полная версия

полная версияOld Church Lore

A good anecdote is related in Dawson’s “History of Skipton,” respecting Sunday football playing. It is stated that the Rev. J. Alcock, B.A., of Burnsall, was on his way to conduct afternoon service, when he saw a number of boys playing football. “With a solemn shake of the head,” says Mr. Dawson, “he rebuked them. ‘This is very wrong, you are breaking the Sabbath!’ The remonstrance fell unheeded, and the next moment the ball rolled to Mr. Alcock’s feet. He gave a tremendous kick, sending it high in the air. ‘That’s the way to play football!’ he said to the ring of admiring athletes, and then, amidst their universal praise, he proceeded on his way to church.”

Bowling was, in bygone ages, a popular Sunday pastime. Ladies appear to have greatly enjoyed the sport. Charles I. and Archbishop Laud were both very fond of bowling. When Laud was taken to task for playing on Sunday, he defended himself by showing that it was well known to be one of the favourite amusements of the Church of Geneva. When John Knox, the Scottish reformer, visited Calvin, he arrived on a Sunday, and found Calvin enjoying a game at bowls. It is not stated if Knox joined in the pastime, but we certainly know that he travelled, wrote letters, and even entertained Ambassadors and others on this day. On a Sunday, in the year 1562, Knox attended the marriage of James Stuart (afterwards the Earl of Murray), and it is asserted that he countenanced a display which included a banquet, a marquee, dancing, fireworks, etc. Not a few of the godly lifted up their voices in condemnation, not so much, we infer, on account of the day, but the extravagances to which the amusements were carried. About half a century later, was married, on Shrove Sunday, 1613, Frederick, the Prince Palatine, and the Princess Elizabeth. The day ended, we are told, according to the custom of such assemblies, with dancing, masking, and revelling. In the works of Shakespeare and other dramatists will be found many allusions to Sunday weddings.

We gather from numerous Acts of Parliament, and other sources, that, after attending church, the people in the old days devoted themselves to “honest recreation and manly sports.” Particular attention was paid to the practice of archery. Richard II., for example, in the year 1388, directed that his subjects, who were servants of husbandry, and artificers, should use the bow on Sundays and other holidays, and they were enjoined to give up “tennis, football, dice, casting the stone, and other importune games.” The next king, Henry IV., strictly enforced the statute made by his predecessor, and those who infringed it were liable to be imprisoned for six days.

Sunday was a great day for bear baiting. It was on the last Sunday of April, 1520, that part of the chancel of St. Mary’s Church, Beverley, fell, killing fifty-five people, who had assembled for the celebration of mass. A bear baiting, held in another part of the town, at the same time, had drawn a much greater crowd together, and hence the origin of the Yorkshire saying, “It is better to be at the baiting of a bear, than the singing of a mass.” At an accident in a London bear-garden, the people did not fare so well, for we learn that on a “Sunday afternoon, in the year 1582, the scaffolds being overcharged with spectators, fell during the performance, and a great number of persons were killed or maimed by the accident.”

We get a good idea of the Sunday amusements in vogue at the time of Elizabeth, from a license the Queen granted to a poor man, permitting him to provide for the public certain Sunday sports. “To all mayors, sheriffs, constables, and other head officers within the county of Middlesex. – After our hearty commendations, whereas we are informed that one John Seconton, poulter, dwelling within the parish of St. Clement’s Danes, being a poor man, having four small children, and fallen into decay, is licensed to have and use some plays and games at or upon several Sundays, for his better relief, comfort, and sustentation, within the county of Middlesex, to commence and begin at and from the 22nd of May next coming, after the date hereof, and not to remain in one place above three several Sundays; and we, considering that great resort of people is like to come thereunto, we will and require of you, as well for good order, as also for the preservation of the Queen’s Majesty’s peace, that you take with you four or five of the discreet and substantial men within your office or liberties where the games shall be put in practice, then and there to foresee and do your endeavour to your best in that behalf, during the continuance of the games or plays, which games are hereafter severally mentioned; that is to say, the shooting with the standard, the shooting with the broad arrow, the shooting at twelve score prick, the shooting at the Turk, the leaping for men, the running for men, the wrestling, the throwing of the sledge, and the pitching of the bar, with all such other games as have at any time heretofore or now be licensed, used, or played. Given the 26th day of April, in the eleventh year of the Queen’s Majesty’s reign.” – [1569.]

The Puritans were making their power felt early in the seventeenth century, and doing their utmost to curtail Sunday amusements. The history of the north of England supplies not a few facts bearing on this matter. One illustration we may give you as an instance of many which might be mentioned. Elias Micklethwaite filled the office of chief magistrate of York, in the year 1615, and during his mayoralty, he attempted to enforce a strict observance of the Sabbath. During the Sunday, he kept closed the city gates, and thus prevented the inhabitants from going into the country for pleasure.

Speaking of city gates, we are reminded of the fact that great precaution used to be taken against the Scotch in the North of England. Many were the battles between the men of England and Scotland. A Scotchman was not formerly permitted to enter the city of York without a license from the Lord Mayor, the Warden, or the Constable, on pain of imprisonment. In 1501, hammers were placed on each of the bars for Scotchmen to knock before entering.

To return to Sunday amusements, James I., in the year 1617, coming from Scotland to London, passed through Lancashire, and was received with every token of loyalty. He was entertained at Hoghton Tower in a manner befitting a monarch. It is not without interest to state how the king and his suite spent the Sunday at this stronghold on the 17th August, 1617. A sermon was first preached by Bishop Morton; next, dinner was served, which was of a substantial character. About four o’clock, a rush-bearing, preceded by “piping,” was witnessed by the king. After the rustic merriment, the company partook of supper, which was almost as formidable as the dinner. After supper, the king repaired to the garden, and a masque of noblemen, knights, and gentlemen passed before him. Speeches were made, and lastly, the night was concluded by “dancing the Huckler, Tom Bedlo, and the cowp Justice of the Peace.” It is stated that Bishop Morton condemned the profaneness of the company who had disturbed the service at the church. During the king’s visit to the country, it is recorded that a large number of the tradesmen, peasants, and servants, of the County Palatine, presented a petition, praying that they might be permitted to have the old out-door pastimes after the services at the church were over. The king granted their request, and issued a proclamation from his palace, at Greenwich, on May 24th, 1618, sanctioning various sports after divine service on Sunday. It was meant only for Lancashire. The recreations named are dancing, archery, leaping, vaulting, May games, Witsun-ales, morris-dancers, and setting up of May-poles. The document, known as the “Book of Sports,” gave considerable offence to the Puritans. Clergymen were directed to read it in their churches.

The question came forward under the next king, Charles I., and on October 18th, 1633, he ratified and published his father’s declaration. This action, in many quarters, was most displeasing, and a number of the clergy refused to read the order. One of the ministers was, in 1637, deprived and excommunicated by the High Commission Court for not acceding to the request. Six years later, namely, in 1643, the Lords and Commons ordered the “Book of Sports” to be burned by the common hangman, at Cheapside and other public places.

We have now brought down our investigations to the days of the Commonwealth. King Charles’s life closed in a tragic manner, at the hands of the headsman, on a scaffold erected before one of the windows of the Palace of Whitehall. Old times are changed, and old manners gone; a stranger fills the Stuart throne. In our pity for unfortunate Charles, we must not forget that English life under the Stuarts became demoralised, the court setting a baneful example, which the people were not slow to follow. Licentiousness and blasphemy were mistaken for signs of gentility, and little regard was paid to virtue. Debauchery was general, and at the festive seasons was carried to an alarming extent. The Puritans, with all their faults, and it must be admitted that their faults were many, had a regard for sound Christian principles; and the prevailing lack of reverence for virtue, morality, and piety, was most distasteful to them, and caused them to try to put an end to the follies and vices of the age.

Various Acts of Parliament were passed to check work and amusement on the Lords Day. We get from the Puritans our present manner of observing Sunday. The following are a few extracts from the “Directory of Public Prayers, reading of the Holy Scriptures,” etc., which was adopted by the Puritan Parliament in 1644. It is therein stated:

“The Lord’s Day ought to be so remembered beforehand, as that all worldly business of our ordinary callings may be so ordered, and so timely and seasonably laid aside, as they may not be impediments to the due sanctifying of the day when it comes.

The whole day is to be celebrated as holy to the Lord, both in public and in private, as being the Christian Sabbath, to which ends it is requisite that there be a holy cessation or resting all the day, from all unnecessary labour, and an abstaining not only from all sports and pastimes, but also from all worldly words and thoughts.

That the diet on that day be so ordered as that neither servants be unnecessarily detained from the public worship of God, nor any other persons hindered from sanctifying that day.

That there be private preparation of every person and family by prayer for themselves, for God’s assistance of the minister, and for a blessing upon the ministry, and by such other holy exercises as may further dispose them to a more comfortable communion with God in his public ordinances.

That all the people meet so timely for public worship that the whole congregation may be present at the beginning, and with one heart solemnly join together in all parts of the public worship, and not depart till after the blessing.

That what time is vacant, between or after the solemn meetings of the congregation in public, be spent in reading, meditation, repetition of services (especially by calling their families to an account of what they have heard, and catechising of them), holy conferences, prayer for a blessing upon the public ordinances, singing of Psalms, visiting the sick, relieving the poor, and such like duties of piety, charity, and mercy, accounting the Sabbath a delight.”

Earnest attempts were made to improve the morals of the people, but the zeal of the Puritans was often not tempered with mercy, and frequently displayed a want of common-sense. In America, the Puritans made some very curious Sunday laws. Walking, riding, cooking, and many other natural needs of life were forbidden. Sports and recreations were punished by a fine of forty shillings and a public whipping. In New England, a mother might not kiss her child on a Sunday. An English author, visiting America in the year 1699, supplies interesting details anent Sunday laws at that time. Says the traveller: “If you kiss a woman in public, though offered as a courteous salutation, if any information is given to the select members, both shall be whipped or fined.” As a slight compensation for the severity of the regulation, he adds that the “good humoured lasses, to make amends, will kiss the offender in a corner.” He adverts to the captain of a ship, who, on his return from a long voyage, met his wife in the street, and kissed her, and for the offence had to pay ten shillings. Another Boston man was fined the same amount for kissing his wife in his own garden. The culprit refused to pay the money and had to endure twenty lashes.

Tobacco, in Virginia, took the place of money as a medium of exchange. A person absenting himself from church was fined one pound of tobacco, and for slandering a clergyman, eight hundred pounds. Ten pounds covered the cost of a dinner, and eight pounds a gallon of strong ale, and innkeepers were forbidden to charge more.

An important Act was passed in the reign of Charles II., in the year 1676, for the better observance of the Lord’s day. It prohibited travelling, the pursuit of business, and all sales, except that of milk. Old church records and other documents contain numerous references to Sunday travelling, and, as an example, we may state that it appears, from the books of St. James’s Church, Bristol, at a vestry meeting, held in 1679, four persons were found guilty of walking “on foot to Bath on Lord’s day,” and were each fined twenty shillings.

In past ages, attending church was not a matter of choice, but one of obligation. Several Acts of Parliament were made bearing on this subject. Laws of Edward VI. and of Elizabeth provided as follows: “That every inhabitant of the realm or dominion shall diligently and faithfully, having no lawful or reasonable excuse to be absent, endeavour themselves to their parish church or chapel accustomed; or, upon reasonable let, to some usual place where common prayer shall be used – on Sundays and holy days – upon penalty of forfeiting, for every non-attendance, twelve pence, to be levied by the Churchwardens to the use of the poor.” The enactments regarding holy days were allowed to be disregarded. In the reign of James I., the penalty of a shilling for not attending church on Sunday was re-enforced. Sunday, only in respect of the attendance at church, is named in the statutes of William and Mary and George III., by which exceptions in favour of dissenters from the Church of England were made. Not a few suits were commenced against persons for not attending church. An early case is noted in the church book of St. James’s, Bristol. On July 6th, 1598, Henry Anstey, a resident in that parish, had, in answer to a summons, to appear before the vestry for not attending the church. At Kingston-on-Thames, we gather from the parish accounts that the local authorities, in 1635, “Received from idle persons, being from the church on Sabbaths, 3s. 10d.” Some more recent cases are named by Professor Amos, in his Treatise on Sir Matthew Hale’s “History of the Pleas of the Crown.” In the year 1817, it is stated that, “at the Spring Assizes of Bedford, Sir Montague Burgoyne was prosecuted for having been absent from church for several months; when the case was defeated by proof of the defendant being indisposed. And in the Report of the Prison Inspectors to the House of Lords, in 1841, it appeared that, in 1830, ten persons were in prison for recusancy in not attending their parish churches. A mother was prosecuted by her own son. It is clear that, in many instances, personal and not religious feeling gave rise to the actions.” The laws respecting recusants were repealed in the year 1844.

The Easter Sepulchre

Several of our old churches contain curious stone structures called Easter Sepulchres. They are generally on the north side of the chancel, and resemble, in design, a tomb. Before the Reformation, it was the practice on the evening of Good Friday, to place the Crucifix and Host in these sepulchres with much ceremony. Numerous candles were lighted, and watchers stood by until the dawn of Easter Day. Then, with every sign of devotion, the Crucifix and Host were once more removed to the altar, and the church re-echoed with joyous praise.

Concerning this ceremony, Cranmer says that it was done “In remembrance of Christ’s sepulture, which was prophesied by Esaias to be glorious, and to signify there was buried the pure and undefiled body of Christ, without spot of sin, which was never separated from the Godhead, and, therefore, as David expressed it in the fifteenth Psalm, it could not see corruption, nor death detain or hold Him, but, He should rise again, to our great hope and comfort; and, therefore, the church adorns it with lights to express the great joy they have of that glorious triumph over death, the devil, and hell.”

We have adverted to Easter Sepulchres of stone remaining at the present time, but they were by no means the only description erected. The Rev. Mackenzie E. C. Walcott, in his “Sacred Archæology,” names, as follow, five sorts of sepulchres. The first, a chapel, as at Winchester; second, a wall recess, usually in the north side of the chancel, as at Bottesford, Lincolnshire, and Stanton St. John; third, a temporary structure, sumptuously enriched, as at St. Mary, Redcliffe, Bristol; fourth, a tomb, under which a founder, by special privilege, was buried; fifth, a vaulted enclosure, as at Norwich, which, like a sepulchre at Northwold, has an aperture for watching the light, without requiring the person so employed to enter the choir.

There was an imposing example at Seville, raised over the tomb of Columbus. It was constructed of wood, and was three storeys high, and brilliantly lighted. According to an old poet:

“With tapers all the people come, and at the barriars stay,Where downe upon their knees they fall, and night and day they pray,And violets and every kinde of flowers about the graveThey straw, and bring all their giftes and presents that they have.”We are told that in many places, the steps of the sepulchre were covered with black cloth. Soldiers in armour, keeping guard, rendered the ceremony impressive. A gentleman named Roger Martin, who lived at the time of the Reformation, wrote an interesting account of the church of Melford, Suffolk. The following particulars are drawn from his manuscript respecting the Easter Sepulchre: “In the quire, there was a fair painted frame of timber, to be set up about Maunday Thursday, with holes for a number of fair tapers to stand in before the sepulchre, and to be lighted in the service time. Sometimes, it was set overthwart the quire, before the high altar, the sepulchre being alwaies placed, and finely garnished, at the north end of high altar, between that and Mr. Clopton’s little chapel there, in a vacant place of the wall, I think upon a tomb of one of his ancestors, the said frame with the tapers was set near to the steps going up to the said altar.” The tomb referred to is that of John Clopton, Esquire, of Kentwell Hall, who filled the office of Sheriff of the county of Suffolk in the year 1451, and died in 1497. An inventory of church goods belonging to Melford Church, under date of April 6th, 1541, has a statement to the effect that “There was given to the church of Melford, two stained cloths, whereof the one hangeth towards Mr. Martin’s ile, and the other to be used about the sepulchre at Easter time.”

In a curious work entitled “The Ancient Rites and Monuments of the Monastical and Cathedral Church of Durham,” collected from out of ancient manuscripts about the time of the suppression, and published by J. D. (Davies), of Kidwelly, in 1672, there is an interesting account of a custom enacted at Durham. The following account is supposed to have been written in 1593, and, perhaps, by one who took part in the ceremonies, at all events, the writer was conversant with them. “Within the Church of Durham, upon Good Friday, there was a marvellous solemn service, in which service time, after the Passion was sung, two of the ancient monks took a goodly large crucifix, all of gold, of the picture of our Saviour Christ, nayled upon the cross… The service being ended, the said two monks carried the cross to the sepulchre with great reverence, which sepulchre was set up in the morning on the north side of the quire, nigh the high altar, before the service time, and they did lay it within the said sepulchre with great devotion, with another picture of our Saviour Christ, in whose Breast they did enclose, with great reverence, the most holy and blessed Sacrament of the Altar, censing and praying unto it upon their knees, a great space; and setting two lighted tapers before it, which did burn till Easter Day in the morning, at which time it was taken forth… There was very solemn service betwixt three and four of the clock in the morning, in honour of the Resurrection, where two of the eldest monks in the quire came to the sepulchre, set up upon Good Fryday, after the Passion, all covered with red velvet embroider’d with gold, and did then cense it, either of the monks with a pair of silver censers, sitting on their knees before the sepulchre. Then they, both rising, came to the sepulchre, out of which, with great reverence, they took a marvellous beautiful image of our Saviour, representing the Resurrection, with a cross in his hand, on the breast was enclosed, in most bright chrystal, the holy Sacrament of the Altar, through which chrystal, the Blessed Host was conspicious to the beholders. Then, after the elevation of the said picture, carried by the said two monks, upon a fair velvet cushion, all embroider’d, singing the anthems of Christus Resurgens, they brought it to the high altar.” We gather from the preceding and other accounts, that the sepulchre at Durham was a temporary erection, consisting of a wooden framework, having silk hangings.

As might be expected, much interesting information may be found in old churchwardens’ accounts bearing on this theme. The records of St. Mary Redcliffe Church, Bristol, contain the following entries:

“Item – That Maister Canynge hath delivered, this 4th day of July, in the year of Our Lord 1470, to Maister Nicholas Petters, vicar of St. Mary Redcliffe, Moses Conterin, Philip Bartholomew, Procurators of St. Mary Redcliffe aforesaid, a new sepulchre, well gilt with golde, and a civer thereto.

Item – An image of God Almighty rising out of the same sepulchre, with all the ordinance that longeth thereto; that is to say, a lathe made of timber, and the ironwork thereto.

Item – Thereto longeth Heaven, made of timber and stayned clothes.

Item – Hell, made of timber, and the ironwork thereto, with Divels to the number of 13.

Item – 4 Knights, armed, keeping the sepulchre, with their weapons in their hands; that is to say, 2 axes and 2 spears, with 2 paves. [A pave was a shield.]

Item – 4 payr of Angels wings for 4 Angels, made of timber, and well painted.

Item – The Fadre [i. e., the Father], the Crowne and Visage, the ball with a cross upon it, well gilt with fine gould.

Item – The Holy Ghost coming out of Heaven into the sepulchre.

Item – Longeth to the 4 Angels 4 Chevelures.”

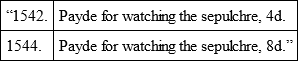

We cull from the accounts of St. Helen’s, Abingdon, Berkshire, some quaint items as follows:

In this case, of course, the sepulchre was merely a temporary erection. In the churchwardens’ accounts of Waltham Abbey Church are the following entries:

Amongst the churches of this country where permanent Easter Sepulchres still remain, are the following: Heckington, Navenby, Northwold, Holcombe, Burnell, Southpool, Hawton, and Patrington. We give an illustration of the interesting example at Patrington, East Yorkshire. Mr. Bloxham speaks of it as probably the work of the earlier years of the fifteenth century. The carvings are of freestone, and represent the watching of three soldiers, beneath three ogee-shaped canopies. On their shields are heraldic designs. The other figures represent our Saviour, emerging from the tomb, and two angels are raising the lid of the coffin. This is certainly a very interesting example, but perhaps not so fine as those of Navenby and Heckington, Lincolnshire.