полная версия

полная версияMythical Monsters

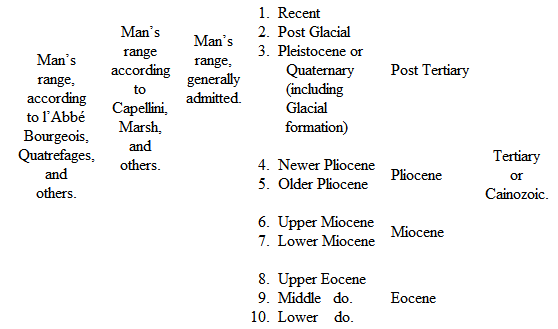

Comparatively recent – comparatively, that is to say, with regard to the vast æons that preceded them, but extending back over enormous spaces of time when contrasted with the limited duration of written history, – they embrace the period during which the mainly existing distribution of land and ocean has obtained, and the present forms of life have appeared by evolution from preceding species, or, as some few still maintain, by separate and special creation.

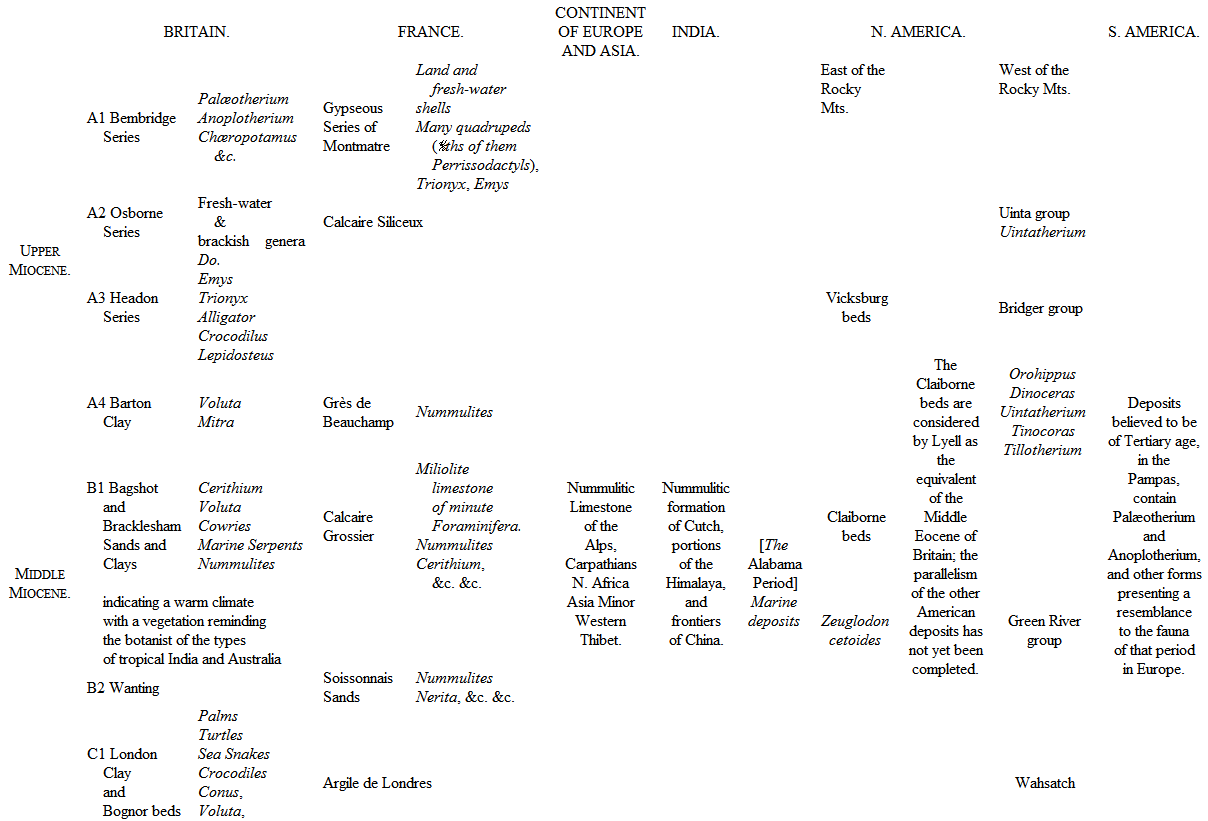

THE TERTIARY OR CAINOZOIC AGE.

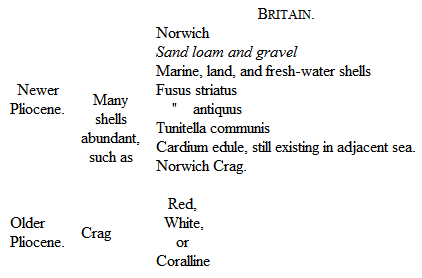

PLIOCENE.

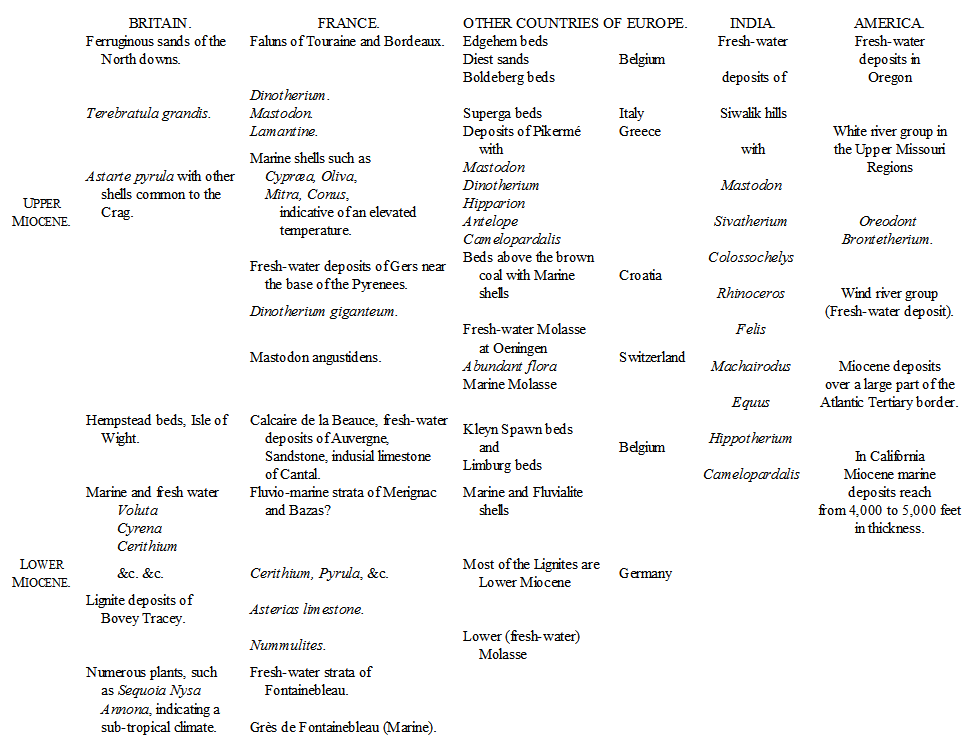

MIOCENE.

The subdivisions of the Eocene have been worked out in great detail in Britain, France, and America. Those of most other countries have either not yet been fully studied or their exact equivalence remains undetermined.

We learn, both from the nature of these deposits and from their organic contents, that climatic oscillations have been passing during the whole period of their deposition over the surface of the globe, and inducing corresponding fluctuations in the character of the vegetable and animal life abounding on it. A complete collation of these varying conditions at synchronous periods remains to be achieved, but the study of our own country, and those adjacent to it, shows that alternations of tropical, boreal, and temperate climate have occurred in it; a remarkable series of conditions which has only lately been thoroughly and satisfactorily accounted for.

Thus, during a portion of the Eocene period a tropical climate prevailed, as is evidenced by deposits containing remains of palms of an equatorial type, crocodiles, turtles, tropical shells, and other remains attesting the existence of a high temperature. The converse is proved of the Pleistocene by the existence of a boreal fauna, and the widespread evidences of glacial action. The gradations of climate during the Miocene and Pliocene, and the amelioration subsequent to the glacial period, have resulted in the gradual development or appearance of specific life as it exists at present.

Corresponding indications of secular variability of climate are derived from all quarters: during the Miocene age, Greenland (in N. Lat. 70°) developed an abundance of trees, such as the yew, the Redwood, a Sequoia allied to the Californian species, beeches, planes, willows, oaks, poplars, and walnuts, as well as a Magnolia and a Zamia. In Spitzbergen (N. Lat. 78° 56′) flourished yews, hazels, poplars, alders, beeches, and limes. At the present day, a dwarf willow and a few herbaceous plants form the only vegetation, and the ground is covered with almost perpetual ice and snow.

Many similar fluctuations of climate have been traced right back through the geological record; but this fact, though interesting in relation to the general solution of the causes, has little bearing on the present purpose.

Sir Charles Lyell conceived that all cosmical changes of climate in the past might be accounted for by the varying preponderance of land in the vicinity of the equator or near the poles, supplemented, of course, in a subordinate degree by alteration of level and the influence of ocean currents. When, for example, at any geological period the excess of land was equatorial, the ascent and passage northwards of currents of heated air would, according to his view, render the poles habitable; while, per contrâ, the excessive massing of land around the pole, and absence of it from the equator, would cause an arctic climate to spread far over the now temperate latitudes.

The correctness of these inferences has been objected to by Mr. James Geikie and Dr. Croll, who doubt whether the northward currents of air would act as successful carriers of heat to the polar regions, or whether they would not rather dissipate it into space upon the road. On the other hand, Mr. Geikie, though admitting that the temperature of a large unbroken arctic continent would be low, suggests that, as the winds would be stripped of all moisture on its fringes, the interior would therefore be without accumulations of snow and ice; and in the more probable event of its being deeply indented by fjords and bays, warm sea-currents (the representatives of our present Gulf and Japan streams, but possessing a higher temperature than either, from the greater extent of equatorial sea-surface originating them, and exposed to the sun’s influence) would flow northward, and, ramifying, carry with them warm and heated atmospheres far into its interior, though even these, he thinks, would be insufficient in their effects under any circumstances to produce the sub-tropical climates which are known to have existed in high latitudes.

Mr. John Evans75 has thrown out the idea that possibly a complete translation of geographical position with respect to polar axes may have been produced by a sliding of the whole surface crust of the globe about a fluid nucleus. This, he considers, would be induced by disturbances of equilibrium of the whole mass from geological causes. He further points out that the difference between the polar and equatorial diameters of the globe, which constitutes an important objection to his theory, is materially reduced when we take into consideration the enormous depth of the ocean over a large portion of the equator, and the great tracts of land elevated considerably above the sea-level in higher latitudes. He also speculates on the general average of the surface having in bygone geological epochs approached much more nearly to that of a sphere than it does at the present time.

Sir John Lubbock favoured the idea of a change in the position of the axis of rotation, and this view has been supported by Sir H. James76 and many later geologists.77 If I apprehend their arguments correctly, this change could only have been produced by what may be termed geological revolutions. These are great outbursts of volcanic matter, elevations, subsidences, and the like. These having probably been almost continuous throughout geological time, incessant changes, small or great, would be demanded in the position of the axis, and the world must be considered as a globe rolling over in space with every alteration of its centre of gravity. The possibility of this view must be left for mathematicians and astronomers to determine.

Sounder arguments sustain the theory propounded by Dr. Croll (though this, again, is not universally accepted), that all these alterations of climate can be accounted for by the effects of nutation, and the precession of the equinoxes. From these changes, combined with the eccentricity of the ecliptic from the first, it results that at intervals of ten thousand five hundred years, the northern and southern hemispheres are alternately in aphelion during the winter, and in perihelion during the summer months, and vice versâ; or, in other words, that if at any given period the inclination of the earth’s axis produces winter in the northern hemisphere, while the earth is at a maximum distance from that focus of its orbit in which the sun is situated, then, after an interval of ten thousand five hundred years, and as a result of the sum of the backward motion of the equinoxes along the ecliptic, at the rate of 50′ annually, the converse will obtain, and it will be winter in the northern hemisphere while the earth is at a minimum distance from the sun.

The amount of eccentricity of the ecliptic varies greatly during long periods, and has been calculated for several million years back. Mr. Croll78 has demonstrated a theory explaining all great secular variations of climate as indirectly the result of this, through the action of sundry physical agencies, such as the accumulation of snow and ice, and especially the deflection of ocean currents. From a consideration of the tables which he has computed of the eccentricity and longitude of the earth’s orbit, he refers the glacial epoch to a period commencing about two hundred and forty thousand years back, and extending down to about eighty thousand years ago, and he describes it as “consisting of a long succession of cold and warm periods; the warm periods of the one hemisphere corresponding in time with the cold periods of the other, and vice versâ.”

Having thus spoken of the processes adopted for estimating the duration of geological ages, and the results which have been arrived at, with great probability of accuracy, in regard to some of the more recent, it now only remains to briefly state the facts from which the existence of man, during these latter periods, has been demonstrated. The literature of this subject already extends to volumes, and it is therefore obviously impossible, in the course of the few pages which the limits of this work admit, to give anything but the shortest abstract, or to assign the credit relatively due to the numerous progressive workers in this rich field of research. I therefore content myself with taking as my text-book Mr. James Geikie’s Prehistoric Europe, the latest and most exhaustive work upon the subject, and summarizing from it the statements essential to my purpose.

From it we learn that, long prior to the ages when men were acquainted with the uses of bronze and iron, there existed nations or tribes, ignorant of the means by which these metals are utilized, whose weapons and implements were formed of stone, horn, bone, and wood.

These, again, may be divided into an earlier and a later race, strongly characterized by the marked differences in the nature of the stone implements which they respectively manufactured, both in respect to the material employed and the amount of finish bestowed upon it. To the two periods in which these people lived the terms Palæolithic and Neolithic have been respectively applied, and a vast era is supposed to have intervened between the retiring from Europe of the one and the appearance there of the other.

Palæolithic man was contemporaneous with the mammoth (Elephas primigenius), the woolly rhinoceros (Rhinoceros primigenius), the Hippopotamus major, and a variety of other species, now quite extinct, as well as with many which, though still existing in other regions, are no longer found in Europe; whereas the animals contemporaneous with Neolithic man were essentially the same as those still occupying it.

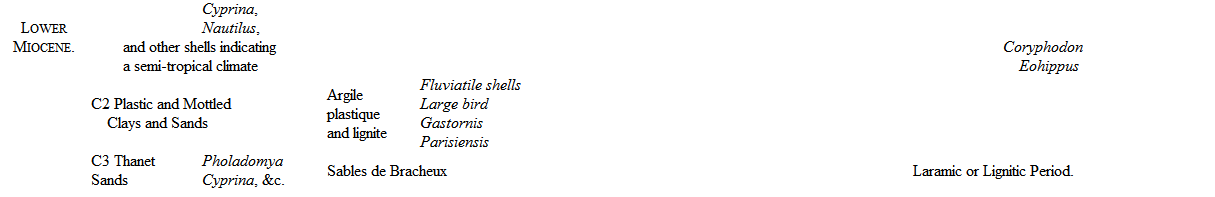

Fig. 19. – Engraving by Palæolithic Man on Reindeer Antler.79

(The two sides of the same piece of antler are here represented.)

The stone implements of Palæolithic man had but little variety of form, were very rudely fashioned, being merely chipped into shape, and never ground or polished; they were worked nearly entirely out of flint and chert. Those of Neolithic man were made of many varieties of hard stone, often beautifully finished, frequently ground to a sharp point or edge, and polished all over.

Palæolithic men were unacquainted with pottery and the art of weaving, and apparently had no domesticated animals or system of cultivation; but the Neolithic lake dwellers of Switzerland had looms, pottery, cereals, and domesticated animals, such as swine, sheep, horses, dogs, &c.

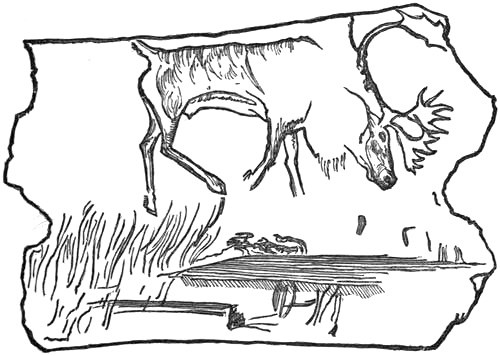

Implements of horn, bone, and wood were in common use among both races, but those of the older are frequently distinguished by their being sculptured with great ability or ornamented with life-like engravings of the various animals living at the period; whereas there appears to have been a marked absence of any similar artistic ability on the part of Neolithic man.

Fig. 20. – Reindeer engraved on Antler by Palæolithic Man. (After Geikie.)

Again, it is noticeable that, while the passage from the Neolithic age into the succeeding bronze age was gradual, and, indeed, that the use of stone implements and, in some parts, weapons, was contemporaneous with that of bronze in other places, no evidence exists of a transition from Palæolithic into Neolithic times. On the contrary, the examination of bone deposits, such as those of Kent’s Cave and Victoria Cave in England, and numerous others in Belgium and France, attest “beyond doubt that a considerable period must have supervened after the departure of Palæolithic man and before the arrival of his Neolithic successor.” The discovery of remains of Palæolithic man and animals in river deposits in England and on the Continent, often at considerable elevations80 above the existing valley bottoms, and in Löss, and the identification of the Pleistocene or Quaternary period with Preglacial and Glacial times, offer a means of estimating what that lapse of time must have been.81

Skeletons or portions of the skeletons of human beings, of admitted Palæolithic age, have been found in caverns in the vicinity of Liege in Belgium, by Schmerling, and probably the same date may be assigned those from the Neanderthal Cave near Düsseldorf. A complete skeleton, of tall stature, of probable but not unquestioned Palæolithic age, has also been discovered in the Cave of Mentone on the Riviera.

These positive remains yield us further inferences than can be drawn from the mere discovery of implements or fragmentary bones associated with remains of extinct animals.

The Mentone man, according to M. Rivière, had a rather long but large head, a high and well-made forehead, and the very large facial angle of 85°. In the Liege man the cranium was high and short, and of good Caucasian type; “a fair average human skull,” according to Huxley.

Other remains, such as the jaw-bone from the cave of the Naulette in Belgium, and the Neanderthal skeleton, show marks of inferiority; but even in the latter, which was the lowest in grade, the cranial capacity is seventy-five cubic inches or “nearly on a level with the mean between the two human extremes.”

We may, therefore, sum up by saying that evidences have been accumulated of the existence of man, and intelligent man, from a period which even the most conservative among geologists are unable to place at less than thirty thousand years; while most of them are convinced both of his existence from at least later Pliocene times, and of the long duration of ages which has necessarily elapsed since his appearance – a duration to be numbered, not by tens, but by hundreds of thousands of years.

Fig. 21. – Engraving by Palæolithic Man on Reindeer Antler.

CHAPTER IV.

THE DELUGE NOT A MYTH

If we assume that the antiquity of man is as great, or even approximately as great, as Sir Charles Lyell and his followers affirm, the question naturally arises, what has he been doing during those countless ages, prior to historic times? what evidences has he afforded of the possession of an intelligence superior to that of the brute creation by which he has been surrounded? what great monuments of his fancy and skill remain? or has the sea of time engulphed any that he erected, in abysses so deep that not even the bleached masts project from the surface, to testify to the existence of the good craft buried below?

These questions have been only partially asked, and but slightly answered. They will, however, assume greater proportions as the science of archæology extends itself, and perhaps receive more definite replies when fresh fields for investigation are thrown open in those portions of the old world which Asiatic reserve has hitherto maintained inviolable against scientific prospectors.

If man has existed for fifty thousand years, as some demand, or for two hundred thousand, as others imagine, has his intelligence gone on increasing thoughout the period? and if so, in what ratio? Are the terms of the series which involve the unknown quantity stated with sufficient precision to enable us to determine whether his development has been slow, gradual, and more or less uniform, as in arithmetical, or gaining at a rapidly increasing rate, as in geometric progression. Or, to pursue the simile, could it be more accurately expressed by the equation to a curve which traces an ascending and descending path, and, though controlled in reality by an absolute law, appears to exhibit an unaccountable and capricious variety of positive and negative phases, of points d’arrêt, nodes, and cusps.

These questions cannot yet be definitely answered; they may be proposed and argued on, but for a time the result will doubtless be a variety of opinions, without the possibility of solution by a competent arbiter.

For example, it is a matter of opinion whether the intelligence of the present day is or is not of a higher order than that which animated the savans of ancient Greece. It is probable that most would answer in the affirmative, so far as the question pertains to the culture of the masses only, but how will scholars decide, who are competent to compare the works of our present poets, sculptors, dramatists, logicians, philosophers, historians, and statesmen, with those of Homer, Pindar, Œschylus, Euripides, Herodotus, Aristotle, Euclid, Phidias, Plato, Solon, and the like? Will they, in a word, consider the champions of intellect of the present day so much more robust than their competitors of three thousand years ago as to render them easy victors? This would demonstrate a decided advance in human intelligence during that period; but, if this is the case, how is it that all the great schools and universities still cling to the reverential study of the old masters, and have, until quite recently, almost ignored modern arts, sciences, and languages.

We must remember that the ravages of time have put out of court many of the witnesses for the one party to the suit, and that natural decay, calamity, and wanton destruction82 have obliterated the bulk of the philosophy of past ages. With the exceptions of the application of steam, the employment of moveable type in printing,83 and the utilization of electricity, there are few arts and inventions which have not descended to us from remote antiquity, lost, many of them, for a time, some of them for ages, and then re-discovered and paraded as being, really and truly, something new under the sun.

Neither must we forget the oratory and poetry, the masterpieces of logical argument, the unequalled sculptures, and the exquisitely proportioned architecture of Greece, or the thorough acquaintance with mechanical principles and engineering skill evinced by the Egyptians, in the construction of the pyramids, vast temples, canals84 and hydraulic works.85

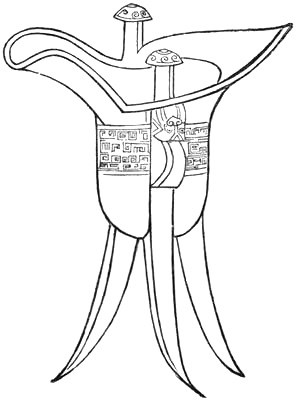

Notice, also, the high condition of civilization possessed by the Chinese four thousand years ago, their enlightened and humane polity, their engineering works,86 their provision for the proper administration of different departments of the State, and their clear and intelligent documents.87

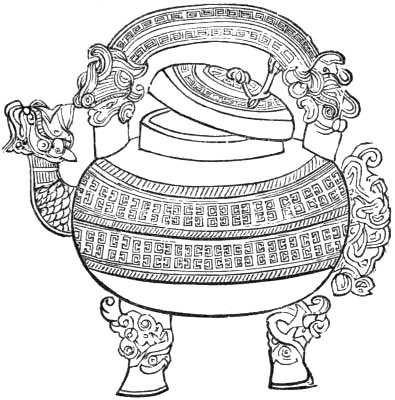

Fig. 23. – Vase. Han Dynasty,

B.C. 206 to A.D. 23.

(From the Poh Ku T’u.)

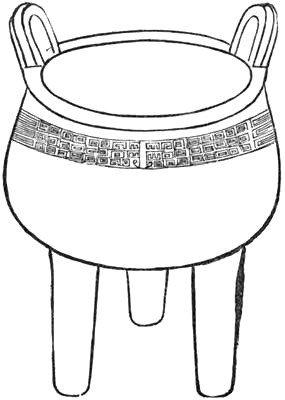

Fig. 24. – Cyathus or Cup for Libations.Shang Dynasty, B.C. 1766 to B.C. 1122.

(From the Poh Ku T’u.)

In looking back upon these, I think we can hardly distinguish any such deficiency of intellect, in comparison with ours, on the part of these our historical predecessors as to indicate so rapid a change of intelligence as would, if we were able to carry our comparison back for another similar period, inevitably land us among a lot of savages similar to those who fringe the civilization of the present period. Intellectually measured, the civilized men of eight or ten thousand years ago must, I think, have been but little inferior to ourselves, and we should have to peer very far back indeed before we reached a status or condition in which the highest type of humanity was the congener of the cave lion, disputing with him a miserable existence, shielded only from the elements by an overhanging rock, or the fortuitous discovery of some convenient cavern.

If this be so, we are forced back again to the consideration of the questions with which this section opened; where are the evidences of man’s early intellectual superiority? are they limited to those deduced from the discovery of certain stone implements of the early rude, and later polished ages? and, if so, can we offer any feasible explanation either of their non-existence or disappearance?

In the first place, it may be considered as admitted by archæologists that no exact line can be drawn between the later of the two stone-weapon epochs, the polished Neolithic stone epoch, and the succeeding age of bronze. They are agreed that these overlap each other, and that the rude hunters, who contented themselves with stone implements of war and the chase, were coeval with people existing in other places, acquainted with the metallurgical art, and therefore of a high order of intelligence. The former are, in fact, brought within the limit of historic times.

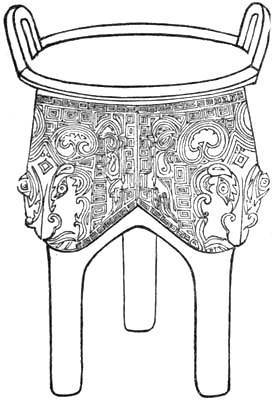

Fig. 25. – Incense Burner(?).Chen Dynasty, B.C. 1122 to B.C. 255.

(From the Poh Ku T’u.)

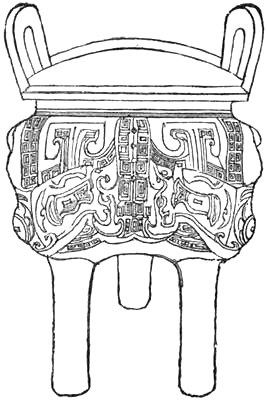

Fig. 26. – Tripod of the Shang Dynasty.

Probable date, B.C. 1649.

(From the Poh Ku T’u.)

Fig. 27. – Tripod of Fu Yih,Shang Dynasty.

(From the Poh Ku T’u.)

Fig. 28. – Tripod of Kwai Wan,Chen Dynasty, B.C. 1122 to B.C. 255

(From the Poh Ku T’u.)

A similar inference might not unfairly be drawn with regard to those numerous discoveries of proofs of the existence of ruder man, at still earlier periods. The flint-headed arrow of the North American Indian, and the stone hatchet of the Australian black-fellow exist to the present day; and but a century or two back, would have been the sole representatives of the constructive intelligence of humanity over nearly one half the inhabited surface of the world. No philosopher, with these alone to reason on, could have imagined the settled existence, busy industry, and superior intelligence which animated the other half; and a parallel suggestive argument may be supported by the discovery of human relics, implements, and artistic delineations such as those of the hairy mammoth or the cave-bear. These may possibly be the traces of an outlying savage who co-existed with a far more highly-organized people elsewhere,88 just as at the present day the Esquimaux, who are by some geologists considered as the descendants of Palæolithic man, co-exist with ourselves. They, like their reputed ancestors, have great ability in carving on bone, &c.; and as an example of their capacity not only to conceive in their own minds a correct notion of the relative bearings of localities, but also to impart the idea lucidly to others, I annex a wood-cut of a chart drawn by them, impromptu, at the request of Sir J. Ross, who, inferentially, vouches for its accuracy.

Fig. 29. (From Sir John Ross’ Second Voyage to the Arctic Regions.)

There is but a little step between carving the figure of a mammoth or horse, and using them as symbols. Multiply them, and you have the early hieroglyphic written language of the Chinese and Egyptians. It is not an unfair presumption that at no great distance, in time or space, either some generations later among his own descendants, or so many nations’ distance among his coevals, the initiative faculty of the Palæolithic savage was usefully applied to the communication of ideas, just as at a much later date the Kououen symbolic language was developed or made use of among the early Chinese.89