полная версия

полная версияThe Classic Myths in English Literature and in Art (2nd ed.) (1911)

36. Interpretative. Max Müller traces Hermes, child of the Dawn with its fresh breezes, herald of the gods, spy of the night, to the Vedic Saramâ, goddess of the Dawn. Others translate Saramâ, storm. Roscher derives from the same root as Sarameyas (son of Saramâ), with the meaning Hastener, the swift wind. The invention of the syrinx is attributed also to Pan.

Illustrative. To Mercury's construction of the lyre out of a tortoise shell, Gray refers (Progress of Poesy), "Parent of sweet and solemn-breathing airs, Enchanting shell!" etc. See Shakespeare, King John, IV, ii; Henry IV, IV, i; Richard III, II, i; IV, iii; Hamlet, III, iv; Milton, Paradise Lost, 3, "Though by their powerful art they bind Volatile Hermes"; 4, 717; 11, 133; Il Penseroso, 88; Comus, 637, 962. Poems: Sir T. Martin, Goethe's Phœbus and Hermes; Shelley's translation of Homer's Hymn to Mercury.

In Art. The Mercury in the Central Museum, Athens; Mercury Belvedere (Vatican); Mercury in Repose (National Museum, Naples). The Hermes by Praxiteles, in Olympia (text, opp. p. 150), and the Hermes Psychopompos leading to the underworld the spirit of a woman who has just died (text, Fig. 20; from a relief sculptured on the tomb of Myrrhina), are especially fine specimens of ancient sculpture.

In modern sculpture: Cellini's Mercury (base of Perseus, Loggia del Lanzi, Florence); Giov. di Bologna's Flying Mercury (bronze, Bargello, Florence: text, opp. p. 330); Thorwaldsen's Mercury. In modern painting: Tintoretto's Mercury and the Graces; Francesco Albani's Mercury and Apollo; Claude Lorrain's Mercury and Battus; Turner's Mercury and Argus; Raphael's allegorical Mercury (Wednesday), Vatican, Rome; and his Mercury with Psyche (Farnese Frescoes).

37. Interpretative. The name Hestia (Latin Vesta) has been variously derived from roots meaning to sit, to stand, to burn. The two former are consistent with the domestic nature of the goddess; the latter with her relation to the hearth-fire. She is "first of the goddesses," the holy, the chaste, the sacred.

Illustrative. Milton, Il Penseroso (Melancholy), "Thee bright-haired Vesta long of yore To solitary Saturn bore," etc.

38. (1) Cupid (Eros). References and allusions to Cupid throng our poetry. Only a few are here given. Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet, I, iv; Merchant of Venice, II, vi; Merry Wives, II, ii; Much Ado About Nothing, I, i; II, i; III, ii; Midsummer Night's Dream, I, i; II, ii; IV, i; Cymbeline, II, iv; Milton, Comus, 445, 1004; Herrick, The Cheat of Cupid; Pope, Rape of the Lock, 5, 102; Dunciad, 4, 308; Moral Essays, 4, 111; Windsor Forest, – on Lord Surrey, "In the same shades the Cupids tuned his lyre To the same notes of love and soft desire."

Poems. Chaucer, The Cuckow and Nightingale, or Boke of Cupid (?); Occleve, The Letter of Cupid; Beaumont and Fletcher, Cupid's Revenge, and the Masque, A Wife for a Month; J.G. Saxe, Death and Cupid, on their exchange of arrows, "And that explains the reason why Despite the gods above, The young are often doomed to die, The old to fall in love"; Thomas Ashe, The Lost Eros; Coventry Patmore, The Unknown Eros. Also John Lyly's Campaspe:

Cupid and my Campaspe playd,At cardes for kisses, Cupid payd;He stakes his quiver, bow, and arrows,His mother's doves, and teeme of sparows;Looses them too; then, downe he throwesThe corrall of his lippe, the roseGrowing on's cheek (but none knows how),With these, the cristall of his brow,And then the dimple of his chinne:All these did my Campaspe winne.At last hee set her both his eyes;Shee won, and Cupid blind did rise.O love! has shee done this to thee?What shall (alas!) become of mee?See also Lang's translation of Moschus, Idyl I, and O. Wilde, The Garden of Eros.

In Art. Antique sculpture: the Eros in Naples, ancient marble from an original perhaps by Praxiteles (text, Fig. 21); Eros bending the Bow, in the Museum at Berlin; Cupid bending his Bow (Vatican); Eros with his Bow, in the Capitoline (text, opp. p. 136).

Modern sculpture: Thorwaldsen's Mars and Cupid. Modern paintings: Bouguereau's Cupid and a Butterfly; Raphael's Cupids (among drawings in the Museum at Venice); Burne-Jones' Cupid (in series with Pyramus and Thisbe); Raphael Mengs' Cupid sharpening his Arrow; Guido Reni's Cupid; Van Dyck's Sleeping Cupid. See also under Psyche, C. 101.

Hymen. See Sir Theodore Martin's translations of the Collis O Heliconii, and the Vesper adest, juvenes, of Catullus (LXI and LXII); Milton, Paradise Lost, 11, 591; L'Allegro, 125; Pope, Chorus of Youths and Virgins.

(2) Hebe. Thomas Lodge's Sonnet to Phyllis, "Fair art thou, Phyllis, ay, so fair, sweet maid"; Milton, Vacation Exercise, 38; Comus, 290; L'Allegro, 29; Spenser, Epithalamion. Poems: T. Moore, The Fall of Hebe; J. R. Lowell, Hebe. In Art: Ary Scheffer's painting of Hebe; N. Schiavoni's painting.

Ganymede. Chaucer, Hous of Fame, 81; Tennyson, in the Palace of Art, "Or else flushed Ganymede, his rosy thigh Half-buried in the Eagle's down," etc.; Shelley in the Prometheus (Jove's order to Ganymede); Milton, Paradise Regained, 2,353; Drayton, Song 4, "The birds of Ganymed." Poems: Lord Lytton, Ganymede; Bowring, Goethe's Ganymede; Roden Noël, Ganymede; Edith M. Thomas, Homesickness of Ganymede; S. Margaret Fuller, Ganymede to his Eagle; Drummond on Ganymede's lament, "When eagle's talons bare him through the air." In Art: The Rape of Ganymede, marble in the Vatican, probably from the original in bronze by Leochares (text, Fig. 22). Græco-Roman sculpture: Ganymede and the Eagle (National Museum, Naples). Modern sculpture: Thorwaldsen's Ganymede.

(3) The Graces. Rogers, Inscription for a Temple; Matthew Arnold, Euphrosyne. These goddesses are continually referred to in poetry. Note the painting by J. B. Regnault (Louvre), also the sculpture by Canova.

(4) The Muses. Spenser, The Tears of the Muses; Milton, Il Penseroso; Byron, Childe Harold, 1, 1, 62, 88; Thomson, Castle of Indolence, 2, 2; 2, 8; Akenside, Pleasures of Imagination, 3. 280, 327; Ode on Lyric Poetry; Crabbe, The Village, Bk. 1; Introductions to the Parish Register, Newspaper, Birth of Flattery; M. Arnold, Urania. Delphi, Parnassus, etc.: Gray, Progress of Poesy, 2, 3. Vale of Tempe: Keats, On a Grecian Urn; Young, Ocean, an ode. In Art. Sculpture: Polyhymnia, ancient marble in Berlin (text, Fig. 23); Clio and Calliope, in the Vatican in Rome; Euterpe, Melpomene, Polyhymnia, and Urania, in the Louvre, Paris; Terpsichore by Thorwaldsen. Painting: Apollo and the Muses, by Raphael Mengs and by Giulio Romano; Terpsichore (picture), by Schützenberger.

(5) The Hours, in art: Raphael's Six Hours of the Day and Night.

(6) The Fates. Refrain stanzas in Lowell's Villa Franca, "Spin, spin, Clotho, spin! Lachesis, twist! and Atropos, sever!" In Art: The Fates, painting attributed to Michelangelo, but now by some to Rosso Fiorentino from Michelangelo's design (text, Fig. 24, Pitti Gallery, Florence); painting by Paul Thumann.

(7) Nemesis. For genealogy see Table B, C. 49.

(8) Æsculapius. Spenser, Faerie Queene, 1, 5, 36-43; Milton, Paradise Lost, 9, 507.

(9) (10) The Winds, Helios, Aurora, Hesper, etc. Æolus: Chaucer, Hous of Fame, 480. See C. 125 and genealogical tables H and I. Hippotades is Æolus (son of Hippotes). In Lycidas, 96, Milton calls the king of the winds Hippotades, because, following Homer (Odyssey, 10, 2) and Ovid (Metam. 14, 224), he identifies Æolus II with Æolus III. Boreas and Orithyia: Akenside, Pleasures of Imagination, 1, 722.

In Art. The fragment, Helios rising from the Sea, by Phidias, south end, east pediment of the Parthenon. Boreas and Zetos, Greek reliefs (text, Figs. 25 and 26); Boreas and Orithyia (text, Fig. 27), on a vase in Munich.

(11) Hesperus. Milton, Paradise Lost, 4, 605; 9, 49; Comus, 982; Akenside, Ode to Hesper; Campbell, Two Songs to the Evening Star, Tennyson, The Hesperides.

(12) "Iris there with humid bow waters the odorous banks," etc., Comus, 992. See also Milton's Paradise Lost, 4, 698; 11, 244. In Art: Fig. 28, text; and painting by Guy Head (Gallery, St. Luke's, Rome). She is the swift-footed, wind-footed, fleet, the Iris of the golden wings, etc.

39. Hyperborean. Beyond the North. Concerning the Elysian Plain, see 46. Illustrative: Milton, Comus, "Now the gilded car of day," etc.

40. Ceres. Illustrative. Pope, Moral Essays, 4, 176, "Another age shall see the golden ear Imbrown the slope … And laughing Ceres reassume the land"; Spring, 66; Summer, 66; Windsor Forest, 39; Gray, Progress of Poesy; Warton, First of April, "Fancy … Sees Ceres grasp her crown of corn, And Plenty load her ample horn"; Spenser, Faerie Queene, 3, 1, 51; Milton, Paradise Lost, 4, 268; 9, 395.

Poems. Tennyson, Demeter and Persephone; Mrs. H. H. Jackson, Demeter. Prose: W. H. Pater, The Myth of Demeter (Fortn. Rev. Vol. 25, 1876); S. Colvin, A Greek Hymn (Cornh. Mag. Vol. 33, 1876); Swinburne, At Eleusis.

The name Ceres is from the stem cer, Sanskrit kri, 'to make.' By metonomy the word comes to signify corn in the Latin. Demeter (Γῆ μήτηρ, δᾶ μάτηρ) means Mother Earth. The goddess is represented in art crowned with a wheat-measure (or modius), and bearing a horn of plenty filled with ears of corn. Demeter (?) appears in the group of deities on the eastern frieze of the Parthenon. Also noteworthy are the Demeter from Knidos (text, Fig. 29, from the marble in the British Museum); two statues of Ceres in the Vatican at Rome, and one in the Glyptothek at Munich; and the Roman wall painting (text, Fig. 30).

41. Rhea was worshiped as Cybele, the Great Mother, in Phrygia and at Pessinus in Galatia. During the Second Punic War, 203 B.C., her image was brought from the latter place to Rome. In 191 B.C. the Megalesian Games were first celebrated in her honor, occupying six days, from the fourth of April on. Plays were acted during this festival. The Great Mother was also called Cybebe, Berecyntia, and Dindymene.

The Cybele of Art. In works of art, Cybele exhibits the matronly air which distinguishes Juno and Ceres. Sometimes she is veiled, and seated on a throne with lions at her side; at other times she rides in a chariot drawn by lions. She wears a mural crown, that is, a crown whose rim is carved in the form of towers and battlements. Rhea is mentioned by Homer (Iliad, 15, 187) as the consort of Cronus.

Illustrative. Byron's figure likening Venice to Cybele, Childe Harold, 4, 2, "She looks a sea-Cybele, fresh from ocean," etc. Also Milton's Arcades, 21.

42. Interpretative. It is interesting to note that Homer (Iliad and Odyssey) recognizes Dionysus neither as inventor, nor as exclusive god of wine. In Iliad, 6, 130 he refers, however, to the Dionysus cult in Thrace. Hesiod is the first to call wine the gift of Dionysus. Dionysus means the Zeus or god of Nysa, an imaginary vale of Thrace, Bœotia, or elsewhere, in which the deity spent his youth. The name Bacchus owes its origin to the enthusiasm with which the followers of the god lifted up their voices in his praise. Similar names are Iacchus, Bromius, Evius (from the cry evoe). The god was also called Lyæus, the loosener of care, Liber, the liberator. His followers are also known as Edonides (from Mount Edon, in Thrace, where he was worshiped), Thyiades, the sacrificers, Lenæa and Bassarides. His festivals were the Lesser and Greater Dionysia (at Athens), the Lenæa, and the Anthesteria, in December, March, January, and February, respectively. At the first, three dramatic performances were presented.

Illustrative. A few references and allusions worth consulting: Spenser, Epithalamion; Fletcher, Valentinian, "God Lyæus, ever young"; Randolph, To Master Anthony Stafford (1632); Milton, L'Allegro, 16; Paradise Lost, 4, 279; 7, 33; Comus, 46, 522; Shakespeare, Midsummer Night's Dream, V, i; Love's Labour's Lost, IV, iii; Antony and Cleopatra, II, vii, song; Shelley, Ode to Liberty, 7, Rome – "like a Cadmæan Mænad"; Keats, To a Nightingale, "Not charioted by Bacchus and his pards." On Semele, Milton, Paradise Regained, 2, 187; Spenser, Faerie Queene, 3, 11, 33.

Poems. Ben Jonson, Dedication of the King's New Cellar; Thomas Parnell, Bacchus, or the Drunken Metamorphosis; Landor, Sophron's Hymn to Bacchus; Swinburne, Prelude to Songs before Sunrise; Roden Noël, The Triumph of Bacchus; Robert Bridges, The Feast of Bacchus; others given in text. See Index.

In Art. Of ancient representations of the Bacchus, the best examples are the marble in the British Museum (text, Fig. 31); the Silenus holding the child Bacchus (in the Louvre); the head of Dionysus found in Smyrna (now in Leyden – see text, Fig. 143), from an original of the school of Scopas; the head (now in London) from the Baths of Caracalla, of the later Attic school; the Faun and Bacchus (Museum, Naples); a standing bronze figure in Vienna, and the statue of the Villa Tiburtina (Rome). The bearded or Indian Bacchus is represented as advanced in years, grave, dignified, crowned with a diadem and robed to the feet. See also Figs. 82-87, in text.

In modern sculpture note especially the Drunken Bacchus of Michelangelo. Among modern paintings worthy of notice are Bouguereau's Youth of Bacchus, and C. Gleyre's Dance of the Bacchantes. See also under Ariadne.

43. The invention of the syrinx is attributed also to Mercury. For poetical illustrations of Pan see C. 129-138. So also for Nymphs and Satyrs.

In Art. Pan the Hunter (text, Fig. 32); the antique, Pan and Daphnis (with the syrinx) in the Museum at Naples. See references above.

44-46. It was only in rare instances that mortals returned from Hades. See the stories of Hercules, Orpheus, Ulysses, Æneas. On the tortures of the condemned and the happiness of the blessed, see 254-257 in The Adventures of Æneas.

Illustrative. Lowell, addressing the Past, says:

Whatever of true life there was in theeLeaps in our age's veins; …Here, 'mid the bleak waves of our strife and careFloat the green Fortunate IslesWhere all thy hero-spirits dwell, and shareOur martyrdom and toils;The present moves attendedWith all of brave and excellent and fairThat made the old time splendid.Milton, Paradise Lost, 3, 568, "Like those Hesperian gardens," etc. See also the same, 2, 577 ff., – "Abhorrèd Styx, the flood of deadly hate," – where the rivers of Erebus are characterized according to the meaning of their Greek names; and L'Allegro, 3. Charon: Pope, Dunciad, 3, 19; R. C. Rogers, Charon. Elysium: Cowper, Progress of Error, Night, "The balm of care, Elysium of the mind"; Milton, Paradise Lost, 3, 472; Comus, 257; L'Allegro; Shakespeare, 3 Henry VI, I, ii; Cymbeline, V, iv; Twelfth Night, I, ii; Two Gentlemen of Verona, II, vii; Shelley, To Naples. Lethe: Shakespeare, Twelfth Night, IV, i; Julius Cæsar, III, i; Hamlet, I, v; 2 Henry IV, V, ii; Milton, Paradise Lost, 2, 583. Tartarus: Milton, Paradise Lost, 2, 858; 6, 54.

47. Interpretative. The name Hades means "the invisible," or "he who makes invisible." The meaning of Pluto (Plouton), according to Plato (Cratylus), is wealth, – the giver of treasure which lies underground. Pluto carries the cornucopia, symbol of inexhaustible riches; but careful discrimination must be observed between him and Plutus (Ploutos), who is merely an allegorical figure, – a personification of wealth and nothing more. Hades is called also the Illustrious, the Many-named, the Benignant, Polydectes or the Hospitable.

Illustrative. Milton, L'Allegro, and Il Penseroso; Paradise Lost, 4, 270; Thomas Kyd, Spanish Tragedy (Andrea's descent to Hades; – this poem deals extensively with the Infernal Regions); Shakespeare, 2 Henry IV, II, iv; Troilus and Cressida, IV, iv; V, ii; Coriolanus, I, iv; Titus Andronicus, IV, iii.

Poems. Buchanan, Ades, King of Hell; Lewis Morris, Epic of Hades.

48. Proserpina. Not from the Latin pro-serpo, 'to creep forth' (used of herbs in spring), but from the Greek form Persephone, bringer of death. The later name Pherephatta refers to the doves (phatta), which were sacred to her as well as to Aphrodite. She carries ears of corn as symbol of vegetation, poppies as symbol of the sleep of death, the pomegranate as the fruit of the underworld of which none might partake and return to the light of heaven. Among the Romans her worship was overshadowed by that of Libitina, a native deity of the underworld.

Illustrative. Keats, Melancholy, 1; Spenser, Faerie Queene, 1, 2, 2; Milton, Paradise Lost, 4, 269; 9, 396.

Poems. Aubrey De Vere, The Search after Proserpine; Jean Ingelow, Persephone; Swinburne, Hymns to Proserpine; L. Morris, Persephone (Epic of Hades); D. G. Rossetti, Proserpina. (Also in crayons, in water colors, and in oil.)

In Art. Sculpture: Eastern pediment of Parthenon frieze. Painting: Lorenzo Bernini's Pluto and Proserpine; P. Schobelt's Abduction of Proserpine.

49. Textual. (1) For Æacus, son of Ægina, see 61 and C. 190, Table O; for Minos and Rhadamanthus, see 59. Eumenides: euphemistic term, meaning the well-intentioned. Hecate was descended through her father Perses from the Titans, Creüs and Eurybië; through her mother Asteria from the Titans, Cœus and Phœbe. She was therefore, on both sides, the granddaughter of Uranus and Gæa.

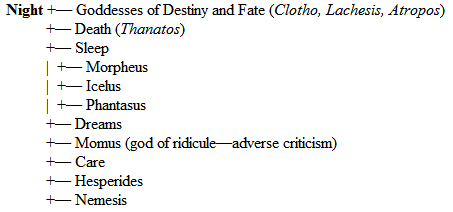

The following table is based upon Hesiod's account of The Family of Night. (Theogony.)

According to other theogonies, the Fates were daughters of Jove and Themis, and the Hesperides daughters of Atlas. The story of the true and false Dreams and the horn and ivory gates (Odyssey, 19, 560) rests on a double play upon words: (1) ἐλέφας (elephas), 'ivory,' and ἐλεφαίρομαι (elephairomai), 'to cheat with false hope'; (2) κέρας (keras), horn, and κραίνειν (krainein), 'to fulfill.' See Mortimer Collins, The Ivory Gate, a poem.

Illustrative. Hades: Milton, Paradise Lost, 2, 964; L. Morris, Epic of Hades. Styx: Shakespeare, Troilus and Cressida, V, iv; Titus Andronicus, I, ii; Milton, Paradise Lost, 2, 577; Pope, Dunciad, 2, 338. Erebus: Shakespeare, Merchant of Venice, V, i; 2 Henry IV, II, iv; Julius Cæsar, II, i. Cerberus: Spenser, Faerie Queene, 1, 11, 41; Shakespeare, Love's Labour's Lost, V, ii; 2 Henry IV, II, iv; Troilus and Cressida, II, i; Titus Andronicus, II, v; Maxwell, Tom May's Death; Milton, L'Allegro, 2. Furies: Milton, Lycidas; Paradise Lost, 2, 597, 671; 6, 859; 10, 620; Paradise Regained, 9, 422; Comus, 641; Dryden, Alexander's Feast, 6; Shakespeare, Midsummer Night's Dream, V, i; Richard III, I, iv; 2 Henry IV, V, iii. Hecate: Shakespeare, Macbeth, IV, i. Sleep and Death: Shelley, To Night; H. K. White, Thanatos.

In Art. Vase-painting of Canusium of the Underworld (text, Fig. 34); painting of a Fury by Michelangelo (Uffizi, Florence); also Figs. 35-39 in text.

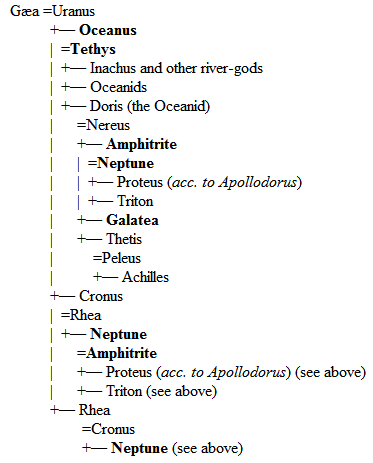

50-52. See next page for Genealogical Table, Divinities of the Sea.

For stories of the Grææ, Gorgons, Scylla, Sirens, Pleiades, etc., consult Index.

Illustrative. Oceanus: Milton, Comus, 868. Neptune: Spenser, Faerie Queene, 1, 11, 54; Shakespeare, Tempest, I, ii; Midsummer Night's Dream, II, ii; Macbeth, II, ii; Cymbeline, III, i; Hamlet, I, i; Milton, Lycidas; Paradise Regained, 1, 190; Paradise Lost, 9, 18; Comus, 869; Prior, Ode on Taking of Namur; Waller's Panegyric to the Lord Protector. Panope: Milton, Lycidas, 99.

Harpies. Milton, Paradise Lost, 3, 403. Sirens: Wm. Morris, Life and Death of Jason – Song of the Sirens. Scylla and Charybdis (see Index): Milton, Paradise Lost, 2, 660; Arcades, 63; Comus, 257; Pope, Rape of the Lock, 3, 122. Sirens: Rossetti, A Sea-Spell; A. Lang, "They hear the Sirens for the second time."

Table B. The Family of Night

Naiads. Landor, To Joseph Ablett; Shelley, To Liberty, 8; Spenser, Prothalamion, 19; Milton, Lycidas; Paradise Regained, 2, 355; Comus, 254; Buchanan, Naiad (see 134); Drummond of Hawthornden, "Nymphs, sister nymphs, which haunt this crystal brook, And happy in these floating bowers abide," etc.; Pope, Summer, 7; Armstrong, Art of Preserving Health, "Come, ye Naiads! to the fountains lead."

Table C. Divinities of the Sea

Proteus. Shakespeare, Two Gentlemen of Verona, I, i; II, ii; III, ii; IV, iv; Pope, Dunciad, 1, 37; 2, 109. The Water Deities are presented in a masque contained in Beaumont and Fletcher's Maid's Tragedy.

In Art. Poseidon: see text, Figs. 40 and 41 (originals in the British Museum and the Glyptothek, Munich); also the Isthmian Poseidon, Fig. 95. The Atlas (Græco-Roman sculpture) in National Museum, Naples; the Triton in Vatican (text, Fig. 42). Modern painting: J. Van Beers, The Siren; D. G. Rossetti, The Siren.

Textual. Consus, from condere, 'to stow away.' The sisters of Carmenta, the forward-looking Antevorta and the backward-looking Postvorta, were originally but different aspects of the function of the Muse.

54. Illustrative. Saturn: Milton, Il Penseroso; Keats, Hyperion; Peele, Arraignment of Paris. Janus, as god of civilization: Dryden, Epistle to Congreve, 7. Fauns: Milton, Lycidas; R. C. Rogers, The Dancing Faun. See Hawthorne's Marble Faun. Bellona: Shakespeare, Macbeth, "Bellona's bridegroom, lapp'd in proof"; Milton, Paradise Lost, 2, 922. Pomona: Randolph, To Master Anthony Stafford; Milton, Paradise Lost, 9, 393; 5, 378; Thomson, Seasons, Summer, 663. Flora: Milton, Paradise Lost, 5, 16; Spenser, Faerie Queene, 1, 4, 17; R. H. Stoddard, Arcadian Hymn to Flora; Pope, Windsor Forest, 38. Janus: Jonathan Swift, To Janus, on New Year's Day, 1726; Egeria, one of the Camenæ; Childe Harold, 4, 115-120; Tennyson, Palace of Art, "Holding one hand against his ear," etc. Pan, etc.: Milton, Paradise Lost, 4, 707; 4, 329.