полная версия

полная версияDactylography

In a few cases, especially in the feet patterns, often a very plain character, parallel or slightly wavy lines of no precise design, so to speak, may be found. A short time ago, when applying mustard to the feet of a lady in some kind of fit, I observed this almost featureless pattern in her toes. If such cases were as common in the hands as they are rare, the finger-print method would hardly be of any avail for identification. A teleologist of the old school of Paley might argue with some plausibility that the possible usefulness of those intricate patterns was the true meaning of their existence, otherwise not yet explainable. That the old Paleyan conception of nature having an end or purpose in view, the teleological explanation of things as useful to the being possessing them, had its own usefulness in giving a broader view of natural history facts in their interrelations, is borne out even by so great an authority as Charles Darwin himself. Are the markings in a bird’s eggs recognized by the sitting bird in those cases where the markings are peculiar – and some are like written characters – or are they purely accidental and useless? A correspondent in The Country-Side wrote a short time ago, describing a test case he observed of a thrush in his possession. This bird built a nest and laid therein five eggs, “varying in size from a good-sized pea to the normal size. The smaller ones I took away and substituted one from a wild bird’s nest; this the following day I found laid at the bottom of the aviary smashed. I again repeated the addition with the same result. I had carefully marked the eggs, so that there could be no mistake.” The writer signed himself “W. A., Wimbledon.”

Dr. Wallace’s view, as I understand it, is that variations in wild animals were due chiefly to immunity from enemies, allowing free play to the natural tendency to variation, kept only in check by its dangers, such as leading to betrayal by conspicuous colouring, and so on. Professor Poulton in The Colours of Animals, 2nd ed. p. 212, says: —

“It is very probable that the great variation in the colours and markings of birds’ eggs, which are laid close together in immense numbers, may possess this significance, enabling each bird to know its own eggs. I owe this suggestive interpretation to my friend, Mr. Francis Gotch: it is greatly to be hoped that experimental confirmation may be forthcoming. The suggestion could be easily tested by altering the position of the eggs and modifying their appearance by painting. Mr. Gotch’s hypothesis was formed after seeing a large number of eggs of the guillemot in their natural surroundings.”

Australian ewes know the bleat of their own lambs, however immense the flock, and all through nature we find this useful note of recognition. One of the most philosophic interpreters of living phenomena, viewing things from a very recent standpoint – Professor J. Arthur Thomson, in his fascinating Biology of the Seasons (p. 174), writing of the colour and texture of birds’ eggs, says: —

“In some cases, it is said, the shell registers hybridism – a very remarkable fact. It is another illustration of the great, though still vague, truth that the living creature is a unity through and through, specific even in the structure of the egg-shell within which it is developed. For although the shell is secreted by the walls of the oviduct, it seems to be in some measure controlled by the life of the giant-cell – the ovum – within.”

Such pattern-forming qualities are found in many fields of nature, very beautifully, for example, as we have seen, in the skin of the zebra; on the back of a mackerel; in the grain of various kinds of wood; in the veining of leaves and petals; and in the covering or substance of seeds such as the nutmeg and scarlet runner bean. Sir Charles Lyell, in his Elements of Geology, figures the ribbing of sand on the sea-shore in a wood-cut which might be an enlarged diagram of human skin. (See fig. on page 32). In his Principles of Geology (5th ed., vol. i., p. 323) there is, again, a figure described as a section of “spheroidal concretionary Travertine,” which contains many linings strikingly like those with which we have to deal in this little work.

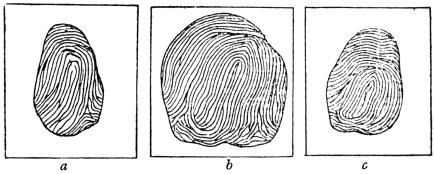

a. section of pine-wood stem.

b. a human thumb-print.

It follows from these analogies that a method of analysing and classifying such patterns might have very wide utilities beyond its relation to finger-prints. It is easy, for example, to recognize the same zebra in quite different pictures. Another point of practical importance is this, that a smudgy or blotchy impression, supposed to be that of a criminal present at some seat of crime, might be the impressed copy merely of some object or texture other than human skin, but containing lineations of similar arrangement. An outworn transversely cut branch of a tree might readily produce a print like that of a human finger. An expert would probably notice that in the lineations there were no real junctions, each woody ring remaining apart from the others; but, again, there are some human fingers of such patterns. I think the bloody smear officially reproduced as impressed on a post-card in facsimile, and purporting to have come from “Jack the Ripper,” at the time of the Whitechapel horrors in the eighties, may have been produced by the sleeve of a twilled coat smeared with blood. It contained no characters specially characteristic of skin lineations, which it was presumed to be an example of, as impressed.

Apart from all that, lemurs, lemuroids, apes, anthropoids, and monkeys, all show on hands and feet, skin lineations in patterns similar to those of man. In the anthropoid apes it would not be easy to discriminate them from those of human beings. Some of these were figured in my Guide, and Dr. Otto Schlaginhaufen has supplied numerous good prints.

If Edgar A. Poe, in his famous mystery of evil deeds done by a gigantic ape, had been acquainted with finger-print methods, he might have pictured the police as still more mystified by the imprints of seemingly human hands.

There are two methods of observing systematically the lineation patterns.

1. —The Direct Mode.– This might be done simply by many people by looking at the lineations with the unaided vision. Till quite recently the author found no difficulty in doing this, with myopic eyes that could see something of the texture of a house-fly’s eyes in a good light. My earliest observations of the finger-patterns were made in this way, while the patterns were reproduced in pencilled outlines. The condition of the actual ridges and furrows themselves, with their open and acting or closed and dormant sweat-pores, ought to be familiar to the student of dactylography, who is apt to narrow his vision by the contemplation only of dead impressions made in ink or otherwise. A lens such as botanists use for field work is very useful, and a high power is neither necessary nor very helpful. Drawings of the patterns ought to be made from time to time with coloured or “lead” pencils, and those drawings should be accurately adjusted by the use of rubber and compasses.

2. —The Indirect Method.– This is done by the medium of casts and printed impressions. Casts may be made of clay, putty, sealing-wax, beeswax, gutta-percha, hard paraffin, varnish, half-dry paint, and the like. Printed impressions or dactylographs may be obtained from greasy or sweaty fingers, blood, printer’s ink, or various substitutes for it.

Within this method, again, two very distinct and complementary kinds of results may be obtained, which I have elsewhere described as Positive and Negative. The first or Positive is that, for example, which is used officially for the record of convicted prisoners by printing with ordinary printer’s ink, just as a veined leaf or fern, or a box-wood engraving is printed from. Here the ridges or raised lines appear black on a white ground, while the intervening furrows appear white, as do also the minute pores dotted along the crest of each ridge. (See frontispiece.)

In the other method, as when the fingers are impressed on a carefully smoked surface of glass, the projecting ridges lift up the carbon of the soot, leaving a white pattern behind, with the sweat-pores forming black punctuations, while the receding furrows leave the black surface untouched. When such impressions have to be used again, as for evidence, they should be carefully varnished, as they are exceedingly liable to be destroyed by the slightest contact.

In a case under judicial investigation where an official imprint had to be compared with one done by accident negatively on smoked glass or the like, the black lineations would not closely correspond – would, in fact, considerably diverge in pattern. This might tend to confuse judge and jury if the distinction of negative and positive dactylograph were not made clear by the expert witness. Then the apparent divergences could easily be demonstrated to be very significant coincidences.

Five years of my early life were spent in learning a trade in Glasgow – that of the soon-to-be-obsolete Paisley shawl manufacture. It seemed to me to have been an utter waste of time, but part of my duty was to deal with the arrangement, classifying, and numbering immense varieties of patterns, printed with every conceivable variation of combined colours. It was impossible to carry these on memory, and one had to resort to mnemonic means of classification.

Now, the immense significance of the variety in human finger-patterns dawned upon me very early, when I had once begun to interest myself in them.

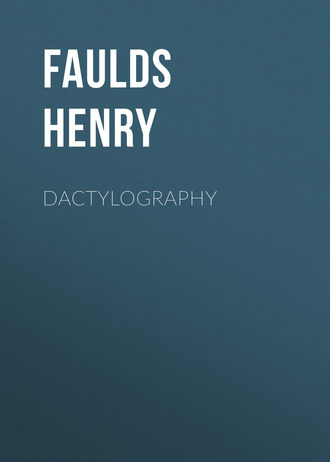

Design-like Patterns in Finger-Prints No. 1.

(Diagrammatic)

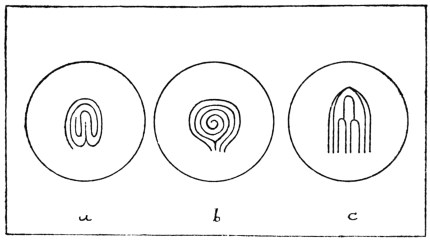

Design-like Patterns No. 2.

There are many patterns, which, when analysed into their composing elements, present analogies to artistic designs, a view which is no mere personal fad, but has been affirmed with enthusiasm by many artists in designs to whom I have pointed out those figures. Here are a few, by way of illustrating this point (space will not permit of more). Those figures are from real human finger-prints rendered diagrammatically. This is the first step, then, to catch with the eye the pattern or design; give it a class name, and you have at once established some practical basis of classification in finger-prints. Then it is possible to frame some kind of catalogue for reference arranged like a dictionary with its sub-alphabetic order, in an almost infinite series. The initial difficulty is generally that which arises from want of skill in printing, which technical points will be considered subsequently. A soft and flexible substance like the ridges in human fingers does not always yield an exactly similar impression in two successive moments, under varying conditions of temperature, fatigue, and the like. Nor does the analogy of mathematical diagrams always fitly apply in such a case. Even in steel engravings and fine etchings, as the connoisseur well knows, the degree of intensity of the pressure and other conditions will modify to some slight extent the resulting imprint, but what I wish to emphasize is, that if the original pattern had any value at all resulting from its complexity as a pattern, the variation in printing as now done officially by experienced police officials will not impair much its value as evidence of personal identity in a court of law. Even the amateur will soon, after a little practice with good materials, attain a very fair amount of clearness and uniformity in his imprints.

CHAPTER IV

SOME BIOLOGICAL QUESTIONS IN DACTYLOGRAPHY

In this chapter I propose to bring together a few important points of a biological character, which are so vital that even in so curtailed a discussion they cannot be ignored. We shall also glance – it must literally be the merest glance – at the problem of man’s genetic descent, in so far as it begins now to be illumined, however faintly, by a comparative study of finger-prints. Comparatively little of a final character has as yet been achieved, but there are now not a few active and intelligent observers in many lands, and the scientific results often attained under the greatest difficulties are so far greatly encouraging. Fortunately the day has long passed away when it can be considered irreverent to enquire modestly as to who were one’s ancestors. In a very true biological sense every human individual is known to have run through a scale of existence, beginning from the lowest mono-cellular organism, through something like a tadpole or salamander, into a vertebrate and mammal type, not easily to be discriminated from the undeveloped young of rat, or pig, or monkey. Now, if he is not in any way individually degraded by this actually demonstrable course of development, why should he be thought racially degraded by an honest scientific effort to trace the origin of his species from lowly animal ancestry? The process may be slower, but is no less determined by divinely established law. Our grandfathers believed that the Creator breathed into the organized and shapely form of Adam (= “a man”) a portion of the divine spirit, by which he became a living soul, and forthwith took his dignified place in nature. To me the old story, when retold in more modern and exact phrase, leads us to an entirely hopeful and inspiring conception of the origin and evolutionary destiny of our race.

When we approach the threshold of man’s first appearance on the globe, we have reached a geologic epoch when our sober earth seems to have sown most of its wild oats. Its “crust” is pretty stable, and at least in its broad distribution of sea and land, it does not seem to differ very greatly from what its appearance presents on a modern physiographical map. Minor differences there must have been, as even our modern English coast-line shows, and there may have been other conditions than now exist to account for many of man’s early migrations, but those differences are still matters of discussion. There were, possibly, enough certain bridge-like links between lands now apart and separated by wide stretches of sea, but, as a rule, such conclusions have been deductively reached, and are not definitely established on scientific evidence.

After rising above one-celled to more complicated organisms, we reach a class of creatures in which a radiate or wheel-like form obtains, that is, radial symmetry, as in jelly-fish, star-fish, urchins, and sea-anemones.

Fishes occupy, perhaps, about the lowest level among the back-boned or vertebrate animals, and we may readily notice that some of their fins occur in symmetrically arranged pairs, while others, again, occur singly. Now with this arrangement of such appendages in pairs symmetrically arranged there begins the appearance of something definitely like what we mean by limbs. Some present-day fishes use some of their fins as legs to clamber and crawl on rocks or ashore. I remember seeing, in a Japanese tea-house by the solitary sea-shore, not far from where the great arsenal of Yokoska now hums busily, a very beautiful gurnard, blue as to its outspread wings like the sapphire gurnard. Those fins were painted like the wings of a butterfly, and it crawled about in the limited sea-water, on rocks, under cliffs, and among sea-weed, with butterfly-like legs or processes from the roots of those wing-like fins. With such a special adaptation of their fins, fishes began to conquer the land. Seals and whales, as is well known, are mammals which have been driven back again to the sea.

Thesing, in his suggestive Lectures on Biology (English translation, p. 13), says: —

“All extremities of the higher vertebrates, however widely they may differ in construction, may be traced back biogenetically to the so-called Ichthyopterygium, as we see it in the lower shark-like fishes. Unequal growth of the single skeleton parts and a considerable reduction in their numbers transformed the Ichthyopterygium into the five-fingered extremity characteristic of all vertebrates from the amphibians upwards.”

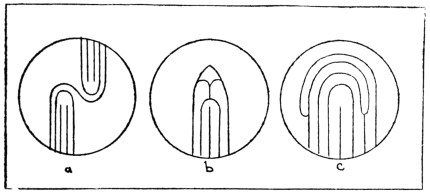

Anthropoid Lineations.

a, from hand of orang, left index;

b, from foot of chimpanzee, left index;

c, from foot of orang, left index.

Of course the great end of an animal is at first to fill its own belly, and in order to do this, if fixed as some molluscs are, it must contrive to bring nutriment within its reach, and if mobile limbs come to be developed to achieve locomotion, by fin in water, limb on land, and wing in air. After the vertebrate and mammal stage was achieved, the five-fingered limb takes various forms, as the paddle of the whale or wing of the bat. There are three great periods in geological development of animals – the Primary, which is, roughly speaking, the typical period of fishes; the Secondary, when reptiles prevail; and the Tertiary, the great age of mammals. Many geologists recognize a fourth period, the Post-Tertiary, Quaternary, or Diluvian, when existing species have been established. It is not till this latest period has arrived that we can detect unmistakable evidences of man. There are, however, many reasons which lead to the conclusion that his racial roots go still further back in time. Did he arise as a “mutation,” one of those rare sudden changes observed to take place even at the present time, by which a species suddenly departs from its ancestral type and is transformed? Let us briefly look at the main facts of mammalian ascent. The great herbivorous reptiles – some do not seem to have been strictly herbivorous – do not seem to lead us far on our path. Widely spread throughout the world, the Theriomorphs or beast-shaped reptiles seem to approach the mammal type, but they were too helpless and unwieldy, and had little brain-power wherewith to direct their energies. The earliest genuine mammals were small, not only relatively to those great creatures, but really little, rat-like rodents. Then we find arboreal creatures, driven to the trees for refuge and for food, squirrel-like animals, agile to escape from their monstrous but clumsy and stupid foes on the ground, and using their paws nimbly as hands to grasp and tear, or to break nuts and other food.

Lemur-like animals (lemuroids) then come on the stage, and among them – among the earliest of them – we begin to detect traces, on feet and hands, of those patterned ridges, the beginnings of which we have been seeking. Hand and brain and voice are the trinity of social construction. The spider and the mantis (or praying insect) have nimble, hand-like organs – very striking and conspicuous in the mantis; the chameleon among reptiles, the parrot among birds, the squirrel among lower mammals, all have somewhat hand-like organs used in hand-like ways; but when we reach the higher mammals, the sense of touch is finely intertwined with the power of varied and discriminative grasping, pressing, or rubbing. The elephant, which appears at first in the strata as about the size of a dog, grows in size and brain power as the ages roll along. But his path seems now to be closing. With his sagacious brain, and prehensile, sensitive trunk, he can do wonders, but, like the horse, he is likely to be passed by; the great tool-maker finding it easy now to make bearers swifter or more powerful than they are.

It is in man and the anthropoid apes that we first find the correspondence between hand and brain that promises mastery. The ugly, painted mandrill, even, has beautiful lady-like hands and takes care of them like a lady. All the higher apes show complicated finger-patterns like those of man.

The rugæ in apes and men seem clearly to have served a most useful purpose in aiding the firm grasp of hands or feet, a very vital point in creatures living an arboreal life, as they and their racial predecessors are now presumed to have done. In that case, however, would not one pattern, a simple one, have done as well as any other? Here, then, the great balancing principles of variation and heredity come into operation. The variety of patterns is immense, and for aught we know new ones may be being evolved at the present time. Here again, heredity comes in, for there is certainly some tendency to repeat in a quite general way the pattern of sire in the hands and feet of son. I have as yet found no quite close correspondence of detail in any case brought under my own notice. The question of identifying a person on one or two lineations involves so many practical problems of obscurity in printing and the like, that it is more appropriate for discussion in another chapter.

In a work published last year on Science and the Criminal, by Mr. C. Ainsworth Mitchell, after quoting a reference I made on one occasion to the influence of heredity in sometimes dominating finger-patterns, the author goes on to say: “While there is questionably a general tendency for a particular type of finger-prints to be inherited just as any other bodily peculiarities are liable to be passed on from the parents to the children, there is by no means that definite relationship that Dr. Faulds hoped to establish.” The full passage in my paper in Nature referred to, was this: —

“The dominancy of heredity through these infinite varieties is sometimes very striking. I have found unique patterns in a parent repeated with marvellous accuracy in his child. Negative results, however, might prove nothing in regard to parentage, a caution which it is important to make.”

The truth is, I have very frequently emphasized the fact that in such similar patterns in sire and son there is no real danger of false identification where several fingers are compared in their proper serial order. It is not even likely that two such fingers would agree exactly in lineations, number, curvature, etc., if carefully measured in the way set forth in this work.

A more remarkable criticism is to be found in p. 63, thus: “The existence of racial peculiarities in finger-prints, which Dr. Faulds believed that he had discovered in the case of the Japanese, has not been borne out by the experience of others.” The author then mentions some observations on this point by Galton, who thought that “the width of the ridges appeared to be more uniform and their direction more parallel in the finger-prints of negroes than in those of other races.” The word “negroes” here is delightfully vague in an ethnological discussion. I have written nothing to justify the above remark. My belief has long been that there is no racial difference of yellow, white, red, or black, to use the good old Egyptian classification, but that the human family is one, and that view (right or wrong) was enunciated often by me in Japan, both by speech and pen. Mr. Mitchell’s strange misconception must surely be based on my words in the article by me quoted above, where, after enumerating some elements in patterns from different races, I go on distinctly to say: “These instances are not intended to stand for typical patterns of the two peoples, but simply as illustrations of the kind of facts to be observed.”

I had pleasure in giving my subscription and support to the recent First Universal Races Congress, which has done much, I believe, to consolidate scientific opinion as to the essential unity of our kind, a belief not so old or universal as many think, dating, indeed, not much more than a century back, if so far, as a scientific opinion, not biassed by the slave interest.

Of much more importance now is the relation to human beings to the great anthropoid stocks.

It is usual to separate the lemurs, which have strong affinities to monkeys and to men, from the anthropoids, or man-like apes, forming two great orders of

Lemuroidea, and

Anthropoidea.

In 1909, however, a paper was published by the Zoological Society of London, in which this separation is considered to be no longer justifiable, so that the lemurs and big man-like apes (orang, chimpanzee, and gorilla) would no longer be held as separate orders or sub-orders. There were some who hoped to show that the races of men corresponded to three primitive anthropoid stocks, linked to the three kinds of anthropoid apes. Whether the new view be correct or not, and there is something to be said in its favour, there can be no reasonable doubt now as to the close affinity which those creatures have to ourselves and to one another.