полная версия

полная версияThe Classic Myths in English Literature and in Art (2nd ed.) (1911)

8. See Milton's Hymn on the Nativity, "Not Typhon huge ending in snaky twine." The monster is also called Typhoeus (Hesiod, Theog. 1137). The name means to smoke, to burn. The monster personifies fiery vapors proceeding from subterranean places. Other famous Giants were Mimas, Polybotes, Ephialtes, Rhœtus, Clytius. See Preller, 1, 60. Briareus (really a Centimanus) is frequently ranked among the giants.

Illustrative. Shakespeare, Troilus and Cressida, I, ii; Milton, Paradise Lost, 1, 199, and Hymn on the Nativity, 226; M. Arnold, Empedocles, Act 2; Pope, Dunciad, 4, 66. For giants, in general, see Milton, Paradise Lost, 3, 464; 11. 642, 688; Samson Agonistes, 148.

10-15. Prometheus: forethought.424 Epimetheus: afterthought. According to Æschylus (Prometheus Bound) the doom of Zeus (Jupiter) was only contingent. If he should refuse to set Prometheus free and should, therefore, ignorant of the secret, wed Thetis, of whom it was known to Prometheus that her son should be greater than his father, then Zeus would be dethroned. If, however, Zeus himself delivered Prometheus, that Titan would reveal his secret and Zeus would escape both the marriage and its fateful result. The Prometheus Unbound of Æschylus is lost; but its name indicates that in the sequel the Titan is freed from his chains. And from hints in the Prometheus Bound we gather that this liberation was to come about in the way mentioned above, Prometheus warning Zeus to marry Thetis to Peleus (whose son, Achilles, proved greater than his father, – see 191); or by the intervention of Hercules who was to be descended in the thirteenth generation from Zeus and Io (see 161 and C. 149); or by the voluntary sacrifice of the Centaur Chiron, who, when Zeus should hurl Prometheus and his rock into Hades, was destined to substitute himself for the Titan, and so by vicarious atonement to restore him to the life of the upper world. In Shelley's great drama of Prometheus Unbound, the Zeus of tyranny and ignorance and superstition is overthrown by Reason, the gift of Prometheus to mankind. Sicyon (or Mecone): a city of the Peloponnesus, near Corinth.

Illustrative. Milton, Paradise Lost, "More lovely than Pandora whom the gods endowed with all their gifts." Shakespeare, Titus Andronicus, II, i, 16.

Poems. D. G. Rossetti, Pandora; Longfellow, Masque of Pandora, Prometheus, and Epimetheus; Thos. Parnell, Hesiod, or the Rise of Woman. Prometheus, by Byron, Lowell, H. Coleridge, Robert Bridges; Prometheus Bound, by Mrs. Browning; translations of Æschylus, Prometheus Bound, Augusta Webster, E. H. Plumptre; Shelley, Prometheus Unbound; R. H. Horne, Prometheus, the Fire-bringer; E. Myers, The Judgment of Prometheus; George Cabot Lodge, Herakles, a drama. See Byron's Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte. The Golden Age: Chaucer, The Former Age (Ætas Prima); Milton, Hymn on the Nativity.

In Art. Ancient: Prometheus Unbound, vase picture (Monuments Inédits, Rome and Paris). Modern: Thorwaldsen's sculpture, Minerva and Prometheus. Pandora: Sichel (oil), Rossetti (crayons and oil), F. S. Church (water colors).

16. Dante (Durante) degli Alighieri was born in Florence, 1265. Banished by his political opponents, 1302, he remained in exile until his death, which took place in Ravenna, 1321. His Vita Nuova (New Life), recounting his ideal love for Beatrice Portinari, was written between 1290 and 1300; his great poem, the Divina Commedia (the Divine Comedy) consisting of three parts, – Inferno, Purgatorio, Paradiso, – during the years of his exile. Of the Divine Comedy, says Lowell, "It is the real history of a brother man, of a tempted, purified, and at last triumphant human soul." John Milton (b. 1608) was carried by the stress of the civil war, 1641-1649, away from poetry, music, and the art which he had sedulously cultivated, into the stormy sea of politics and war. Perhaps the severity of his later sonnets and the sublimity of his Paradise Lost, Paradise Regained, and Samson Agonistes are the fruit of the stern years of controversy through which he lived, not as a poet, but as a statesman and a pamphleteer. Cervantes (1547-1616), the author of the greatest of Spanish romances, Don Quixote. His life was full of adventure, privation, suffering, with but brief seasons of happiness and renown. He distinguished himself at the battle of Lepanto, 1571; but in 1575, being captured by Algerine cruisers, he remained five years in harsh captivity. After his return to Spain he was neglected by those in power. For full twenty years he struggled for his daily bread. Don Quixote was published in and after 1605. Corybantes: the priests of Cybele, whose festivals were violent, and whose worship consisted of dances and noise suggestive of battle.

18. Astræa was placed among the stars as the constellation Virgo, the virgin. Her mother was Themis (Justice). Astræa holds aloft a pair of scales, in which she weighs the conflicting claims of parties. The old poets prophesied a return of these goddesses and of the Golden Age. See also Pope's Messiah, —

All crimes shall cease, and ancient fraud shall fail,Returning Justice lift aloft her scale:and Milton's Hymn on the Nativity, 14, 15. In Paradise Lost, 4, 998 et seq., is a different conception of the golden scales, "betwixt Astræa and the Scorpion sign." Emerson moralizes the myth in his Astræa.

19-20. Illustrative. B. W. Procter, The Flood of Thessaly. See Ovid's famous narrative of the Four Ages and the Flood, Metamorphoses, 1, 89-415. Deucalion: Bayard Taylor, Prince Deukalion; Milton, Paradise Lost, 11, 12.

Interpretative. This myth combines two stories of the origin of the Hellenes, or indigenous Greeks, – one, in accordance with which the Hellenes, as earthborn, claimed descent from Pyrrha (the red earth); the other and older, by which Deucalion was represented as the only survivor of the flood, but still the founder of the race (Greek laós), which he created by casting stones (Greek lâes) behind him. The myth, therefore, proceeds from an unintended pun. Although, finally, Pyrrha was by myth-makers made the wife of Deucalion, the older myth of the origin of the race from stones was preserved. See Max Müller, Sci. Relig., London, 1873, p. 64.

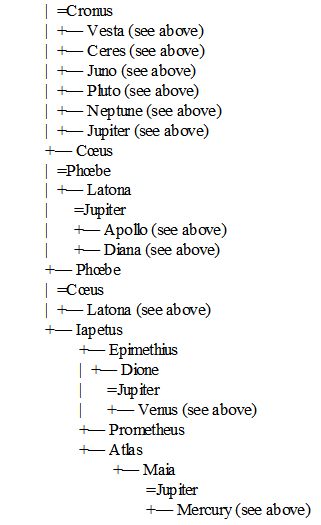

21. For genealogy of the race of Inachus, Phoroneus, Pelasgus, and Io, see Table D. Pelasgus is frequently regarded as the grandson, not the son, of Phoroneus. For the descendants of Deucalion and Hellen, see Table I of this commentary.

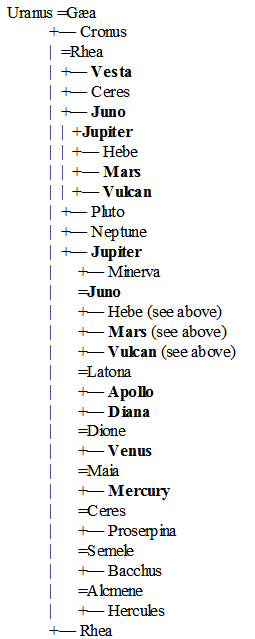

22. In the following genealogical table (A), the names of the great gods of Olympus are printed in heavy-face type. Latin forms of names or Latin substitutes are used.

Illustrative. On the Gods of Greece, see E. A. Bowring's translation of Schiller's Die Götter Griechenlands, and Bayard Taylor's Masque of the Gods. On Olympus, see Lewis Morris, The Epic of Hades. Allusions abound; e. g. Shakespeare, Troilus and Cressida, III, iii; Julius Cæsar, III, i; IV, iii; Hamlet, V, i; Milton, Paradise Lost, 1, 516; 7, 7; 10, 583; Pope, Rape of the Lock, 5, 48, and Windsor Forest, 33, 234; E. C. Stedman, News from Olympia. See also E. W. Gosse, Greece and England (On Viol and Flute).

23. The Olympian Gods. There were, according to Mr. Gladstone (No. Am. Rev. April, 1892), about twenty Olympian deities:425 (1) The five really great gods, Zeus, Hera, Poseidon, Apollo, and Athene; (2) Hephæstus, Ares, Hermes, Iris, Leto, Artemis, Themis, Aphrodite, Dione, Pæëon (or Pæon), and Hebe, – also usually present among the assembled immortals; (3) Demeter, Persephone, Dionysus, and Thetis, whose claims are more or less obscured. According to the same authority, the Distinctive Qualities of the Homeric Gods were as follows: (1) they were immortal; (2) they were incorporated in human form; (3) they enjoyed power far exceeding that possessed by mortals; (4) they were, however (with the possible exception of Athene, who is never ignorant, never deceived, never baffled), all liable to certain limitations of energy and knowledge; (5) they were subject also to corporeal wants and to human affections. The Olympian Religion, as a whole, was more careful of nations, states, public affairs, than of individuals and individual character; and in this respect, according to Mr. Gladstone. it differs from Christianity. He holds, however, that despite the occasional immoralities of the gods, their general government not only "makes for righteousness," but is addressed to the end of rendering it triumphant. Says Zeus, for instance, in the Olympian assembly, "Men complain of us the gods, and say that we are the source from whence ills proceed; but they likewise themselves suffer woes outside the course of destiny, through their own perverse offending." But, beside this general effort for the triumph of right, there is little to be said in abatement of the general proposition that, whatever be their collective conduct, the common speech of the gods is below the human level in point of morality.426

24-25. Zeus. In Sanskrit Dyaus, in Latin Jovis, in German Tiu. The same name for the Almighty (the Light or Sky) used probably thousands of years before Homer, or the Sanskrit Bible (the Vedas). It is not merely the blue sky, nor the sky personified, – not merely worship of a natural phenomenon, but of the Father who is in Heaven. So in the Vedas we find Dyaus pitar, in the Greek Zeu pater, in Latin Jupiter all meaning father of light. – Max Müller, Sci. Relig. 171, 172. Oracle: the word signifies also the answers given at the shrine.

Illustrative. Allusions to Jove on every other page of Milton, Dryden, Pope, Prior, Gray, and any poet of the Elizabethan and Augustan periods. On the Love Affairs of Jupiter and the other gods, see Milton, Paradise Regained, 2, 182. Dodona: Tennyson's Talking Oak:

That Thessalian growth,On which the swarthy ringdove sat,And mystic sentence spoke…Poem: Lewis Morris, Zeus, in The Epic of Hades.

In Art. Beside the representations of Jupiter noted in the text may be mentioned that on the eastern frieze of the Parthenon; the Jupiter Otricoli in the Vatican; also the Jupiter and Juno (painting) by Annibale Carracci; the Jupiter (sculpture) by Benvenuto Cellini.

Table A. The Great Gods of Olympus

26. Juno was called by the Romans Juno Lucina, the special goddess of childbirth. In her honor wives held the festival of the Matronalia on the first of March of each year. The Latin Juno is for Diou-n-on, from the stem Diove, and is the feminine parallel of Jovis, just as the Greek Dione (one of the loves of Zeus) is the feminine of Zeus. These names (and Diana, too) come from the root div, 'to shine,' 'to illumine.' There are many points of resemblance between the Italian Juno and the Greek Dione (identified with Hera, as Hera-Dione). Both are goddesses of the moon (?), of women, of marriage; to both the cow (with moon-crescent horns) is sacred. See Roscher, 21, 576-579. But Overbeck insists that the loves of Zeus are deities of the earth: "The rains of heaven (Zeus) do not fall upon the moon."

Illustrative. W. S. Landor, Hymn of Terpander to Juno; Lewis Morris, Heré, in The Epic of Hades.

In Art. Of the statues of Juno the most celebrated was that made by Polyclitus for her temple between Argos and Mycenæ. It was of gold and ivory. See Paus. 2, 17, 4. The goddess was seated on a throne of magnificent proportions; she wore a crown upon which were figured the Graces and the Hours; in one hand she held a pomegranate, in the other a scepter surmounted by a cuckoo. Of the extant representations of Juno the most famous are the Argive Hera (Fig. 9 in the text), the torso in Vienna from Ephesus, the Hera of the Vatican at Rome, the bronze statuette in the Cabinet of Coins and Antiquities in Vienna, the Farnese bust in the National Museum in Naples, the Ludovisi bust in the villa of that name in Rome, the Pompeian wall painting of the marriage of Zeus and Hera (given by Baumeister, Denkmäler 1, 649; see also Roscher, 13, 2127), and the Juno of Lanuvium.

27. Athenë (Athena) has some characteristics of the warlike kind in common with the Norse Valkyries, but she is altogether a more ideal conception. The best description of the goddess will be found in Homer's Iliad, 5, 730 et seq.

The derivation of Athene is uncertain (Preller). Related, say some, to æthēr, αἰθήρ, the clear upper air; say others, to the word anthos, ἄνθος, 'a flower' – virgin bloom; or (see Roscher, p. 684) to athēr, ἀθήρ, 'spear point.' Max Müller derives Athene from the root ah, which yields the Sanskrit Ahanâ and the Greek Daphne, the Dawn (?). Hence Athene is the Dawn-goddess; but she is also the goddess of wisdom, because "the goddess who caused people to wake was involuntarily conceived as the goddess who caused people to know" (Science of Language, 1, 548-551). This is poor philology.

Epithets applied to Athene are the bright-eyed, the gray-eyed, the ægis-bearing, the unwearied daughter of Zeus.

The festival of the Panathenæa was celebrated at Athens yearly in commemoration of the union of the Attic tribes. See C. 176-181.

The name Pallas characterizes the goddess as the brandisher of lightnings. Her Palladium – or sacred image – holds always high in air the brandished lance.

Minerva, or Menerva, is connected with Latin mens, Greek ménos, Sanskrit manas, 'mind'; not with the Latin mane, 'morning.' The relation is not very plausible between the awakening of the day and the awakening of thought (Max Müller, Sci. Lang, 1, 552).

For the meaning of the Gorgon, see Commentary on the myth of Perseus.

Illustrative . Byron, Childe Harold, 4, 96, the eloquent passage beginning,

Can tyrants but by tyrants conquer'd be,And Freedom find no champion and no childSuch as Columbia saw arise when sheSprung forth a Pallas, arm'd and undefiled?Shakespeare, Tempest, IV, i; As You Like It, I, iii; Winter's Tale, IV, iii; Pericles, II, iii; Milton, Paradise Lost, 4, 500; Comus, 701; Arcades, 23; Lewis Morris' Athene, in The Epic of Hades; Byron, Childe Harold, 2. 1-15, 87, 91; Ruskin's Lectures entitled "The Queen of the Air" (Athene); Thomas Woolner's Pallas Athene, in Tiresias.

In Art. The finest of the statues of this goddess was by Phidias, in the Parthenon, or temple of Athena, at Athens. The Athena of the Parthenon has disappeared; but there is good ground to believe that we have, in several extant statues and busts, the artist's conception. (See Frontispiece, the Lemnian Athena, and Fig. 53, the Hope Athena, ancient marble at Deepdene, Surrey.) The figure is characterized by grave and dignified beauty, and freedom from any transient expression; in other words, by repose. The most important copy extant is of the Roman period. The goddess was represented standing; in one hand a spear, in the other a statue of Victory. Her helmet, highly decorated, was surmounted by a Sphinx. The statue was forty feet in height, and, like the Jupiter, covered with ivory and gold. The eyes were of marble, and probably painted to represent the iris and pupil. The Parthenon, in which this statue stood, was also constructed under the direction and superintendence of Phidias. Its exterior was enriched with sculptures, many of them from the hand of the same artist. The Elgin Marbles now in the British Museum are a part of them. Also remarkable are the Minerva Bellica (Capitol, Rome); the Athena of the Acropolis Museum; the Athena of the Ægina Marbles (Glyptothek, Munich); the Minerva Medica (Vatican); the Athena of Velletri in the Louvre. (See Fig. 10.) In modern sculpture, especially excellent are Thorwaldsen's Minerva and Prometheus, and Cellini's Minerva (on the base of his Perseus). In modern painting, Tintoretto's Minerva defeating Mars.

28. While the Latin god Mars corresponds with Ares, he has also not a few points of similarity with the Greek Phœbus; for both names, Mars and Phœbus, indicate the quality shining. In Rome, the Campus Martius (field of Mars) was sacred to this deity. Here military maneuvers and athletic contests took place; here Mars was adored by sacrifice, and here stood his temple, where his priests, the Salii, watched over the sacred spear and the shield, Ancile, that fell from heaven in the reign of Numa Pompilius. Generals supplicated Mars for victory, and dedicated to him the spoils of war. See Roscher, pp. 478, 486, on the fundamental significance, philosophical and physical, of Ares. On the derivation of the Latin name Mars, see Roscher (end of article on Apollo).

Illustrative in Art. Of archaic figures, that upon the so-called François Vase in Florence represents Ares bearded and with the armor of a Homeric warrior. In the art of the second half of the fifth century B.C., he is represented as beardless, standing with spear and helmet and, generally, chlamys (short warrior's cloak); so the marble Ares statue (called the Borghese Achilles) in the Louvre. There is a later type (preferred in Rome) of the god in Corinthian helmet pushed back from the forehead, the right hand leaning on a spear, in the left a sword with point upturned, over the left arm a chlamys. The finest representation of the deity extant is the Ares Ludovisi in Rome, probably of the second half of the fourth century B.C., – a sitting figure, beautiful in form and feature, with an Eros playing at his feet. (See Fig. 11.) Modern sculpture: Thorwaldsen's relief, Mars and Cupid. Modern painting, Raphael's Mars (text, Fig. 12).

29. On the derivation of Hephæstus, see Roscher, p. 2037. From Greek aphē, 'to kindle,' or pha, 'to shine,' or spha, 'to burn.' The Latin Vulcan, while a god of fire, is not represented by the Romans as possessed of technical skill. It is said that Romulus built him a temple in Rome and instituted the Vulcanalia, – a festival in honor of the god. The name Vulcanus, or Volcanus, is popularly connected with the Latin fulgere, 'to flash' or 'lighten,' fulgur a 'flash of lightning,' etc. It is quite natural that, in many legends, fire should play an active part in the creation of man. The primitive belief of the Indo-Germanic race was that the fire-god, descending to earth, became the first man; and that, therefore, the spirit of man was composed of fire. Vulcan is also called by the Romans Mulciber, from mulceo, 'to soften.'

Illustrative. Shakespeare, Twelfth Night, V, i; Much Ado About Nothing, I, i; Troilus and Cressida, I, iii; Hamlet, III, ii; Milton, Paradise Lost, 1, 740:

From mornTo noon he fell, from noon to dewy eve,A summer's day; and with the setting sunDropt from the zenith, like a falling star,On Lemnos, the Ægean isle.In Art. Various antique illustrations are extant of the god as a smith with hammer, or at the forge (text, Fig. 13); one of him working with the Cyclopes; a vase painting of him adorning Pandora; one of him assisting at the birth of Minerva; and one of his return to Olympus led by Bacchus and Comus. Of modern paintings the following are noteworthy: J. A. Wiertz, Forge of Vulcan; Velasquez, Forge of Vulcan (Museum, Madrid) (text, Fig. 56); the Forge of Vulcan by Tintoretto. Thorwaldsen's piece of statuary, Vulcan forging Arrows for Cupid, is justly famous.

30. Castalia: on the slopes of Parnassus, sacred to Apollo and the Muses. Cephissus: in Phocis and Bœotia. (Another Cephissus flows near Athens.)

Interpretative. The birth, wanderings, return of Apollo, and his struggle with the Python, etc., are explained by many scholars as symbolic of the annual course of the sun. Apollo is born of Leto, who is, according to hypothesis, the Night from which the morning sun issues. His conflict with the dragon reminds one of Siegfried's combat and that of St. George, The dragon is variously interpreted as symbolical of darkness, mephitic vapors, or the forces of winter, which are overcome by the rays of the springtide sun. The dragon is called Delphyne, or Python. The latter name may be derived simply from that part of Phocis (Pytho) where the town of Delphi was situate, or that again from the Greek root pūth, 'to rot,' because there the serpent was left by Apollo to decay; or from the Greek pŭth, 'to inquire,' with reference to the consultation of the Delphian or Pythian oracle. "It is open to students to regard the dolphin as only one of the many animals whose earlier worship is concentrated in Apollo, or to take the creature for the symbol of spring when seafaring becomes easier to mortals, or to interpret the dolphin as the result of a volks-etymologie (popular derivation), in which the name Delphi (meaning originally a hollow in the hills) was connected with delphis, the dolphin." – Lang, Myth, Ritual, etc., 2, 197. Apollo is also called Lycius, which means, not the wolf-slayer, as is sometimes stated, for the wolf is sacred to Apollo, but either the wolf-god (as inheriting an earlier wolf-cult) or the golden god of Light. See Preller and Roscher. This derivation is more probable than that from Lycia in Asia Minor, where the god was said originally to have been worshiped. To explain certain rational myths of Apollo as referring to the annual and diurnal journeys of the sun is justifiable. To explain the savage and senseless survivals of the Apollo-myth in that way is impossible.

Festivals. The most important were as follows: (1) The Delphinia, in May, to celebrate the genial influence of the young sun upon the waters, in opening navigation, in restoring warmth and life to the creatures of the wave, especially to the dolphins, which were highly esteemed by the superstitious seafarers, fishermen, merchants, etc. (2) The Thargelia, in the Greek month of that name, our May, which heralded the approach of the hot season. The purpose of this festival was twofold: to propitiate the deity of the sun and forfend the sickness of summer; to celebrate the ripening of vegetation and return thanks for first-fruits. These festivals were held in Athens, Delos, and elsewhere. (3) The Hyacinthian fast and feast of Sparta, corresponding in both features to the Thargelian. It was held in July, in the oppressive days of the Dog Star, Sirius. (4) The Carnean of Sparta, celebrated in August. It added to the propitiatory features of the Hyacinthian, a thanksgiving for the vintage. (5) Another vintage-festival was the Pyanepsian, in Athens. (6) The Daphnephoria: "Familiar to many English people from Sir Frederick Leighton's picture. This feast is believed to have symbolized the year… An olive branch supported a central ball of brass, beneath which was a smaller ball, and thence little globes were hung." "The greater ball means the sun, the smaller the moon, the tiny globes the stars, and the three hundred and sixty-five laurel garlands used in the feast are understood to symbolize the days." (Proclus and Pausanias.) – Lang, Myth, Ritual, etc., 2. 194, 195. Apollo is also called the Sminthian, or Mouse-god, because he was regarded either as the protector or as the destroyer of mice. In the Troad mice were fed in his temple; elsewhere he was honored as freeing the country from them. As Mr. Lang says (Myth, Ritual, etc., 2, 201), this is intelligible "if the vermin which had once been sacred became a pest in the eyes of later generations."