полная версия

полная версияThe Bābur-nāma

Shāh Beg’s requests for intervention began in 926 AH. (1520 AD.), as also did the remonstrance of the Persian officers with Bābur; his couriers followed one another with entreaty that the Amīrs would contrive for Bābur to retire, with promise of obeisance and of yearly tribute. The Amīrs set forth to Bābur that though Shāh Shujā‘ Beg had offended and had been deserving of wrath and chastisement, yet, as he was penitent and had promised loyalty and tribute, it was now proper for Bābur to raise the siege (of 926 AH.) and go back to Kābul. To this Bābur answered that Shāh Beg’s promise was a vain thing, on which no reliance could be placed; please God!, said he, he himself would take Qandahār and send Shāh Beg a prisoner to Harāt; and that he should be ready then to give the keys of the town and the possession of the Garm-sīr to any-one appointed to receive them.

This correspondence suits an assumption that Bābur acted for Shāh Ismā‘īl, a diplomatic assumption merely, the verbal veil, on one side, for anxiety lest Bābur or those with him should attack Harāt, – on the other, for Bābur’s resolve to hold Qandahār himself.

Amīr Khān was not satisfied with Bābur’s answer, but had his attention distracted by another matter, presumably ‘Ubaidu’l-lāh Khān’s attack on Harāt in the spring of the year (March-April 1521 AD.). Negociations appear to have been resumed later, since Khwānd-amīr claims it as their result that Bābur left Qandahār this year.

e. The Tārīkh-i-sind account.

Mīr Ma‘ṣūm is very brief; he says that in this year (his 922 AH.), Bābur went down to Qandahār before the year’s tribute in grain had been collected, destroyed the standing crops, encompassed the town, and reduced it to extremity; that Shāh Beg, wearied under reiterated attack and pre-occupied by operations in Sind, proposed terms, and that these were made with stipulation for the town to be his during one year more and then to be given over to Bābur. These terms settled, Bābur went to Kābul, Shāh Beg to Sīwī.

The Arghūn families were removed to Shāl and Sīwī, so that the year’s delay may have been an accommodation allowed for this purpose.

f. Concerning dates.

There is much discrepancy between the dates of the two historians. Khwānd-amīr’s agree with the few fixed ones of the period and with the course of events; several of Ma‘ṣūm’s, on the contrary, are seriatim five (lunar) years earlier. For instance, events Khwānd-amīr places under 927 AH. Ma‘ṣūm places under 922 AH. Again, while Ma‘ṣūm correctly gives 913 AH. (1507 AD.) as the year of Bābur’s first capture of Qandahār, he sets up a discrepant series later, from the success Shāh Beg had at Kāhān; this he allots to 921 AH. (1515 AD.) whereas Bābur received news of it (f. 233b) in the beginning of 925 AH. (1519 AD.). Again, Ma‘ṣūm makes Shāh Ḥasan go to Bābur in 921 AH. and stay two years; but Ḥasan spent the whole of 925 AH. with Bābur and is not mentioned as having left before the second month of 926 AH. Again, Ma‘ṣūm makes Shāh Beg surrender the keys of Qandahār in 923 AH. (1517 AD.), but 928 AH. (1522 AD.) is shewn by Khwānd-amīr’s dates and narrative, and is inscribed at Chihil-zīna.1547

928 AH. – DEC. 1st 1521 to NOV. 20th 1522 AD

a. Bābur visits Badakhshān.

Either early in this year or late in the previous one, Bābur and Māhīm went to visit Humāyūn in his government, probably to Faizābād, and stayed with him what Gul-badan calls a few days.

b. Expedition to Qandahār.

This year saw the end of the duel for possession of Qandahār. Khwānd-amīr’s account of its surrender differs widely from Ma‘ṣūm’s. It claims that Bābur’s retirement in 927 AH. was due to the remonstrances from Harāt, and that Shāh Beg, worn out by the siege, relied on the arrangement the Amīrs had made with Bābur and went to Sīwī, leaving one ‘Abdu’l-bāqī in charge of the place. This man, says Khwānd-amīr, drew the line of obliteration over his duty to his master, sent to Bābur, brought him down to Qandahār, and gave him the keys of the town – by the hand of Khwānd-amīr’s nephew Ghiyās̤u’d-dīn, specifies the Tarkhān-nāma. In this year messengers had come and gone between Bābur and Harāt; two men employed by Amīr Khān are mentioned by name; of them the last had not returned to Harāt when a courier of Bābur’s, bringing a tributary gift, announced there that the town was in his master’s hands. Khwānd-amīr thus fixes the year 928 AH. as that in which the town passed into Bābur’s hands; this date is confirmed by the one inscribed in the monument of victory at Chihil-zīna which Bābur ordered excavated on the naze of the limestone ridge behind the town. The date there given is Shawwāl 13th 928 AH. (Sep. 6th 1522 AD.).

Ma‘ṣūm’s account, dated 923 AH. (1517 AD.), is of the briefest: – Shāh Beg fulfilled his promise, much to Bābur’s approval, by sending him the keys of the town and royal residence.

Although Khwānd-amīr’s account has good claim to be accepted, it must be admitted that several circumstances can be taken to show that Shāh Beg had abandoned Qandahār, e. g. the removal of the families after Bābur’s retirement last year, and his own absence in a remote part of Sind this year.

c. The year of Shāh Beg’s death.

Of several variant years assigned for the death of Shāh Beg in the sources, two only need consideration.1548 There is consensus of opinion about the month and close agreement about the day, Sha‘bān 22nd or 23rd. Ma‘ṣūm gives a chronogram, Shahr-Sha‘bān, (month of Sha‘bān) which yields 928, but he does not mention where he obtained it, nor does anything in his narrative shew what has fixed the day of the month.

Two objections to 928 are patent: (1) the doubt engendered by Ma‘ṣūm’s earlier ante-dating; (2) that if 928 be right, Shāh Beg was already dead over two months when Qandahār was surrendered. This he might have been according to Khwānd-amīr’s narrative, but if he died on Sha‘bān 22nd 928 (July 26th 1522), there was time for the news to have reached Qandahār, and to have gone on to Harāt before the surrender. Shāh Beg’s death at that time could not have failed to be associated in Khwānd-amīr’s narrative with the fate of Qandahār; it might have pleaded some excuse with him for ‘Abdu’l-bāqī, who might even have had orders from Shāh Ḥasan to make the town over to Bābur whose suzerainty he had acknowledged at once on succession by reading the khut̤ba in his name. Khwānd-amīr however does not mention what would have been a salient point in the events of the siege; his silence cannot but weigh against the 928 AH.

The year 930 AH. is given by Niz̤āmu’d-dīn Aḥmad’s T̤abaqāt-i-akbarī (lith. ed. p. 637), and this year has been adopted by Erskine, Beale, and Ney Elias, perhaps by others. Some light on the matter may be obtained incidentally as the sources are examined for a complete history of India, perhaps coming from the affairs of Multān, which was attacked by Shāh Ḥasan after communication with Bābur.

d. Bābur’s literary work in 928 AH. and earlier.

1. The Mubīn. This year, as is known from a chronogram within the work, Bābur wrote the Turkī poem of 2000 lines to which Abū’l-faẓl and Badāyūnī give the name Mubīn (The Exposition), but of which the true title is said by the Nafā’isu’l-ma‘āsir to be Dar fiqa mubaiyan (The Law expounded). Sprenger found it called also Fiqa-i-bāburī (Bābur’s Law). It is a versified and highly orthodox treatise on Muḥammadan Law, written for the instruction of Kāmrān. A Commentary on it, called also Mubīn, was written by Shaikh Zain. Bābur quotes from it (f. 351b) when writing of linear measures. Berézine found and published a large portion of it as part of his Chrestomathie Turque (Kazan 1857); the same fragment may be what was published by Ilminsky. Teufel remarks that the MS. used by Berézine may have descended direct from one sent by Bābur to a distinguished legist of Transoxiana, because the last words of Berézine’s imprint are Bābur’s Begleitschreiben (envoi); he adds the expectation that the legist’s name might be learned. Perhaps this recipient was the Khwāja Kalān, son of Khwāja Yaḥya, a Samarkandī to whom Bābur sent a copy of his Memoirs on March 7th 1520 (935 AH. f. 363).1549

2. The Bābur-nāma diary of 925-6 AH. (1519-20 AD.). This is almost contemporary with the Mubīn and is the earliest part of the Bābur-nāma writings now known. It was written about a decade earlier than the narrative of 899 to 914 AH. (1494 to 1507 AD.), carries later annotations, and has now the character of a draft awaiting revision.

3. A Dīwān (Collection of poems). By dovetailing a few fragments of information, it becomes clear that by 925 AH. (1519 AD.) Bābur had made a Collection of poetical compositions distinct from the Rāmpūr Dīwān; it is what he sent to Pūlād Sult̤an in 925 AH. (f. 238). Its date excludes the greater part of the Rāmpūr one. It may have contained those verses to which my husband drew attention in the Asiatic Quarterly Review of 1911, as quoted in the Abūshqa; and it may have contained, in agreement with its earlier date, the verses Bābur quotes as written in his earlier years. None of the quatrains found in the Abūshqa and there attributed to “Bābur Mīrzā”, are in the Rāmpūr Dīwān; nor are several of those early ones of the Bābur-nāma. So that the Dīwān sent to Pūlād Sult̤ān may be the source from which the Abūshqa drew its examples.

On first examining these verses, doubt arose as to whether they were really by Bābur Mīrānshāhī; or whether they were by “Bābur Mīrzā” Shāhrukhī. Fortunately my husband lighted on one of them quoted in the Sanglakh and there attributed to Bābur Pādshāh. The Abūshqa quatrains are used as examples in de Courteille’s Dictionary, but without an author’s name; they can be traced there through my husband’s articles.1550

929 AH. – NOV. 20th 1522 to NOV. 10th 1523 AD

a. Affairs of Hindūstān.

The centre of interest in Bābur’s affairs now moves from Qandahār to a Hindūstān torn by faction, of which faction one result was an appeal made at this time to Bābur by Daulat Khān Lūdī (Yūsuf-khail) and ‘Alāu’d-dīn ‘Ālam Khān Lūdī for help against Ibrāhīm.1551

The following details are taken mostly from Aḥmad Yādgār’s Tārīkh-i-salāt̤īn-i-afāghana1552: – Daulat Khān had been summoned to Ibrāhīm’s presence; he had been afraid to go and had sent his son Dilāwar in his place; his disobedience angering Ibrāhīm, Dilāwar had a bad reception and was shewn a ghastly exhibit of disobedient commanders. Fearing a like fate for himself, he made escape and hastened to report matters to his father in Lāhor. His information strengthening Daulat Khān’s previous apprehensions, decided the latter to proffer allegiance to Bābur and to ask his help against Ibrāhīm. Apparently ‘Ālam Khān’s interests were a part of this request. Accordingly Dilāwar (or Apāq) Khān went to Kābul, charged with his father’s message, and with intent to make known to Bābur Ibrāhīm’s evil disposition, his cruelty and tyranny, with their fruit of discontent amongst his Commanders and soldiery.

b. Reception of Dilāwar Khān in Kābul.

Wedding festivities were in progress1553 when Dilāwar Khān reached Kābul. He presented himself, at the Chār-bāgh may be inferred, and had word taken to Bābur that an Afghān was at his Gate with a petition. When admitted, he demeaned himself as a suppliant and proceeded to set forth the distress of Hindūstān. Bābur asked why he, whose family had so long eaten the salt of the Lūdīs, had so suddenly deserted them for himself. Dilāwar answered that his family through 40 years had upheld the Lūdī throne, but that Ibrāhīm maltreated Sikandar’s amīrs, had killed 25 of them without cause, some by hanging some burned alive, and that there was no hope of safety in him. Therefore, he said, he had been sent by many amīrs to Bābur whom they were ready to obey and for whose coming they were on the anxious watch.

c. Bābur asks a sign.

At the dawn of the day following the feast, Bābur prayed in the garden for a sign of victory in Hindūstān, asking that it should be a gift to himself of mango or betel, fruits of that land. It so happened that Daulat Khān had sent him, as a present, half-ripened mangoes preserved in honey; when these were set before him, he accepted them as the sign, and from that time forth, says the chronicler, made preparation for a move on Hindūstān.

d. ‘Ālam Khān.

Although ‘Ālam Khān seems to have had some amount of support for his attempt against his nephew, events show he had none valid for his purpose. That he had not Daulat Khān’s, later occurrences make clear. Moreover he seems not to have been a man to win adherence or to be accepted as a trustworthy and sensible leader.1554 Dates are uncertain in the absence of Bābur’s narrative, but it may have been in this year that ‘Ālam Khān went in person to Kābul and there was promised help against Ibrāhīm.

e. Birth of Gul-badan.

Either in this year or the next was born Dil-dār’s third daughter Gul-badan, the later author of an Humāyūn-nāma written at her nephew Akbar’s command in order to provide information for the Akbar-nāma.

930 AH. – NOV. 10th 1523 to OCT. 29th 1524 AD

a. Bābur’s fourth expedition to Hindūstān.

This expedition differs from all earlier ones by its co-operation with Afghān malcontents against Ibrāhīm Lūdī, and by having for its declared purpose direct attack on him through reinforcement of ‘Ālam Khān.

Exactly when the start from Kābul was made is not found stated; the route taken after fording the Indus, was by the sub-montane road through the Kakar country; the Jīhlam and Chīn-āb were crossed and a move was made to within 10 miles of Lāhor.

Lāhor was Daulat Khān’s head-quarters but he was not in it now; he had fled for refuge to a colony of Bilūchīs, perhaps towards Multān, on the approach against him of an army of Ibrāhīm’s under Bihār Khān Lūdī. A battle ensued between Bābur and Bihār Khān; the latter was defeated with great slaughter; Bābur’s troops followed his fugitive men into Lāhor, plundered the town and burned some of the bāzārs.

Four days were spent near Lāhor, then move south was made to Dībālpūr which was stormed, plundered and put to the sword. The date of this capture is known from an incidental remark of Bābur about chronograms (f. 325), to be mid-Rabī‘u’l-awwal 930 AH. (circa Jan. 22nd 1524 AD.).1555 From Dībālpūr a start was made for Sihrind but before this could be reached news arrived which dictated return to Lāhor.

b. The cause of return.

Daulat Khān’s action is the obvious cause of the retirement. He and his sons had not joined Bābur until the latter was at Dībālpūr; he was not restored to his former place in charge of the important Lāhor, but was given Jalandhar and Sult̤ānpūr, a town of his own foundation. This angered him extremely but he seems to have concealed his feelings for the time and to have given Bābur counsel as if he were content. His son Dilāwar, however, represented to Bābur that his father’s advice was treacherous; it concerned a move to Multān, from which place Daulat Khān may have come up to Dībālpūr and connected with which at this time, something is recorded of co-operation by Bābur and Shāh Ḥasan Arghūn. But the incident is not yet found clearly described by a source. Dilāwar Khān told Bābur that his father’s object was to divide and thus weaken the invading force, and as this would have been the result of taking Daulat Khān’s advice, Bābur arrested him and Apāq on suspicion of treacherous intent. They were soon released, and Sult̤ānpūr was given them, but they fled to the hills, there to await a chance to swoop on the Panj-āb. Daulat Khān’s hostility and his non-fulfilment of his engagement with Bābur placing danger in the rear of an eastward advance, the Panj-āb was garrisoned by Bābur’s own followers and he himself went back to Kābul.

It is evident from what followed that Daulat Khān commanded much strength in the Panj-āb; evident also that something counselled delay in the attack on Ibrāhīm, perhaps closer cohesion in favour of ‘Ālam Khān, certainly removal of the menace of Daulat Khān in the rear; there may have been news already of the approach of the Aūzbegs on Balkh which took Bābur next year across Hindū-kush.

c. The Panj-āb garrison.

The expedition had extended Bābur’s command considerably, notably by obtaining possession of Lāhor. He now posted in it Mīr ‘Abdu’l-‘azīz his Master of the Horse; in Dībālpūr he posted, with ‘Ālam Khān, Bābā Qashqa Mughūl; in Sīālkot, Khusrau Kūkūldāsh, in Kalanūr, Muḥammad ‘Alī Tājik.

d. Two deaths.

This year, on Rajab 19th (May 23rd) died Ismā‘īl Ṣafawī at the age of 38, broken by defeat from Sult̤ān Salīm of Rūm.1556 He was succeeded by his son T̤ahmāsp, a child of ten.

This year may be that of the death of Shāh Shujā‘ Arghūn,1557 on Sha‘bān 22nd (July 18th), the last grief of his burden being the death of his foster-brother Fāẓil concerning which, as well as Shāh Beg’s own death, Mīr Ma‘ṣūm’s account is worthy of full reproduction. Shāh Beg was succeeded in Sind by his son Ḥasan, who read the khut̤ba for Bābur and drew closer links with Bābur’s circle by marrying, either this year or the next, Khalīfa’s daughter Gul-barg, with whom betrothal had been made during Ḥasan’s visit to Bābur in Kābul. Moreover Khalīfa’s son Muḥibb-i-‘alī married Nāhīd the daughter of Qāsim Kūkūldāsh and Māh-chūchūk Arghūn (f. 214b). These alliances were made, says Ma‘ṣūm, to strengthen Ḥasan’s position at Bābur’s Court.

e. A garden detail.

In this year and presumably on his return from the Panj-āb, Bābur, as he himself chronicles (f. 132), had plantains (bananas) brought from Hindūstān for the Bāgh-i-wafā at Adīnapūr.

931 AH. – OCT. 29th 1524 to OCT. 18th 1525 AD

a. Daulat Khān.

Daulat Khān’s power in the Panj-āb is shewn by what he effected after dispossessed of Lāhor. On Bābur’s return to Kābul, he came down from the hills with a small body of his immediate followers, seized his son Dilāwar, took Sult̤ānpūr, gathered a large force and defeated ‘Ālam Khān in Dībālpūr. He detached 5000 men against Sīālkot but Bābur’s begs of Lāhor attacked and overcame them. Ibrāhīm sent an army to reconquer the Panj-āb; Daulat Khān, profiting by its dissensions and discontents, won over a part to himself and saw the rest break up.

b. ‘Ālam Khān.

From his reverse at Dībālpūr, ‘Ālam Khān fled straight to Kābul. The further help he asked was promised under the condition that while he should take Ibrāhīm’s place on the throne of Dihlī, Bābur in full suzerainty should hold Lāhor and all to the west of it. This arranged, ‘Ālam Khān was furnished with a body of troops, given a royal letter to the Lāhor begs ordering them to assist him, and started off, Bābur promising to follow swiftly.

‘Ālam Khān’s subsequent proceedings are told by Bābur in the annals of 932 AH. (1525 AD.) at the time he received details about them (f. 255b).

c. Bābur called to Balkh.

All we have yet found about this affair is what Bābur says in explanation of his failure to follow ‘Ālam Khān as promised (f. 256), namely, that he had to go to Balkh because all the Aūzbeg Sult̤āns and Khāns had laid siege to it. Light on the affair may come from some Persian or Aūzbeg chronicle; Bābur’s arrival raised the siege; and risk must have been removed, for Bābur returned to Kābul in time to set out for his fifth and last expedition to Hindūstān on the first day of the second month of next year (932 AH. 1525). A considerable body of troops was in Badakhshān with Humāyūn; their non-arrival next year delaying his father’s progress, brought blame on himself.

SECTION III. HINDŪSTĀN

932 AH. – OCT. 18th 1525 to OCT. 8th 1526 AD.1558

(a. Fifth expedition into Hindūstān.)

(Nov. 17th) On Friday the 1st of the month of Ṣafar at the date 932, the Sun being in the Sign of the Archer, we set out for Hindūstān, crossed the small rise of Yak-langa, and dismounted in the meadow to the west of the water of Dih-i-ya‘qūb.1559 ‘Abdu’l-malūk the armourer came into this camp; he had gone seven or eight months earlier as my envoy to Sult̤ān Sa‘īd Khān (in Kāshghar), and now brought one of the Khān’s men, styled Yāngī Beg (new beg) Kūkūldāsh who conveyed letters, and small presents, and verbal messages1560 from the Khānīms and the Khān.1561

(Nov. 18th to 21st) After staying two days in that camp for the convenience of the army,1562 we marched on, halted one night,1563 and next dismounted at Bādām-chashma. There we ate a confection (ma‘jūn).

(Nov. 22nd) On Wednesday (Ṣafar 6th), when we had dismounted at Bārīk-āb, the younger brethren of Nūr Beg – he himself remaining in Hindūstān – brought gold ashrafīs and tankas1564 to the value of 20,000 shāhrukhīs, sent from the Lāhor revenues by Khwāja Ḥusain. The greater part of these moneys was despatched by Mullā Aḥmad, one of the chief men of Balkh, for the benefit of Balkh.1565

(Nov. 24th) On Friday the 8th of the month (Ṣafar), after dismounting at Gandamak, I had a violent discharge;1566 by God’s mercy, it passed off easily.

(Nov. 25th) On Saturday we dismounted in the Bāgh-i-wafā. We delayed there a few days, waiting for Humāyūn and the army from that side.1567 More than once in this history the bounds and extent, charm and delight of that garden have been described; it is most beautifully placed; who sees it with the buyer’s eye will know the sort of place it is. During the short time we were there, most people drank on drinking-days1568 and took their morning; on non-drinking days there were parties for ma‘jūn.

I wrote harsh letters to Humāyūn, lecturing him severely because of his long delay beyond the time fixed for him to join me.1569

(Dec. 3rd) On Sunday the 17th of Ṣafar, after the morning had been taken, Humāyūn arrived. I spoke very severely to him at once. Khwāja Kalān also arrived to-day, coming up from Ghaznī. We marched in the evening of that same Sunday, and dismounted in a new garden between Sult̤ānpur and Khwāja Rustam.

(Dec. 6th) Marching on Wednesday (Ṣafar 20th), we got on a raft, and, drinking as we went reached Qūsh-guṃbaz,1570 there landed and joined the camp.

(Dec. 7th) Starting off the camp at dawn, we ourselves went on a raft, and there ate confection (ma‘jūn). Our encamping-ground was always Qīrīq-ārīq, but not a sign or trace of the camp could be seen when we got opposite it, nor any appearance of our horses. Thought I, “Garm-chashma (Hot-spring) is close by; they may have dismounted there.” So saying, we went on from Qīrīq-ārīq. By the time we reached Garm-chashma, the very day was late;1571 we did not stop there, but going on in its lateness (kīchīsī), had the raft tied up somewhere, and slept awhile.

(Dec. 8th) At day-break we landed at Yada-bīr where, as the day wore on, the army-folks began to come in. The camp must have been at Qīrīq-ārīq, but out of our sight.

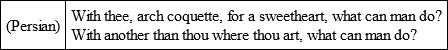

There were several verse-makers on the raft, such as Shaikh Abū’l-wajd,1572 Shaikh Zain, Mullā ‘Alī-jān, Tardī Beg Khāksār and others. In this company was quoted the following couplet of Muḥammad Ṣāliḥ: —1573

Said I, “Compose on these lines”;1574 whereupon those given to versifying, did so. As jokes were always being made at the expense of Mullā ‘Alī-jān, this couplet came off-hand into my head: —

Примечание 11575

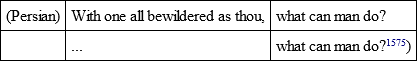

(b. Mention of the Mubīn.1576)

From time to time before it,1577 whatever came into my head, of good or bad, grave or jest, used to be strung into verse and written down, however empty and harsh the verse might be, but while I was composing the Mubīn, this thought pierced through my dull wits and made way into my troubled heart, “A pity it will be if the tongue which has treasure of utterances so lofty as these are, waste itself again on low words; sad will it be if again vile imaginings find way into the mind that has made exposition of these sublime realities.”1578 Since that time I had refrained from satirical and jesting verse; I was repentant (ta’īb); but these matters were totally out of mind and remembrance when I made that couplet (on Mullā ‘Alī-jān).1579 A few days later in Bīgrām when I had fever and discharge, followed by cough, and I began to spit blood each time I coughed, I knew whence my reproof came; I knew what act of mine had brought this affliction on me.