, and the probabilities of personation would likely be restricted to a few local residents whose finger-prints would not often be found even to approach coincidence in a slight degree. To serve such needs, an elementary form of classification would go a long way to overtake ordinary requirements, and would be easy of reference. Few of the difficulties involved in graver conditions of legal identification need be raised as an objection to the general use in banking and ordinary business of this new mode of identification. In forming a system, even with a very wide range, the whole amount of possible complexity in finger-patterns need rarely be called upon, and could not conceivably be exhausted. I speak confidently on this point. The central part of the pattern used is generally very limited, and its area may be widened whenever an enlargement of the primary requirements may demand more complexity in the factors of identification. The ramifications will usually provide variety enough to satisfy the most avaricious register.

Some of the main conditions on which the problem of alphabetic arrangement of the index depends may now be set forth, before we proceed to consider how those conventional syllables are to be formed which indicate patterns.

1. – Distinction is not made between capital and lower-case letters. Simple letters are too soon exhausted in a register of any considerable size. It is obvious that syllables give a much greater variety. As far as possible, commensurate with the dimensions of the register, the syllables should be kept few, simple, compact, and pronounceable. The vowels have the Italian sound. No syllables should contain more than four letters at the utmost.

2. – When a doubt arises as to the proper syllabic reading of a finger-pattern, the earlier letters of the Roman alphabet have the precedence, thus b before d, l before x.

3. – Where the core of a pattern seems to contain two or more clusters of significant lineations, choose for the index syllable that on the right side of the pattern, or, if that is difficult to determine, next that which is highest in position. In such a case, reference to orientation or position refers to the usual or official pattern. In dealing with a smudge of unknown origin, the various possibilities may be tried, assuming relative order of position, as above.

4. – When spaces or figures, such as ovals or circles, are described as “large,” that means wider than the space occupied by two average lineations in that finger-print.

5. – When a finger-pattern has been permanently defaced or obliterated by injury or disease, the missing mark may be denoted by an asterisk (*). If the finger itself is missing, by deformity or mutilation, the asterisk may be encircled with an O. A special compartment of the register might be kept for the reception of all such cases.

6. – Badly-printed or obscure patterns should be held in reserve under a special register classified according to probabilities, aided by cross indexing, and receiving special attention from the higher experts. Official patterns badly printed should at once be repeated, if possible, before confusion arises.

7. – Registers for naval or military, and banking, insurance, and general purposes, should be kept strictly free from any police supervision or control.

The syllables in my system, viewed as lexicographic elements, consist of the ordinary Roman vowels and consonants, the vowels being pronounced, as already said, as in the Italian language. I hold in reserve for additional official purposes a few additional characters, such as the Greek letter delta Δ. Those, however, need not be dealt with in the brief space now available, and would only be required, I believe, in pretty extensive registers. The functions of the conventionally fixed vowels may be better understood after we have sampled a few of the consonants.

As suggested to me by Sir Isaac Pitman’s system of phonography, learned in student years, I arranged the consonants in co-related pairs, thus: p, b; t, d; s, z; h, f; l, r; k, g; v, w; ch (considered as a consonantal character), j; m, n.

I have already pointed out, in dealing with problematic smudges, the need of understanding patterns apart from their actual orientation, which, in an unknown person’s case, may have to be assumed, an attitude which may be determined by official bias. This I have entered more fully upon in the Guide to Finger-Print Identification.

Holding this principle in view, then, let us now take some of the simpler elements of patterns in their very simplest forms, and first consider those grouped under the paired consonants.

Ch and JEach of these characters is taken to represent a hook with a short leg. Ch is considered as one consonant, and as C is not otherwise wanted, it might have been used alone but for its pronunciation being indefinite. If in the usual form of official imprint the hook, with its curve below, has its short leg facing to the left, thus, J, it is duly represented by the Roman letter of that shape. Observe that if you invert this character, or the type which represents it, thus

If the short leg of the figure points to the right it comes under Ch. If that happens to confront one in its inverted position it cannot be mistaken for a J figure, but must be looked for under Ch. In all cases the degree or direction of slope in the figures, with a few peculiar exceptions, is of no concern whatever, simplicity and directness of appeal being aimed at from the first.

B and PThese consonants are used to denote a bow. B is the form of a simple bow with one lineation, or if two or more lineations blend into one, they are found on the left side when the convexity of the curve is upwards. P is such a bow, but strengthened, as it were, by one or more blended lineations on the right side, with the same position of the curve. A single line bow is never represented by P. If a bow with a plurality of blended lineations is inverted the reading is not at all affected.

T and Drepresent pear-shaped, or battledore-like figures. T denotes such a figure free from attachment to environing lineations, while D stands for a similar figure fixed by its stem. Reverse the position of the figure or turn it upside down and its index quality is not affected.

K and Grepresent spindle-like forms, like the above but with two (opposite) stems instead of one. When the figure is moored by one stem it is denoted by K; when fixed at both ends or free at both, by G. Position does not affect these figures.

V and WThese letters stand for whorls or spirals, a kind of figure that often presents much difficulty in finger-print classification. W is a whorl in which, tracing its course from the centre outwards, the pen goes round as a clock-hand turns, or as one looking towards the south perceives the sun to cross the sky. V, on the other hand, is one which, traced in the same way (from within outwards), the pen goes like the clock-hand backwards, or widdershins. Alteration in position makes no practical difference whatever in the reading of those figures into their proper syllables for an index.

O and QAlthough O is a vowel and will be met with again under that class, it is paired in a kind of way with Q.

O denotes a small circle or oval, or opaque, round, or ovoid dot, contained in the core of a pattern.

Q denotes a large circle or oval, containing, usually within itself, other pattern elements of small dimensions.

A circle or ovoid is called large when it occupies a space wider than two average lineations of that finger-pattern in which it occurs. If any doubt exists, by the principle previously mentioned, the figure is referred to O as prior to Q in alphabetical sequence.

M and Ndenote figures somewhat resembling mountain peaks, M signifying an outline like that of a typical volcanic peak, while N, though similar, ends in a rod-like form, as of a flag-staff on a mountain top. Invert either of those typical forms and they can be read as before.

A curved cliff-like form, like a wave with a curling crest, may be indicated by the Spanish ñ.

L and Rdenote loops in which curvatures are apt to occur. L is a loop, the axis of which is straight, while R is one the axis of which is curved or crooked.

Note that if the legs of a loop widen out beyond the parallels, it is no longer a loop, but a bow or a mountain. They may narrow again and yet remain loops till at last they coalesce, when the figure is transformed into a spindle or a battledore (T, D; or K, G). If the bend is more than that of a right angle, it comes under a new definition, and has some qualities of the whorl or spiral, but is more complex. This need not be entered upon here.

S and ZI have used these two consonants to indicate certain patterns of a sinuous, undulating, or zig-zag type, the sinuous or purely undulating figures coming under S, but under Z if there is at least one distinct angularity in the pattern.

XThis letter, long familiar to the student of algebra as the symbol of the undetermined, I have reserved for the inclusion of various nondescript and anomalous patterns. Those might become fairly numerous in an extensive register, and in such case there would, no doubt, be found a good basis for fresh sub-classification.

F and HThese two aspirates are made to do useful service, not unlike that of vowels, but not of sufficient interest to be noted in a work like this.

We have thus, with the use of consonants alone, built up a kind of osseous or skeletal system, and we have now but to add the vowels to make those dry bones speak. Let us now consider this element in the syllabic method.

AThis vowel indicates that the interior of a given loop, whorl, circle, or containing pattern of any kind, is empty or vacant. Dealing here only with the simpler conditions in which combinations of vowels and consonants are found, such a figure will be indexed as Ra, La, Ta, Da, as the dominant consonant may require. Such combinations as ar, al, at, ad, etc., may occur, but this would lead us into too many intricate ramifications for a work like the present.

If a pattern is very simple – consisting, for example, of almost parallel lines – it may be denoted by the letter A alone. There are such patterns, and they seem to be somewhat commoner among certain of the negro tribes. I have mentioned in a previous chapter such a pattern on the toe of a lady, and they are typical almost in some monkeys.

EWhen we find in the interior of some loop, bow, or other pattern, a group of not less than three short detached lines, or dots, this is to be indicated by the use of E with the ruling consonant, as te, re, me, and so on.

Istands for a simple detached line, or not more than two parallel lines, in the heart of an encircling pattern.

Ostands for a little oval or circle, or for a round or oval-shaped dot in a core. If the circle, oval, etc. is large, extending over a width occupied by two lineations, then it is treated as a consonantal form. [See also Q.]

Uindicates a fork with two or more prongs within a core, forking towards the bend of bow, loop, mountain, etc. A single prong or spur standing out like a twig is to be distinguished from a fork.

Yis for a similar fork as described above, but turning its two or more prongs away from the concavity of its enclosing loop, bow, etc.

Besides the direct combination of simple vowels and consonants, which arrangement by itself gives great variety to the index registers, an immense number of syllables are formed by combinations of two or more consonants, while some few of the vowels are treated as long or short where the pattern needs further discrimination; as, for example: —

bra, spo, art, prīd, prĭd, nut, nūt.

By this method the most extensive register is gripped and needs no other index than its own essential structure. If the sheets or cards are kept in their proper sequence, and it would require to be the duty of some one – not necessarily an expert – to see that the alphabetic syllables were kept in serial order, there should be no difficulty in finding the document sought for, if it is there at all.

In translating fresh finger-prints into syllabic form, one has to catch the ideal design, so to speak, in the pattern. The consonantal skeleton, in one of its duplicate forms, is then examined for its containing vowel, and the syllable is complete. The work can be done with amazing rapidity after one is familiar with the patterns, which soon appeal direct to the eye as the type does in a printed book.

Let us now look at a few examples tabulated to show how the system works in detail.

Vowels and Consonants in Syllabic Classification with typical specimens of figure elements.

CHAPTER VIII

PRACTICAL RESULTS AND FUTURE PROSPECTS OF DACTYLOGRAPHY

Till quite recently the method of identifying prisoners was that of personal recognition, often very admirably carried out. One may readily conceive that a criminal officer, a Bow Street runner of the old school, or a modern detective, might acquire great acuteness in perceiving points of individual character in face, form, gait, speech, and manner; and during the period of arrest, trial, and imprisonment there were many opportunities of observing notable offenders. Nor is such a power to be despised at the present time. How helpful a little point might even be under skilful disguise occurred to my own mind in this way. When I saw the great Henry Irving in the part of Mephistopheles in “Faust,” a certain slight stiffness in the calves was assumed, by me, to be a very clever and subtle suggestion of the cloven hoofs which were supposed to aid the movements of that mediaeval personage. But the great actor walked other totally different parts in the same way, so that on the street, in any disguise, the notice of an acute detective might have been arrested. I am shortsighted, but can often recognize people at a distance too great to distinguish features, by some peculiarity of gait or gesture. In Taylor’s Manual of Medical Jurisprudence [ed. of 1891, pp. 317, 318], there is a curious and interesting example of how recognition sometimes failed. The story is thus told: —

“A trial took place at the Old Bailey in 1834, in which a man was wrongly charged with being a convict, and with having unlawfully returned from transportation. The chief clerk of Bow Street produced a certificate, dated in 1817, of the conviction of a person, alleged to be the prisoner, under the name of Stuart. The governor of the gaol in which Stuart was confined believed the prisoner to be the person who was then in his custody. The guard of the hulks to which Stuart was consigned from the gaol swore most positively that the prisoner was the man. On the cross-examination of this witness, he admitted that the prisoner Stuart, who was in his custody in 1817, had a wen on his left hand; and so well-marked was this that it formed part of his description in the books of the convict-hulk. The prisoner said his name was Stipler: he denied that he was the person named Stuart, but from the lapse of years he was unable to bring forward any evidence. The Recorder was proceeding to charge the jury, when the counsel for the defence requested to be permitted to put a question to an eminent surgeon, Carpue, who happened, accidentally, to be present in court. He deposed that it was impossible to remove such a wen as had been described, without leaving a mark or cicatrix. Both hands of the prisoner were examined, but no wen, nor any mark of a wen having been removed, was found. Upon this the jury acquitted the prisoner.”

Charles Dickens, aided by the pencil of “Phiz,” in The Pickwick Papers, gives us the power of seeing the process of “portrait taking,” which was simply done by a group of runners and warders staring hard at the prisoner and noting his points.

In a Blue Book, Identification of Habitual Criminals, published in 1892, which contains the report of a Committee appointed by Mr. Asquith, who was then Home Secretary, we read that: —

“The practice of the English police, though the details differ widely in different forces, is always dependent on personal recognition by police or prison officers. This is the means by which identity is proved in criminal courts; and, though its scope is extended by photography, and it is in some cases aided by such devices as the registers of distinctive marks, it also remains universally the basis of the methods by which identity is discovered.”

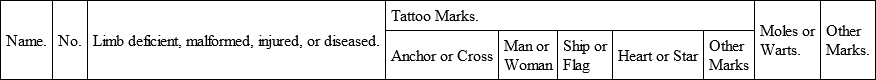

The Register of Distinctive Marks, such as the wen in the case just mentioned, contained under nine divisions of the body those permanent scars from wounds, operations or burns, tattoo marks, moles, wens, warts, mother marks, etc., which might be expected to prove helpful in identification. Those registers were published annually, and distributed to all the different forces throughout the country. The system does not seem to have been very successful. For example, out of sixty-one enquiries, in twenty cases no information was obtained. As to the remaining forty-one cases, eight were incorrect, while of ten cases no ultimate intelligence reached the Registrar. The conclusion of the Committee is thus stated (p. 8): —

“It appears to us, therefore, that the comparative failure of these registers is due, not to any want of care in the way in which the work has been done, nor to the mode of classification, but rather to the inherent difficulty of devising any exhaustive classification of criminals on the basis of bodily marks alone, and also to the difficulty of using a register of criminals that is published at intervals and in a printed form.”

Four years before this, as I have stated, I submitted to Inspector Tunbridge, deputed from Scotland Yard to meet me, an “exhaustive classification of criminals on the basis of bodily marks alone,” but the chairman of that Committee, now Sir Charles E. Troup, told me himself, at the Home Office, that he had never heard anything of it. It is now, however, in use pretty well throughout the civilized world.

Some progress, nevertheless, was made. A card index was recommended, and greater definiteness in the description of the bodily marks was to be observed. A very notable change was also foreshadowed in the whole conception of the subject.

It is interesting now to read that “it was strongly represented to us by Chief-Inspector Neame and his officers, that there should be greater precision in the taking of descriptive marks, and that their distance from fixed points in the body should be measured and recorded.” Science is measurement, and it is highly creditable to the English police that this demand was now to come from them.

Here is a specimen of the Register Form as applying to the Right Arm – one of the nine divisions of the body for this purpose.

A “scar on the forehead” was so common a mark of the criminal class, that, unlike the brand of Cain, it had no distinguishing value. One curious point, which has surely escaped the notice of writers of detective stories, was that in Liverpool “special registers are kept of the maiden names of the wives and mothers of criminals, as it is found that in a large proportion of cases an offender, when he changes his name, takes either his wife’s or his mother’s.” It is curious that, in France, a criminal more readily gives his own name correctly than in this country, but the trustworthiness of the finger-print records is now slowly working to a similar frame of mind among English recidivists. Photographs had been taken, as they are now to some extent, and they are, indeed, often most useful. Certain “routes” were arranged, and the forms and photographs were sent round the circuit of police stations, so as to be returned within the usual week of remand. Remarks on these forms were not used as evidence, but were used for official guidance only. The word “photograph” seems now (1912) to comprehend the taking of finger-prints in the official method with ordinary printer’s ink.

With all the precautions then available, it was found that mistakes in identification involved unjust suffering. A man named Coyle was sentenced for larceny in 1889, a Millbank warder swearing to his previous conviction, ten years before, as one Hart. The jury having examined Hart’s photograph gave a hostile verdict, the distinctive marks of the two men were found to be different, and Coyle moreover showed that he had been doing a short term when Hart was in prison. As is wisely stated in p. 23 of the Report: “The true test of the efficiency of a system of identification is not the number of identifications made, but the number of mis-identifications, or of failure to identify.”

A woman lacking her left breast was identified with another who had suffered in the same way, and who had been previously convicted. It became clear that the women were different, and poor Eliza – had her punishment accordingly reduced from seven years’ penal servitude to six months’ imprisonment.

A case in 1908 was that of two men charged with burglary, both of whom were short of a fore-finger, and were about the same age and of similar appearance.