полная версия

полная версияThe Classic Myths in English Literature and in Art (2nd ed.) (1911)

In Art. Fig. 58, in text, is of a marble group in the Hope Collection.

76. Textual. Clymene: a daughter of Oceanus and Tethys. Chrysolite: or gold stone, our topaz. Daystar: Phosphor, see 38 (II). Ambrosia (ἀμβρόσιος, ἄμβροτος, ἀ-βροτός), immortal, – here, "food for the immortals." Turn off to the left: indicating the course of the sun, west by south. The Serpent, or Dragon: a constellation between the Great and Little Bears. Boötes: the constellation called the Wagoner. The limits of the Scorpion were restricted by the insertion of the sign of the Scales. Athos: a mountain forming the eastern of three peninsulas south of Macedonia. Mount Taurus: in Armenia. Mount Tmolus: in Lydia. Mount Œte: between Thessaly and Ætolia, where Hercules ascended his funeral pile. Ida: the name of two mountains, – one in Crete, where Jupiter was nurtured by Amalthea, the other in Phrygia, near Troy. Mount Helicon: in Bœotia, sacred also to Apollo. Mount Hæmus: in Thrace. Ætna: in Sicily. Parnassus: in Phocis; one peak was sacred to Apollo, the other to the Muses. The Castalian Spring, sacred to the Muses, is at the foot of the mountain; Delphi is near by. Rhodope: part of the Hæmus range of mountains. Scythia: a general designation of Europe and Asia north of the Black Sea. Caucasus: between the Black and Caspian seas. Mount Ossa: associated with Mount Pelion in the story of the giants, who piled one on top of the other in their attempt to scale Olympus. These mountains, with Pindus, are in Thessaly. Libyan desert: in Africa. Libya was fabled to have been the daughter of Epaphus, king of Egypt. Tanaïs: the Don, in Scythia. Caïcus: a river of Greater Mysia, flowing into the sea at Lesbos. Xanthus and Mæander: rivers of Phrygia, flowing near Troy. Caÿster: a river of Ionia, noted for its so-called "tuneful" swans. For Nereus, Doris, Nereïds, etc., see 50 and 52. Eridanus: the mythical name of the river Po in Italy (amber was found on its banks). Naiads, see 52 (6).

Interpretative. Apollo assumed many of the attributes of Helios, the older divinity of the sun, who is ordinarily reputed to be the father of Phaëthon (ordinarily anglicized Phaëton). The name Phaëthon, like the name Phœbus, means the radiant one. The sun is called both Helios Phaëthon and Helios Phœbus in Homer. It was an easy feat of the imagination to make Phaëthon the incautious son of Helios, or Apollo, and to suppose that extreme drought is caused by his careless driving of his father's chariot. The drought is succeeded by a thunderstorm; and the lightning puts an end to Phaëthon. The rain that succeeds the lightning is, according to Cox, the tears of the Heliades. It is hardly wise to press the analogy so far, unless one is prepared to explain the amber in the same way.

Illustrative. Milman in his Samor alludes to the story. See also Chaucer, Hous of Fame, 435; Spenser, Faerie Queene, 1, 4, 9; Shakespeare, Richard II, III, iii; Two Gentlemen of Verona, III, i; 3 Henry VI, I, iv; II, vi; Romeo and Juliet, III, ii. Poems: Prior, Female Phaëton; J. G. Saxe, Phaëton; and G. Meredith, Phaëton. For description of the palace and chariot of the Sun, see Landor, Gebir, Bk. I.

In Art : Fig. 59, in text: a relief on a Roman sarcophagus in the Louvre.

77. Textual. For the siege of Troy, see Chap. XXII. Atrides (Atreides): the son of Atreus, Agamemnon. The ending -ides means son of, and is used in patronymics; for instance, Pelides (Peleides), Achilles; Tydides, Diomede, son of Tydeus. The ending -is, in patronymics, means daughter of; as Tyndaris, daughter of Tyndarus (Tyndareus), Helen; Chryseïs, daughter of Chryses.

Interpretative. Of this incident Gladstone, in his primer on Homer, says: "One of the greatest branches and props of morality for the heroic age lay in the care of the stranger and the poor… Sacrifice could not be substituted for duty, nor could prayer. Such, upon the abduction of Chryseïs, was the reply of Calchas the Seer: nothing would avail but restitution."

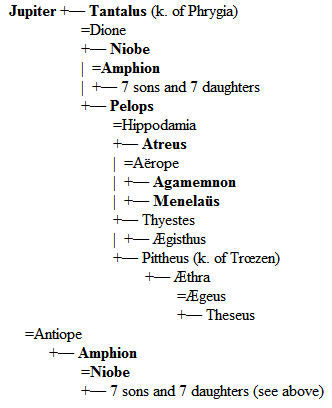

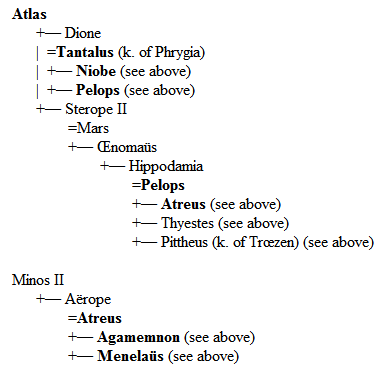

78. The Dynasty of Tantalus and its Connections. (See also Table I.)

Table F

Pelops. It is said that the goddess Demeter in a fit of absent-mindedness ate the shoulder of Pelops. The part was replaced in ivory when Pelops was restored to life. Mount Cynthus: in Delos, where Apollo and Diana were born.

Interpretative. Max Müller derives Niobe from the root snu, or snigh, from which come the words for snow in the Indo-European languages. In Latin and Greek, the stem is Niv, hence Nib, Niobe. The myth, therefore, would signify the melting of snow and the destruction of its icy offspring under the rays of the spring sun (Sci. Relig. 372). According to Homer (Iliad, 24, 611), there were six sons and six daughters. After their death no one could bury them, since all who looked on them were turned to stone. The burial was, accordingly, performed on the tenth day after the massacre, by Jupiter and the other gods. This petrifaction of the onlookers may indicate the operation of the frost. Cox says that Niobe, the snow, compares her golden-tinted, wintry mists or clouds with the splendor of the sun and moon. Others look upon the myth as significant of the withering of spring vegetation under the heats of summer (Preller). The latter explanation is as satisfactory, for spring is the child of winter (Niobe).

Illustrative. Pope, Dunciad, 2, 311; Lewis Morris, Niobe on Sipylus (Songs Unsung); Byron's noble stanza on fallen Rome, "The Niobe of nations! there she stands, Childless and crownless, in her voiceless woe," etc. (Childe Harold, 4, 79); W. S. Landor, Niobe; Frederick Tennyson, Niobe. On Tantalus, see Lewis Morris, Tantalus, in The Epic of Hades. On Sir Richard Blackmore, a physician and poor poet, Thomas Moore writes the following stanza:

'T was in his carriage the sublimeSir Richard Blackmore used to rhyme,And, if the wits don't do him wrong,'Twixt death and epics passed his time,Scribbling and killing all day long;Like Phœbus in his car at ease,Now warbling forth a lofty song,Now murdering the young Niobes.In Art. The restoration of the statue of Niobe, Mount Sipylus; of extreme antiquity. The St. Petersburg relief (Fig. 61, in text) is probably the best group. Figs. 60 and 62 are from the ancient marbles in the Uffizi, Florence. The fragments of the latter group were discovered in 1583 near the Porta San Giovanni, Rome. The figure of the mother, clasping the little girl who has run to her in terror, is one of the most admired of the ancient statues. It ranks with the Laocoön and the Apollo Belvedere among the masterpieces of art. The following is a translation of a Greek epigram supposed to relate to this statue:

To stone the gods have changed her, but in vain;The sculptor's art has made her breathe again.There is also a fine figure of a daughter of Niobe in the Vatican, Rome; and there are figures in the Louvre. Reinach in his Apollo attributes the originals to Scopas.

79. Interpretative. The month in which the festival of Linus took place was called the Lambs' Month: the days were the Lambs' Days, on one of which was a massacre of dogs. According to some, Linus was a minstrel, son of Apollo and the Muse Urania, and the teacher of Orpheus and Hercules.

80. Centaurs. Monsters represented as men from the head to the loins, while the remainder of the body was that of a horse. Centaurs are the only monsters of antiquity to which any good traits were assigned. They were admitted to the companionship of men. Chiron was the wisest and justest of the Centaurs. At his death he was placed by Jupiter among the stars as the constellation Sagittarius (the Archer). Messenia: in the Peloponnesus. Æsculapius: there were numerous oracles of Æsculapius, but the most celebrated was at Epidaurus. Here the sick sought responses and the recovery of their health by sleeping in the temple. It has been inferred from the accounts that have come down to us that the treatment of the sick resembled what is now called animal magnetism or mesmerism.

Serpents were sacred to Æsculapius, probably because of a superstition that those animals have a faculty of renewing their youth by a change of skin. The worship of Æsculapius was introduced into Rome in a time of great sickness. An embassy, sent to the temple of Epidaurus to entreat the aid of the god, was propitiously received; and on the return of the ship Æsculapius accompanied it in the form of a serpent. Arriving in the river Tiber, the serpent glided from the vessel and took possession of an island, upon which a temple was soon erected to his honor.

Interpretative. The healing powers of nature may be here symbolized. But it is more likely that the family of Asclepiadæ (a medical clan) invented Asklepios as at once their ancestor and the son of the god of healing, Apollo.

Illustrative. Milton, Paradise Lost, 9, 506; Shakespeare, Pericles, III, ii; Merry Wives, II, iii.

In Art. Æsculapius (sculpture), Vatican; also the statue in the Uffizi, Florence (text, Fig. 63). Thorwaldsen's (sculpture) Hygea (Health) and Æsculapius, Copenhagen.

81. Interpretative. Perhaps the unceasing and unvarying round of the sun led to the conception of him as a servant. Max Müller cites the Peruvian Inca who said that if the sun were free, like fire, he would visit new parts of the heavens. "He is," said the Inca, "like a tied beast who goes ever round and round in the same track" (Chips, etc., 2, 113). Nearly all Greek heroes had to undergo servitude, – Hercules, Perseus, etc. No stories are more beautiful or more lofty than those which express the hope, innate in the human heart, that somewhere and at some time some god has lived as a man among men and for the good of men. Such stories are not confined to the Greeks or the Hebrews.

Illustrative . R. Browning, Apollo and the Fates; Edith M. Thomas, Apollo the Shepherd; Emma Lazarus, Admetus; W. M. W. Call, Admetus.

83. Textual. Alcestis was a daughter of the Pelias who was killed at the instigation of Medea (167). In that affair Alcestis took no part. For her family, see Table G. She was held in the highest honor in Greek fable, and ranked with Penelope and Laodamia, the latter of whom was her niece. To explain the myth as a physical allegory would be easy, but is it not more likely that the idea of substitution finds expression in the myth? – that idea of atonement by sacrifice, which is suggested in the words of Œdipus at Colonus (185), "For one soul working in the strength of love Is mightier than ten thousand to atone." Koré (the daughter of Ceres): Proserpina. Larissa: a city of Thessaly, on the river Peneüs.

Illustrative. Milton's sonnet, On his Deceased Wife:

Methought I saw my late espousèd saintBrought to me like Alcestis from the grave,Whom Jove's great son to her glad husband gave,Rescued from death by force, though pale and faint.Chaucer, Legende of Good Women, 208 et seq.; Court of Love (?), 100 et seq.

Poems. Robert Browning's noble poem, Balaustion's Adventure, purports to be a paraphrase of the Alcestis of Euripides, but while it maintains the classical spirit, it is in execution an original poem. The Love of Alcestis, by William Morris; Mrs. Hemans, The Alcestis of Alfieri, and The Death Song of Alcestis; W. S. Landor, Hercules, Pluto, Alcestis, and Admetus; Alcestis: F. T. Palgrave, W. M. W. Call, John Todhunter (a drama).

In Art. Fig. 64, in text, Naples Museum; also the relief on a Roman sarcophagus in the Vatican.

84. Textual. This Laomedon was descended, through Dardanus (the forefather of the Trojan race), from Jupiter and the Pleiad Electra. For further information about him, see 119, 161, and Table I.

Interpretative. Apollo evidently fulfills, under Laomedon, his function as god of colonization.

85-86. Textual. For Pan, see 43; for Tmolus, 76. Peneüs: a river in Thessaly, which rises in Mount Pindus and flows through the wooded valley of Tempe. Dædal: variously adorned, variegated. Midas was king of Phrygia (see 113).

Illustrative. The story of King Midas has been told by others with some variations. Dryden, in the Wife of Bath's Tale, makes Midas' queen the betrayer of the secret:

This Midas knew, and durst communicateTo none but to his wife his ears of state.87. Illustrative. M. Arnold, Empedocles (Song of Callicles); L. Morris, Marsyas, in The Epic of Hades; Edith M. Thomas, Marsyas; E. Lee-Hamilton, Apollo and Marsyas.

In Art. Raphael's drawing, Apollo and Marsyas (Museum, Venice); Bordone's Apollo, Marsyas, and Midas (Dresden); the Græco-Roman sculpture, Marsyas (Louvre); Marsyas (or Dancing Faun), in the Lateran, Rome.

89. Textual. Daphne was a sister of Cyrene, another sweetheart of Apollo's (145). Delphi, in Phocis, and Tenedos, an island off the coast of Asia Minor, near Troy, were celebrated for their temples of Apollo. The latter temple was sacred to Apollo Smintheus, the Mouse-Apollo, probably because he had rid that country of mice as St. Patrick rid Ireland of snakes and toads. Dido: queen of Carthage (252), whose lover, Æneas, sailed away from her.

Interpretative. Max Müller's explanation is poetic though not philologically probable. "Daphne, or Ahanâ, means the Dawn. There is first the appearance of the dawn in the eastern sky, then the rising of the sun as if hurrying after his bride, then the gradual fading away of the bright dawn at the touch of the fiery rays of the sun, and at last her death or disappearance in the lap of her mother, the earth." The word Daphne also means, in Greek, a laurel; hence the legend that Daphne was changed into a laurel tree (Sci. Relig., 378, 379). Others construe Daphne as the lightning. It is, however, very probable that the Greeks of the myth-making age, finding certain plants and flowers sacred to Apollo, would invent stories to explain why he preferred the laurel, the hyacinth, the sunflower, etc. "Such myths of metamorphoses" are, as Mr. Lang says, "an universal growth of savage fancy, and spring from a want of a sense of difference between men and things" (Myth, Ritual, etc., 2, 206).

Illustrative. Shakespeare, Midsummer Night's Dream, II, ii; Taming of the Shrew, Induction ii; Troilus and Cressida, I, i; Milton, Comus, 59, 662; Hymn on the Nativity, II. 176-180, Vacation, 33-40; Paradise Lost, 4, 268-275; Paradise Regained, 2, 187; Lord de Tabley (Wm. Lancaster), Daphne, "All day long, In devious forest, Grove, and fountain side, The god had sought his Daphne," etc.; Lyly, King Mydas; Apollo's Song to Daphne; Frederick Tennyson, Daphne. Waller applies this story to the case of one whose amatory verses, though they did not soften the heart of his mistress, yet won for the poet widespread fame:

Yet what he sung in his immortal strain,Though unsuccessful, was not sung in vain.All but the nymph that should redress his wrong,Attend his passion and approve his song.Like Phœbus thus, acquiring unsought praise,He caught at love and filled his arms with bays.In Art. Fig. 67, in text; Bernini's Apollo and Daphne, in the Villa Borghese, Rome (see text, opp. p. 112). Painting: G. F. Watts' Daphne.

91. Illustrative. Hood, Flowers, "I will not have the mad Clytia, Whose head is turned by the sun," etc.; W. W. Story, Clytie; Mrs. A. Fields, Clytia. The so-called bust of Clytie (discovered not long ago) is possibly a representation of Isis.

93. Textual. Elis: northwestern part of the Peloponnesus. Alpheüs: a river of Elis flowing to the Mediterranean. The river Alpheüs does in fact disappear under ground, in part of its course, finding its way through subterranean channels, till it again appears on the surface. It was said that the Sicilian fountain Arethusa was the same stream, which, after passing under the sea, came up again in Sicily. Hence the story ran that a cup thrown into the Alpheüs appeared again in the Arethusa. It is, possibly, this fable of the underground course of Alpheüs that Coleridge has in mind in his dream of Kubla Khan:

In Xanadu did Kubla KhanA stately pleasure-dome decree:Where Alph, the sacred river, ranThrough caverns measureless to man,Down to a sunless sea.In one of Moore's juvenile poems he alludes to the practice of throwing garlands or other light objects on the stream of Alpheüs, to be carried downward by it, and afterward reproduced at its emerging, "as an offering To lay at Arethusa's feet."

The Acroceraunian Mountains are in Epirus in the northern part of Greece. It is hardly necessary to point out that a river Arethusa arising there could not possibly be approached by an Alpheüs of the Peloponnesus. Such a criticism of Shelley's sparkling verses would however be pedantic rather than just. Probably Shelley uses the word Acroceraunian as synonymous with steep, dangerous. If so, he had the practice of Ovid behind him (Remedium Amoris, 739). Mount Erymanthus: between Arcadia and Achaia. The Dorian deep: the Peloponnesus was inhabited by descendants of the fabulous Dorus. Enna: a city in the center of Sicily. Ortygia: an island on which part of the city of Syracuse is built.

Illustrative. Milton, Arcades, 30; Lycidas, 132; Margaret J. Preston, The Flight of Arethusa; Keats, Endymion, Bk. 2, "On either side out-gushed, with misty spray, A copious spring."

95. See genealogical table E for Actæon. In this myth Preller finds another allegory of the baleful influence of the dog days upon those exposed to the heat. Cox's theory that here we have large masses of cloud which, having dared to look upon the clear sky, are torn to pieces and scattered by the winds, is principally instructive as illustrating how far afield theorists have gone, and how easy it is to invent ingenious explanations.

Illustrative. Shakespeare, Merry Wives, II, i; III, ii; Titus Andronicus, II, iii; Shelley, Adonais, 31, "Midst others of less note, came one frail Form," etc., a touching allusion to himself; A. H. Clough, Actæon; L. Morris, Actæon (Epic of Hades).

96. Chios: an island in the Ægean. Lemnos: another island in the Ægean, where Vulcan had a forge.

Interpretative. The ancients were wont to glorify in fable constellations of remarkable brilliancy or form. The heavenly adventures of Orion are sufficiently explained by the text.

Illustrative. Spenser, Faerie Queene, 1, 3, 31; Milton, Paradise Lost, 1, 299, "Natheless he so endured," etc.; Longfellow, Occultation of Orion; R. H. Horne, Orion; Charles Tennyson Turner, Orion (a sonnet).

97. Electra. See genealogical table I. See same table for Merope, the mother of Glaucus and grandmother of Bellerophon (155).

Illustrative. Pleiads: Milton, Paradise Lost, 7, 374; Pope, Spring, 102; Mrs. Hemans has verses on the same subject; Byron, "Like the lost Pleiad seen no more below."

In modern sculpture, The Lost Pleiad of Randolph Rogers is famous; in painting, the Pleiades of Elihu Vedder (Fig. 72, in text).

98. Mount Latmos: in Caria. Diana is sometimes called Phœbe, the shining one. For the descendants of Endymion, the Ætolians, etc., see Table I.

Interpretative. According to the simplest explanation of the Endymion myth, the hero is the setting sun on whom the upward rising moon delights to gaze. His fifty children by Selene would then be the fifty months of the Olympiad, or Greek period of four years. Some, however, consider him to be a personification of sleep, the king whose influence comes over one in the cool caves of Latmos, "the Mount of Oblivion"; others, the growth of vegetation under the dewy moonlight; still others, euhemeristically, a young hunter, who under the moonlight followed the chase, but in the daytime slept.

Illustrative. The Endymion of Keats. Fletcher, in the Faithful Shepherdess, tells, "How the pale Phœbe, hunting in a grove, First saw the boy Endymion," etc. Young, Night Thoughts, "So Cynthia, poets feign, In shadows veiled, … Her shepherd cheered"; Spenser, Epithalamion, "The Latmian Shepherd," etc.; Marvel, Songs on Lord Fauconberg and the Lady Mary Cromwell (chorus, Endymion and Laura); O. W. Holmes, Metrical Essays, "And, Night's chaste empress, in her bridal play, Laughed through the foliage where Endymion lay."

Poems. Besides Keats' the most important are by Lowell, Longfellow, Clough (Epi Latmo, and Selene), T. B. Read, Buchanan, L. Morris (Epic of Hades). John Lyly's prose drama, Endymion, contains quaint and delicate songs.

In Art. Fig. 73, in text; Diana and the sleeping Endymion (Vatican).

Paintings. Carracci's fresco, Diana embracing Endymion (Farnese Palace, Rome); Guercino's Sleeping Endymion; G. F. Watts' Endymion.

100. Textual. Paphos and Amathus: towns in Cyprus, of which the former contained a temple to Venus. Cnidos (Cnidus or Gnidus): a town in Caria, where stood a famous statue of Venus, attributed to Praxiteles. Cytherea: Venus, an adjective derived from her island Cythera in the Ægean Sea. Acheron, and Persephone or Proserpine: see 44-48. The wind-flower of the Greeks was of bloody hue, like that of the pomegranate. It is said the wind blows the blossoms open, and afterwards scatters the petals.

Interpretative. Among the Pœnicians Venus is known as Astarte, among the Assyrians as Istar. The Adonis of this story is the Phœnician Adon, or the Hebrew Adonai, 'Lord.' The myth derives its origin from the Babylonian worship of Thammuz or Adon, who represents the verdure of spring, and whom his mistress, the goddess of fertility, seeks, after his death, in the lower regions. With their departure all birth and fruitage cease on the earth; but when he has been revived by sprinkling of water, and restored to his mistress and to earth, all nature again rejoices. The myth is akin to those of Linus, Hyacinthus, and Narcissus. Mannhardt (Wald-und Feld-kulte, 274), cited by Roscher, supplies the following characteristics common to such religious rites in various lands: (1) The spring is personified as a beautiful youth who is represented by an image surrounded by quickly fading flowers from the "garden of Adonis." (2) He comes in the early year and is beloved by a goddess of vegetation, goddess sometimes of the moon, sometimes of the star of Love. (3) In midsummer he dies, and during autumn and winter inhabits the underworld. (4) His burial is attended with lamentations, his resurrection with festivals. (5) These events take place in midsummer and in spring. (6) The image and the Adonis plants are thrown into water. (7) Sham marriages are celebrated between pairs of worshipers.