полная версия

полная версияThe Classic Myths in English Literature and in Art (2nd ed.) (1911)

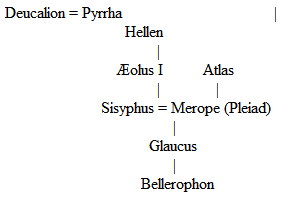

155. Textual. The descent of Bellerophon is as follows. (See also Table I.)

Lycia: in Asia Minor. The fountain Hippocrene, on the Muses' mountain, Helicon, was opened by a kick from the hoof of Pegasus. This horse belongs to the Muses, and has from time immemorial been ridden by the poets. From the story of Bellerophon being unconsciously the bearer of his own death-warrant, the expression "Bellerophontic letters" arose, to describe any species of communication which a person is made the bearer of, containing matter prejudicial to himself. Aleian field: a district in Cilicia (Asia Minor).

Interpretative. Bellerophon is either "he who appears in the clouds," or "he who slays the cloudy monster." In either sense we have another sun-myth and sun-hero. He is the son of Glaucus, who, whether he be descended from Sisyphus or from Neptune, is undoubtedly a sea-god. His horse, sprung from Medusa, the thundercloud, when she falls under the sword of the sun, is Pegasus, the rain-cloud. In his contest with the Chimæra we have a repetition of the combat of Perseus and the sea monster. Bellerophon is a heavenly knight errant who slays the powers of storm and darkness. The earth, struck by his horse's hoof, bubbles into springs (Rapp in Roscher, and Max Müller). At the end of the day, falling from heaven, this knight of the sun walks in melancholy the pale fields of the twilight.

Illustrative. Wm. Morris, Bellerophon in Argos and in Lycia (Earthly Paradise); Longfellow, Pegasus in Pound; Bowring's translation of Schiller's Pegasus in Harness. Milton (Bellerophon and Pegasus), Paradise Lost, 7, 1; Spenser, "Then whoso will with virtuous wing assay To mount to heaven, on Pegasus must ride, And with sweet Poet's verse be glorified"; also Faerie Queene, 1, 9, 21; Shakespeare, Taming of the Shrew, IV, iv; 1 Henry IV, IV, i; Henry V, III, vii; Pope, Essay on Criticism, 150; Dunciad, 3, 162; Burns, To John Taylor; Young's Night Thoughts, Vol. 2 (on Bellerophontic letters). Hippocrene: Keats, To a Nightingale.

In Art. Bellerophon and Pegasus, vase picture (Monuments inédits, etc., Rome and Paris, 1839-1874); ancient relief, Fig. 122, in text.

156-162. For genealogy of Hercules, see Table J. Rhadamanthus: brother of Minos. (See Index.) Thespiæ and Orchomenos: towns of Bœotia. Nemea: in Argolis, near Mycenæ. Stymphalian lake: in Arcadia.

Pillars of Hercules. The chosen device of Charles V of Germany represented the Pillars of Hercules entwined by a scroll that bore his motto, "Plus Ultra" (still farther). This device, imprinted upon the German dollar, has been adopted as the sign of the American dollar ($). Dollar, by the way, means coin of the valley, – German Thal. The silver of the first dollars came from Joachimsthal in Bohemia, about 1518. Hesperides: the western sky at sunset. The apples may have been suggested by stories of the oranges of Spain. The Cacus myth is thoroughly latinized, but of Greek origin. The Aventine: one of the hills of Rome. Colchis: in Asia, east of the Euxine and south of Caucasus. Mysia: province of Asia Minor, north of Lydia. The river Phasis flows through Colchis into the Euxine. For genealogy of Laomedon, see Table O (5). Pylos: it is doubtful what city is intended. There were two such towns in Elis, and one in Messenia. The word means gate (see Iliad, 5, 397), and in the case of Hercules there may be some reference to his journey to the gate or Pylos of Hades. For Alcestis, see 83; for Prometheus, 15; for the family of Dejanira, Table K. Alcides: i. e. Hercules, descendant of Alcæus. Œchalia: in Thessaly or in Eubœa. Mount Œta: in Thessaly. The Pygmies: a nation of dwarfs, so called from a Greek word meaning the cubit, or measure of about thirteen inches, which was said to be the height of these people. They lived near the sources of the Nile, or, according to others, in India. Homer tells us that the cranes used to migrate every winter to the Pygmies' country, where, attacking the cornfields, they precipitated war. H. M. Stanley, in his last African expedition, discovered a race of diminutive men that correspond fairly in appearance with those mentioned by Homer. The Cercopes: the subject of a comic poem by Homer, and of numerous grotesque representations in Greek literature and sculpture.

Interpretative. All myths of the sun represent that luminary as struggling against and overcoming monsters, or performing other laborious tasks in obedience to the orders of some tyrant of inferior spirit, but of legal authority. Since the life of Hercules is composed of such tasks, it is easy to class him with other sun-heroes. But to construe his whole history and all his feats as symbolic of the sun's progress through the heavens, beginning with the labors performed in his eastern home and ending with the capture of Cerberus in the underworld beyond the west, or to construe the subjects of the twelve labors as consciously recalling the twelve signs of the Zodiac is not only unwarranted, but absurd. To some extent Hercules is a sun-hero; to some extent his adventures are fabulous history; to a greater extent both he and his adventures are the product of generations of æsthetic, but primitive and fanciful, invention. The same statement holds true of nearly all the heroes and heroic deeds of mythology. As a matter of interest, it may be noted that the serpents that attacked Hercules in his cradle are explained as powers of darkness which the sun destroys, and the cattle that he tended, as the clouds of morning. His choice between pleasure and duty at the outset of his career enforces, of course, a lesson of conduct. His lion's skin may denote the tawny cloud which the sun trails behind him as he fights his way through the vapors that he overcomes (Cox). The slaughter of the Centaurs may be the dissipation of these vapors. His insanity may denote the raging heat of the sun at noonday. The Nemean lion may be a monster of cloud or darkness; the Hydra, a cloud that confines the kindly rains, or at times covers the heavens with numerous necks and heads of vapor. The Cerynean Stag may be a golden-tinted cloud that the sun chases; and the Cattle of the Augean stables, clouds that, refusing to burst in rain, consign the earth to drought and filth. The Erymanthian boar and the Cretan bull are probably varied forms of the powers of darkness; so also the Stamphalian (Stymphalian) birds and the giant Cacus. Finally, the scene of the hero's death is a "picture of a sunset in wild confusion, the multitude of clouds hurrying hither and thither, now hiding, now revealing the mangled body of the sun." In this way Cox, and other interpreters of myth, would explain the series. But while the explanations are entertaining and poetic, their very plausibility should suggest caution in accepting them. It is not safe to construe all the details of a mythical career in terms of any one theory. The more noble side of the character of Hercules presents itself to the moral understanding, as worthy of consideration and admiration. The dramatist Euripides has portrayed him as a great-hearted hero, high-spirited and jovial, rejoicing in the vigor of manhood, comforting the downcast, wrestling with Death and overcoming him, restoring happiness where sorrow had obtained. No grander conception of manliness has in modern times found expression in poetry than that of the Hercules in Browning's transcript of Euripides, Balaustion's Adventure.

Illustrative. Lang's translation of the Lityerses song (Theocritus, Idyl X). The song, like the Linus song, is of early origin among the laborers in the field. For Hercules, see Sir Philip Sidney, Astrophel and Stella; Spenser, Faerie Queene, 1, 11, 27; Shakespeare, Merchant of Venice, II, i; III, ii; Taming of the Shrew, I, ii; Coriolanus, IV, i; Hamlet, I, ii; Much Ado About Nothing, II, i; III, iii; King John, II, i; Titus Andronicus, IV, ii; Antony and Cleopatra, IV, x; 1 Henry VI, IV, vii; Pope, Satires, 5, 17; Milton, Paradise Lost, 11, 410 (Geryon). Amazons: Shakespeare, King John, V, ii; Midsummer Night's Dream, II, ii; 1 Henry VI, I, iv; 3 Henry VI, I, iv; Pope, Rape of the Lock, 3, 67; Hylas: Pope, Autumn; Dunciad, 2, 336.

Poems. S. Rogers, on the Torso of Hercules; Browning, Balaustion's Adventure, and Aristophanes' Apology; L. Morris, Dejaneira (Epic of Hades); William Morris, The Golden Apples (Earthly Paradise); J. H. Frere's translation of Euripides' Hercules Furens, and Plumptre's, or R. Whitelaw's (1883), of Sophocles' Women of Trachis; George Cabot Lodge, Herakles. Pygmies: James Beattie, Battle of the Pygmies and the Cranes. Dejanira: Fragment of Chorus of a "Dejaneira," by M. Arnold. Hylas: Moore (song), "When Hylas was sent with his urn to the fount," etc.; Bayard Taylor, Hylas; R. C. Rogers, Hylas; translation of Theocritus, Idyl XIII, by C. S. Calverley, 1869. Daphnis: Theocritus, Idyl I. According to this, Daphnis so loves Naïs that he defies Aphrodite to make him love again. She does so, but he fights against the new passion, and dies a victim of the implacable goddess. This song is sung by Thyrsis. Also on Daphnis, read E. Gosse's poem, The Gifts of the Muses.

In Art. Fig. 65, of a statue reproducing the style of Scopas; figs. 123-129, and opp. p. 226, in text; Heracles in the eastern pediment of the Parthenon (?); the Torso Belvedere; Farnese Hercules (National Museum, Naples); Hercules in the metopes of the Temple of Silenus (Museum, Palermo); the Infant Hercules strangling a Serpent (antique sculpture), in the Uffizi at Florence; C. G. Gleyre's painting, Hercules at the Feet of Omphale (Louvre); Bandinelli (sculpture), Hercules and Cacus; Giovanni di Bologna (sculpture), Hercules and Centaur; Amazon (ancient sculpture), in the Vatican; and Figs. 162, 185 and opp. p. 306, in text; Centaur (sculpture), Capitol, Rome; the Mad Heracles, vase picture (Monuments inédits, Rome and Paris, 1839-1878).

163-167. For the descent of Jason from Deucalion, see Table G. Iolcos: a town in Thessaly. Lemnos: in the Ægean, near Tenedos. Phineus: a son of Agenor, or of Poseidon. For the family of Medea, see Table H.

Interpretative. Argo means swift, or white, or commemorates the ship-builder, or the city of Argos. The Argo-myth rests upon a mixture of traditions of the earliest seafaring and of the course of certain physical phenomena. So far as the tradition of primitive seafaring is concerned, it may refer to some half-piratical expedition, the rich spoils of which might readily be known as the Golden Fleece. So far as the physical tradition is concerned, it may refer to the course of the year (the Ram of the Golden Fleece being the fructifying clouds that come and go across the Ægean) or to the process of sunrise and sunset (?): Helle being the glimmering twilight that sinks into the sea; Phrixus (in Greek Phrixos), the radiant sunlight; the voyage of the Argo through the Symplegades, the nocturnal journey of the sun down the west; the oak with the Golden Fleece, a symbol of the sunset which the dragon of darkness guards; the fire-breathing bulls, the advent of morning; the offspring of the dragon's teeth, an image of the sunbeams leaping from eastern darkness. Medea is a typical wise-woman or witch; daughter of Hecate and granddaughter of Asteria, the starry heavens, she comes of a family skilled in magic. Her aunt Circe was even more powerful in necromancy than she. The robe of Medea is the fleece in another form. The death of Creüsa, also called Glauce, suggests that of Hercules (in the flaming sunset?). Jason is no more faithful to his sweetheart than other solar heroes – Hercules, Perseus, Apollo – are to theirs. The sun must leave the colors and glories, the twilights and the clouds of to-day, for those of to-morrow. See Roscher, pp. 530-537. The physical explanation is more than commonly plausible. But the numerous adventures of the Argonauts are certainly survivals of various local legends that have been consolidated and preserved in the artistic form of the myth. Jason, Diáson, is another Zeus, of the Ionian race, beloved by Medea, whose name, "the counseling woman," suggests a goddess. Perhaps Medea was a local Hera-Demeter, degraded to the rank of a heroine. The Symplegades may be a reminiscence of rolling and clashing icebergs; the dove incident occurs in numerous ancient stories from that of Noah down. If Medea be another personification of morning and evening twilight, then her dragons are rays of sunlight that precede her. More likely they are part of the usual equipage of a witch, symbolizing wisdom, foreknowledge, swiftness, violence, and Oriental mystery.

Illustrative. The Argo, see Theodore Martin's translation of Catullus, LXIV (Peleus and Thetis), for the memorable launch; Pope, St. Cecilia's Day. Jason: Shakespeare, Merchant of Venice, I, i; III, ii; Æson: Merchant of Venice, V, i; Absyrtus: 2 Henry VI, V, ii. Poems: Chaucer, Legende of Good Women, 1366 (Ysiphile and Medee); W. Morris, Life and Death of Jason; Frederick Tennyson, Æson and King Athamas (in Daphne and Other Poems). Thos. Campbell's translation of the chorus in Euripides' Medea, beginning "Oh, haggard queen! to Athens dost thou guide thy glowing chariot." Translations of the Medea of Euripides have been made by Augusta Webster, 1868; by W. C. Lawton (Three Dramas of Euripides) 1889; and by Wodhull.

In Art. The terra-cotta relief (Fig. 130, text) in the British Museum; the relief from Naples, now in Vienna (Fig. 131). Figs. 132 and 133 as explained in text. Also the splendid Vengeance of Medea in the Louvre; relief on a Roman sarcophagus.

168. Textual.

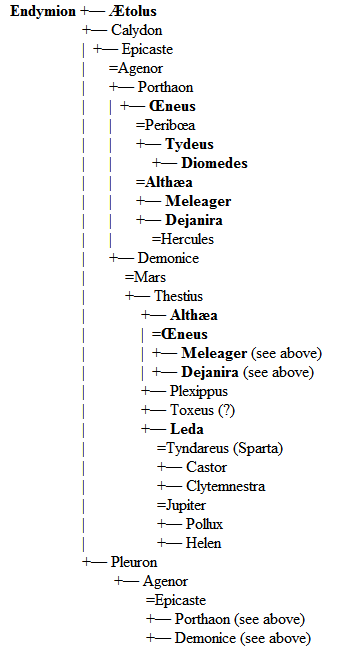

Table K. The Descendants of Ætolus (Son of Endymion)

Also, in general, Table I.

For Calydon, see Index. The Arcadian Atalanta was descended from the Arcas who was son of Jupiter and Callisto. (See Table D.)

Interpretative. Atalanta is the "unwearied maiden." She is the human counterpart of the huntress Diana. The story has of course been allegorically explained, but it bears numerous marks of local and historic origin.

Illustrative. Swinburne, Atalanta in Calydon; Margaret J. Preston, The Quenched Branch; Shakespeare, 2 Henry IV, II, ii; 2 Henry VI, I, i.

In Art. The Meleager (sculpture), in the Vatican; the Roman reliefs as in text. The original of Fig. 135 is in the Louvre.

169. The Merope story has been dramatized by Maffei (1713), Voltaire (1743), Alfieri (1783), and by others.

170-171. C. S. Calverley's The Sons of Leda, from Theocritus. Leda: Spenser, Prothalamion; Landor, Loss of Memory. Talus: the iron attendant of Artegal, Spenser, Faerie Queene, 5, 1, 12.

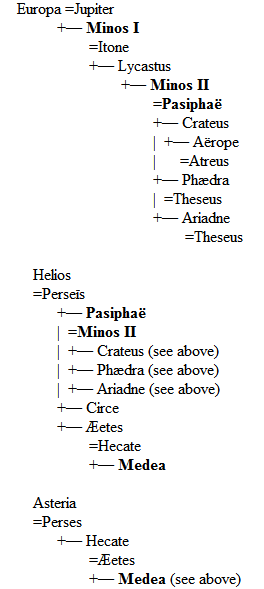

172. The Descendants of Minos I. (See also Table D.)

Table L

Interpretative. Discrimination between Minos I and Minos II is made in the text, but is rarely observed. Minos, according to Preller, is the solar king and hero of Crete; his wife, Pasiphaë, is the moon (who was worshiped in Crete under the form of a cow); and the Minotaur is the lord of the starry heavens which are his labyrinth. Others make Pasiphaë, whose name means shiner upon all, the bright heaven; and Minos (in accordance with his name, the Man, par excellence), the thinker and measurer. A lawgiver on earth, the Homeric Minos readily becomes a judge in Hades. Various fanciful interpretations, such as storm cloud, sun, etc., are given of the bull. Cox explains the Minotaur as night, devouring all things. The tribute from Athens may suggest some early suzerainty in politics and religion exercised by Crete over neighboring lands. For Mæander, see Pope, Rape of the Lock, 5, 65; Dunciad, 1, 64; 3, 55.

173. Interpretative. Dædalus is a representative of the earliest technical skill, especially in wood-cutting, carving, and the plastic arts used for industrial purposes. His flight from one land to another signifies the introduction of inventions into the countries concerned. The fall of Icarus was probably invented to explain the name of the Icarian Sea.

Illustrative. Dædalus: Chaucer, Hous of Fame, 409. Icarus: Shakespeare, 1 Henry VI, IV, vi; IV, vii; 3 Henry VI, V, vi; poem on Icarus by Bayard Taylor; travesty by J. G. Saxe.

In Art. Sculpture: Fig. 138, in text: Villa Albani, Rome; Canova's Dædalus and Icarus; painting by J. M. Vien; also by A. Pisano (Campanile, Florence).

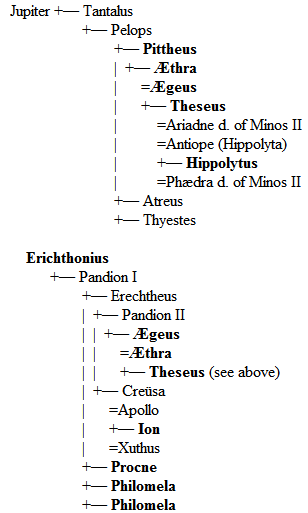

174. The descendants of Erichthonius are as follows:

Table M

Cecrops (see 65). According to one tradition, Cecrops was autochthonous and had one son, Erysichthon, who died without issue, and three daughters, Herse, Aglauros, and Pandrosos (personifications of Dew and its vivifying influences). According to another, he was of the line of Erichthonius, being either a son of Pandion I, or a son of Erechtheus and a grandson of Pandion I. Apollodorus makes him father of Pandion II. He was regarded as founder of the worship of Athene and of various civic institutions. He is probably a hero of the Pelasgian race.

Ion. According to one tradition, the race of Erechtheus became extinct, save for Ion, a son of Apollo and Creüsa, daughter of Erechtheus. This son, having been removed at birth, was brought up in Apollo's temple at Delphi, and, in accordance with the oracle of Apollo, afterwards adopted by Creüsa and her husband Xuthus (see the Ion of Euripides). Ion founded the new dynasty of Athens. But, according to Pausanias and Apollodorus, the dynasty of Erechtheus was continued by Ægeus, who was either a son, or an adopted son, of Pandion II. By Æthra he became father of Theseus, in whose veins flowed, therefore, the blood of Pelops and of Erichthonius.

Interpretative. The story of Philomela was probably invented to account for the sad song of the nightingale. With her the swallow is associated as another much loved bird of spring. Occasionally Procne is spoken of as the nightingale, and Philomela as the swallow, and Tereus as taking the form of a red-crested hoopoe.

Illustrative. Chaucer, Legende of Good Women (Philomene of Athens); Milton, Il Penseroso; Richard Barnfield, Song, "As it fell upon a day"; Thomson, Hymn on the Seasons; Swinburne, Itylus; Oscar Wilde, The Burden of Itys; Sir Thomas Noon Talfourd's drama, Ion.

176-181. Trœzen: in Argolis. According to some the Amazonian wife of Theseus was Hippolyta, but her Hercules had already killed. Theseus is said to have united the several tribes of Attica into one state, of which Athens was the capital. In commemoration of this important event, he instituted the festival of Panathenæa, in honor of Athene, the patron deity of Athens. This festival differed from the other Grecian games chiefly in two particulars. It was peculiar to the Athenians, and its chief feature was a solemn procession in which the Peplus, or sacred robe of Athene, was carried to the Parthenon, and left on or before the statue of the goddess. The Peplus was covered with embroidery, worked by select virgins of the noblest families in Athens. The procession consisted of persons of all ages and both sexes. The old men carried olive branches in their hands, and the young men bore arms. The young women carried baskets on their heads, containing the sacred utensils, cakes, and all things necessary for the sacrifices. The procession formed the subject of the bas-reliefs which embellished the frieze of the temple of the Parthenon. A considerable portion of these sculptures is now in the British Museum among those known as the "Elgin Marbles." We may mention here the other celebrated national games of the Greeks. The first and most distinguished were the Olympic, founded, it was said, by Zeus himself. They were celebrated at Olympia in Elis. Vast numbers of spectators flocked to them from every part of Greece, and from Asia, Africa, and Sicily. They were repeated every fifth year in midsummer, and continued five days. They gave rise to the custom of reckoning time and dating events by Olympiads. The first Olympiad is generally considered as beginning with the year 776 B.C. The Pythian games were celebrated in the vicinity of Delphi, the Isthmian on the Corinthian isthmus, the Nemean at Nemea, a city of Argolis. The exercises in these games were chariot-racing, running, leaping, wrestling, throwing the quoit, hurling the javelin, and boxing. Besides these exercises of bodily strength and agility, there were contests in music, poetry, and eloquence. Thus these games furnished poets, musicians, and authors the best opportunities to present their productions to the public, and the fame of the victors was diffused far and wide.

Interpretative. Theseus is the Attic counterpart of Hercules, not so significant in moral character, but eminent for numerous similar labors, and preëminent as the mythical statesman of Athens. His story may, with the usual perilous facility, be explained as a solar myth. Periphetes may be a storm cloud with its thunderbolts; the Marathonian Bull and the Minotaur may be forms of the power of darkness hidden in the starry labyrinth of heaven. Like Hercules, Theseus fights with the Amazons (clouds, we may suppose, in some form or other), and, like him, he descends to the underworld. Ariadne may be another twilight-sweetheart of the sun, and, like Medea and Dejanira, she must be deserted. She is either the "well-pleasing" or the "saintly." She was, presumably, a local nature-goddess of Naxos and Crete, who, in process of time, like Medea, sank to the condition of a heroine. Probably from her goddess-existence the marriage with Bacchus survived, to be incorporated later with the Attic myth of Theseus. As the female semblance of Bacchus, she appears to have been a promoter of vegetation; and, like Proserpina, she alternated between the joy of spring and the melancholy of winter. By some she is considered to be connected with star-worship as a moon-goddess.

Illustrative. Chaucer, The Knight's Tale (for Theseus and Ypolita); The Hous of Fame, 407, and the Legende of Good Women, 1884, for Ariadne; Shakespeare, Two Gentlemen of Verona, IV, i; Midsummer Night's Dream, II, ii (Hippolyta and Theseus); Shakespeare and Fletcher, Two Noble Kinsmen. In Beaumont and Fletcher's Maid's Tragedy, II, ii, a tapestry is ordered to be worked illustrating Theseus' desertion of Ariadne. Landor, To Joseph Ablett, "Bacchus is coming down to drink to Ariadne's love"; Landor, Theseus, and Hippolyta; Mrs. Browning, Paraphrase on Nonnus (Bacchus and Ariadne), Paraphrase on Hesiod; Sir Theodore Martin, Catullus, LXIV. Other poems: B. W. Procter, On the Statue of Theseus; Frederick Tennyson, Ariadne (Daphne and Other Poems); Mrs. Hemans, The Shade of Theseus; R. S. Ross, Ariadne in Naxos; J. S. Blackie, Ariadne; W. M. W. Call, Ariadne; Mrs. H. H. Jackson, Ariadne's Farewell. Phædra and Hippolytus: The Hippolytus of Euripides; Swinburne, Phædra; Browning, Artemis Prologizes; M. P. Fitzgerald, The Crowned Hippolytus; A. Mary F. Robinson, The Crowned Hippolytus; L. Morris, Phædra (Epic of Hades). On Cecrops: J. S. Blackie, The Naming of Athens; Erechtheus, by A. C. Swinburne.