полная версия

полная версияDactylography

Henry Faulds

Dactylography / Or The Study of Finger-prints

Dactylography, frontispiece

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION: EARLY HINTS AND RECENT PROGRESS

Dactylography deals with what is of scientific interest and practical value in regard to the lineations in the skin on the fingers and toes, or rather on the hands and feet of men, monkeys, and allied tribes, which lineations form patterns of great variety and persistence. The Greeks used the term δάκτυλος του̑ ποδός (daktylos tou podos, finger of the foot) for a toe; and the toes are of almost as much interest to the dactylographer as the fingers, and present similar patterns for study.

In primitive times the savage hunter had to use all his wits sharply in the examination of foot and toe marks, whether of the game he pursued or the human foe he guarded against, and he learned to deduce many a curious lesson with Sherlock Holmes-like acuteness and precision. The recency, the rate of motion, the length of stride, the degree of fatigue, the number, and kinds and conditions of men or beasts that had impressed their traces on the soil, all could be read by him with ease and promptness. Such imprints have been preserved in early Mexican picture writings.

Footprints in Ancient Mexican Remains.

Inset: Threshold with Foot-Marks (also Mexican).

In a similar way the palæontologist strives to interpret the impress made by organisms on primeval mud flats or sandy shores æons ago. There are numbers, whole species indeed, of extinct jelly fishes the existence of which has never been known directly, but that there once were such beings in the world has been confidently deduced from the permanent impressions their soft and perishable bodies have left in the fine texture of certain rocks. The Chinese tell us that one of their sages first learned to write and to teach the use of written characters by observing the marks made by a bird’s claws.

When we approach the limits of written history we begin to hear faint inarticulate murmurs of a time when the lines on human fingers began to arrest notice and interest. Thus we sometimes find in later neolithic pottery, nail and finger marks, used to adorn the sun-dried pots in common use. The Babylonians used their finger nails as seal-marks on commercial tablets, and the Chinese have occasionally done the same. Not many years ago, as I myself have often witnessed, when sealing-wax or wafers were used more than they are now, servant girls were wont to impress their thumb-mark on the soft wafer or wax. There are several characters in the Chinese alphabet (of some 30,000 letters) which suggest such a use of finger-marks as seals, but after many years’ enquiry, I have not yet seen any direct evidence of their use for such a purpose.[A] The term Sho-seki is used in Japanese to denote foot-prints, and also the tracking of anyone. I have not met any passage or expression in which finger-prints are mentioned in Japanese works, except in regard to fantastical images of footprints of Buddha and the like. It is claimed, however, that prisoners on conviction were required to adhibit their mark as a seal of confession.[B] There has been no evidence adduced that either in China or Japan was there ever a system of identification by that means, although it is conceivable that the form of making a sign-manual may have originated from some dim perception of their value for identification.

In a similar way finger-marks were used, as I have been informed, in India, even before the mutiny, and were supposed to be used like the cross made by illiterate people in this country. The numerals up to five seem to have been obtained by marking off fingers. A dactylic origin of V as an open hand, complete with outstretched thumb, has been favoured. X (ten) might easily then be obtained by placing two V ’s apex to apex.

There are certain folds or creases in palms and soles, which are formed very much as the creases in gloves or boots are formed, and with those the dactylographer is not much concerned. Such lines were supposed by many to mark the fateful influence of stars on the destiny of their owner, and are the basis of palmistry. Similar lines are found in apes. There are general patterns of lineations all over the palmar surface of the hands and the plantar surface of the feet which are of some interest, but the chief practical concern of most students in this new field is with certain points where patterns run into forms of great complexity, especially in the palmar skin covering the last joint of each finger. It is not common to find either in pots or pictures those patterns printed clearly, but the creases dear to the palmister are frequently enough shown.

In Mr. C. Ainsworth Mitchell’s Science and the Criminal, published in 1911, a case is mentioned of a very early finger-print, if the evidence has not been fallacious: —

“In the prehistoric flint-holes at Brandon, in Suffolk, there was found some years ago a pick made from the horn of an extinct elk. This had been used by some flint-digger of the Stone Age to hew out of the chalk the rough flints which were subsequently made into scrapers and arrow-heads. Upon the dark handle of this instrument were the finger-prints in chalk of the workman, who, thousands of years ago, flung it down for the last time.”

It is now in the British Museum. A foot-print also has been found of very early date.

Such white marks on a dark ground are often very clear, showing the detail of lineations well, and presuming, as is natural, that the ordinary precautions were taken to secure that they were not recent accidental additions to the remains, such a record is highly valuable.

It was apparently a common practice in ancient India to adorn buildings with crude finger-marks made with white or red sandal-wood. The red hand common on door-posts and the like in Arabia does not usually show any lineations, but in some few ancient and primitive carvings and in sun-baked pot-work, patterns occur which appear to me to have probably had finger-print lineations as a motif. Professor Sollas, in writing of Palæolithic Races in Science Progress (April, 1909) – a subject of which he is a master – says: “Impressions of the human hand are met with painted in red in Altamira, but in other caves also in black, and sometimes uncoloured on a coloured ground. These seem to be older than any of the other markings.” Some cases are stencilled, as with Australians to-day.

The same writer, in a foot-note, also states, in describing caves and paintings of modern Bushmen: “Impressions of the human hand are also met with on the walls of these caves.”

A traveller, Mr. John Bradbury, who witnessed the return of a war-party of the Aricara Indians, says: —

“Many of them had the mark which indicates that they had drank the blood of an enemy. This mark is made by rubbing the hand all over with vermilion, and by laying it on the mouth it leaves a complete impression on the face, which is designed to resemble and indicate a bloody hand.” – [Travels in the Interior of America (1817).]

The ancient bloody hand of Ulster is well known, and other examples occur which might be quoted.

Some “prehistoric pottery” was found last autumn at Avebury, North Wilts, of which I have not seen full particulars. In a press paragraph, however, it is stated that its chief interest “centres in the fact that it is ornamented on both faces – the impressions of twisted grass (or cord) and finger-nails being clearly defined.” It is temporarily classified as a type of pottery associated with long barrows and neolithic pits.

My own attention was first directed to the patterns in finger-prints, as they occurred impressed on sun-baked pottery which I found in the numerous shell-heaps dotted around the great Bay of Yedo. The subject was quite unknown to me till then, in the seventies. No pottery has yet been found which belongs to the early stone stage of man’s culture. But with evidence of the use of fire, and of the manufacture of polished stone weapons, fragments of rude hand-moulded pottery – sun-baked or fire-burned – begin to be associated. Sometimes these are quite clearly seen to be moulded with the aid of human fingers, the nails only making a clear mark, but in other cases the finger furrows are prominently indented in regular patterns, which cannot, I think, be distinguished from those made by men of our own race and time. In the formal Japanese ceremony of social tea-drinking, or Cha-no-yu, pottery of this Archaic kind, with finger patterns indented in the clay, is highly esteemed. In an article on this kind of pottery by Mr. Charles Holme, in The Studio (February, 1909), one example is described thus: “It is modelled in a brown clay entirely by hand, without the aid of a potter’s wheel. The impressions of the fingers made in shaping the bowl are carefully retained,” etc. Not till Celtic times in Europe is there evidence of the use of the potter’s wheel.

I am surprised to find how very little attention has yet been given to finger imprints on early pottery. My own opportunities for observation have in late years been severely limited, but I have seldom had a peep at ancient potsherds without discovering some few traces of the kind of impressions, accidental or designed, which I have described. I have not had early Teutonic pottery specially under observation, but Professor G. Baldwin Brown, who is an accomplished authority in that department, wrote me thus: —

“In the early Teutonic pottery, so far as I have examined it, the ornamental patterns are produced by drawing lines and furrows with some hard tool, such as a shaped point of wood or bone. It is very rarely that the furrows or circular depressions have the soft edges which would suggest the use of the finger, and I have never noticed the texture of the finger-tip impressed on the clay, though I have not looked specially for this with a glass. Ornaments are also commonly impressed with a wooden stamp on which some simple pattern has been cut. The only ornamental motive which seems to spring directly out of manipulation by the fingers is the projecting boss, characteristic of a certain class of Teutonic ware. The clay is forced out from within in the form of a knob or a flute, and the idea of such an ornamental treatment has probably arisen from the accidental projections produced in the exterior surface of the vase by the pressure of the fingers when the vase is being shaped from within. There is nothing in early Teutonic pottery like the coiled Pueblo pots, or other products where the pressure of the fingers on the exterior has generated the whole ornamental scheme.”

Antique references to finger-print patterns are not numerous. In the anatomical text-books of my student days, I cannot recall a single example of their having been noticed or figured, and no figure was printed in the usual plates of anatomy of my time. Malpighi, writing in 1686, tersely alludes to the ridges which, he says, form different patterns (diversas figuras describunt).

Both Sir William Herschel and myself have publicly called for evidence of the alleged use in the Far East of finger-prints being used for identification. During my residence in Japan I was intimate with the leading antiquarians, and was repeatedly assured that nothing was known by them of any such legal process. Mr. T. W. Rhys Davids, Secretary of the Royal Asiatic Society, of which I was formerly a member, wrote me in answer to an inquiry as to this point, on the 17th May, 1905: —

“Dear Sir, – I have heard of thumb marks being used in the East as sign-manuals, but I know no single case of thumb or finger marks being used for identification, and, pending further information, I do not believe they ever were so used in ancient times in any part of the East.”

Every now and again I receive letters telling me of some one who thinks he remembers some one saying that he saw, etc., etc. Now, surely, it would not be difficult if anyone were to find such evidence, to send a copy or photograph duly authenticated, and a date attested subsequent to the date of publication by Nature, in 1880, of the correspondence on this subject. A good deal has been written about Professor J. E. Purkenje (or Purkinje) in this connection. One enthusiastic fellow-countryman has mentioned with eulogy a purely imaginary course of lectures on Identification by Finger-Prints. Purkinje does not seem ever to have dreamed of putting them to such a use. In The Daily News of January 23rd, 1911, an interview is reported with Sir Edward Henry, who is made to state that Purkinje “wrote about the value of finger-prints for purposes of identification”; but on enquiry Sir Edward assured me he had not said anything beyond what was stated in his work on Finger-Prints, and in that work, of course, no such statement is hinted at as that Purkinje proposed to secure identification by finger-prints.

As a student I was fairly well acquainted with much of what that keen observer had written, and when I was lecturing to medical students in Japan on the Testimony of the Senses, I could not help noticing that while Purkinje had been busy with the fingers and with the special development in their sensitive tips of the organs of touch, no records had been preserved which mentioned his notice of the finger-furrows or the patterns made by them. I took much trouble in the matter, writing to eminent authorities and to librarians, and found no trace of any such work. Sir F. Galton, in his published writings, is quite in accord with me so far, but he has not explained how he came to think of Purkinje’s work. Writing in 1892 on Finger-Prints, (p. 85) he says of the subsequent discovery of a thesis of 58 pages: “No copy of the pamphlet existed in any public medical library in England, nor in any private one, so far as I could learn; neither could I get a sight of it at some important Continental libraries. One copy was known of it in America.” The American copy was not known generally till I had made vigorous enquiries there. Sir F. Galton adds, “The very zealous librarian of the Royal College of Surgeons was so good as to take much pains at my instance to procure one: his zeal was happily and unexpectedly rewarded by success, and the copy is now securely lodged in the library of the college.”

As Sir Francis began to give attention to this subject in 1888 (p. 2 of work just quoted) it is only justice to myself in the matter to state that in June, 1886, I called on the then librarian of the Royal College and impressed upon him my conviction that as nothing had then been known of any printed work by Purkinje on this topic, a search among his remaining papers should be made, as to me it seemed improbable that, working so closely in that field, Purkinje could fail to observe the patterns of the finger-furrows. It seemed as certain a deduction to me as was that of the existence of Neptune before that planet had been actually discovered. The pamphlet is in Latin, a work of 58 pages, printed at Vratislav, (i.e., Breslau) in 1823. In the article on “Finger-Prints,” in the Encyclopædia Britannica (1911) it is stated that “the permanent character of the finger-print was put forward scientifically in 1823 by J. E. Purkinje, an eminent professor of physiology, who read a paper before the university of Breslau,” etc. But he was surely not a professor when graduating, and what passage in that thesis, may I ask, deals scientifically with the permanent character of the finger-print? Purkinje had studied the lineations of monkeys as well as those of men.

In Tristram Shandy (1765) we read of “the marks of a snuffy finger and thumb.”

Jack Shepherd, a novel of Ainsworth’s, was published in 1839. One Van Galgebrook, a Dutch conjuror, therein foretells Jack’s bad end: “From a black mole under the child’s right ear, shaped like a coffin … and a deep line just above the middle of the left thumb, meeting round about in the form of a noose.” It would be interesting to know how Ainsworth happened upon the suggestion.

Single Finger-Print

Bewick sometimes jestingly left his sign-mark on his fine wood-engravings, and those thus attested by his thumb-print are now specially valued.

Many references occur in modern literature to fingerprints, and in David Copperfield, published in complete form in 1850, Charles Dickens tells how Dan’l Peggotty, in the old boat-house at Yarmouth, “printed off fishy impressions of his thumb on all the cards he found.”

Pater, in 1871, writing of the Poetry of Michelangelo, mentions “the little seal of red wax which the stranger entering Bologna must carry on the thumb of his right hand.”

Later references are very common after the eighties. Alix in 1867–8 wrote on the papillary lines of hand and foot in Zoologie, vols. viii. and ix., contributions which were first brought to my notice after the publication of my Guide.

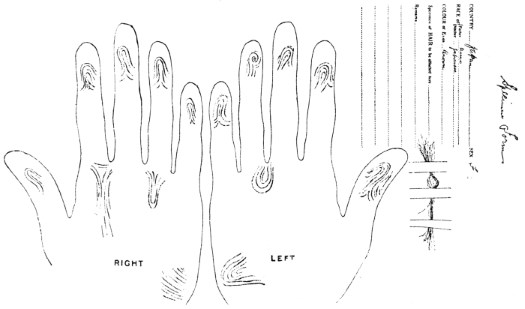

Facsimile (reduced) of the Original Outline Forms for Both Hands.

Done in copperplate for the author in Japan at close of 1879 or in January, 1880. The lineations were filled in with pencil at the same period.

In 1879 I engaged a Japanese engraver in Tokyo to make for me copperplate forms in which to receive impressions of the fingers of both hands in their consecutive or serial order. There were spaces for information to be recorded which might be useful in anthropology, and a place to which a lock of hair of the subject was to be attached. The original proof sheet, marked by me in red pencil where special points in the rugæ were to be carefully printed, is now in the library of The Royal Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons in Glasgow, along with a letter to me from Charles Darwin on the subject of finger-prints. The figures are from reduced photographs of those two original copperplate forms, which have never before been published except as accompanying the circular mentioned below. Many of those forms were sent to travellers and residents in foreign countries, with a written circular, as follows: —

“January, 1880.“As novel and valuable ethnological results are expected from this enquiry, I trust this may form a sufficient excuse for asking you to take so much trouble. Please return any forms which may be filled up to the above address.

“Dear Sir,

“I am at present engaged in a comparative study of the rugæ, or skin-furrows, of the hands of different races, and would esteem it as a great favour if you should obtain for me nature-prints from the palmar surface of the fingers of any of the ......... race in your vicinity, in accordance with the enclosed forms. The points of special interest are marked [with red crosses] and no others need specially be attended to. Each point must be printed by itself separately. Printer’s ink put on very thinly and evenly, so as not to obliterate the furrows of the skin, is best. It can easily be removed by benzine or turpentine. In place of that, burnt cork mixed with very little oil will do very well. One or two trials had better be made before printing on the forms. If printing should be found too difficult, sketches of leading lines – at the points indicated – would still be of very great value, taking care that the directions corresponded with the furrows, and not in reverse, as when a simple impression is taken. If any one finger, and so on, comes out badly, a piece of paper can be printed and pasted on at the proper place. I enclose as a specimen a filled-up form. [The fingers printed in the proper spaces and the important ‘points’ each marked with a cross in red pencil.]

“I am, etc.,“Henry Faulds.”Many of these circulars were posted with great care to recent addresses, but the response was quite disappointing. No useful prints were obtained, and most recipients took no notice whatever of the request. I have since thought the question may have been confused with palmistry. It was not easy to get impressions from the paws of monkeys, apes, and lemuroids in Japan. Some few that were obtained at once betrayed a very strong similarity to those of man, and it seemed that a wider study would yield some hints, perchance, as to the path of man’s ascent.

On the 15th February of the same year (1880), I wrote to the great pioneer in this field, Charles Darwin, sending specimens of prints and some outline of my first tentative results, and requesting him to aid me in obtaining access to imprints from lemurs, lemuroids, monkeys and anthropoid apes, as I had found them to show lineation patterns which I hoped might be serviceable to elucidate in some degree the lineage of man. I had failed to find any trace of references to these phenomena in any anatomical or biological work within reach. The few Oriental works I had seen were full of absurd phantasies and were allied to palmistry, but contained Buddhist and Taouist figures nowhere to be found in nature.

The great naturalist’s reply, in his own handwriting, sent to me two years before his death, was as follows: —

Via Brindisi

April 7th, 1880.

Down,Beckenham, Kent,Railway Station,Orpington, S.E.R.“Dear Sir,

“The subject to which you refer in your letter of February 15th seems to me a curious one, which may turn out interesting; but I am sorry to say that I am most unfortunately situated for offering you any assistance. I live in the country, and from weak health seldom see anyone. I will, however, forward your letter to Mr. F. Galton, who is the most likely man that I can think of to take up the subject to make further enquiries.

“Wishing you success,“I remain, dear Sir,“Yours faithfully,“(Signed) Charles Darwin.”This letter, with the envelope addressed by Mr. Darwin himself, and showing its postmarks, is in the library of the Royal Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons. Mr. F. Galton, afterwards Sir Francis Galton, a cousin of Charles Darwin, wrote in Finger-Prints, which was published by him in 1892, that his “attention was first drawn to the ridges in 1888 when preparing a lecture on Personal Identification for the Royal Institution, which had for its principal object an account of the anthropometric method of Bertillon, then newly introduced into the prison administration of France.” [p. 2.]

In Nature, October 28th, 1880, appeared my article which was indexed shortly afterwards as the first contribution on the subject, in the Index Medicus of the United States, thus: “Faulds, H. – On the skin-furrows of the hand, Nature, London, xxii, 605.”

Professor Otto Schlaginhaufen, while my Guide was going through the press in England, published in the August number of Gegenbaur’s Jahrbüch for 1905 a copiously illustrated and well-informed article on the lineations in human beings, lemuroids, apes and anthropoids. The writer does me the honour of stating (p. 584) that with my contribution to Nature in 1880, there begins a new period in the investigation of the lineations of the skin, that, namely, in which they were brought into the service of criminal anthropology and medical jurisprudence. This publication, he says, is the forerunner of a copious literature which flowed over into the popular magazines and daily press, and promises to keep no bounds. He thinks that I pointed the right way to attain a knowledge of man’s genetic descent by a study of the corresponding lineations of certain lower animals, such as lemuroids, and that I had suggested other directions in which medical jurisprudence might profitably engage in the study of this subject. A claim was shortly afterwards made in Nature, by Sir William Herschel, that he had, prior to my efforts, taken finger-prints for identification in India. I have entered into this personal matter elsewhere. Sir William has more than once publicly conceded priority of publication to me, and that is not at all disputable. We quite independently reached similar conclusions. Schlaginhaufen sums up the matter at least impartially, thus: —