полная версия

полная версияThe Classic Myths in English Literature and in Art (2nd ed.) (1911)

Illustrative. The second lyric of Sappho, beginning "Like to the gods he seems to me, The man that sits reclined by thee," has been translated by Phillips, by Fawkes, and by recent poets. The reference is probably to Phaon. Allusions in Pope, Moral Essays, 3, 121; 2, 24; Prologue to Satires, 309, 101; Byron's Isles of Greece, already referred to. Compare the translation in Catullus, LI.

Poems on Sappho or on Phaon: Charles Kingsley, Sappho; Buchanan, Sappho on the Leucadian Rock; Landor, – Sappho, Alcæus, Anacreon, and Phaon; Frederick Tennyson, Kleïs or the Return (in the Isles of Greece). See also Lyly's amusing prose drama, Sappho and Phao.

109. Textual. Mount Cyllene: between Arcadia and Achæa. Pierian Mountains: in Macedonia, directly north of Thessaly; the birthplace of the Muses. Pylos: an ancient city of Elis.

Interpretative. On the supposition that the herds of Apollo are the bright rays of the sun, a plausible physical explanation of the relations of Mercury (Hermes) to Apollo is the following from Max Müller: "Hermes is the god of the twilight, who betrays his equivocal nature by stealing, though only in fun, the herds of Apollo, but restoring them without the violent combat that (in the analogous Indian story) is waged for the herds between Indra, the bright god, and Vala, the robber. In India the dawn brings the light; in Greece the twilight itself is supposed to have stolen it, or to hold back the light, and Hermes, the twilight, surrenders the booty when challenged by the sun-god Apollo" (Lect. on Lang., 2 Ser., 521-522). Hermes is connected by Professor Müller with the Vedic god Sarameya, son of the twilight. Mercury, or Hermes, as morning or as evening twilight, loves the Dew, is herald of the gods, is spy of the night, is sender of sleep and dreams, is accompanied by the cock, herald of dawn, is the guide of the departed on their last journey. To the conception of twilight, Cox adds that of motion, and explains Hermes as the air in motion that springs up with the dawn, gains rapidly in force, sweeps before it the clouds (here the cattle of Apollo), makes soft music through the trees (lyre), etc. Other theorists make Hermes the Divine Activity, the god of the ether, of clouds, of storm, etc. Though the explanations of Professor Müller and the Rev. Sir G. W. Cox are more satisfactory here than usual, Roscher's the swift wind is scientifically preferable.

Illustrative. See Shelley, Homeric Hymn to Mercury, on which the text of this section is based, and passages in Prometheus Unbound; Keats, Ode to Maia.

In Art. The intent of the disguise in Fig. 81 (text) is to deceive Demeter with a sham sacrifice.

110-112. Textual. See Table E, for Bacchus, Pentheus, etc. Nysa "has been identified as a mountain in Thrace, in Bœotia, in Arabia, India, Libya; and Naxos, as a town in Caria or the Caucasus, and as an island in the Nile." Thebes: the capital of Bœotia. Mæonia: Lydia, in Asia Minor. Dia: Naxos, the largest of the Cyclades Islands in the Ægean. Mount Cithæron: in Bœotia. The Thyrsus was a wand, wreathed with ivy and surmounted by a pine cone, carried by Bacchus and his votaries. Mænads and Bacchantes were female followers of Bacchus. Bacchanal is a general term for his devotees.

Interpretative. "Bacchus (Dionysus) is regarded by many as the spiritual form of the new vernal life, the sap and pulse of vegetation and of the new-born year, especially as manifest in the vine and juice of the grape." – Lang, Myth, Ritual, etc., 2, 221 (from Preller 1, 554). The Hyades (rain-stars), that nurtured the deity, perhaps symbolize the rains that nourish sprouting vegetation. He became identified very soon with the spirituous effects of the vine. His sufferings may typify the "ruin of the summer year at the hands of storm and winter," or, perhaps, the agony of the bleeding grapes in the wine press. The orgies would, according to this theory, be a survival of the ungoverned actions of savages when celebrating a festival in honor of the deity of plenty, of harvest home, and of intoxication. But in cultivated Greece, Dionysus, in spite of the surviving orgiastic ceremonies, is a poetic incarnation of blithe, changeable, spirited youth. See Lang, Myth, Ritual, etc., 2, 221-241. That Rhea taught him would account for the Oriental nature of his rites; for Rhea is an Eastern deity by origin. The opposition of Pentheus would indicate the reluctance with which the Greeks adopted his doctrine and ceremonial. The Dionysiac worship came from Thrace, a barbarous clime; – but wandering, like the springtide, over the earth, Bacchus conquered each nation in turn. It is probable that the Dionysus-Iacchus cult was one of evangelical enthusiasm and individual cleansing from sin, of ideals in this life and of personal immortality in the next. By introducing it into Greece, Pisistratus reformed the exclusive ritual of the Eleusinian Mysteries.

Of the Festivals of Dionysus, the more important in Attica were the Lesser Dionysia, in December; the Lenæa, in January; the Anthesteria, or spring festival, in February; and the Great Dionysia, in March. These all, in greater or less degree, witnessed of the culture and the glories of the vine, and of the reawakening of the spirits of vegetation. They were celebrated, as the case might be, with a sacrifice of a victim in reminiscence of the blood by which the spirits of the departed were supposed to be nourished, with processions of women, profusion of flowers, orgiastic songs and dances, or dramatic representations.

Illustrative. Bacchus: Milton, Comus, 46. Pentheus: Landor, The Last Fruit of an Old Tree; H. H. Milman, The Bacchanals of Euripides; Calverley's and Lang's translations of Theocritus, Idyl XXVI; Thomas Love Peacock, Rhododaphne: The Vengeance of Bacchus; B. W. Procter, Bacchanalian Song. Naxos: Milton, Paradise Lost, 4, 275.

In Art. Figs. 31, 82-87, 143, in text.

113. Textual. Hesperides, see Index. River Pactolus: in Lydia. Midas: the son of one Gordius, who from a farmer had become king of Phrygia, because he happened to fulfill a prophecy by entering the public square of some city just as the people were casting about for a king. He tied his wagon in the temple of the prophetic deity with the celebrated Gordian Knot, which none but the future lord of Asia might undo. Alexander the Great undid the knot with his sword.

Interpretative. An ingenious, but not highly probable, theory explains the golden touch of Midas as the rising sun that gilds all things, and his bathing in Pactolus as the quenching of the sun's splendor in the western ocean. Midas is fabled to have been the son of the "great mother," Cybele, whose worship in Phrygia was closely related to that of Bacchus or Dionysus. The Sileni were there regarded as tutelary genii of the rivers and springs, promoting fertility of the soil. Marsyas, an inspired musician in the service of Cybele, was naturally associated in fable with Midas. The ass being the favorite animal of Silenus, the ass's ears of Midas merely symbolize his fondness for and devotion to such habits as were attributed to the Sileni. The ass, by the way, was reverenced in Phrygia; the acquisition of ass's ears may therefore have been originally a glory, not a disgrace.

Illustrative. John Lyly, Play of Mydas, especially the song, "Sing to Apollo, god of day"; Shakespeare, Merchant of Venice, III, ii (casket scene); Pope, Dunciad, 3, 342; Prologue to Satires, 82; Swift, The Fable of Midas; J. G. Saxe, The Choice of King Midas (a travesty). Gordian Knot: Henry V, I, i; Cymbeline, II, ii; Milton, Paradise Lost, 4, 348; Vacation, 90. Pactolus: Pope, Spring, 61; allusions also to the sisters of Phaëthon. Silenus, by W. S. Landor.

114-117. Textual. Mount Eryx, the vale of Enna, and Cyane are in Sicily. Eleusis: in Attica. For Arethusa see Index.

Interpretative. The Italian goddess Ceres assumed the attributes of the Greek Demeter in 496 B.C. Proserpine signifies the seed-corn which, when cast into the ground, lies there concealed, – is carried off by the god of the underworld; when the corn reappears, Proserpine is restored to her mother. Spring leads her back to the light of day. The following, from Aubrey De Vere's Introduction to his Search for Proserpine, is suggestive: "Of all the beautiful fictions of Greek Mythology, there are few more exquisite than the story of Proserpine, and none deeper in symbolical meaning. Considering the fable with reference to the physical world, Bacon says, in his Wisdom of the Ancients, that by the Rape of Proserpine is signified the disappearance of flowers at the end of the year, when the vital juices are, as it were, drawn down to the central darkness, and held there in bondage. Following up this view of the subject, the Search of her Mother, sad and unavailing as it was, would seem no unfit emblem of Autumn and the restless melancholy of the season; while the hope with which the Goddess was finally cheered may perhaps remind us of that unexpected return of fine weather which occurs so frequently, like an omen of Spring, just before Winter closes in. The fable has, however, its moral significance also, being connected with that great mystery of Joy and Grief, of Life and Death, which pressed so heavily on the mind of Pagan Greece, and imparts to the whole of her mythology a profound interest, spiritual as well as philosophical. It was the restoration of Man, not of flowers, the victory over Death, not over Winter, with which that high Intelligence felt itself to be really concerned." In Greece two kinds of Festivals, the Eleusinia and the Thesmophoria, were held in honor of Demeter and Persephone. The former was divided into the lesser, celebrated in February, and the greater (lasting nine days), in September. Distinction must be made between the Festivals and the Mysteries of Eleusis. In the Festivals all classes might participate. Those of the Spring represented the restoration of Persephone to her mother; those of the Autumn the rape of Persephone. An image of the youthful Iacchus (Bacchus) headed the procession in its march toward Eleusis. At that place and in the neighborhood were enacted in realistic fashion the wanderings and the sufferings of Demeter, the scenes in the house of Celeus, and finally the successful conclusion of the search for Persephone. The Mysteries of Eleusis were witnessed only by the initiated, and were invested with a veil of secrecy which has never been fully withdrawn. The initiates passed through certain symbolic ceremonies from one degree of mystic enlightenment to another till the highest was attained. The Lesser Mysteries were an introduction to the Greater; and it is known that the rites involved partook of the nature of purification from passion, crime, and the various degradations of human existence. By pious contemplation of the dramatic scenes presenting the sorrows of Demeter, and by participation in sacramental rites, it is probable that the initiated were instructed in the nature of life and death, and consoled with the hope of immortality (Preller). On the development of the Eleusinian Mysteries from the savage to the civilized ceremonial, see Lang, Myth, Ritual, etc., 2, 275, and Lobeck, Aglaophamus, 133.

The Thesmophoria were celebrated by married women in honor of Ceres (Demeter), and referred to institutions of married life.

That Proserpine should be under bonds to the underworld because she had partaken of food in Hades accords with a superstition not peculiar to the Greeks, but to be "found in New Zealand, Melanesia, Scotland, Finland, and among the Ojibbeways" (Lang, Myth, Ritual, etc., 2, 273).

Illustrative. Aubrey De Vere, as above; B. W. Procter, The Rape of Proserpine; R. H. Stoddard, The Search for Persephone; G. Meredith, The Appeasement of Demeter; Tennyson, Demeter and Persephone; Dora Greenwell, Demeter and Cora; T. L. Beddoes, Song of the Stygian Naiades; A. C. Swinburne, Song to Proserpine. See also notes under Persephone, 44, Demeter and Pluto. Eleusis: Schiller, Festival of Eleusis, translated by N. L. Frothingham; At Eleusis, by Swinburne. See, for poetical reference, Milton, Paradise Lost, 4, 269, "Not that fair field Of Enna," etc.; Hood, Ode to Melancholy:

Forgive if somewhile I forget,In woe to come the present bliss;As frighted Proserpine let fallHer flowers at the sight of Dis.In Art. Bernini's Pluto and Proserpine (sculpture); P. Schobelt's Rape of Proserpine (picture). Eleusinian relief: Demeter, Cora, Triptolemus (Athens); and other figures, as in text.

118. Textual. Tænarus: in Laconia. For the crime of Tantalus, see 78. In Hades he stood up to his neck in water which receded when he would drink; grapes hanging above his head withdrew when he would pluck them; while a great rock was forever just about to fall upon him. Ixion, for an insult to Juno, was lashed with serpents or brazen bands to an ever-revolving wheel. Sisyphus, for his treachery to the gods, vainly rolled a stone toward the top of a hill (see 255). For the Danaïds, see 150; Cerberus, 44, 255. The Dynast's bond: the contract with Pluto, who was Dynast or tyrant of Hades. Ferry-guard: Charon. Strymon and Hebrus: rivers of Thrace. Libethra: a city on the side of Mount Olympus, between Thessaly and Macedonia.

Interpretative. The loss of Eurydice may signify (like the death of Adonis and the rape of Proserpine) the departure of spring. Max Müller, however, identifies Orpheus with the Sanskrit Arbhu, used as a name for the Sun (Chips, etc., 2, 127). According to this explanation the Sun follows Eurydice, "the wide-spreading flush of the dawn who has been stung by the serpent of night," into the regions of darkness. There he recovers Eurydice, but while he looks back upon her she fades before his gaze, as the mists of morning vanish before the glory of the rising sun (Cox). It might be more consistent to construe Eurydice as the twilight, first, of evening which is slain by night, then, of morning which is dissipated by sunrise. Cox finds in the music of Orpheus the delicious strains of the breezes which accompany sunrise and sunset. The story should be compared with that of Apollo and Daphne, and of Mercury and Apollo. The Irish tale, The Three Daughters of King O'Hara, reverses the relation of Orpheus and Eurydice. See Curtin, Myths and Folk-Lore of Ireland, Boston, 1890.

Illustrative. Orpheus: Shakespeare, Two Gentlemen of Verona, III, ii; Merchant of Venice, V, i; Henry VIII, III, i (song); Milton, Lycidas, 58; L'Allegro, 145; Il Penseroso, 105; Pope, Ode on St. Cecilia's Day (Eurydice); Summer, 81; Southey, Thalaba (The Nightingale's Song over the Grave of Orpheus).

Poems. Wordsworth, The Power of Music; Shelley, Orpheus, a fragment; Browning, Eurydice and Orpheus; Wm. Morris, Orpheus and the Sirens (Life and Death of Jason); L. Morris, Orpheus, Eurydice (Epic of Hades); Lowell, Eurydice; E. Dowden, Eurydice; W.B. Scott, Eurydice; E.W. Gosse, The Waking of Eurydice; R. Buchanan, Orpheus, the Musician; J.G. Saxe, Travesty of Orpheus and Eurydice. On Tantalus and Sisyphus, see Spenser, Faerie Queene, 1, 5, 31-35; L. Morris, Epic of Hades.

In Art. A Relief on a tombstone in the National Museum, Naples, of Mercury, Orpheus, and Eurydice. There is also a copy in Paris of the marble in the Villa Albani, Rome. (See Fig. 94, text.) Paintings: Fig. 93, in text, by Sir Frederick Leighton; by Robert Beyschlag; by G.F. Watts; The Story of Orpheus, a series of ten paintings, by E. Burne-Jones.

119-120. Textual. Troy: the capital of Troas in Asia Minor, situated between the rivers Scamander and Simois. Famous for the siege conducted by the Greeks under Agamemnon, Menelaüs, etc. (See Chap. XXII.) Amymone: a fountain of Argolis. Enipeus: a river of Macedonia.

Interpretative. The monsters that wreak the vengeance of Neptune are, of course, his destructive storms and lashing waves.

121. For genealogy of Pelops, etc., see Tables F and I. For the misfortunes of the Pelopidæ, see 193.

Illustrative in Art. Pelops and Hippodamia; vase pictures (Monuments inédits, Rome, and Paris). East pediment, Temple of Zeus, Olympia.

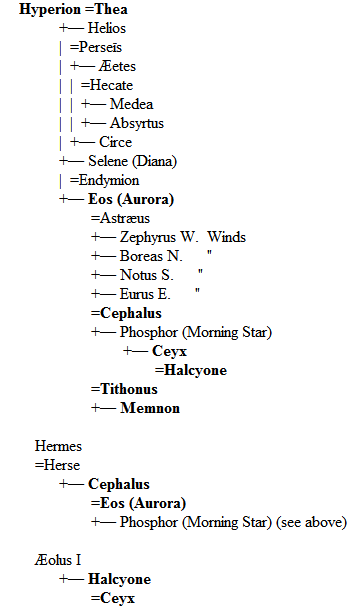

123-124. Textual. Cephalus, the son of Mercury (Hermes) and Herse, is irretrievably confounded with Cephalus, the son of Deïon and grandson of Æolus I. The former should, strictly, be regarded as the lover of Aurora (Eos); the latter is the husband of Procris, and the great-grandfather of Ulysses. (See Tables H, I, and O (4).)

Interpretative. Procris is the dewdrop (from Greek Prōx, 'dew') which reflects the shining rays of the sun. The "head of the day," or the rising sun, Cephalus, is also wooed by Aurora, the Dawn, but flies from her. The Sun slays the dew with the same gleaming darts that the dew reflects, or gives back to him. According to Preller, Cephalus is the morning-star beloved alike by Procris, the moon, and by Aurora, the dawn. The concealment of Procris in the forest and her death would, then, signify the paling of the moon before the approaching day. Hardly so probable as the former explanation.

Illustrative. Aurora: Spenser, Faerie Queene, 1, 2, 7; 1, 4, 16; Shakespeare, Midsummer Night's Dream, III, ii; Romeo and Juliet, I, i; Milton, Paradise Lost, 5, 6, "Now Morn, her rosy steps in the eastern clime Advancing," etc.; L'Allegro, 19; Landor, Gebir, "Now to Aurora borne by dappled steeds, The sacred gates of orient pearl and gold … Expanded slow," etc. Cephalus and Procris: in Moore, Legendary Ballads; Shakespeare, Midsummer Night's Dream, "Shafalus and Procrus"; A. Dobson, The Death of Procris.

In Art. Aurora: Figs. 97 and 99, as in text; paintings, by Guido Reni, as Fig. 98 in text, and by J.L. Hamon, and Guercino. Procris and Cephalus, by Turner. L'Aurore et Céphale, painted by P. Guérin, 1810, engraved by F. Forster, 1821.

125. Textual. Cimmerian country: a fabulous land in the far west, near Hades; or, perhaps, in the north, for the people dwell by the ocean that is never visited by sunlight (Odyssey, 11, 14-19). Other sons of Somnus are Icelus, who personates birds, beasts, and serpents, and Phantasus, who assumes the forms of rocks, streams, and other inanimate things.

The accompanying table will indicate the connections and descendants of Aurora.

Interpretative. According to one account, Ceyx and Halcyone, by likening their wedded happiness to that of Jupiter and Juno, incurred the displeasure of the gods. The myth springs from observation of the habits of the Halcyone-bird, which nests on the strand and is frequently bereft of its young by the winter waves. The comparison with the glory of Jupiter and Juno is suggested by the splendid iris hues of the birds. Halcyone days have become proverbial as seasons of calm. Æolus I, the son of Hellen, is here identified with Æolus III, the king of the winds. According to Diodorus, the latter is a descendant, in the fifth generation, of the former. (See Genealogical Table I.)

Illustrative. Chaucer, The Dethe of Blaunche; E. W. Gosse, Alcyone (a sonnet in dialogue); F. Tennyson, Halcyone; Edith M. Thomas, The Kingfisher; Margaret J. Preston, Alcyone. Morpheus: see Milton, Il Penseroso; Pope, Ode on St. Cecilia's Day.

126-127. Interpretative. Tithonus may be the day in its ever-recurring circuit of morning freshness, noon heat, final withering and decay (Preller); or the gray glimmer of the heavens overspread by the first ruddy flush of morning (Welcker); or, as a solar myth, the sun in his setting and waning, —Tithonus meaning, by derivation, the illuminator (Max Müller). The sleep of Tithonus in his ocean-bed, and his transformation into a grasshopper, would then typify the presumable weariness and weakness of the sun at night.

Illustrative. Spenser, Epithalamion; Faerie Queene, 1, 11, 51.

128. Textual. Mysia: province of Asia Minor, south of the Propontis, or Sea of Marmora. There is some doubt about the identification of the existing statue with that described by the ancients, and the mysterious sounds are still more doubtful. Yet there is not wanting modern testimony to their being still audible. It has been suggested that sounds produced by confined air making its escape from crevices or caverns in the rocks may have given some ground for the story. Sir Gardner Wilkinson, a traveler of the highest authority, examined the statue itself, and discovered that it was hollow, and that "in the lap of the statue is a stone, which, on being struck, emits a metallic sound that might still be made use of to deceive a visitor who was predisposed to believe its powers."

Table H. The Ancient Race of Luminaries and Winds

Interpretative. Memnon is generally represented as of dark features, lighted with the animation of glorious youth. He is king of the mythical Æthiopians who lived in the land of gloaming, where east and west met, and whose name signifies "dark splendor." His birth in this borderland of light and darkness signifies either his existence as king of an eastern land or his identity with the young sun, and strengthens the theory according to which his father Tithonus is the gray glimmer of the morning heavens. The flocks of birds have been explained as the glowing clouds that meet in battle over the body of the dead sun.

Illustrative. Milton, Il Penseroso; Drummond, Summons to Love, "Rouse Memnon's mother from her Tithon's bed"; Akenside, Pleasures of the Imagination (analogy between Memnonian music and spiritual appreciation of truth); Landor, Miscellaneous Poems, 59, "Exposed and lonely genius stands, Like Memnon in the Egyptian sands," etc.

In Art. Fig. 101, from a vase in the Louvre.

129-130. Textual. Doric pillar: the three styles of pillars in Greek architecture were Dorian, Ionic, Corinthian (see English Dictionary). Trinacria: Sicily, from its three promontories. Ægon and Daphnis: idyllic names of Sicilian shepherds (see Idyls of Theocritus and Virgil's Eclogues). Naïs: a water-nymph. For Cyclops, Galatea, Silenus, Fauns, Arethusa, see Index. Compare, with the conception of Stedman's poem, Wordsworth's Power of Music.

Illustrative. Ben Jonson, Pan's anniversary; Milton, Paradise Lost, 4. 266, 707; Paradise Regained, 2, 190; Comus, 176, 268; Pope, Autumn, 81; Windsor Forest, 37, 183; Summer, 50; Dunciad, 3, 110; Akenside, Pleasures of Imagination, "Fair Tempe! haunt beloved of sylvan Powers," etc.; On Leaving Holland, 1, 2. Poems: Fletcher, Song of the Priest of Pan, and Song of Pan (in The Faithful Shepherdess); Landor, Pan and Pitys, "Pan led me to a wood the other day," etc.; Landor, Cupid and Pan; R. Buchanan, Pan; Browning, Pan and Luna; Swinburne, Pan and Thalassius; Hon. Roden Noël, Pan, in the Modern Faust. Of course Mrs. Browning's Dead Pan cannot be appreciated unless read as a whole; nor Schiller's Gods of Greece.