полная версия

полная версияMythical Monsters

There are, indeed, not a few remarkable forms, as to the class position of which, whether they should be assigned to birds or reptiles, opinion was for a long time, and is in a few instances still, divided. It is, for example, only of late years that the fossil form Archæopteryx36 (Fig. 4, p. 19) from the Solenhofen slates, has been definitely relegated to the former, but arguments against this disposal of it have been based upon the beak or jaws being furnished with true teeth, and the feather of the tail attached to a series of vertebræ, instead of a single flattened one as in birds. It appears to have been entirely plumed, and to have had a moderate power of flight.

Fig. 6. – Sivatherium (restored), from the Upper Miocenedeposits of the Siwalik Hills. (After Figuier.)

On the other hand, the Ornithopterus is only provisionally classed with reptiles, while the connection between the two classes is drawn still closer by the copious discovery of the birds from the Cretaceous formations of America, for which we are indebted to Professor Marsh.

The Lepidosiren, also, is placed mid-way between reptiles and fishes. Professor Owen and other eminent physiologists consider it a fish; Professor Bischoff and others, an amphibian reptile. It has a two-fold apparatus for respiration, partly aquatic, consisting of gills, and partly aerial, of true lungs.

So far, then, as abnormality of type is concerned, we have here instances quite as remarkable as those presented by most of the strange monsters with the creation of which mythological fancy has been credited.

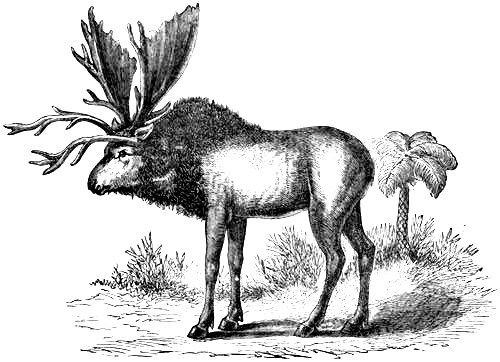

Fig. 7. – Skeleton of Megatherium. (After Figuier.)

Among mammals I shall only refer to the Megatherium, which appears to have been created to burrow in the earth and to feed upon the roots of trees and shrubs, for which purpose every organ of its heavy frame was adapted. This Hercules among animals was as large as an elephant or rhinoceros of the largest species, and might well, as it has existed until a late date, have originated the myths, current among the Indians of South America, of a gigantic tunnelling or burrowing creature, incapable of supporting the light of day.37

CHAPTER II.

EXTINCTION OF SPECIES

In reviewing the past succession of different forms of ancient life upon the globe, we are reminded of a series of dissolving views, in which each species evolves itself by an imperceptible gradation from some pre-existing one, arrives at its maximum of individuality, and then slowly fades away, while another type, either higher or lower, evolved in turn from it, emerges from obscurity, and succeeds it on the field of view.

Specific individuality has in all cases a natural term, dependent on physical causes, but that term is in many cases abruptly anticipated by a combination of unfavourable conditions.

Alteration of climate, isolation by geological changes, such as the submergence of continents and islands, and the competition of other species, are among the causes which have at all times operated towards its destruction; while, since the evolution of man, his agency, so far as we can judge by what we know of his later history, has been especially active in the same direction.

The limited distribution of many species, even when not enforced by insular conditions, is remarkable, and, of course, highly favourable to their destruction. A multiplicity of examples are familiar to naturalists, and possibly not a few may have attracted the attention of the ordinary observer.

For instance, it is probably generally known, that in our own island, the red grouse (which, by the way, is a species peculiar to Great Britain) is confined to certain moorlands, the ruffs and reeves to fen districts, and the nightingale,38 chough, and other species to a few counties; while Ireland is devoid of almost all the species of reptiles common to Great Britain. In the former cases, the need of or predilection for certain foods probably determines the favourite locality, and there are few countries which would not furnish similar examples. In the latter, the explanation depends on biological conditions dating prior to the separation of Ireland from the main continent. Among birds, it might fairly be presumed that the power of flight would produce unlimited territorial expansion, but in many instances the reverse is found to be the case: a remarkable example being afforded by the island of Tasmania, a portion of which is called the unsettled waste lands, or Western Country. This district, which comprises about one-third of the island upon the western side, and is mainly composed of mountain chains of granites, quartzite, and mica schists, is entirely devoid of the numerous species of garrulous and gay-plumaged birds, such as the Mynah mocking-bird, white cockatoo, wattle bird, and Rosella parrot, though these abundantly enliven the eastern districts, which are fertilized by rich soils due to the presence of ranges of basalt, greenstone, and other trappean rocks.

Another equally striking instance is given by my late father, Mr. J. Gould, in his work on the humming-birds. Of two species, inhabiting respectively the adjacent mountains of Pichincha and Chimborazo at certain elevations, each is strictly confined to its own mountain; and, if my memory serves me correctly, he mentions similar instances of species peculiar to different peaks of the Andes.

Limitation by insular isolation is intelligible, especially in the case of mammals and reptiles, and of birds possessing but small power of flight; and we are, therefore, not surprised to find Mr. Gosse indicating, among other examples, that even the smallest of the Antilles has each a fauna of its own, while the humming-birds, some of the parrots, cuckoos, and pigeons, and many of the smaller birds are peculiar to Jamaica. He states still further, that in the latter instance many of the animals are not distributed over the whole island, but confined to a single small district.

Continental limitation is effected by mountain barriers. Thus, according to Mr. Wallace, almost all the mammalia, birds, and insects on one side of the Andes and Rocky Mountains are distinct in species from those on the other; while a similar difference, but smaller in degree, exists with reference to regions adjacent to the Alps and Pyrenees.

Climate, broad rivers, seas, oceans, forests, and even large desert wastes, like the Sahara or the great desert of Gobi, also act more or less effectively as girdles which confine species within certain limits.

Dependence on each other or on supplies of appropriate food also form minor yet practical factors in the sum of limitation; and a curious example of the first is given by Dr. Van Lennep with reference to the small migratory birds that are unable to perform the flight of three hundred and fifty miles across the Mediterranean. He states that these are carried across on the backs of cranes.39

In the autumn many flocks of cranes may be seen coming from the North, with the first cold blast from that quarter, flying low, and uttering a peculiar cry, as if of alarm, as they circle over the cultivated plains. Little birds of every species may be seen flying up to them, while the twittering cries of those already comfortably settled upon their backs may be distinctly heard. On their return in the spring they fly high, apparently considering that their little passengers can easily find their way down to the earth.

The question of food-supply is involved in the more extended subject of geological structure, as controlling the flora and the insect life dependent on it. As an example we may cite the disappearance of the capercailzie from Denmark with the decay of the pine forests abundant during late Tertiary periods.

Collision, direct or indirect, with inimical species often has a fatal ending. Thus the dodo was exterminated by the swine which the early visitors introduced to the Mauritius and permitted to run wild there; while the indigenous insects, mollusca, and perhaps some of the birds of St. Helena, disappeared as soon as the introduction of goats caused the destruction of the whole flora of forest trees.

The Tsetse fly extirpates all horses, dogs, and cattle, from certain districts of South Africa, and a representative species in Paraguay is equally fatal to new-born cattle and horses.

Mr. Darwin40 shows that the struggle is more severe between species of the same genus, when they come into competition with each other, than between species of distinct genera. Thus one species of swallow has recently expelled another from part of the United States; and the missel-thrush has driven the song-thrush from part of Scotland. In Australia the imported hive-bee is rapidly exterminating the small stingless native bee, and similar cases might be found in any number.

Mr. Wallace, in quoting Mr. Darwin as to these facts, points the conclusion that “any slight change, therefore, of physical geography or of climate, which allows allied species hitherto inhabiting distinct areas to come into contact, will often lead to the extermination of one of them.”

It is the province of the palæontologist to enumerate the many remarkable forms which have passed away since man’s first appearance upon the globe, and to trace their fluctuations over both hemispheres as determined by the advance and retreat of glacial conditions, and by the protean forms assumed by past and existing continents under oscillations of elevation and depression. Many interesting points, such as the dates of the successive separation of Ireland and Great Britain from the main continent, can be determined with accuracy from the record furnished by the fossil remains of animals of those times; and many interesting associations of animals with man at various dates, in our present island home and in other countries, have been traced by the discovery of their remains in connection with his, in bone deposits in caverns and elsewhere.

Conversely, most valuable deductions are drawn by the zoologist from the review which he is enabled to take, through the connected labours of his colleagues in all departments, of the distinct life regions now mapped out upon the face of the globe. These, after the application of the necessary corrections for various disturbing or controlling influences referred to above, afford proof reaching far back into past periods, of successive alterations in the disposition of continents and oceans, and of connections long since obliterated between distant lands.

The palæontologist reasons from the past to the present, the zoologist from the present to the past; and their mutual labours explain the evolution of existing forms, and the causes of the disparity or connection between those at present characterizing the different portions of the surface of the globe.

The palæontologist, for example, traces the descent of the horse, which, until its reintroduction by the Spaniards was unknown in the New World, through a variety of intermediate forms, to the genus Orohippus occurring in Eocene deposits in Utah and Wyoming. This animal was no larger than a fox, and possessed four separated toes in front, and three behind. Domestic cattle he refers to the Bos primigenius, and many existing Carnivora to Tertiary forms such as the cave-bear, cave-lion, sabre-tiger, and the like.

The zoologist groups the existing fauna into distinct provinces, and demands, in explanation of the anomalies which these exhibit, the reconstruction of large areas, of which only small outlying districts remain at the present date, in many instances widely separated by oceans, though once forming parts of the same continent; and so, for the simile readily suggests itself, the workers in another branch of science, Philology, argue from words and roots scattered like fossils through the various dialects of very distant countries, a mutual descent from a common Aryan language: the language of a race of which no historical record exists, though in regard to its habits, customs, and distribution much may be affirmed from the large collection of word specimens stored in philological museums.

Thus Mr. Sclater, on zoological grounds, claims the late existence of a continent which he calls Lemuria, extending from Madagascar to Ceylon and Sumatra; and for similar reasons Mr. Wallace extends the Australia of Tertiary periods to New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, and perhaps to Fiji, and from its marsupial types infers a connection with the northern continent during the Secondary period.

Again, the connection of Europe with North Africa during a late geological period is inferred by many zoologists from the number of identical species of mammalia inhabiting the opposite sides of the Mediterranean, and palæontologists confirm this by the discovery of the remains of elephants in cave-deposits in Malta, and of hippopotami in Gibraltar; while hydrographers furnish the supplemental suggestive evidence that an elevation of only fifteen hundred feet would be sufficient to establish two broad connections between the two continents – so as to unite Italy with Tripoli and Spain with Morocco, and to convert the Mediterranean Sea into two great lakes, which appears, in fact, to have been its condition during the Pliocene and Post Pliocene periods.

It was by means of these causeways that the large pachyderms entered Britain, then united to the continent; and it was over them they retreated when driven back by glacial conditions, their migration northward being effectually prevented by the destruction of the connecting arms of land.

Some difference of opinion exists among naturalists as to the extent to which zoological regions should be subdivided, and as to their respective limitations.

But Mr. A. R. Wallace, who has most recently written on the subject, is of opinion that the original division proposed by Mr. Sclater in 1857 is the most tenable, and he therefore adopts it in the very exhaustive work upon the geographical distribution of animals which he has recently issued. Mr. Sclater’s Six Regions are as follows: —

1. —The Palæarctic Region, including Europe, Temperate Asia, and North Africa to the Atlas mountains.

2. —The Ethiopian Region, Africa south of the Atlas, Madagascar, and the Mascarene islands, with Southern Arabia.

3. —The Indian Region, including India south of the Himalayas, to South China, and to Borneo and Java.

4. —The Australian Region, including Celebes and Lombok, Eastward to Australia and the Pacific islands.

5. —The Nearctic Region, including Greenland, and North America, to Northern Mexico.

6. —The Neotropical Region, including South America, the Antilles, and Southern Mexico.

This arrangement is based upon a detailed examination of the chief genera and families of birds, and also very nearly represents the distribution of mammals and of reptiles. Its regions are not, as in other subsequently proposed and more artificial systems, controlled by climate; for they range, in some instances, from the pole to the tropics. It probably approaches more nearly than any other yet proposed to that desideratum, a division of the earth into regions, founded on a collation of the groups of forms indigenous to or typical of them, and upon a selection of those peculiar to them; with a disregard of, or only admitting with caution, any which, though common to and apparently establishing connection between two or more regions, may have in fact but little value for the purpose of such comparison; from the fact of its being possible to account for their extended range by their capability of easy transport from one region to another by common natural agencies.41

Such an arrangement should be consistent with the retrospective information afforded by palæontology; and, taking an extended view of the subject, be not merely a catalogue of the present, but also an index of the past. It should afford an illustration of an existing phase of the distribution of animal life, considered as the last of a long series of similar phases which have successively resulted from changes in the disposition of land and water, and from other controlling agencies, throughout all time. A reconstruction of the areas respectively occupied by the sea and the land at different geological periods will be possible, or at least greatly facilitated, when a complete system of similar groupings, illustrative of each successive period, has been compiled.

It is obvious that any great cosmical change, affecting to a wide extent any of the regions, might determine a destruction of specific existence; and this on a large scale, in comparison with the change which is always progressing in a smaller degree in the different and isolated divisions.

The brief remarks which I have made on this subject are intended to suggest, rather than to demonstrate – which could only be done by a lengthy series of examples – the causes influencing specific existence and its in many cases extreme frailty of tenure. And I shall now conclude by citing from the works of Lyell and Wallace a short list of notable species, now extinct, whose remains have been collected from late Tertiary, and Post Tertiary deposits – that is to say, at a time subsequent to the appearance of man. From other authors I have extracted an enumeration of species which have become locally or entirely extinct within the historic period.

These instances will, I think, be sufficient to show that, as similar destructive causes must have been in action during pre-historic times, it is probable that, besides those remarkable animals of which remains have been discovered, many others which then existed may have perished without leaving any trace of their existence. There is, consequently, a possibility that some at least of the so-called myths respecting extraordinary creatures, hitherto considered fabulous, may merely be distorted accounts —traditions– of species as yet unrecognised by Science, which have actually existed, and that not remotely, as man’s congener.

Extinct Post Tertiary MammaliaThe Mammoth. – Among other remarkable forms whose remains have been discovered in those later deposits, in which geologists are generally agreed that remains of man or traces of his handicraft have also been recognised, there is one which stands out prominently both for its magnitude and extensive range in time and space. Although the animal itself is now entirely extinct, delineations by the hand of Palæolithic man have been preserved, and even frozen carcases, with the flesh uncorrupted and fit for food, have been occasionally discovered.

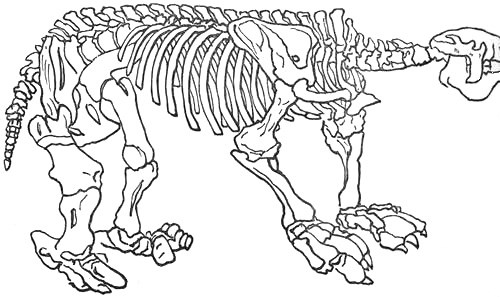

Fig. 9. – The Mammoth. (After Jukes.)

This is the mammoth, the Elephas primigenius of Blumenbach, a gigantic elephant nearly a third taller than the largest modern species, and twice its weight. Its body was protected from the severity of the semi-arctic conditions under which it flourished by a dense covering of reddish wool, and long black hair, and its head was armed or ornamented with tusks exceeding twelve feet in length, and curiously curved into three parts of a circle. Its ivory has long been, and still is, a valuable article of commerce, more especially in North-eastern Asia, and in Eschscholtz Bay in North America, near Behring’s straits, where entire skeletons are occasionally discovered, and where even the nature of its food has been ascertained from the undigested contents of its stomach.

There is a well-known case recorded of a specimen found (1799), frozen and encased in ice, at the mouth of the Lena. It was sixteen feet long, and the flesh was so well preserved that the Yakuts used it as food for their dogs. But similar instances occurred previously, for we find the illustrious savant and Emperor Kang Hi [A.D. 1662 to 1723] penning the following note42 upon what could only have been this species: —

“The cold is extreme, and nearly continuous on the coasts of the northern sea beyond Tai-Tong-Kiang. It is on this coast that the animal called Fen Chou is found, the form of which resembles that of a rat, but which equals an elephant in size. It lives in obscure caverns, and flies from the light. There is obtained from it an ivory as white as that of the elephant, but easier to work, and which will not split. Its flesh is very cold and excellent for refreshing the blood. The ancient work Chin-y-king speaks of this animal in these terms: ‘There is in the depths of the north a rat which weighs as much as a thousand pounds; its flesh is very good for those who are heated.’ The Tsée-Chou calls it Tai-Chou and speaks of another species which is not so large. It says that this is as big as a buffalo, buries itself like a mole, flies the light, and remains nearly always under ground; it is said that it would die if it saw the light of the sun or even that of the moon.”

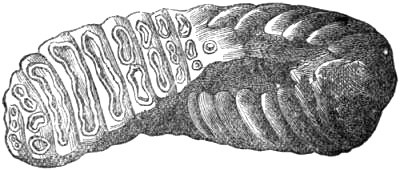

Fig. 10. – Tooth of the Mammoth. (After Figuier.)

It seems probable that discoveries of mammoth tusks formed in part the basis for the story which Pliny tells in reference to fossil ivory. He says43: – “These animals [elephants] are well aware that the only spoil that we are anxious to procure of them is the part which forms their weapon of defence, by Juba called their horns, but by Herodotus, a much older writer, as well as by general usage, and more appropriately, their teeth. Hence it is that, when these tusks have fallen off, either from accident or old age, they bury them in the earth.”

Nordenskjöld44 states that the savages with whom he came in contact frequently offered to him very fine mammoth tusks, and tools made of mammoth ivory. He computes that since the conquest of Siberia, useful tusks from more than twenty thousand animals have been collected.

Mr. Boyd Dawkins,45 in a very exhaustive memoir on this animal, quotes an interesting notice of its fossil ivory having been brought for sale to Khiva. He derives46 this account from an Arabian traveller, Abou-el-Cassim, who lived in the middle of the tenth century.

Figuier47 says: “New Siberia and the Isle of Lachon are for the most part only an agglomeration of sand, of ice, and of elephants’ teeth. At every tempest the sea casts ashore new quantities of mammoth’s tusks, and the inhabitants of New Siberia carry on a profitable commerce in this fossil ivory. Every year during the summer innumerable fishermen’s barks direct their course to this isle of bones, and during winter immense caravans take the same route, all the convoys drawn by dogs, returning charged with the tusks of the mammoth, weighing each from one hundred and fifty to two hundred pounds. The fossil ivory thus withdrawn from the frozen north is imported into China and Europe.”

In addition to its elimination by the thawing of the frozen grounds of the north, remains of the mammoth are procured from bogs, alluvial deposits, and from the destruction of submarine beds.48 They are also found in cave deposits, associated with the remains of other mammals, and with flint implements. This creature appears to have been an object of the chase with Palæolithic man.

Mr. Dawkins, reviewing all the discoveries, considers that its range, at various periods, extended over the whole of Northern Europe, and as far south as Spain; over Northern Asia, and North America down to the Isthmus of Darien. Dr. Falconer believes it to have had an elastic constitution, which enabled it to adapt itself to great change of climate.

Murchison, De Verneuil, and Keyserling believed that this species, as well as the woolly rhinoceros, belonged to the Tertiary fauna of Northern Asia, though not appearing until the Quaternary period in Europe.

Mr. Dawkins shows it to have been pre-glacial, glacial, and post-glacial in Britain and in Europe, and, from its relation to the intermediate species Elephas armeniacus, accepts it as the ancestor of the existing Indian elephant. Its disappearance was rapid, but not in the opinion of most geologists cataclysmic, as suggested by Mr. Howorth.

Another widely distributed species was the Rhinoceros tichorhinus– the smooth-skinned rhinoceros – also called the woolly rhinoceros and the Siberian rhinoceros, which had two horns, and, like the mammoth, was covered with woolly hair. It attained a great size; a specimen, the carcase of which was found by Pallas imbedded in frozen soil near Wilui, in Siberia (1772), was eleven and a half feet in length. Its horns are considered by some of the native tribes of northern Asia to have been the talons of gigantic birds; and Ermann and Middendorf suppose that their discovery may have originated the accounts by Herodotus of the gold-bearing griffons and the arimaspi.