полная версия

полная версияOld Church Lore

At this time, commenced a literary warfare, in the form of pamphlets, respecting the cross. These were followed by its destruction. Robert Harlow was deputed by Parliament to carry out the work. He went to the cross with a troop of horse and two companies of foot soldiers. How completely he executed his orders may be gathered from the official account. It states: “On the 2nd of May, 1643, the cross in Cheapside was pulled down. At the fall of the top cross, drums beat, trumpets blew, and multitudes of caps were thrown in the air, and a great shout of people with joy. The 2nd of May, the almanack says, was the invention of the cross, and the same day, at night, were the leaden popes burnt [they were not popes, but eminent English prelates] in the place where it stood, with ringing of bells and a great acclamation, and no hurt at all done in these actions.”

The author of “The Old City” (London, 1865), a work to which we have been indebted for some of the particulars included in this paper, adverts to a curious tract published on the day the cross was destroyed. It bears the following title: “The Downfall of Dagon; or, the taking down of Cheapside Crosse; wherein is contained these principalls: 1. The crosse sicke at heart. 2. His death and funerall. 3. His will, legacies, inventory, and epitaph. 4. Why it was removed. 5. The money it will bring. 6. Noteworthy, that it was cast down on that day when it was first invented and set up.” An extract or two from this publication can hardly fail to interest the reader. “I am called the ‘Citie Idoll,’” says the tract, “the Brownists spit at me, and throw stones at me; the Famalists hide their eyes with their fingers; the Anabaptists wish me knockt in pieces, as I am to be this day; the sisters of the fraternity will not come near me, but go by Watling Street, and come in again by Soaper Lane, to buy provisions of the market folks… I feele the pangs of death, and shall never see the end of the merry month of May; my breath stops – my life is gone; I feel myself a-dying downards.” The bequests embrace the following: “I give my iron work to those which make good swords at Hounslow, for I am Spanish iron and steele to the backe. I give my body and stones to those masons that cannot telle how to frame the like againe, to keep by theme for a patterne, for in time there will be more crosses in London than ever there was yet.” The epitaph is as follows:

“I looke for no praise when I am dead,For, going the right way, I never did tread.I was harde as an Alderman’s doore,That’s shut and stony-hearted to the poore.I never gave almes, nor did anythingWas good, nor e’er said, ‘God save the King.’I stood like a stock that was made of wood,And yet the people would not say I was good,And, if I tell them plaine, they’re like to mee —Like stone to all goodnesse. But now, reader, seeMe in the dust; for crosses must not stand,There is too much crosse tricks within the land;And, having so done never any good,I leave my prayse for to be understood;For many women, after this my losse,Will remember me, and still will be crosse —Crosse tricks, crosse ways, and crosse vanities.Believe the crosse speaks truth, for here he lyes.”The Biddenden Maids Charity

For several centuries, the strange story of the Biddenden Maids, was told by sire to son, and, in course of time, was made the subject of a broadside, which has become rare, and is much prized by collectors of historical curiosities.

The tale is to the effect that, in the year of our Lord, 1100, at the village of Biddenden, in the county of Kent, were born Eliza and Mary Chulkhurst, commonly called “The Biddenden Maids.” It is asserted that the sisters were joined together by the hips and shoulders.

There is not a record of any attempt being made to separate the couple, and they grew up together. When they had attained the age of thirty-four years, one of the sisters was taken ill, and shortly afterwards died. The surviving one was entreated to submit to a surgical operation being performed, and have her body separated from that of her deceased sister, but she firmly refused. She was prepared to die. “As we came together,” she said, “we will also go together.” Her life closed about six hours after that of her sister.

The claims of the poor were not overlooked. The sisters, in their will, bequeathed to the churchwardens of the parish of Biddenden, a piece of land which is known as “Bread and Cheese Land.”

The rent of it realises a considerable sum of money, which is largely distributed to the poor of the place in bread and cheese.

The memory of the wonderful women is maintained by the distribution, on Easter Sunday, of about a thousand small cakes made of flour and water, and having impressed upon them rude representations of the Maids.

Hone, in his “Every Day Book,” gives a picture of the cake he received in 1826, which we reproduce. It is the exact size of the one sent to him. Since Hone’s time a new stamp or mould has been made, and the old style of representing the Maids has not been followed in every detail. In the cut we give, it will be noticed no legs appear, now they are represented on the cakes.

In addition to the small cakes presented to strangers as well as villagers, every resident in the parish is entitled to a threepenny loaf and three quarters of a pound of cheese. The charity was formerly delivered at the tower door of the church, but since some alterations have been made in the building, the distribution takes place at the old workhouse. The congregation, on Easter Sunday afternoon, after which service the cakes are given, is always very large, many persons coming from the surrounding villages.

Halsted, the historian of Kent, discredits the traditional origin of the old custom. A similar story is related of two females, whose figures appear on the pavement of Norton St. Philip’s Church, Somersetshire.

Plagues and Pestilences

The graphic pages of Daniel Defoe have made the reader familiar with the terrible story of the Great Plague of London, which began in December, 1664, and carried off 68,596 persons, some say even a larger number. To give a detailed account of that visitation would be to relate an oft-told tale. Some important facts, not generally known, respecting old-time plagues and pestilences may be gleaned from parish registers and churchwardens’ accounts, and it is from such records that we propose mainly to draw materials for this chapter.

When a town was infected with the plague, business was suspended, and the inhabitants isolated from the neighbouring places. If a person desired to travel at large, he made application to the Mayor or Chief Magistrate, and obtained a certificate to the effect that he was not suspected of the plague.

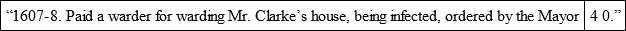

In many towns, great wisdom was displayed by erecting huts on breezy moors and other places away from the busy haunts of men, for the reception of the plague-stricken persons, and to which they were removed. The inmates of a house were not suffered to leave the homes from whence the patients had been removed. An order passed in London, in 1570, states: “Howses, having some sicke, though none die, or from whence some sicke have been removed, are infected houses, and such are to be shutt upp for a moneth. The whole family to tarrie xxviii daies.” Round the houses, watch and ward were constantly kept to prevent egress. Certain boundaries were defined, and these could not be passed. The watchers provided the inmates of the houses with food, etc., and took messages to their friends. In the churchwardens’ accounts of St. Mary, Woolchurch, Haw, is an entry: —

On the door of the infected house was the sign of a cross, in a flaming red colour, with the pathetic prayer, “Lord, have mercy on us.” In old churchwardens’ accounts, many items like the following, drawn from the accounts of St. Mary, Woolnoth, London, might be quoted:

These crosses were about a foot in length. More than one student of the past has suggested that the practice of marking the doors of infected houses with red crosses arose from the injunction given to Moses at the institution of the passover. The crosses served the important purpose for which they were intended, namely, to caution folk against going to infected houses.

Queen Elizabeth, in 1563, commanded that the inmates of a house which had been visited by the plague should not go to church for a month.

Orders were given that any dogs found in the streets were to be killed. An order, bearing on this matter, made in May, 1583, at Winchester, may be reproduced: “That if any house wtn this cytie shall happen to be infected with the Plague, that thene evye persone to keepe within his or her house every his or her dogg, and not to suffer them to goo at large: And if any dogg be then founde abroad at large, it shall be lawful for the Beadle or any other person to kill the same dogg: and that any Owner of such Dogg going at large shall lose 6s.” It was believed that dogs conveyed contagion from infected houses. A passage in Homer’s “Iliad” has a reference to man obtaining infection from an animal. It relates to the great pestilence that prevailed in the Grecian army:

“On mules and beasts the infection first began,At last, its vengeful arrows fix’d in man;Apollo’s wrath the dire disorder spread,And heap’d the camp with mountains of the dead.For nine long nights throughout the dusky air,The funeral torches shed a dismal glare.”Many remedies were tried to stay the progress of plagues. The ringing of church bells was among the number. “Great ringing of bells in populous cities,” says Bacon, in his “Natural History,” “disperseth pestilent air, which may be from the concussion of the air, and not from the sound.” Music, in the Middle Ages, was believed to have a healing power. Large fires were lighted in houses and streets as preventatives. It is not unlikely that the practice may be derived from the fact that, in 1347, during the time of the plague raging at Avignon, Pope Clement VI. caused great fires to be kept in his palace, day and night, and by this means believed he had kept the pestilence from his household. In 1563, we learn from Stow that a commandment came from Queen Elizabeth that “every man in every street and lane should make a bonefire three times a week, in order to the ceasing of the plague, if it so pleased God, and so to continue these fires everywhere, Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays.”

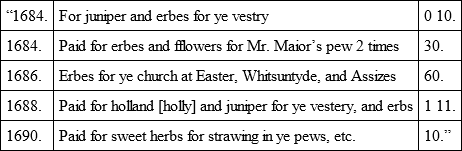

It is asserted in Rome, in A.D. 195, that for some time, 5,000 persons died daily of a fearful plague. The physicians were unable to check its deadly course. It lasted for three years. The doctors of the day urged upon the people to fill their noses and ears with sweet smelling ointments to prevent contagion. We learn from Defoe’s “Journal of the Plague Year, 1665,” how largely perfumes, aromatics, and essences, were employed to escape contagion at that time. Says Defoe, if you went into a church where any number of people were present, “there would be such a mixture of smells at the entrance, that it was much more strong, though, perhaps, not so wholesome, than if you were going into an apothecary’s or druggist’s shop. In a word, the whole church was like a smelling bottle; in one corner, it was all perfumes; in another, aromatics, balsamics, and a variety of drugs and herbs; in another, salts and spirits; as every one was furnished for their own preservation.” He further says: “The poorer people, who only set open their windows night and day, burnt brimstone, pitch, and gunpowder, and such things in their rooms, did as well as the best.”

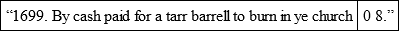

The annals of many of the northern English towns contain numerous sad references to plagues. Newcastle-upon-Tyne, for example, suffered much. The churchwardens’ accounts of St. Nicholas contain records of payments which bear on this subject. We find, for instance, the following item:

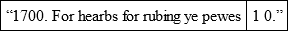

Fires were made in churches in movable pans. A year later, we read:

In courts of justice, might be seen large nosegays, not for ornament, but as preservatives against the pest. The Rev. J. R. Boyle, F.S.A., has gone carefully over the churchwardens’ accounts of St. Nicholas’, now the Cathedral of the city of Newcastle, and reproduced some curious items in his guide to the building. Here follow a few of the items:

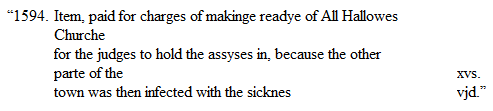

Mr. William Kelly, read before the Royal Historical Society, on July 12th, 1877, an important paper on “Visitations of the Plague at Leicester.” He gave particulars of the Mayor addressing a letter to Justice Gawdie, who was about to visit the town in his official capacity. He was informed that the plague had broken out in houses near the castle, and it was concluded that his lordship would not come to preside so near the infected places. The result of the communication may be gathered from the following entry, copied from the chamberlain’s accounts:

We have previously stated, that persons wishing to leave a plague-stricken town, for the purpose of travelling, were obliged to obtain passes. Mr. Kelly gives a copy of one of these documents, which we reproduce in extenso. It reads as follows:

“Villa Leic. Theise are to certifie all the Queenes Majesties officers and lovinge subjects, to whom theise presents shall come, that the bearer, Alice Stynton, the wief of John Stynton, of the towne of Leycester, pettye chapman, dothe dwell and inhabyte in the parish of St. Nicholas, in the said town, in a streete called the Sore Laine, neyre unto the West Brigge.

The which John Stynton hathe not bene in Leycester sythence one fortnytt after St. James Daye last; but travelinge abrode in Northamptonshier about his lawfull affaires in gaytheringe under the Greate Seale of England, by lycence, for a poore house at Waltam Crosse.

And this bearer, his wief, with hym all the said tyme, untill her nowe comyng hom to Leycester, which was aboute a weeke past. The which bearer her dwellyng ys not neyre unto places suspected of the plage, but ys cleyre and sound from the same, God be thancked, neyther ys there any att this present sicke thereof in the said streete or parish, God be praised. Do therefore request you to permytt and suffer her quietlye to travell to her husband, and also to permytt and suffer her said husband and her quietlye, upon ther honest behavire, to travell aboute ther lawfull busynes withoute any your hyndrance, and you the constables to helpe them to lodginges in ther said travell yf such nede shall require. In witnes whereof, we the mayor and alderman of the saide towne of Leycester have hereunto subscribed our names, and sette the seale of office of the said mayor, this vjth daye of October 1593, Aº 35º Eliz.”

The records of Beverley supply some important notes respecting persons leaving the place. We gather from George Oliver’s history of Beverley, that the plague raged with great violence in the year 1610, death and desertion were greatly thinning the town; the corporation made an order, directing that a fine of ten shillings be imposed on every individual leaving the town, even to go to fairs and markets, without the mayor’s special permission. If the preceding measure was insufficient to detain persons in Beverley, it was resolved to imprison or otherwise punish, at the discretion of the justices, those offending.

The head of every family had to report periodically, during the time of the plague, to the constable in his ward, the state of the health of his household. If the disease attacked any member of his family, or those under his charge, and he neglected, within a specified number of hours, to report the matter, he was liable to a fine of forty shillings, to be placed in the town’s chest.

The town of Derby suffered greatly from a plague in 1592-3. It appears to have been imported in some bales of cloth from the Levant to London, and quickly spread into the provinces. In the parish register of St. Alkmund’s, Derby, under October, 1592, is this statement, “Hic incipit pestis prestifera.” It took twelve months to run its destructive course.

The register of All Saints’, Derby, under October, 1593, says: “About this time, the plague of pestilence, by the great mercy and goodness of Almighty God, stay’d, past all expectac’on of man, for it rested upon assondaye, at what tyme it was dispersed in every corner of this whole p’she: ther was not two houses together free from ytt, and yet the Lord bade his angell staye, as in Davide’s tyme: His name be blessed for ytt.”

The inhabitants of Derby suffered greatly from a plague in 1665. In the Arboretum of the town is a memorial of the visitation, in the form of a stone, bearing the following inscription:

“Headless Cross, orMARKET STONEThis Stone FORMED PART OF AN ANCIENT CROSS AT THE UPPER END OF FRIAR GATE, AND WAS USED BY THE INHABITANTS OF DERBY AS A MARKET STONE DURING THE VISITATION OF THE PLAGUE, 1665. IT IS THUS DESCRIBED BY HUTTON IN HIS HISTORY OF DERBY.

‘1665. Derby was again visited by the plague at the same time in which London fell under that severe calamity. The town was forsaken; the farmers declined the Market-place; and grass grew upon that spot which had furnished the supports of life. To prevent a famine, the inhabitants erected at the top of Nuns-green, one or two hundred yards from the buildings, now Friar-gate, what bore the name of Headless-cross, consisting of about four quadrangular steps, covered in the centre with one large stone; the whole near five feet high; I knew it in perfection. Hither the market-people, having their mouths primed with tobacco as a preservative, brought their provisions, stood at a distance from their property, and at a greater from the townspeople, with whom they were to traffic. The buyer was not suffered to touch any of the articles before purchase; but when the agreement was finished, he took the goods, and deposited the money in a vessel filled with vinegar, set for that purpose.’”

Tobacco has long been regarded as an efficacious preservative against disease. There is a curious entry in Thomas Hearne’s Diary, 1720-21, bearing on this matter. He thus writes, under date of January 21st: “I have been told that in the last great plague in London none that kept tobacconists’ shops had the plague. It is certain that smoaking was looked upon as a most excellent preservative. In so much, that even children were obliged to smoak. And I remember that I heard formerly Tom Rogers, who was yeoman beadle, say that, when he was that year, when the plague raged, a school-boy at Eaton, all the boys of that school were obliged to smoak in the school every morning, and that he was never whipped so much in his life as he was one morning for not smoaking.”

Charles Knight, in his “Old England,” gives an original drawing of the Broad Stone, East Retford, Nottinghamshire. He says, on this stone, money, previously immersed in vinegar, was placed in exchange for goods, during the Great Plague.

In front of Tothby House, near Alford, Lincolnshire, under a spreading tree, is a large stone, which formerly stood on Miles Cross Hill, and, when the town was plague-stricken, in the year 1630, on this stone, money immersed in vinegar was deposited, in exchange for food brought from Spilsby and other places. From July 22nd, 1630, to the end of February, 1631, 132 burials are recorded in the parish register, and this out of a population of under 1000 persons, a proportion equal to that of London during the Great Plague. In one homestead, within twelve days, were six deaths. The Rev. Geo. S. Tyack, B.A., who has contributed a carefully-prepared chapter to “Bygone Lincolnshire” on this theme, does not state how the scourge was brought to Alford.

The dead were, as a rule, buried at night, without coffin and ceremony, and frequently in a common grave outside the usual graveyards, like, for example, those in the pest pit of London. “Bring out your dead! Bring out your dead!” was the dismal cry which was heard in London during the Great Plague. The people were dead and buried in a few hours, and it is believed that many were interred alive. A well-known instance occurred at Stratford-on-Avon. The plague raged at the town in 1564, and swept away one-seventh of the inhabitants. The council chamber was closed, but the councillors did not neglect their duties; they met in a garden to discuss the best means of helping the sufferers. The visitation was not confined only to the homes of the poor. The Manor House of Clopton was attacked, and one of its fair inmates, a beautiful girl named Charlotte Clopton, was sick, and to all appearance died. She was buried without delay in the family vault, underneath Stratford Church. A week passed, and another was borne to the same resting place. When the vault was opened, a terrible sight was presented. Charlotte Clopton was seen leaning against the wall in her grave clothes. She had been buried alive, and, on recovering from the plague, had attempted to get out of the vault, when death had ended her sufferings.

At Bradley, in the parish of Malpas, Cheshire, an entire family, named Dawson, consisting of seven members and two servants, died of the plague, in the year 1625. One of Dawson’s sons had been in London, and returned home sick, died, and infected the whole household. The deaths commenced towards the end of July and ended September 15th. Respecting Richard Dawson, the following particulars are given in the parish register, after stating that he was the brother of the head of the house: “being sicke of the plague, and perceyving he must die at yt time, arose out of his bed and made his grave, and caused his nefew, John Dawson, to cast strawe into the grave, w’ch was not farre from the house, and went and lay’d him down in the say’d grave, and caused clothes to be layd uppon, and so dep’ted out of this world; this he did, because he was a strong man, and heavier than his said nefew and another wench were able to bury. He died about xxivth of August. Thus much I was credibly tould he did.” The next entry in this distressing record bears date of August 29th, and is that of the nephew just named, and, on September 15th, Rose Smyth, the servant, doubtless the wench referred to, was buried, “and the last of yt household.”

At Braintree, in Essex, in 1665, the plague made great ravages. In that year, 665 persons died of it, being fully one-third of the inhabitants of the place. Business was at a standstill, the town was shunned, and the inhabitants had to depend on charity. Long grass grew in the streets, and the whole place was one of desolation. At this time, Dr. Kidder, afterwards Bishop of Bath and Wells, was looking after the spiritual welfare of the place. His life contains a painful picture of the sufferings of the inhabitants. In his own house, a young gentleman was attacked and died. “My neighbours,” he writes, “durst not come near, and the provisions which were procured for us were laid at a distance, upon a green before my house. No tongue can express the dismal calamity which that part of Essex lay under at that time. As for myself, I was in perpetual danger. I conversed daily with those who came from the infected houses, and it was unavoidable. The provisions sent into the neighbouring infected town were left at the village where I was, and near my house. Thither the Earl of Warwick sent his fat bullocks, which he did every week give to the poor of Braintree. The servants were not willing to carry them further. This occasioned frequent coming from that infected place to my village, and, indeed, to my very door. My parish clerk had it when he put on my surplice, and went from me to his house, and died. Another neighbour had three children, and they all died in three nights immediately succeeding each other, and I was forced to carry them to the churchyard and bury them. We were alarmed perpetually with the news of the death of our neighbours and acquaintances, and awakened to expect our turns. This continued a great part of the summer. It pleased God to preserve me and mine from this noisome pestilence. Praised be his name.” The plague at Colchester, in the same county, in 1665-6, made the death rate higher than that of the neighbouring town or even of London. Its deadly operations opened in August, 1665, and closed in December, 1666, and, in that period, passed away 4,731 persons. Poverty prevailed, but help poured in from many places. Weekly collections were made in the churches of London, and by this means the sum of £1,311 10s. was obtained. The oath book of the Corporation contains the form of oath administered to men known as “Searchers of the Plague.” It was the duty of the men to search out and view the corpses of all who died, and, in cases of death from the plague, to make known the fact to the constables of the parish, and the bearers appointed to bury them. The searchers had to live together, and apart from their families, and not go abroad, except in execution of their duty. They were careful not to go near any one, and they carried in their hands white wands, so that people might know them and so avoid them.