полная версия

полная версияOld Church Lore

Kissing the Bride

The parents of a bride in humble circumstances rarely attend the marriage ceremony at the church. The father’s place is usually filled by one of the bridegroom’s friends. He, in some parts of the North of England, claims the privilege of first kissing the newly-made wife, in right of his temporary paternity. Some of the old-fashioned clergy regarded the prerogative as theirs, and were by no means slow in exercising it. As soon as the ceremony was completed they never failed to quickly kiss the bride. Even a shy and retiring vicar would not neglect the pleasant duty. The Rev. Thomas Ebdon, vicar of Merrington, who was deemed the most bashful of men, always kissed the women he married.

It is related of a priest, who was a stranger to the manners and customs of the Yorkshire folk, that, after marrying a couple, he was surprised to see the party still standing as if something more was expected. He at last asked why they were waiting. “Please, sir,” said the bridegroom, “ye’ve no kissed Molly.”

Mr. William Henderson, in his “Folk-Lore of the Northern Counties,” a work drawn upon for these statements, says that he can “testify that, within the last ten years, a fair lady, from the county of Durham, who was married in the south of England, so undoubtedly reckoned upon the clerical salute that, after waiting in vain, she boldly took the initiative, and bestowed a kiss on the much-amazed south-country vicar.” Mr. Henderson’s work was published in 1879.

According to the “Folk-Lore of the West of Scotland,” by James Napier, published in 1879, the kissing custom was practised in that country. “As soon as the ceremony was concluded,” says Mr. Napier, “there was a rush on the part of young men to get the first kiss of the newly-made wife. This was frequently taken by the clergyman himself, a survival of an old custom said to have been practised in the middle ages.” In an old song, the bridegroom thus addresses the minister:

“It’s no very decent for you to be kissing,It does not look well wi’ the black coat ava’,’Twould hae set you far better tae gi’en us your blessing,Than thus by such tricks to be breaking the law.Dear Watty, quo’ Robin, it’s just an auld custom,And the thing that is common should ne’er be ill taen,For where ye are wrong, if ye hadna a wished him,You should have been first. It’s yoursel it’s to blame.”This custom appears to have been very general in past times, and Mr. Henderson suggests that “it may possibly be a dim memorial of the osculum pacis, or the presentation of the Pax to the newly-married pair.”

It was formerly customary in Ireland for the priest to conclude the marriage ceremony by saying, “kiss your wife.” Instructions more easily given than performed, for other members of the party did their utmost to give the first salute.

In England, a kiss was the established fee for a lady’s partner after the dance was finished. In a “Dialouge between Custom and Veirtie concerning the Use and Abuse of Dancing and Minstrelsie,” the following appears:

“But some reply, what foole would daunce,If that when daunce is dooneHe may not have at ladye’s lipsThat which in daunce he woon?”The following line occurs in the Tempest:

“Curtsied when you have and kissed.”In Henry VIII., says the prince:

“I were unmannerly to take you out,And not to kiss you.”Numerous other references to kissing are contained in the plays of Shakespeare. From his works and other sources we find that kissing was general in the country in the olden time. It is related of Sir William Cavendish, the biographer of Cardinal Wolsey, that, when he visited a French nobleman at his chateau, his hostess, on entering the room with her train of attendant maidens, for the purpose of welcoming the visitor, thus accosted him:

“Forasmuch as ye be an Englishman, whose custom it is in your country to kiss all ladies and gentlemen without offence, it is not so in this realm, yet will I be so bold as to kiss you, and so shall all my maidens.”

It is further stated how Cavendish was delighted to salute the fair hostess and her many merry maidens.

Hot Ale at Weddings

In the year 1891, a paragraph went the rounds of the north-country newspapers respecting the maintaining of an old wedding custom at Whitburn parish church, near Sunderland. From the days of old to the present time, it has been the practice of sending to the church porch, when a marriage is being solemnised, jugs of spiced ale, locally known as “hot pots.”

A Whitburn gentleman supplied Mr. Henderson with particulars of his wedding, for insertion in “Folk-Lore of the Northern Counties” (London, 1879). “After the vestry scene,” says the correspondent, “the bridal party having formed a procession for leaving the church, we were stopped at the porch by a row of five or six women, ranged to our left hand, each holding a large mug with a cloth over it. These were in turn presented to me, and handed by me to my wife, who, after taking a sip, returned it to me. It was then passed to the next couple, and so on in the same form to all the party. The composition in these mugs was mostly, I am sorry to say, simply horrible; one or two were very fair, one very good. They are sent to the church by all classes, and are considered a great compliment. I have never heard of this custom elsewhere. Here, it has existed beyond the memory of the oldest inhabitant, and an aged fisherwoman, who has been married some sixty-five years, tells me at her wedding there were seventy hot pots.”

Drinking wine and ale at church weddings is by no means a local custom, as suggested by Mr. Henderson’s correspondent. Brand, in his “Popular Antiquities,” and other writers, refer to the subject. On drinking wine in church at marriages, says Brand, “the custom is enjoined in the Hereford Missal. By the Sarum Missal it is directed that the sops immersed in this wine, as well as the liquor itself, and the cup that contained it, should be blessed by the priest. The beverage used on this occasion was to be drunk by the bride and bridegroom and the rest of the company.” It appears that pieces of cake or wafers were immersed in the wine, hence the allusions to sops.

Many of the older poets refer to the practice. In the works of John Heywood, “newlie imprinted 1576,” is a passage as follows:

“The drinke of my brydecup I should have forborne,Till temperaunce had tempred the taste beforne.I see now, and shall see, while I am alive,Who wedth or he be wise shall die or he thrive.”In the “Compleat Vintner,” 1720, it is asked:

“What priest can join two lovers’ hands,But wine must seal the marriage bands?As if celestial wine was thoughtEssential to the sacred knot,And that each bridegroom and his brideBeliev’d they were not firmly ty’dTill Bacchus, with his bleeding tun,Had finished what the priest begun.”Old plays contain allusions to this custom. We read in Dekker’s “Satiro-Mastix”: “And, when we are at church, bring the wine and cakes.” Beaumont and Fletcher, in the “Scornful Lady,” say:

“If my wedding-smock were on,Were the gloves bought and given, the licence come,Were the rosemary branches dipt, and allThe hippocras and cakes eat and drunk off.”At the magnificent marriage of Queen Mary and Philip, in Winchester Cathedral, in 1554, we are told that, “The trumpets sounded, and they both returned, hand in hand, to their traverses in the quire, and there remained until mass was done, at which time wyne and sopes were hallowed, and delivered to them both.”

Numerous other notes similar to the foregoing might be reproduced from old writers, but sufficient have been cited to show how general was the custom in bygone times. The Rev. W. Carr, in his “Glossary of the Craven Dialect,” gives us an illustration of it lingering in another form in the present century. In his definition of Bride-ale, he observes that after the ceremony was concluded at the church, there took place either a foot or horse race, the first to arrive at the dwelling of the bride, “requested to be shown to the chamber of the newly-married pair, then, after he had turned down the bed-clothes, he returns, carrying in his hand a tankard of warm ale, previously prepared, to meet the bride, to whom he triumphantly offers the humble beverage.” The bride, in return for this, presents to him a ribbon as his reward.

Marrying Children

The marriage of children forms a curious feature in old English life. In the days of yore, to use the words of a well-informed writer on this theme, “babes were often mated in the cradle, ringed in the nursery, and brought to the church porch with lollipops in their mouths.” Parents and guardians frequently had joined together in matrimony young couples, without any regard for their feelings. Down to the days of James I., the disposal in marriage of young orphan heiresses was in the hands of the reigning monarchs, and they usually arranged to wed them to the sons of their favourites, by whom unions with wealthy girls were welcomed.

Edward I. favoured early marriages, and his ninth daughter, Eleanor, was only four days old, it is stated on good authority, “when her father arranged to espouse her to the son and heir of Otho, late Earl of Burgundy and Artois, a child in custody of his mother, the Duchess of Burgundy.” Before she had reached the age of a year, the little princess was a spouse, but, dying in her sixth year, she did not attain the position of wife planned for her.

Careful consideration is paid to early marriages in an able work by the late Rev. W. Denton, M.A., entitled “England in the Fifteenth Century” (London, 1888.) Mr. Denton says that the youthful marriages “probably originated in the desire of anticipating the Crown in its claim to the wardship of minors, and the disposal of them in marriage. As deaths were early in those days, and wardship frequent, a father sought by the early marriage of his son or daughter to dispose of their hands in his lifetime, instead of leaving them to be dealt out to hungry courtiers, who only sought to make a large profit, as they could, from the marriage of wards they had bought for the purpose. Fourteen was a usual period for the marriage of the children of those who would save their lands from the exactions of the Crown.” He adverts to marriages at an earlier age, and even paternity at fourteen.

In 1583 was published a work entitled “The Anatomie of Abuses,” by Philip Stubbes, and it supplies a curious account of the amusements and other social customs of the day. Marriage comes in for attention, and, after referring to it with words of commendation, he adds: “There is permitted one great liberty therein – for little maids in swaddling clothes are often married by their ambitious parents and friends, when they know neither good nor evil, and this is the origin of much wickedness. And, besides this, you shall have a saucy boy often, fourteen, sixteen, or twenty years of age, catch up a woman without any fear of God at all.” The protests of Stubbes and others had little effect, for children continued to be married, if not mated.

The marriage of Robert, Earl of Essex, and Lady Francis Howard, was celebrated in the year 1606. The former was not fourteen, and the latter was thirteen years of age. The union was an unhappy one. The “Diary and Correspondence of John Evelyn, F.R.S.,” contains references to early marriages. He wrote, under date of August 1, 1672: “I was at the marriage of Lord Arlington’s only daughter (a sweet child if ever there was any) to the Duke of Grafton the king’s natural son by the Duchess of Cleveland; the Archbishop of Canterbury officiating, the king and all the grandees being present.” The little girl at this time was only five years of age. Evelyn concludes his entry by saying, “I had a favour given to me by my lady; but took no great joy at the thing for many reasons.” Seven years later, the children were re-married, and Evelyn, in his “Diary,” on November 6th, 1679, states that he attended the re-marriage of the Duchess Grafton to the Duke, she being now twelve years old. The ceremony was performed by the Bishop of Rochester. The king was at the wedding. “A sudden and unexpected thing,” writes Evelyn, “when everybody believed the first marriage would have come to nothing; but the measure being determined, I was privately invited by my lady, her mother, to be present. I confess I could give her little joy, and so I plainly told her, but she said the king would have it so, and there was no going back.” The diarist speaks warmly of the charms and virtues of the young bride; and he deplores that she was sacrificed to a boy that had been rudely bred.

As might be expected, the facile pen of Samuel Pepys, the most genial of gossipers, furnishes a few facts on this subject. His notes occur in a letter, dated September 20, 1695, addressed to Mrs. Steward. It appears from his epistle that two wealthy citizens had recently died and left their estates, one to a Blue-coat boy and the other to a Blue-coat girl, in Christ’s Hospital. The circumstance led some of the magistrates to bring about a match with the youthful pair. The wedding was a public one, and was quite an event in London life. Pepys says, the boy, “in his habit of blue satin, led by two of the girls, and she in blue, with an apron green, and petticoat yellow, all of sarsnet, led by two of the boys of the house through Cheapside to Guildhall Chapel, where they were married by the Dean of St. Paul’s.” The Lord Mayor gave away the bride.

The marriage of Charles, second Duke of Richmond, and Lady Sarah Cadogan, daughter of the first Earl of Cadogan, forms an extremely romantic story. It is said that it was brought about to cancel a gambling debt between their parents. The youthful bridegroom was a student at college, and the bride a girl of thirteen, still in the nursery. The young Lord of March protested against the match, saying “surely you are not going to marry me to that dowdy.” His protestations were in vain, for the marriage service was gone through, and the twain were made one. They parted after the ceremony, and the young husband spent three years in foreign travel, doubtless thinking little about his wife. At all events on his return he did not go direct to her, but visited the sights in town. On his first attendance at the theatre, a most beautiful lady attracted his attention. He inquired her name, and to his surprise he was told that she was Lady March. The young lord hastened to claim his wife, and they spent together a happy life.

In the reign of William III., George Downing, at the age of fifteen, married a Mary Forester, a girl of thirteen. As soon as the marriage service had been concluded, the pair parted company, the boy going abroad to finish his education, and the girl returning home to resume her studies. After spending some three or four years on the Continent, the husband returned to England, and was entreated to live with his wife. He declined to even see her, having a great aversion to her. The husband’s conduct caused his wife to entertain feelings of hatred of him, and both would have been glad to have been freed from a marriage contracted before either were master of their own actions, but they sued in vain for a divorce.

The editor of the “Annual Register,” under date of June 8th, 1721, chronicles the marriage of Charles Powel, of Carmarthen, aged about eleven years, to a daughter of Sir Thomas Powel, aged about fourteen. Four years later, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, in one of her lively letters, refers to the marriage, in 1725, of the Duke of Bedford, at the age of sixteen years.

The General Assembly of Scotland, in 1600, ruled that no minister should unite in matrimony any male under fourteen and any female under twelve years of age. The regulation was not always obeyed. In 1659, for example, Mary, Countess of Buccleuch, in her eleventh year, was married to Walter Scott, of Highchester, and his age was fourteen. As late as the 1st June, 1859, was married, at 15, St. James’ Square, Edinburgh, a girl in her eleventh year. The official inspector, when he saw the return, suspected an error, but, on investigation, found it was correct.

Young men and maidens may congratulate themselves on living in these later times, when they may not be united in wedlock before they are old enough to think and act for themselves.

The Passing Bell

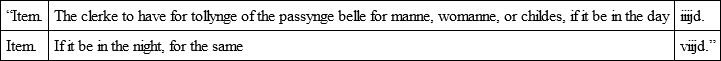

The passing bell, or soul bell, rang whilst persons were passing from this life to that beyond, and it was rung that all who heard it might address prayers to heaven and the saints for the soul then being separated from the mortal body. One of the earliest accounts of the use of bells in England is connected with this bell. Bede, in speaking of the death of the Abbess of St. Hilda, says that a sister in a distant monastery thought that she heard in her sleep the well-known sound of the passing bell. She no sooner heard it than she called all the sisters from their rest into the church, where they prayed and sang a requiem. To show how persistently the custom was maintained, we may quote from the “Advertisements for due Order,” passed in the seventh year of the reign of Queen Elizabeth: “Item, that when anye Christian body is in passing, that the bell be tolled, and that the curate be speciallie called for to comforte the sicke person; and, after the time of his passinge, to ringe no more, but one shorte peale, and one before the buriall, and another shorte peale after the buriall.” In ancient days, the bell rang at the hour of passing, whether it happened to be night or day. In the churchwardens’ accounts for the parish of Wolchurch, 1526, appears the following regulation:

Shakespeare’s universal observation led him to make use of the melancholy meaning of the death bell. He says, in the second part of King Henry IV.:

“And his tongueSounds ever after as a sullen bellRemembered knolling a departing friend.”The passing bell has a place in the story of the death, in the Tower of London, of Lady Catherine Grey, sister to the unfortunate Lady Jane. The constable of the Tower, Sir Owen Hopton, seeing that the end was approaching, said to Mr. Bokeham: “Were it not best to send to the church, that the bell may be rung?” and Lady Catherine herself, hearing the remark, said to him: “Good Sir Owen, be it so,” and died almost at once, closing her eyes with her own hands. This was in 1567.

The tolling of the passing bell, as such, continued until the time of Charles II., and it was one of the subjects of inquiry in all articles of visitation.

The form of inquiry in the Archdeaconry of Yorke by the churchwardens and swornemen, in 163-, was: “Whether doth your clark or sexton, when any one is passing out of this life, neglect to toll a bell, having notice thereof, or, the party being dead, doth he suffer any more ringing than one short peale, and before his burial one, and after the same another?” Inquiry was also to be made: “Whether, at the death of any, there be any superstitious ringing?” There is a widespread saying:

“When the bell begins to toll,Lord have mercy on the soul.”Gascoigne, in his “Workes,” 1587, mentions the passing bell in the prefatory lines to a sonnet, he says:

“Alas, loe now I heare the passing bell,Which care appoynteth carefully to knowle,And in my brest I feele my heart now swellTo breake the stringes which joynd it to my soule.”Another instance of the poetic use is to be found in the Rape of Lucrece, by Heywood (1630), where Valerius exclaims: “Nay, if he be dying, as I could wish he were, I’le ring out his funerall peale, and this it is:

Come list and harke, the bell doth towle,For some but now departing soule.And was not that some ominous fowle,The batt, the night-crow, or skreech-owle,To these I heare the wild woolfe howle,In this black night that seems to skowle.All these my black booke shall in-rowle;For hark, still, still, the bell doth towleFor some but now departing sowle.”Just a little earlier, Copley, in his “Wits, Fits, and Fancies” (1614), bears evidence to the ringing of the bell while persons were yet alive. A gentleman who lay upon a severe sick bed, heard a passing bell ring out, and thereupon asked his physician: “Tell me, maister Doctor, is yonder musicke for my dancing?” Continuing the subject, he gives an anecdote concerning “The ringing out at the burial.” It is as follows: A rich miser and a beggar were buried in the same churchyard at the same time, “and the belles rung out amaine” for the rich man. The son of the former, fearing the tolling might be thought to be for the beggar instead of his father, hired a trumpeter to stand “all the ringing-while” in the belfry and proclaim between every peal, “Sirres, this next peale is not for R., but for Maister N.,” his father. In the superstitions which gathered round the bells of Christianity, the passing bell was considered to ward off the influence of evil spirits from the departing soul. Grose says: “The passing bell was anciently rung for two purposes: one to bespeak the prayers of all good Christians for a soul just departing; the other to drive away the evil spirits who stood at the bed’s foot and about the house, ready to seize their prey, or at least to molest and terrify the soul in its passage; but, by the ringing of the bell (for Durandus informs us evil spirits are much afraid of bells), they were kept aloof; and the soul, like a hunted hare, gained the start, or had what is by sportsmen called law. Hence, perhaps, exclusive of the additional labour, was occasioned the high price demanded for tolling the greatest bell of the church, for, that being louder, the evil spirits must go farther off to be clear of its sound, by which the poor soul got so much more the start of them; besides, being heard farther off, it would likewise procure the dying man a greater number of prayers.” This dislike of spirits to bells is mentioned in the “Golden Legend,” by Wynkyn de Worde.

Douce takes the driving away of the spirits to be the main object in ringing the passing bell, and draws attention to the woodcuts in the Horæ, which contain the “Service of Dead,” where several devils are represented as waiting in the chamber of the dying man, while the priest is administering extreme unction. Of course, the interpretation that the spirits are waiting to take possession of the soul so soon as disembodied is not necessarily the intentional meaning. Douce concludes his remarks by an observation which has escaped the notice of most of those who have dealt with the subject. He says: “It is to be hoped that this ridiculous custom will never be revived, which has been most probably the cause of sending many a good soul to the other world before its time; nor can the practice of tolling bells for the dead be defended upon any principle of common sense, prayers for the dead being contrary to the articles of our religion.” When the English first began to see the apparent inconsistency of the practice of tolling with their declared religion, the subject gave rise to much controversy. The custom had many apologists. Bishop Hall says: “We call them soul bells, for that they signify the departure of the soul, not for that they help the passage of the soul.” Wheatly says: “Our Church, in imitation of the saints in former ages, calls on the minister and others who are at hand to assist their brother in his last extremity.” Dr. Zouch (1796) says: “The soul bell was tolled before the departure of a person out of life, as a signal for good men to offer up their prayers for the dying. Hence the abuse commenced of praying for the dead.” He cites Douce’s versified letter to Sir Henry Wotton:

“And thicken on you now, as prayers ascendTo heaven on troops at a good man’s passing bell.”Fuller, long before this, in 1647, expresses some little indignation at hearing a bell toll after the person had died, as he was thereby cheated into prayer. He observes: “What is this but giving a false alarm to men’s devotions, to make them ready to arm with their prayers for the assistance of such who have already fought the good fight.” Dekker, in an evident reference to the passing bell, calls it “the great capon-bell.”

From the number of strokes being formerly regulated according to circumstances, the hearers might determine the sex and social condition of the dying or dead person. Thus the bell was tolled twice for a woman and thrice for a man. If for a clergyman, as many times as he had orders, and, at the conclusion, a peal on all the bells to distinguish the quality of the person for whom the people are to put up their prayers. In the North of England, are yet rung nine knells for a man, six for a woman, and three for a child.