полная версия

полная версияThe Australian Army Medical Corps in Egypt

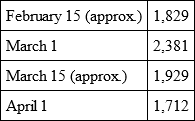

On March 1, 1,737 men were in hospital, 644 off duty and sick in the lines, or a total of 2,361.

On March 15, 1,429 were in hospital, 500 off duty and sick in the lines, or a total of 1,929.

On April 1, 1,217 were in hospital, 495 sick and off duty in the lines, or a total of 1,712.

The totals, therefore, off duty on the dates specified were:

It should be stated that the figures quoted above would have been very much larger were it not that a large number of men unfit for duty by reason of venereal and other forms of disease have been returned to Australia, and a considerable number sent to Malta.

There have been returned to Australia by the Kyarra on February 2, the Moloia on March 15, the Suevic on April 28, and the Ceramic on May 4, a total of 337 soldiers who were medically unfit for various reasons, and 341 suffering from venereal disease, or 678 in all. In addition about 450 were sent to Malta. If these soldiers had been added to the list of those reported sick and unfit for duty daily, the number would have considerably exceeded 2,000. The estimate of 2,000 sick and unfit for duty daily was studiously moderate, as pointed out in a private letter to Colonel Fetherston at the time when precise figures could not be immediately obtained.

It is gratifying to find that the amount of sickness is diminishing and that the amount of venereal disease, so far as can be ascertained, is also decreasing.

Strenuous efforts have been made by the A.M.C. to attack both forms of inefficiency by dealing with the causes, and with a view to avoiding future troubles the D.M.S. Egypt has appointed a committee of medical officers to inquire into the causations of the outbreak. It is unlikely that the committee can be very active just at present, because of the prior claims on the time of all concerned owing to the influx of wounded. At a later period it is hoped that an exhaustive report will be furnished for the benefit of future undertakings.

Most strenuous efforts have been made to limit the amount of venereal disease. General Birdwood, Commander-in-Chief of the New Zealand and Australian Army Corps, has personally interested himself in this question, and has through the O.C. First Australian General Hospital arranged for me to visit each troopship on arrival, all leave being stopped from the transport until I have been on board. The practice followed is to interview the commanding officer and the officers of the transports, to explain to them the gravity of the position, and to ask each and all of them to use all the influence he possesses with his men to deter them from exposing themselves to the risk of contagion, to draw their attention to the fact that on the physical fitness of the individual man depends the possibilities of success to the army, and to ask for the loyal and enthusiastic co-operation of every officer in work of such importance from a military point of view, and the point of view of subsequent civil life. The officers immediately parade the men, address them, and convey to each of them a printed message from General Birdwood. General Birdwood's letter to General Bridges, written during the early part of the stay of the Army in Egypt, is handed to the Commanding Officer to be read by him and his staff. There is no doubt that this systematic procedure has drawn attention to the gravity of the problem. It has always been responded to loyally by the officers concerned, and it has certainly limited the action of young and inexperienced men on their first landing in an Eastern country.

Other steps were taken by Surgeon-General Williams, who on arrival in Egypt called a conference of senior medical officers to consider the gravity of the venereal diseases problem.

It is satisfactory to find, notwithstanding the amount of disease which has existed, and which, while not excessive, is still heavy, that the mortality has not been as serious as it might have been. The mortality in No. 1 Australian General Hospital for February and March was seventeen cases out of a total of 3,150 admitted" (Report ends).

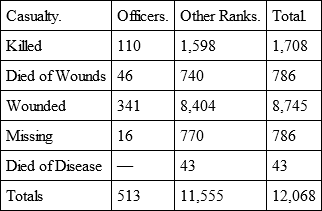

The following return shows the total number of casualties in the Australian Force up to July 16, 1915:

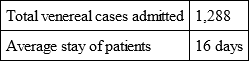

The next table shows the average length of stay in hospital of venereal cases at a particular date:

First Australian General Hospital

Prior to the arrival of the wounded the medical service was inconvenienced by another circumstance. Men were continually arriving with hernia, varix, and other ailments which they had suffered from before enlistment, and which had been overlooked during the preliminary examination in Australia. In one case a soldier suffering from aortic aneurism arrived in Egypt, and similar instances might be given. The examination of recruits in Australia had been conducted by practitioners in country towns and elsewhere, often under conditions highly unfair to the practitioner. There is no doubt that the Government would have been well advised to have withdrawn a few men from private practice altogether, paid them adequate salaries, and made them permanent examiners of recruits. Experience of war demonstrates most completely the folly of sending any one to the front who is not physically fit. It is apt to be forgotten that in warfare there can be no holidays, or days off, and that the human being must be at his maximum of physical efficiency, and his digestion of the best. If his soundness is doubtful it is better to keep him for base duty at home, on guard duty at the base, or as an orderly in the hospital. It is simply a waste of money, and tends to the disorganisation of the service, to send such people anywhere near the fighting line. We made an attempt at one stage to roughly calculate what the Australian Government had lost in money by the looseness of official examination. It was impossible to make an accurate estimate, but the sum was great.

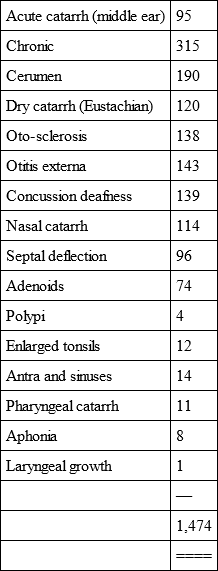

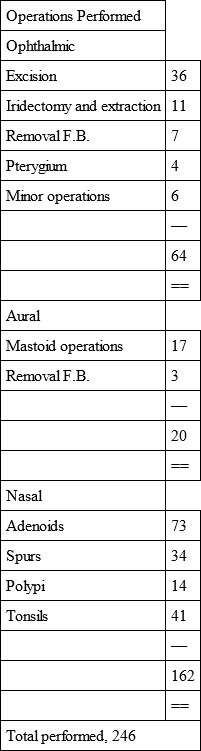

Ophthalmic and Aural WorkWhen one of us joined the hospital as oculist and aurist and registrar (Lieut. – Col. Barrett) he was informed that specialists were not required, but apparently those responsible had formed no conception of the excessive demands which would be made on the ophthalmic and aural departments. The first patient admitted to No. 1 General Hospital was an eye case, and an enormous clinic rapidly made its appearance. It was conducted somewhat differently from an ordinary ophthalmic and aural clinic, in that (by reason of the remoteness of their camps) some patients were admitted for ailments which would have been treated in the out-patient department of a civil hospital. There were usually from 60 to 100 in-patients and there was an out-patient clinic which rose sometimes to nearly 100 a day. It should be remembered that these included few, if any, serious chronic cases, which were at once referred back to Australia. The amount of ophthalmic and aural disease was very great. The figures subjoined show the extent of the work done.

From the opening of the Hospital to September 30, 1915, the patients treated in the Ophthalmic and Aural Department numbered as follows:

The ophthalmic cases may be roughly classified as follows:

The distribution of disease is unusual. In the course of a long and extensive practice one of us (Lieut. – Col. Barrett) had not seen as many cases of adenoids in adults as he examined in Egypt in three months. It seemed that the irritation of the sand containing organic matter caused inflammation and irritation of the naso-pharynx. Of ophthalmia there was a great deal. It was usually of the Koch-Weeks variety, and gave way readily to treatment. There were a few cases of gonorrhœal ophthalmia, two of which arrived from abroad, and all of which did well. After the arrival of the wounded, however, a new set of problems made their appearance. A limited number of men were totally blind, mostly from bomb explosions, and a large number of others had received wounds in one eye or in the orbit. It soon became evident that an eye punctured by a fragment of a projectile is almost invariably lost. The metal is non-magnetic. It is usually situated deep in the vitreous; it is practically impossible to remove it even if the eye were not infected and degenerate. A still more remarkable phenomenon, however, made its appearance. If a projectile enters the head in the vicinity of the eye, and does not actually touch it, in most cases the eye is destroyed. Whether from the velocity or the rotation of the projectile, the bruising disorganises the coats of the eye and renders it sightless. In all such cases, if the projectile was lodged in the orbit, the eye was removed together with the projectile. The total number of excisions was thirty-six. In no case did a sympathetic ophthalmitis make its appearance. The eyes were not removed unless the projection of light was manifestly defective. A fuller account of the precise ophthalmic conditions will be published elsewhere.

If the general physical examination of recruits was defective, it is difficult to find suitable terms to describe the examination of their vision. Instances were not infrequent where men with glass eyes made their appearance, and there were several recruits who practically possessed only one eye. Spectacle-fitting was the chief work, as many of the recruits required glasses, mostly for near work, but sometimes for the distance. Ultimately the War Office decided to provide the spectacles. In such a war, it is impossible to exclude recruits for fine visual defects, still, men with only one eye can hardly be sent to the front.

One remarkable instance occurred. A man suffering from detachment of the retina had but one effective eye. I gave directions that he should not be sent to the front, but he eluded authority, and reached Gallipoli, where he was hit in the blind eye with a projectile. I subsequently removed the eye.

The work was excessive, but only one life was lost, though on occasion the condition of some of the sufferers was grave to a degree. One of the most remarkable cases of injury was that of a man who was struck below the left eye by a bullet which emerged through the back of his neck, to the side of the median line. The bullet in emerging tore away a large quantity of the substance of the neck, leaving a hole in which a fair-sized wine glass could have been placed. He was a cheerful man, and sat up in bed propped with pillows, because of the weakness of his neck, and observed to a visitor "Ain't I had luck!" He made an excellent recovery.

It is remarkable that there should have been so much refraction work, and there is no doubt that a working optician, i. e. spectacle maker, should accompany every army. Men are often just as dependent for their efficiency on glasses as on artificial teeth, and in a war of this character cannot be rejected.

The acute inflammations of the middle ear were of the most severe type, caused temperatures rising to 103° F. and sometimes left men on convalescence as weak as after a serious general illness. The attacks were so vicious that the pathologist, Captain Watson, sought for special organisms, but found only staphylococcus. Probably the same group of organisms which caused vicious pulmonary attacks also caused these severe aural inflammations.

Before our arrival in Egypt malingerers in the force who, having enjoyed a holiday trip to Egypt, wanted to go home again, suddenly discovered that they were blind or deaf. For a time the department was fairly busy detecting the wiles of these men. When they discovered, however, that they would be subjected to expert examination, sight and hearing soon returned. A number of devices were resorted to in order to detect the fraud —i. e. the use of faradisation, blind-folding, and the like – and it was rarely that the impostor escaped.

Other Diseases: Measles and its Complications; Food InfectionsThe danger run by an army from measles is very great indeed, and at an early stage the position was surveyed, and an attempt made to limit the trouble. A cable message was sent to Australia, asking that precautions should be taken against shipping measles cases or contacts. At Suez arrangements were made with the Government Infectious Diseases Hospital to admit any patients suffering from measles or infectious diseases who might land with the recruits. In such cases the clothing of the remaining recruits was disinfected before they were allowed to proceed to Cairo. In this way disease was kept out of Egypt as much as possible. In the case of measles it is not simply temporary disablement, but also the complications and sequelæ which are to be feared. The experience gained has made us converts to the open-air method of treating such cases, at all events in a rainless country like Egypt. Treated on piazzas and in open spaces the cases seem to do better than in hospital wards, and, as far as one can judge without a critical examination, with a lower mortality.

The extent to which the troops suffered from measles and other diseases was the cause of the appointment of a committee to inquire into causation. The committee made some inquiries, but owing to a set of complications never completed its work. There seemed, however, to be a consensus of opinion that the use of the bell tent was objectionable, as it did not ventilate readily, and that the habits of the men contributed to these diseases.

The men were apt to visit Cairo, spend the evenings in the cafés or theatres, ride home in the cold nights in a motor car or tram, get to bed at the last moment possible, and then turn out again for a hard day's work. The opinion of the physicians was that the drilling of men suffering from even a moderate cold was a source of considerable danger. If to these causes be added the neglect of the teeth on the part of many of the men, some explanation may be found for the presence of these diseases. Every effort was made to instruct the men through the regimental officers, and there is no doubt that as time went on the quantity of this type of disease somewhat diminished.

Sunstroke was practically unknown. A number of cases occurred during a severe khamsin, but the use of a looser and lighter uniform, and the adoption of sensible hours of work, prevented any recurrence. Of two deaths known to have taken place the cause was only partly due to heat. The men were warned against the risk of bilharzia, and as they were provided with shower baths there was no inducement to bathe in the muddy pools and canals where bilharzia lurks.

With the provision of dentists another risk was removed, at all events in parts. In hospitals, tooth brushes were supplied in thousands, and every effort was made to get the men to use them.

As the summer wore on, however, another type of disease made its appearance – the intestinal infections which, at first unknown, became so frequent in Gallipoli as to be more serious than fighting. In Gallipoli itself it is difficult to see how they could be prevented. In a limited space there were many dead bodies scantily buried, and consequently myriads of flies. The plentiful use of disinfectant, had it been obtainable, might have been useful, but the difficulties were great. Once the dysenteric organisms were introduced, it was practically impossible to stop the spread of disease.

The Fly PestAt the Island of Lemnos, however, which was not under fire, and where there was room, the conditions appear to have been nearly as bad, and it is somewhat difficult to know why the fly pest could not have been got under at Mudros. At Heliopolis at an early stage the fly problem was seriously tackled. A sanitary officer was appointed, and charged with the duty of dealing with this important matter. The following precautions were adopted. All refuse and soiled dressings were placed in covered bins, which were provided in quantity. These were removed once daily. Any moist ground in the vicinity of these bins was watered with sulphate of iron solution, and sprinkled with chloride of lime. Fly papers in great numbers were distributed throughout the wards. The food in the kitchens, whether cooked or uncooked, was kept under gauze covers or in gauze cupboards. By these means the fly pest was reduced to small proportions. But with the least slackness in administration the flies were again in evidence. It was most instructive to see a floor covered with flies if fluid containing food material had been spilled, and to see dirty clothing covered with masses of flies. A piece of soiled clothing half buried in the desert appears to act as an excellent breeding-place.

It was impracticable in Egypt to cover all the windows and doors with fly-proof netting. The exclusion of the air in the hot weather would have been troublesome, and the best type of netting was not obtainable. Furthermore the precautions already enumerated kept the pest under in Heliopolis.

The fly problem was one of the most serious the army had to face. The passage of a dysenteric stool by a man who is really ill was often followed by the entry into his anus of flies before an attendant had time to intervene. Each of these flies might then become a source of infection and had only to light on a piece of food, cooked or uncooked, to cause further damage.

Circular issued by the Officer Commandingthe HospitalDestruction and Prevention of FliesOutside.

1. No rubbish heaps will be allowed.

2. All manure heaps shall be sprayed twice a week with sulphate of iron – 2 lb. to 1 gallon of water.

3. All food in the Arab quarters shall be kept in a closed cupboard.

4. All rubbish boxes and open receptacles shall be removed from the premises and neighbourhood.

5. No receptacles other than iron tins with lids kept closed will be allowed to be used for refuse.

6. Every place on which garbage has been exposed shall be freely sprinkled with chloriated lime.

Wards.

1. All food and receptacles for food shall be kept constantly covered.

2. All spit-cups shall be kept covered.

3. All remains of food shall be removed at once to receptacles which are to be kept covered completely and constantly except when uncovered necessarily to receive waste materials.

4. Sisters-in-Charge shall use a liberal quantity of fly papers. Surgical soiled dressings shall be placed in special bins which shall be kept covered.

Kitchen and Mess Rooms.

1. All food shall be kept locked up or completely covered.

2. All remains of food shall be treated as in the wards. The responsible officer shall use a liberal supply of flat or hanging fly papers.

It need hardly be said that the enforcement of even these simple precautions is more difficult than giving the order.

A good sanitary officer, however, acting on these directions, can and did reduce the fly danger to small proportions. The flies were never exterminated, but were kept well under. The least slackness, however, ended in their rapid reappearance. As they are in all probability the principal cause of the gastro-intestinal infections, the matter is one of the first importance.

Typhoid fever made its appearance, and a proper statistical investigation should be made later on to show the extent of the damage done. The general impression respecting the result of the inoculation to which all the troops were subjected was that the disease was not so frequent and certainly not nearly so fatal as it otherwise would have been. Deaths were few.

The men had not been inoculated against paratyphoid, so that exact conclusions will be difficult to draw even when figures become available.

Many people suffered from Egyptian stomach ache, a form of disease which is as unpleasant as it is exhausting. It manifests itself by repeated attacks of colicky pain, apparently usually associated with the colon. The severity of the pains is remarkable, and the persistent recurrence speedily ends in a considerable degree of exhaustion. It is almost certainly due to food infection.

It is obvious that the business of a sanitary medical officer is not merely to inspect buildings and kitchens, but to spend an hour or two a day in the kitchen quietly watching the preparation of the food and giving the necessary instruction and supervision to those who are preparing it. The inefficiency caused by food infections has probably done more harm than many battles. In the camps similar troubles occurred. By reason of the lack of cold storage and the high temperature, rotten food was not uncommon, and caused outbreaks of incapacitating diarrhœa and ptomaine poisoning.

When, however, the problem is surveyed dispassionately, the remarkable feature of the work at Heliopolis and in Cairo was the low mortality, as the following table will show:

Burials in Old Cemetery, CairoFrom Arrival of Australians in Egypt, December 5,1914, to August 14, 1915

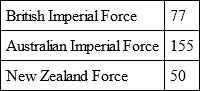

In view of this extraordinarily low mortality, it is interesting to comment on human intellectual frailty. It was said that the hospitals were septic, that operations of election could not be performed with safety, that the climate was particularly dangerous, and so forth. One letter which reached us made reference to hundreds of deaths of brave fellows due to faulty camp and hospital conditions. Yet here is the fact recorded that the total deaths in Cairo amongst Australians from disease and wounds to August 14 were only 155. All men tend to generalise on insufficient instances, and the tendency in this case was aggravated by some physical discomfort experienced by the generalisers throughout an unusually warm summer – a discomfort accentuated by overwork and a conscientious devotion to duty under trying conditions.

The Egyptian Climate againDealing with the surgical side of the matter, nothing was commoner at one time than to hear the statement made that owing to the hot weather septic infections were common, that wounds did not heal as they should in Egypt, and that it was not a suitable place to which wounded men should be sent. While quite agreeing with the critics that a cool climate is always preferable to a hot one, it may be remarked that in the first place summer in Egypt, apart from the khamsin, is not excessively hot. The khamsin blows for a certain number of days in April, May, and the first half of June. The temperature may rise to 112° or more. The wind blows with a fiery blast, and there is no doubt it is exceedingly trying. But if buildings are shut up early in the morning and opened at night, even the khamsin may be made tolerable. After the middle of June, however, there is very little wind. One day is very like another. The midday temperature is from 90° to 95° Dry Bulb, and the nights perhaps 65° to 70° Dry Bulb. The Wet Bulb temperatures are set out in the table previously referred to.

For the most part men slept in nothing but pyjamas. No sheet is wanted until towards the end of August. Whilst it is not pleasant to wake in the mornings in a lather, nevertheless, if a practical and cold-blooded examination be made of the facts, the result shows nothing but discomfort.

Grave septic diseases did not occur. The hospitals were perfectly clean, and at Luna Park in particular we have the testimony of Colonel Ryan that the wounds healed by first intention and that the cases did excellently.

As the garrison of Egypt was a very large one, and as Australian troops were continually pouring into it, it was impracticable even if it had been necessary to take the patients anywhere else. The islands of Lemnos and Imbros were far less suitable even for those who had been injured at Gallipoli, and apart from the inconvenience caused by the heat there was no reasonable ground for complaint in Egypt. Furthermore the heat is not tropical. It is subtropical, as the Wet Bulb temperatures indicate.