полная версия

полная версияMythical Monsters

The introduction of the Dingo, by the Australian blacks in their southward migration, is supposed to have caused the extinction of the Thylacinus (T. cynocephalus), or striped Australian wolf, on the main land of Australia, where it was once abundant; it is now only to be found in the remote portions of the island of Tasmania. This destruction of one species by another is paralleled in our own country by the approaching extinction of the indigenous and now very rare black rat, which has been almost entirely displaced by the fierce grey rat from Norway.

We learn from incidental passages in the Bamboo Books60 that the rhinoceros, which is now unknown in China, formerly extended throughout that country. We read of King Ch’aou, named Hĕa (B.C. 980), that “in his sixteenth year [of reign] the king attacked Ts’oo, and in crossing the river Han met with a large rhinoceros.” And, again, of King E, named Sëĕ (B.C. 860), that “in his sixth year, when hunting in the forest of Shay, he captured a rhinoceros and carried it home.” There is also mention made – though this is less conclusive – that in the time of King Yiu, named Yeu (B.C. 313), the King of Yueh sent Kung-sze Yu with a present of three hundred boats, five million arrows, together with rhinoceros’ horns and elephants’ teeth.

Elephants are now unknown in China except in a domesticated state, but they probably disputed its thick forest and jungly plains with the Miaotsz, Lolos, and other tribes which held the country before its present occupants. This may be inferred from the incidental references to them in the Shan Hai King, a work reputed to be of great antiquity, of which more mention will be made hereafter, and from evidence contained in other ancient Chinese works which has been summarized by Mr. Kingsmill61 as follows: —

“The rhinoceros and elephant certainly lived in Honan B.C. 600. The Tso-chuen, commenting on the C‘hun T‘siu of the second year of the Duke Siuen (B.C. 605), describes the former as being in sufficient abundance to supply skins for armour. The want, according to the popular saying, was not of rhinoceroses to supply skins, but of courage to animate the wearers. From the same authority (Duke Hi XIII., B.C. 636) we learn that while T‘soo (Hukwang) produced ivory and rhinoceros’ skins in abundance, Tsin, lying north of the Yellow River, on the most elevated part of the Loess, was dependent on the other for its supplies of those commodities. The Tribute of Yu tells the same tale. Yang-chow and King (Kiangpeh and Hukwang), we are told, sent tribute of ivory and rhinoceros’ hide, while Liang (Shensi) sent the skins of foxes and bears. Going back to mythical times, we find Mencius (III. ii. 9) telling how Chow Kung expelled from Lu (Shantung) the elephants and rhinoceroses, the tigers and leopards.”

Mr. Kingsmill even suggests that the species referred to were the mammoth and the Siberian rhinoceros (R. tichorhinus).

M. Chabas62 publishes an Egyptian inscription showing that the elephant existed in a feral state in the Euphrates Valley in the time of Thothmes III. (16th century B.C.). The inscription records a great hunting of elephants in the neighbourhood of Nineveh.

Tigers still abound in Manchuria and Corea, their skins forming a regular article of commerce in Vladivostock, Newchwang, and Seoul. They are said to attain larger dimensions in these northern latitudes than their southern congener, the better-known Bengal tiger. They are generally extinct in China Proper; but Père David states that he has seen them in the neighbourhood of Pekin, in Mongolia, and at Moupin, and they are reported to have been seen near Amoy. Within the last few years63 a large specimen was killed by Chinese soldiery within a few miles of the city of Ningpo; and it is probable that at no distant date they ranged over the whole country from Hindostan to Eastern Siberia, as they are incidentally referred to in various Chinese works – the Urh Yah specially recording the capture of a white tiger in the time of the Emperor Süen of the Han dynasty, and of a black one, in the fourth year of the reign of Yung Kia, in a netted surround in Kien Ping Fu in the district of Tsz Kwei.

The tailed deer or Mi-lu (Cervus Davidianus of Milne Edwardes), which Chinese literature64 indicates as having once been of common occurrence throughout China, is now only to be found in the Imperial hunting grounds south of Peking, where it is restricted to an enclosure of fifty miles in circumference. It is believed to exist no longer in a wild state, as no trace of it has been found in any of the recent explorations of Asia. The Ch‘un ts‘iu (B.C. 676) states that this species appeared in the winter of that year, in such numbers that it was chronicled in the records of Lu (Shantung), and that in the following autumn it was followed by an inroad of “Yih,” which Mr. Kingsmill believes to be the wolf.

There also appears reason to suppose that the ostrich had a much more extended range than at present; for we find references in the Shi-Ki,65 or book of history of Szema Tsien, to “large birds with eggs as big as water-jars” as inhabiting T‘iaou-chi, identified by Mr. Kingsmill as Sarangia or Drangia; and, in speaking of Parthia, it says, “On the return of the mission he sent envoys with it that they might see the extent and power of China. He sent with them, as presents to the Emperor, eggs of the great bird of the country, and a curiously deformed man from Samarkand.”

The gigantic Chelonians which once abounded in India and the Indian seas are now entirely extinct; but we have had little difficulty in believing the accounts of their actual and late existence contained in the works of Pliny and Ælian since the discovery of the Colossochelys, described by Dr. Falconer, in the Upper Miocene deposits of the Siwalik Hills in North-Western India. The shell of Colossochelys Atlas (Falconer and Cautley) measured twelve feet, and the whole animal nearly twenty.

Pliny,66 who published his work on Natural History about A.D. 77, states that the turtles of the Indian Sea are of such vast size that a single shell is sufficient to roof a habitable cottage, and that among the islands of the Red Sea the navigation is mostly carried on in boats formed from this shell.

Ælian,67 about the middle of the third century of our era, is more specific in his statement, and says that the Indian river-tortoise is very large, and in size not less than a boat of fair magnitude; also, in speaking of the Great Sea, in which is Taprobana (Ceylon), he says: “There are very large tortoises generated in this sea, the shell of which is large enough to make an entire roof; for a single one reaches the length of fifteen cubits, so that not a few people are able to live beneath it, and certainly secure themselves from the vehement rays of the sun; they make a broad shade, and so resist rain that they are preferable for this purpose to tiles, nor does the rain beating against them sound otherwise than if it were falling on tiles. Nor, indeed, do those who inhabit them have any necessity for repairing them, as in the case of broken tiles, for the whole roof is made out of a solid shell so that it has the appearance of a cavernous or undermined rock, and of a natural roof.”

El Edrisi, in his great geographical work,68 completed A.D. 1154, speaks of them as existing down to his day, but as his book is admitted to be a compilation from all preceding geographical works, he may have been simply quoting, without special acknowledgment, the statements given above. He says, speaking of the Sea of Herkend (the Indian Ocean west of Ceylon), “It contains turtles twenty cubits long, containing within them as many as one thousand eggs.” Large tortoises formerly inhabited the Mascarene islands, but have been destroyed on all of them, with the exception of the small uninhabited Aldabra islands, north of the Seychelle group; and those formerly abundant on the Galapagos islands are now represented by only a few survivors, and the species rapidly approaches extinction.

I shall close this chapter with a reference to a creature which, if it may not be entitled to be called “the dragon,” may at least be considered as first cousin to it. This is a lacertilian of large size, at least twenty feet in length, panoplied with the most horrifying armour, which roamed over the Australian continent during Pleistocene times, and probably until the introduction of the aborigines.

Its remains have been described by Professor Owen in several communications to the Royal Society,69 under the name of Megalania prisca. They were procured by Mr. G. F. Bennett from the drift-beds of King’s Creek, a tributary of the Condamine River in Australia. It was associated with correspondingly large marsupial mammals, now also extinct.

From the portions transmitted to him Professor Owen determined that it presented in some respects a magnified resemblance of the miniature existing lizard, Moloch horridus, found in Western Australia,70 of which Dr. Gray remarks, “The external appearance of this lizard is the most ferocious of any that I know.” In Megalania the head was rendered horrible and menacing by horns projecting from its sides, and from the tip of the nose, which would be “as available against the attacks of Thylacoleo as the buffalo’s horns are against those of the South African lion.” The tail consisted of a series of annular segments armed with horny spikes, represented by the less perfectly developed ones in the existing species Uromastix princeps from Zanzibar, or in the above-mentioned moloch. In regard to these the Professor says, “That the horny sheaths of the above-described supports or cores arming the end of the tail may have been applied to deliver blows upon an assailant, seems not improbable, and this part of the organization of the great extinct Australian dragon may be regarded, with the cranial horn, as parts of both an offensive and defensive apparatus.”

The gavial of the Ganges is reported to be a fish-eater only, and is considered harmless to man. The Indian museums, however, have large specimens, which are said to have been captured after they had destroyed several human beings; and so we may imagine that this structurally herbivorous lizard (the Megalania having a horny edentate upper jaw) may have occasionally varied his diet, and have proved an importunate neighbour to aboriginal encampments in which toothsome children abounded, and that it may, in fact, have been one of the sources from which the myth of the Bunyip, of which I shall speak hereafter, has been derived.

CHAPTER III.

ANTIQUITY OF MAN

I do not propose to bestow any large amount of space upon the enumeration of the palæontological evidence of the antiquity of man. The works of the various eminent authors who have devoted themselves to the special consideration of this subject exhaust all that can be said upon it with our present data, and to these I must refer the reader who is desirous of acquainting himself critically with its details, confining myself to a few general statements based on these labours.

In the early days of geological science when observers were few, great groups of strata were arranged under an artificial classification, which, while it has lost to a certain extent the specific value which it then assumed to possess, is still retained for purposes of convenient reference. Masters of the science acquired, so to say, a possessive interest in certain regions of it, and the names of Sedgwick, Murchison, Jukes, Phillips, Lyell, and others became, and will remain, inseparably associated with the history of those great divisions of the materials of the earth’s crust, which, under the names of the Cambrian, Silurian, Devonian, Carboniferous, and Tertiary formations, have become familiar to us.

In those days, when observations were limited to a comparatively small area, the lines separating most of these formations were supposed to be hard and definite; forms of life which characterized one, were presumed to have become entirely extinct before the inauguration of those which succeeded them, and breaks in the stratigraphical succession appeared to justify the opinion, held by a large and influential section, that great cataclysms or catastrophes had marked the time when one age or formation terminated and another commenced to succeed it.

By degrees, and with the increase of observers, both in England and in every portion of the world, modifications of these views obtained; passage beds were discovered, connecting by insensible gradations formations which had hitherto been supposed to present the most abrupt separations; transitional forms of life connecting them were unearthed; and an opinion was advanced, and steadily confirmed, which at the present day it is probable no one would be found to dispute, that not all in one place or country, but discoverable in some part or other of the world, a perfect sequence exists, from the very earliest formations of which we have any cognizance, up to the alluvial and marine deposits in process of formation at the present day.71

Correlatively it was deduced that the same phenomena of nature have been in action since the earliest period when organic existence can be affirmed. The gradual degradation of pre-existing continents by normal destructive agencies, the upheaval and subsidence of large areas, the effusion from volcanic vents, into the air or sea, of ashes and lavas, the action of frost and ice, of heat, rain, and sunshine – all these have acted in the past as they are still acting before our eyes.

In earlier days, arguing from limited data, a progressive creation was claimed which confined the appearance of the higher form of vertebrate life to a successive and widely-stepped gradation.

Hugh Miller, and other able thinkers, noted with satisfaction the appearance, first of fish, then of reptiles, next of birds and mammals, and finally, as the crowning work of all, both geologically and actually, quite recently of man.

This wonderful confirmation of the Biblical history of creation appealed so gratefully to many, that it caused for a time a disposition to cramp discovery, and even to warp the facts of science, in order to make them harmonize with the statements of Revelation. The alleged proofs of the existence of pre-historic man were for a long time jealously disputed, and it was only by slow degrees that they were admitted, that the tenets of the Darwinian school gained ground, and that the full meaning was appreciated of such anomalies as the existence at the present day of Ganoid fishes both in America and Europe, of true Palæozoic type, or of Oolitic forms on the Australian continent and in the adjacent seas.

But step by step marvellous palæontological discoveries were made, and the pillars which mark the advent of each great form of life have had to be set back, until now no one would, I think, be entirely safe in affirming that even in the Cambrian, the oldest of all fossiliferous formations, vestiges of mammals, that is to say, of the highest forms of life, may not at a future day be found, or that the records contained between the Cambrian and the present day, may not in fact be but a few pages as compared with the whole volume of the world’s history.72

It is with the later of these records that we have to deal, in which discoveries have been made sufficiently progressive to justify the expectation that they have by no means reached their limit, and sufficiently ample in themselves to open the widest fields for philosophic speculation and deduction.

Before stating these, it may be premised that estimates have been attempted by various geologists of the collective age of the different groups of formations.73 These are based on reasonings which for the most part it is unnecessary to give in detail, in so much as these can scarcely yet be considered to have passed the bounds of speculation, and very different results can be arrived at by theorists according to the relative importance which they attach to the data employed in the calculation.

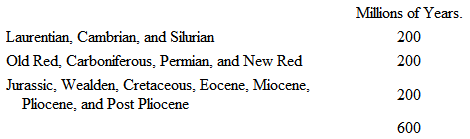

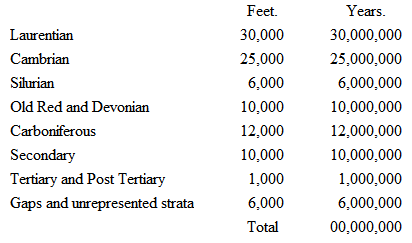

Thus Mr. T. Mellard Reade, in a paper communicated to the Royal Society in 1878, concludes that the formation of the sedimentary strata must have occupied at least six hundred million years: which he divides in round numbers as follows: —

He estimates the average thickness of the sedimentary crust of the earth to be at least one mile, and from a computation of the proportion of carbonate and sulphate of lime to materials held in suspension in various river-waters from a variety of formations, infers that one-tenth of this crust is calcareous.

He estimates the annual flow of water in all the great river-basins, the proportion of rain-water running off the granitic and trappean rocks, the percentage of lime in solution which they carry down, and arrives at the conclusion that the minimum time requisite for the elimination of the calcareous matter contained in the sedimentary crust of the earth, is at least six hundred millions of years.

A writer in the Gentleman’s Magazine74 (Professor Huxley?), whose article I am only able to quote at second-hand, makes an estimate which, though much lower than the above, is still of enormous magnitude, as follows: —

Mr. Darwin, arguing upon Sir W. Thompson’s estimate of a minimum of ninety-eight and maximum of two hundred millions of years since the consolidation of the crust, and on Mr. Croll’s estimate of sixty millions, as the time elapsed since the Cambrian period, considers that the latter is quite insufficient to permit of the many and great mutations of life which have certainly occurred since then. He judges from the small amount of organic change since the commencement of the glacial epoch, and adds that the previous one hundred and forty million years can hardly be considered as sufficient for the development of the varied forms of life which certainly existed towards the close of the Cambrian period.

On the other hand, Mr. Croll considers that it is utterly impossible that the existing order of things, as regards our globe, can date so far back as anything like five hundred millions of years, and, starting with referring the commencement of the Glacial epoch to two hundred and fifty thousand years ago, allows fifteen millions since the beginning of the Eocene period, and sixty millions of years in all since the beginning of the Cambrian period. He bases his arguments on the limit to the age of the sun’s heat as detailed by Sir William Thompson.

Sir Charles Lyell and Professor Haughton respectively estimated the expiration of time from the commencement of the Cambrian at two hundred and forty and two hundred millions of years, basing their calculations on the rate of modification of the species of mollusca, in the one case, and on the rate of formation of rocks and their maximum thickness, in the other.

This, moreover, is irrespective of the vast periods during which life must have existed, which on the development theory necessarily preceded the Cambrian, and, according to Mr. Darwin, should not be less than in the proportion of five to two.

In fine, one school of geologists and zoologists demand the maximum periods quoted above, to account for the amount of sedimentary deposit, and the specific developments which have occurred; the other considers the periods claimed as requisite for these actions to be unnecessary, and to be in excess of the limits which, according to their views, the physical elements of the case permit.

Mr. Wallace, in reviewing the question, dwells on the probability of the rate of geological changes having been greater in very remote times than it is at present, and thus opens a way to the reconciliation of the opposing views so far as one half the question is concerned.

Having thus adverted to the principles upon which various theorists have in part based their attacks on the problem of the estimation of the duration of geological ages, I may now make a few more detailed observations upon those later periods during which man is, now, generally admitted to have existed, and refer lightly to the earlier times which some, but not all, geologists consider to have furnished evidences of his presence.

I omit discussing the doubtful assertions of the extreme antiquity of man, which come to us from American observers, such as are based on supposed footprints in rocks of secondary age, figured in a semi-scientific and exceedingly valuable popular journal. There are other theories which I omit, both because they need further confirmation by scientific investigators, and because they deal with periods so remote as to be totally devoid of significance for the argument of this work.

Nor, up to the present time, are the evidences of the existence of man during Miocene and Pliocene times admitted as conclusive. Professor Capellini has discovered, in deposits recognised by Italian geologists as of Pliocene age, cetacean bones, which are marked with incisions such as only a sharp instrument could have produced, and which, in his opinion, must be ascribed to human agency. To this view it is objected that the incisions might have been made by the teeth of fishes, and further evidence is waited for.

Not a few discoveries have been made, apparently extending the existence of man to a much more remote antiquity, that of Miocene times. M. l’Abbé Bourgeois has collected, from undoubted Miocene strata at Thenay, supposed flint implements which he conceives to exhibit evidences of having been fashioned by man, as well as stones showing in some cases traces of the action of fire, and which he supposes to have been used as pot-boilers. M. Carlos Ribeiro has made similar discoveries of worked flints and quartzites in the Pliocene and Miocene of the Tagus; worked flint has been found in the Miocene of Aurillac (Auvergne) by M. Tardy, and a cut rib of Halitherium fossile, a Miocene species, by M. Delaunay at Pouancé.

Very divided opinions are entertained as to the interpretation of the supposed implements discovered by M. l’Abbé Bourgeois. M. Quatrefages, after a period of doubt, has espoused the view of their being of human origin, and of Miocene age. “Since then,” he says, “fresh specimens discovered have removed my last doubts. A small knife or scraper, among others, which shows a fine regular finish, can, in my opinion, only have been shaped by man. Nevertheless, I do not blame those of my colleagues who deny or still doubt. In such a matter there is no very great urgency, and, doubtless, the existence of Miocene man will be proved, as that of Glacial and Pliocene has been, by facts.” Mr. Geikie, from whose work —Prehistoric Europe– I have summarized the above statements, says, in reference to this question: “There is unquestionably much force in what M. Quatrefages says; nevertheless, most geologists will agree with him that the question of man’s Miocene age still remains to be demonstrated by unequivocal evidence. At present, all that we can safely say is, that man was probably living in Europe near the close of the Pliocene period, and that he was certainly an occupant of our continent during glacial and interglacial times.”

Professor Marsh considers that the evidence, as it stands to-day, although not conclusive, “seems to place the first appearance of man [in America] in the Pliocene, and that the best proofs of this are to be found on the Pacific coast.” He adds: “During several visits to that region many facts were brought to my knowledge which render this more than probable. Man, at this time, was a savage, and was doubtless forced by the great volcanic outbreaks to continue his migration. This was at first to the south, since mountain chains were barriers on the east,” and “he doubtless first came across Behring’s Straits.”

I have hitherto assumed a certain acquaintance, upon the part of the general reader, with the terms Eocene, Miocene, and Pliocene, happily invented by Sir Charles Lyell to designate three of the four great divisions of the Tertiary age. These, from their universal acceptation and constant use, have “become familiar in our mouths as household words.” But it will be well, before further elaborating points in the history of these groups, bearing upon our argument, to take into consideration their subdivisions, and the equivalent or contemporary deposits composing them in various countries. This can be most conveniently done by displaying these, in descending order, in a tabular form, which I accordingly annex below. This is the more desirable as there are few departments in geological science which have received more attention than this; or in which greater returns, in the shape of important and interesting discoveries relative to man’s existence, have been made.