полная версия

полная версияMythical Monsters

Such is, necessarily, the first stage of any written language, and it may, as I think, perhaps have occurred, been developed into higher stages, culminated, and perished at many successive epochs during man’s existence, presuming it to have been so extended as the progress of geology tends to affirm.

May not the meandering of the tide of civilization westward during the last three thousand years, bearing on its crest fortune and empire, and leaving in its hollow decay and oblivion, possibly be the sequel of many successive waves which have preceded it in the past, rising, some higher, some lower, as waves will.

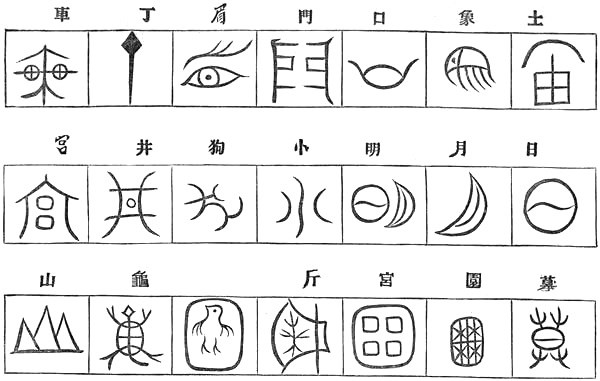

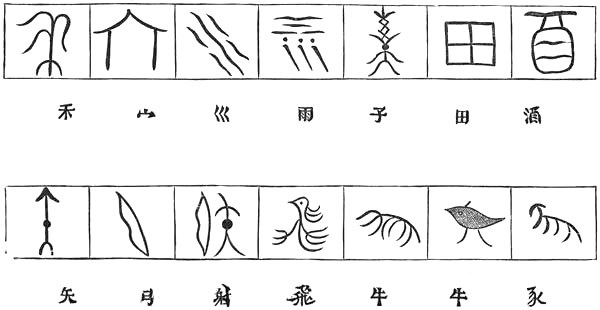

Fig. 30. – Early Chinese Hieroglyphics.

Fig. 31. – Early Chinese Hieroglyphics.

In comparison with the vast epochs of which we treat how near to us are Nineveh, Babylon, and Carthage! Yet the very sites of the former two have become uncertain, and of the last we only know by the presence of the few scattered ruins on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea. Tyre, the vast entrepôt of commerce in the days of Solomon, was stated, rightly or wrongly, by Benjamin of Tudela, to be but barely discernible (in 1173) in ruins beneath the waves; and the glory of the world, the temple of King Solomon, was represented at the same date by two copper columns which had been carried off and preserved in Rome. It is needless to quote the cases of Persia, Greece, and Rome, and of many once famous cities, which have dissolved in ruin; except as assisting to point the moral that conquest, which is always recurring, means to a great extent obliteration, the victor having no sympathy with the preservation of the time-honoured relics of the vanquished.

When decay and neglect are once initiated, the hand of man largely assists the ravages of time. The peasant carts the marbles of an emperor’s palace to his lime-kiln,90 or an Egyptian monarch strips the casing of a pyramid91 to furnish the material for a royal residence.

Nor is it beyond the limits of possibility that the arrogant caprice of some, perhaps Mongol, invader in the future, may level the imperishable pyramids themselves for the purpose of constructing some defensive work, or the gratification of an inordinate vanity.

In later dates how many comfortable modern residences have been erected from the pillage of mediæval abbey, keep, or castle? and how many fair cities92 must have fallen to decay, in Central and Eastern Asia, and how many numerous populations dwindled to insignificance since the days when Ghenghis and Timour led forth their conquering hordes, and Nadun could raise four hundred thousand horsemen93 to contest the victory with Kublai Khan.

The unconscious ploughman in Britain has for centuries guided his share above the remains of Roman villas, and the inhabitants of the later city of Hissarlik were probably as ignorant that a series of lost and buried cities lay below them, as they would have been incredulous that within a thousand years their own existence would have passed from the memory of man, and their re-discovery been due only to the tentative researches of an enthusiastic admirer of Homer. Men live by books and bards longer than by the works of their hands, and impalpable tradition often survives the material vehicle which was destined to perpetuate it. The name of Priam was still a household word when the site of his palace had been long forgotten.

The vaster a city is, the more likely is it to be constructed upon the site of its own grave, or, in other words, to occupy the broad valley of some important river beneath whose gravels it is destined to be buried.

Perched on an eminence, and based on solid rock, it may escape entombment, but more swiftly and more certainly will it be destroyed by the elements,94 and by the decomposition of its own material furnish the shroud for its envelopment.95 It is not altogether surprising then that no older discoveries than those already quoted have yet been made, for these would probably never have resulted if tradition had not both stimulated and guided the fortunate explorer.

It is, therefore, no unfair inference that the remains of equally important, but very much more ancient cities and memorials of civilization may have hitherto entirely escaped our observation, presuming that we can show some reasonable grounds for belief that, subsequent to their completion, a catastrophe has occurred of sufficiently universal a character to have obliterated entirely the annals of the past, and to have left in the possession of its few survivors but meagre and fragmentary recollections of all that had preceded them.

Now this is precisely what the history and traditions of all nations affirm to have occurred. However, as a variance of opinion exists as to the credence which should be attached to these traditions, I shall, before expressing my own views upon the subject, briefly epitomize those entertained by two authors of sufficient eminence to warrant their being selected as representatives of two widely opposite schools.

These gentlemen, to whom we are indebted for exhaustive papers,96 embracing the pith of all the information extant upon the subject, have tapped the same sources of information, consulted the same authorities, ranged their information in almost identical order, argued from the same data, and arrived at diametrically opposite conclusions.

Mr. Cheyne, following the lead of Continental mythologists, deduces that the Deluge stories were on the whole propagated from several independent centres, and adopts the theory of Schirrer and Gerland that they are ether myths, without any historical foundation, which have been transferred from the sky to the earth.

M. Lenormant, upon the other hand, eliminating from the inquiry the great inundation of China in the reign of Yao, and some others, as purely local events, concludes as the result of his researches that the story of the Deluge “is a universal tradition among all branches of the human race,” with the one exception of the black. He further argues: “Now a recollection thus precise and concordant cannot be a myth voluntarily invented. No religious or cosmogenic myth presents this character of universality. It must arise from the reminiscences of a real and terrible event, so powerfully impressing the imagination of the first ancestors of our race, as never to have been forgotten by their descendants. This cataclysm must have occurred near the first cradle of mankind and before the dispersion of families from which the different races of men were to spring.”

Lord Arundel of Wardour adopts a similar view in many respects to that of M. Lenormant, but argues for the existence of a Deluge tradition in Egypt, and the identity of the Deluge of Yu (in China) with the general catastrophe of which the tradition is current in other countries.

The subject is in itself so inviting, and has so direct a bearing upon the argument of this work that I propose to re-examine the same materials and endeavour to show from them that the possible solutions of the question have not yet been exhausted.

We have as data: —

1. The Biblical account.

2. That of Josephus.

3. The Babylonian.

4. The Hindu.

5. The Chinese.

6. The traditions of all nations in the northern hemisphere, and of certain in the southern.

It is unnecessary to travel in detail over the well-worn ground of the myths and traditions prevalent among European nations, the presumed identity of Noah with Saturn, Janus, and the like, or the Grecian stories of Ogyges and Deucalion. Nor is anyone, I think, disposed to dispute the identity of the cause originating the Deluge legends in Persia and in India. How far these may have descended from independent sources it is now difficult to determine, though it is more than probable that their vitality is due to the written Semitic records. Nor is it necessary to discuss any unimportant differences which may exist between the text of Josephus and that of the Bible, which agree sufficiently closely, but are mere abstracts (with the omission of many important details) in comparison with the Chaldæan account. This may be accounted for by their having been only derived from oral tradition through the hands of Abraham. The Biblical narrative shows us that Abraham left Chaldæa on a nomadic enterprise, just as a squatter leaves the settled districts of Australia or America at the present day, and strikes out with a small following and scanty herd to search for, discover, and occupy new country; his destiny leading him, may be for a few hundred, may be for a thousand miles. In such a train there is no room for heavy baggage, and the stone tablets containing the detailed history of the Deluge would equally with all the rest of such heavy literature be left behind.

The tradition, however reverenced and faithfully preserved at first, would, under such circumstances, soon get mutilated and dwarfed. We may, therefore, pass at once to the much more detailed accounts presented in the text of Berosus, and in the more ancient Chaldæan tablets deciphered by the late Mr. G. Smith from the collation of three separate copies.

The account by Berosus (see Appendix) was taken from the sacred books of Babylon, and is, therefore, of less value than the last-mentioned as being second-hand. The leading incidents in his narrative are similar to those contained in that of Genesis, but it terminates with the vanishing of Xisuthros (Noah) with his wife, daughter, and the pilot, after they had descended from the vessel and sacrificed to the gods, and with the return of his followers to Babylon. They restored it, and disinterred the writings left (by the pious obedience of Xisuthros) in Shurippak, the city of the Sun.

The great majority of mythologists appear to agree in assigning a much earlier date to the Deluge, than that which has hitherto been generally accepted as the soundest interpretation of the chronological evidence afforded by the Bible.

I have never had the advantage of finding the arguments on which this opinion is based, formulated in association, although, as incidentally referred to by various authors, they appear to be mainly deduced from the references made, both by sacred and profane writers, to large populations and important cities existing subsequently to the Deluge, but at so early a date, as to imply the necessity of a very long interval indeed between the general annihilation caused by the catastrophe, and the attainment of so high a pitch of civilization and so numerous a population as their existence implies.

Philologists at the same time declare that a similar inference may be drawn from the vast periods requisite for the divergence of different languages from the parent stock,97 while the testimony of the monuments and sculptures of ancient Egypt assures us that race distinction of as marked a type as occurs at the present day existed at so early a date98 as to preclude the possibility of the derivation of present nations from the descendants of Noah within the limited period usually allowed.

These difficulties vanish, if we consider the Biblical and Chaldean narratives as records of a local catastrophe, of vast extent perhaps, and resulting in general but not total destruction, whose sphere may have embraced the greater portion of Western Asia, and perhaps Europe; but which, while wrecking the great centres of northern civilization, did not extend southwards to Africa and Egypt.99 The Deluge legends indigenous in Mexico at the date of the Spanish conquest, combining the Biblical incidents of the despatch of birds from a vessel with the conception of four consecutive ages terminating in general destruction, and corresponding with the four ages or Yugas of India, supply in themselves the testimony of their probable origin from Asia. The cataclysm which caused what is called the Deluge may or may not have extended to America, probably not. In a future page I shall enumerate a few of the resemblances between the inhabitants of the New World and of the Old indicative of their community of origin.

I refer the reader to M. Lenormant’s valuable essay100 for his critical notice on the dual composition of the account in Genesis, derived as it appears to be from two documents, one of which has been called the Elohistic and the other the Jehovistic account, and for his comparison of it with the Chaldean narrative exhumed by the late Mr. George Smith from the Royal Library of Nineveh, the original of which is probably of anterior date to Moses, and nearly contemporaneous with Abraham.

I transcribe from M. Lenormant the text of the Chaldean narrative, because there are points in it which have not yet been commented on, and which, as it appears to me, assist in the solution of the Deluge story: —

I will reveal to thee, O Izdhubar, the history of my preservation – and tell to thee the decision of the gods.

The town of Shurippak, a town which thou knowest, is situated on the Euphrates. It was ancient, and in it [men did not honour] the gods. [I alone, I was] their servant, to the great gods – [The gods took counsel on the appeal of] Anu – [a deluge was proposed by] Bel – [and approved by Nabon, Nergal and] Adar.

And the god [Êa,] the immutable lord, – repeated this command in a dream. – I listened to the decree of fate that he announced, and he said to me: – “Man of Shurippak, son of Ubaratutu – thou, build a vessel and finish it [quickly]. – By a [deluge] I will destroy substance and life. – Cause thou to go up into the vessel the substance of all that has life. – The vessel thou shalt build – 600 cubits shall be the measure of its length – and 60 cubits the amount of its breadth and of its height. – [Launch it] thus on the ocean and cover it with a roof.” – I understood, and I said to Êa, my lord: – “[The vessel] that thou commandest me to build thus, – [when] I shall do it – young and old [shall laugh at me].” – [Êa opened his mouth and] spoke. – He said to me, his servant: – “[If they laugh at thee] thou shalt say to them: [Shall be punished] he who has insulted me, [for the protection of the gods] is over me. – … like to caverns … – … I will exercise my judgment on that which is on high and that which is below … – … Close the vessel … – … At a given moment that I shall cause thee to know, – enter into it, and draw the door of the ship towards thee. – Within it, thy grains, thy furniture, thy provisions, – thy riches, thy men-servants, and thy maid-servants, and thy young people – the cattle of the field and the wild beasts of the plain that I will assemble – and that I will send thee, shall be kept behind thy door.” – Khasisatra opened his mouth and spoke; – he said to Êa, his lord: – “No one has made [such a] ship. – On the prow I will fix … – I shall see … and the vessel … – the vessel thou commandest me to build [thus] – which in …101

On the fifth day [the two sides of the bark] were raised. – In its covering fourteen in all were its rafters – fourteen in all did it count above. – I placed its roof and I covered it. – I embarked in it on the sixth day; I divided its floors on the seventh; – I divided the interior compartments on the eighth. I stopped up the chinks through which the water entered in; – I visited the chinks and added what was wanting. – I poured on the exterior three times 3,600 measures of asphalte, – and three times 3,600 measures of asphalte within. – Three times 3,600 men, porters, brought on their heads the chests of provisions. – I kept 3,600 chests for the nourishment of my family, – and the mariners divided amongst themselves twice 3,600 chests. – For [provisioning] I had oxen slain; – I instituted [rations] for each day. – In [anticipation of the need of] drinks, of barrels and of wine – [I collected in quantity] like to the waters of a river, [of provisions] in quantity like to the dust of the earth. – [To arrange them in] the chests I set my hand to. – … of the sun … the vessel was completed. – … strong and – I had carried above and below the furniture of the ship. – [This lading filled the two-thirds.]

All that I possessed I gathered together; all I possessed of silver I gathered together; all that I possessed of gold I gathered – all that I possessed of the substance of life of every kind I gathered together. – I made all ascend into the vessel; my servants male and female, – the cattle of the fields, the wild beasts of the plains, and the sons of the people, I made them all ascend.

Shamash (the sun) made the moment determined, and – he announced it in these terms: – “In the evening I will cause it to rain abundantly from heaven; enter into the vessel and close the door.” – The fixed moment had arrived, which he announced in these terms: “In the evening I will cause it to rain abundantly from heaven.” – When the evening of that day arrived, I was afraid, – I entered into the vessel and shut my door. – In shutting the vessel, to Buzurshadirabi, the pilot, – I confided this dwelling with all that it contained.

Mu-sheri-ina-namari102– rose from the foundations of heaven in a black cloud; – Ramman103 thundered in the midst of the cloud – and Nabon and Sharru marched before; – they marched, devastating the mountain and the plain; – Nergal104 the powerful, dragged chastisements after him; – Adar105 advanced, overthrowing before him; – the archangels of the abyss brought destruction, – in their terrors they agitated the earth. – The inundation of Ramman swelled up to the sky, – and [the earth] became without lustre, was changed into a desert.

They broke … of the surface of the [earth] like …; – [they destroyed] the living beings of the surface of the earth. – The terrible [Deluge] on men swelled up to [heaven]. – The brother no longer saw his brother; men no longer knew each other. In heaven – the gods became afraid of the waterspout, and – sought a refuge; they mounted up to the heaven of Anu.106– The gods were stretched out motionless, pressing one against another like dogs. – Ishtar wailed like a child, – the great goddess pronounced her discourse: – “Here is humanity returned into mud, and – this is the misfortune that I have announced in the presence of the gods. So I announced the misfortune in the presence of the gods, – for the evil I announced the terrible [chastisement] of men who are mine. – I am the mother who gave birth to men, and – like to the race of fishes, there they are filling the sea; – and the gods by reason of that – which the archangels of the abyss are doing, weep with me.” – The gods on their seats were seated in tears, – and they held their lips closed, [revolving] future things.

Six days and as many nights passed; the wind, the waterspout, and the diluvian rain were in all their strength. At the approach of the seventh day the diluvian rain grew weaker, the terrible waterspout – which had assailed after the fashion of an earthquake – grew calm, the sea inclined to dry up, and the wind and the waterspout came to an end. I looked at the sea, attentively observing – and the whole of humanity had returned to mud; like unto sea-weeds the corpses floated. I opened the window, and the light smote on my face. I was seized with sadness; I sat down and I wept; – and my tears came over my face.

I looked at the regions bounding the sea; towards the twelve points of the horizon; not any continent. – The vessel was borne above the land of Nizir, – the mountain of Nizir arrested the vessel, and did not permit it to pass over. – A day and a second day the mountain of Nizir arrested the vessel, and did not permit it to pass over; – the third and fourth day the mountain of Nizir arrested the vessel, and did not permit it to pass over; – the fifth and sixth day the mountain of Nizir arrested the vessel, and did not permit it to pass over. – At the approach of the seventh day, I sent out and loosed a dove. The dove went, turned, and – found no place to light on, and it came back. I sent out and loosed a swallow; the swallow went, turned, and – found no place to light on, and it came back. I sent out and loosed a raven; the raven went, and saw the corpses on the waters; it ate, rested, turned, and came not back.

I then sent out (what was in the vessel) towards the four winds, and I offered a sacrifice. I raised the pile of my burnt-offering on the peak of the mountain; seven by seven I disposed the measured vases,107– and beneath I spread rushes, cedar, and juniper wood. The gods were seized with the desire of it, – the gods were seized with a benevolent desire of it; – and the gods assembled like flies above the master of the sacrifice. From afar, in approaching, the great goddess raised the great zones that Anu has made for their glory (the gods’).108 These gods, luminous crystal before me, I will never leave them; in that day I prayed that I might never leave them. “Let the gods come to my sacrificial pile! – but never may Bel come to my sacrificial pile! for he did not master himself, and he has made the waterspout for the Deluge, and he has numbered my men for the pit.”

From far, in drawing near, Bel – saw the vessel, and Bel stopped; – he was filled with anger against the gods and the celestial archangels: – “No one shall come out alive! No man shall be preserved from the abyss!” – Adar opened his mouth and said; he said to the warrior Bel: – “What other than Ea should have formed this resolution? – for Ea possesses knowledge and [he foresees] all.” – Ea opened his mouth and spake; he said to the warrior Bel: – “O thou, herald of the gods, warrior, – as thou didst not master thyself, thou hast made the waterspout of the deluge. – Let the sinner carry the weight of his sins, the blasphemer the weight of his blasphemy. – Please thyself with this good pleasure, and it shall never be infringed; faith in it never [shall be violated]. – Instead of thy making a new deluge, let hyænas appear and reduce the number of men; instead of thy making a new deluge, let there be famine, and let the earth be [devastated]; – instead of thy making a new deluge, let Dibbara109 appear, and let men be [mown down]. – I have not revealed the decision of the great gods; – it is Khasisatra who interpreted a dream and comprehended what the gods had decided.”

Then, when his resolve was arrested, Bel entered into the vessel. – He took my hand and made me rise. – He made my wife rise, and made her place herself at my side. – He turned around us and stopped short; he approached our group. – “Until now Khasisatra has made part of perishable humanity; – but lo, now, Khasisatra and his wife are going to be carried away to live like the gods, – and Khasisatra will reside afar at the mouth of the rivers.” – They carried me away and established me in a remote place at the mouth of the streams.

This narrative agrees with the Biblical one in ascribing the inundation to a deluge of rain; but adds further details which connect it with intense atmospheric disturbance, similar to that which would be produced by a series of cyclones, or typhoons, of unusual severity and duration.

The intense gloom, the deluge of rain, terrific violence of wind, and the havoc both on sea and land, which accompany the normal cyclones occurring annually on the eastern coast of China, and elsewhere, and lasting but a few hours in any one locality, can hardly be credited, except by those who have experienced them. They are, however, sufficient to render explicable the general devastation and loss of life which would result from the duration of typhoons, or analogous tempests, of abnormal intensity, for even the limited period of six days and nights allotted in the text above, and much more so for that of one hundred and fifty days assigned to it in the Biblical account.

As illustrating this I may refer to a few calamities of recent date, which, though of trivial importance in comparison with the stupendous event under our consideration, bring home to us the terribly devastating power latent in the elements.

In Bengal, a cyclone on October 31, 1876, laid under water three thousand and ninety-three square miles, and destroyed two hundred and fifteen thousand lives.

A typhoon which raged in Canton, Hongkong, and Macao on September 22, 1874, besides much other destruction, destroyed several thousand people in Macao and the adjacent villages, the number of corpses in the town being so numerous that they had to be gathered in heaps and burnt with kerosene, the population, without the Chinese who refused to lend assistance, being insufficient to bury them.