полная версия

полная версияOld Church Lore

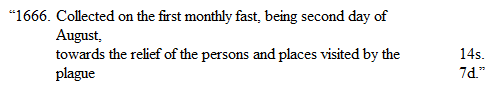

Collections in churches were very general for those suffering from the plague. The following entry, reproduced from the parish register of the small town of Cheadle, Staffordshire, may be quoted as a specimen of similar records:

The plague penetrated into most unexpected places. Far away from London, in the Peak of Derbyshire, is the delightfully-situated mountain village of Eyam, a place swept over by health-giving breezes. It is a locality of apparent security against infection. In September, 1665, a parcel of tailor’s patterns was sent from London to Eyam, and with it came the disease. At that time the village had a population of 350 persons, and when the plague “was exhausted with excessive slaughter,” only seventy-three were alive. From September 6th, 1665, to October 11th, 1666, 277 died, the death rate being much higher than that of London. The history of this visitation is heart-rending, and has been told by several writers, but by none more carefully than by William Wood, in his “History of Eyam,” published by Richard Keene, of Derby. Two names in this dark story stand out in bright relief, one was the Rev. Thomas Stanley, the ejected rector of the parish, in 1662, and the Rev. William Mompesson, a successor, who was appointed in 1664. With their lives in their hands, these two brave men remained at the post of duty, visited, advised, and aided the sufferers unto death. Mrs. Mompesson administered daily to her husband’s suffering parishioners until death closed her useful life, on the 24th August, 1666. This was a terrible blow to her devoted husband, and a heavy loss to the villagers. “At one time,” we are told, “Mrs. Mompesson’s heart failed her, when she thought of her two children in the midst of the plague. She cast herself and her two children at the feet of her husband, and begged that they might all depart from the death-stricken place. In the most loving manner, however, he raised her from his feet, and pointed out the awful responsibility which would attach to his deserting his post. He then besought his wife to flee to some distant spot, where she and her babes might be safe. She refused, however, to leave him, but they mutually agreed to send the children to a relative in Yorkshire.”

About the middle of June, the more wealthy people fled to distant places from the plague-stricken village, and others built huts on the neighbouring hills, and in them took shelter. The entire population appeared determined to flee. Mr. Mompesson pointed out the folly of such a proceeding, observing that they would carry the disease to other places. His earnest entreaties prevailed.

He wrote to the Earl of Devonshire for assistance, to enable the inhabitants to remain in their own village. The Earl realised the importance of confining the disease within a certain limit. He readily made arrangements for a constant supply of food and clothing for the sufferers. A boundary was fixed round the village, marked by stones, and the residents solemnly agreed that not one should go beyond the radius indicated. The provisions, etc., were left early in the morning at an appointed place, and were fetched away by men selected for the work. If money was paid, it was placed in water. The men of Eyam faithfully kept their promise, so that the plague was not carried by them to any other places.

The churchyard was closed and funeral rites were not read; graves were made in fields and gardens near the cottages of the departed.

During the time the disease was at its height, the church was closed but the faithful rector did not neglect to assemble his flock each succeeding Sabbath in a quiet spot on the south side of the village, and to proclaim to them words of comfort.

Shortly after the disease had stopped at Eyam, the rectory of Eaking was presented to Mr. Mompesson. The inhabitants of his new parish had such a terror of the plague that they dreaded his coming amongst them, and a hut was built for him in Rufford Park, where he remained until their fears had subsided.

This short study of a serious subject enables us to fully realise the force of the supplication in the Litany: “From Plague and Pestilence, Good Lord deliver us.”

A King Curing an Abbot of Indigestion

Many of the English monarchs have delighted in the pleasures of the chase. Their hunting expeditions have often led them into out-of-the-way places where they were unknown, and their adventures gave rise to good stories, which have done much to enliven the dry pages of national history. Bluff King Hal was a jovial huntsman, and was one day enjoying the pastime in the glades of Windsor Forest, when he missed his way, and, to his surprise, found himself near the Abbey at Reading. He keenly felt the pangs of hunger, and resolved to try and get a meal at the table of the Abbey hard by.

After disguising himself, he made his way to the house, under the pretence of being one of the king’s guards. He was invited to partake of a sirloin of beef, and he did such justice to it as to surprise not a little the worthy abbot. The latter pledged his guest’s royal master, adding that if his weak stomach could digest such a meal as his visitor had just eaten he would gladly give a hundred pounds. He lamented that he could only take for his dinner the wing of a chicken, or other equally small dainty. The burly stranger pledged him in return, and, after expressing his gratitude, departed without his identity being discovered.

After a few short weeks had passed, another stranger wended his way to the Abbey of Reading, armed with a warrant from King Henry VIII. to take the abbot a prisoner, and lodge him in the Tower. It was with a heavy heart that the abbot journeyed to London. His prison fare was very plain, and consisted of bread and water, and provided in small quantities, so that he not only suffered in mind, but also from the want of food. He often wondered what he had done to displease the king, but could not obtain any information on the subject. A change at last came over the scene. A fine sirloin of beef was placed on his table, and he was bidden to feast to his heart’s content. He did not need any pressing to do justice to the joint, for he was almost famished, and dined more like a glutton than a man with a weak stomach. The king watched with amusement, from a secret place, the abbot enjoying his dinner, and, when he had nearly completed it, stepped forth from his hiding place, and demanded one hundred pounds for curing the poor abbot of his indigestion, and reminded him of their former meeting at the Abbey of Reading. The patient gladly paid his physician the stipulated fee, and, with a light purse and a merry heart, bent his steps homeward.

The Services and Customs of Royal Oak Day

Writing in his diary, on May 29th, 1665, John Evelyn says: “This was the first anniversary appointed by Act of Parliament to be observed as a day of General Thanksgiving for the miraculous restoration of his Majesty: our vicar preaching on Psalm cxviii. 24, requiring us to be thankful and rejoice, as indeed we had cause.” A special form of prayer in commemoration of the Restoration of Charles II. was included in the Book of Common Prayer until 1859, when it was removed by Act of Parliament.

On this day, the Chaplain of the House of Commons used to preach before the House, in St. Margaret’s Church, Westminster. The service has been discontinued since 1858. It attracted little attention, and the congregation usually consisted of the Speaker, the Sergeant-at-arms, the clerks and other officers, and about half a dozen members.

It was, in bygone times, in many parts of England, the practice, on this day, to fasten boughs of oak to the pinnacles of church steeples.

The display of oak is in memory of the king’s escape after the Battle of Worcester, in 1651, and of his successfully hiding himself in an oak tree at Boscobel. Tennyson, in his “Talking Oak,” refers to the subject:

“Thy famous brother oak,Wherein the younger Charles abode,Till all the paths grew dim,While far below the Roundheads rode,And humm’d a surly hymn.”Richard Penderel greatly assisted Charles in his time of trouble, and he selected the oak in which safety was found. When Charles “came to his own,” the claims of Penderel were not overlooked. He was attached to the Court. When he died, he was buried with honours at St. Giles-in-the-Fields. It was customary, for a long period, to decorate his grave in the churchyard with oak branches.

Formerly, in Derbyshire, it was the practice to place over the doors of houses, branches of young oak, and it is still the custom for boys to wear sprigs of the same tree in their hats and buttonholes. If the lads neglect to wear the oak-leaf they are stung with nettles by their more loyal companions. At Looe, and other districts of East Cornwall, it was enforced by spitting at or “cobbing” the offender. In bygone times, the boys of Newcastle-on-Tyne had an insulting rhyme, which they used to repeat to such folk as they met who did not wear oak-leaves:

“Royal oakThe Whigs to provoke.”On this day, many wore plane tree leaves, and would make a retort to the foregoing rhyme:

“Plane tree leaves;The Church folk are thieves.”Mr. John Nicholson, in his “Folk Lore of East Yorkshire” (Hull, 1890), has an interesting note on this subject. “During the days of spring,” says Mr. Nicholson, “boys busily ‘bird-nest’ (seek nests), and lay up a store of eggs for the 29th of May, Royal Oak Day, or Mobbing Day. These eggs are expended by being thrown at other boys, but all boys who carry a sprig of Royal Oak, not dog oak, either in their cap or coat, are free from molestation. Not only wild birds’ eggs, but the eggs of hens and ducks are used to ‘mob’ (pelt) with, and the older and more unsavoury the eggs are, the better are they liked – by the thrower. The children sing:

‘The twenty-ninth of May,Royal Oak Day,If you don’t give us a holidayWe’ll all run away.’”At Castleton, Derbyshire, an old custom still lingers of making a huge garland of flowers on this day, and afterwards suspending it on the top of the principal pinnacle of the church. The late Mr. Alfred Burton saw this garland constructed in 1885, and had a drawing made of it for his volume entitled “Rush-bearing.” “The framework,” says Mr. Burton, “is of wood, thatched with straw. Interior diameter, a little over two feet, outside (when covered with flowers), over three feet six inches. In shape it somewhat resembles a bell, completely covered over with wild flowers – hyacinths, water-buttercups, buttercups, daisies, forget-me-nots, wallflowers, rhododendrons, tulips, and ornamental grasses, in rows, each composed of the same flower, which have been gathered in the neighbourhood the evening before. The top, called the ‘queen,’ is formed of garden flowers, and fits into a socket at the top of the garland. It weighs over a hundredweight, requires two men to lift it, and has occupied four men from noon till five o’clock in the afternoon to make it.”

At six in the evening, a procession is formed from a village inn, whose turn it is to take the lead in the festivities. A band of music heads the processionists, next comes the garland, which, we are told by Mr. Burton, is “borne on the head and shoulders of a man riding a horse, and wearing a red jacket. A stout handle inside, which rests on the saddle in front of him, enables him to hold it upright. It completely envelopes him to the waist, and is roomy enough to enable ale to be passed up to his mouth, of which he takes good care to have a share. His horse is led for him, and he is followed by another man on horseback, dressed as a woman, who acts the fool. These are followed by the villagers, dancing, even old people who can scarcely walk making a point of attempting to dance on this, the greatest day in the year at Castleton. After parading the village, the ‘queen’ is taken off the garland and placed in the church, the garland being hoisted with ropes to the top of the church tower, where it is placed on one of the pinnacles, and left till it has withered away, when the framework is taken down and kept for another year. The other pinnacles have branches of oak.”

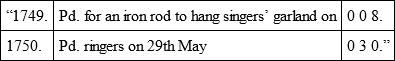

In the churchwardens’ accounts of Castleton, are entries as follows:

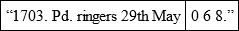

Payments for ringing bells on the 29th May occur frequently in churchwardens’ accounts, and a few examples may be quoted. The first is from Wellington, Somerset:

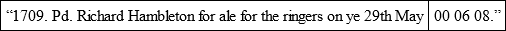

The accounts of St. Michael’s, Bishop Stortford, state:

St. Mary’s, Stamford, contain an item as follows:

Northampton is loyal to the memory of Charles II. He was a benefactor to the borough, and helped the inhabitants after the great fire of 1675. In the Baptismal Register of All Saints’, Northampton, it is recorded, under September 1675, as follows: “In this month, a very lamentable fire destroyed 3 parts of our Towne and Church.” The Marriage Register says: “While the world lasts, remember September the 20th, a dreadfull fire, it consumed to ashes in a few houres, 3 parts of our Towne and Cheef Church.” The sum of £25,000 was collected by briefs and private charities towards the heavy loss sustained by the inhabitants. Charles II. gave 1000 tons of timber out of Whittlewood forest, and remitted the duty of chimney-money in the town for seven years. We gather from Hume, that “the king’s debts had become so intolerable, that the commons were constrained to vote him an extraordinary supply of £1,200,000, to be levied by eighteen months’ assessment, and, finding upon inquiry that the several branches of the revenue fell much short of the sums they expected, they at last, after much delay, voted a new imposition of 2s. on each hearth, and this tax they settled on the king during his life.”

Macaulay speaks of this tax as being “peculiarly odious, for it could only be levied by means of domiciliary visits… The poorer householders were frequently unable to pay their hearth-money to the day. When this happened, their furniture was distrained without mercy, for the tax was farmed, and a farmer of taxes, is, of all creditors, proverbially, the most rapacious.” He quotes from some doggerel ballads of the period, and the following is one of the verses reproduced:

“The good old dames, whenever they the chimney-man espied,Unto their nooks they haste away, their pots and pipkins hide;There is not one old dame in ten, and search the nation through,But, if you talk of chimney-men, will spare a curse or two.”A reference to chimney-money occurs in an epitaph in Folkestone churchyard. Here is a copy:

“In Memory of

Rebecca Rogers,

who died August 22nd, 1688.

Aged 44 years.

A house she hath; it’s made of such good fashion,

The tenant ne’er shall pay for reparation,

Nor will her landlord ever raise her rent,

Or turn her out of doors for non-payment.

From chimney-money too this cell is free —

To such a house, who would not tenant be?”

The inhabitants of Northampton, to show their gratitude to the king for his consideration, displayed oak branches over their house doors. The members of the corporation, accompanied by the children of the charity schools, attend service at All Saints’ Church. A statue of the king, in front of the church, is usually enveloped in oak boughs on May 29th.

Marrying in a White Sheet

It was not an uncommon circumstance in the last, and even in the early years of the present century, for marriages to be performed en chemise, or in a white sheet. It was an old belief, that a man marrying a woman in debt, if he received her at the hands of the minister clothed only in her shift, was not liable to pay the accounts she had contracted before their union. We think it will not be without interest to give a few authenticated instances of this class of marriages.

The earliest example we have found, is recorded in the parish register of Chiltern, All Saints’, Wilts. It is stated: “John Bridmore and Anne Selwood were married October 17th, 1714. The aforesaid Anne Selwood was married in her smock, without any clothes or headgier on.”

On June 25th, 1738, George Walker, a linen weaver, and Mary Gee, of the “George and Dragon,” Gorton Green, were made man and wife, at the ancient chapel close by. The bride was only attired in her shift.

Particulars of another local case are given in the columns of Harrop’s Manchester Mercury, for March 12th, 1771, as follows: “On Thursday last, was married, at Ashton-under-Lyne, Nathaniel Eller to the widow Hibbert, both upwards of fifty years of age; the widow had only her shift on, with her hair tied behind with horse hair, as a means to free them both from any obligation of paying her former husband’s debts.”

We have heard of a case where the vicar declined to marry a couple on account of the woman presenting herself in her under garment. Another clergyman, after carefully reading the rubric, and not finding anything about the bride’s dress, married a pair, although the woman wore only her chemise.

The following is taken from Aris’s Birmingham Gazette for 1797:

“There is an opinion generally prevalent in Staffordshire that if a woman should marry a man in distressed circumstances, none of his creditors can touch her property if she should be in puris naturalibus while the ceremony is performed. In consequence of this prejudice, a woman of some property lately came with her intended husband into the vestry of the great church of Birmingham, and the moment she understood the priest was ready at the altar, she threw off a large cloak, and in the exact state of Eve in Paradise, walked deliberately to the spot, and remained in that state till the ceremony was ended. This circumstance has naturally excited much noise in the neighbourhood, and various opinions prevail respecting the conduct of the clergyman. Some vehemently condemn him as having given sanction to an act of indecency; and others think, as nothing is said relative to dress in the nuptial ceremony, that he had no power to refuse the rite. Our readers may be assured of this extraordinary event, however improbable it may appear in these times of virtue and decorum.”

We gather from a periodical called The Athenian, that this custom was practised in Yorkshire at the beginning of this century: “May, 1808. At Otley, in Yorkshire, Mr. George Rastrick, of Hawkesworth, aged 73, to Mrs. Nulton, of Burley Woodhead, aged 60. In compliance with the vulgar notion that a wife being married in a state of nudity exonerated her husband from legal obligations to discharge any demands on her purse, the bride disrobed herself at the altar, and stood shivering in her chemise while the marriage ceremony was performed.”

In Lincolnshire, at so late a period as between 1838 and 1844, a woman was wed enveloped in a sheet.

A slightly different method of marriage is mentioned in Malcolm’s “Anecdotes of London.” It is stated that “a brewer’s servant, in February, 1723, to prevent his liability to the payment of the debts of a Mrs. Brittain, whom he intended to marry, the lady made her appearance at the door of St. Clement Danes habited in her shift; hence her inamorato conveyed the modest fair to a neighbouring apothecary’s, where she was completely equipped with clothing purchased by him; and in these, Mrs. Brittain changed her name in church.”

In the foregoing, it will have been observed that the marriages have been conducted en chemise for the protection of the pocket of the bridegroom. “The Annual Register,” of 1766, contains an account of a wedding of this class, for the protection of the woman. We read: “A few days ago, a handsome, well-dressed young woman came to a church in Whitehaven, to be married to a man, who was attending there with the clergyman. When she had advanced a little into the church, a nymph, her bridesmaid, began to undress her, and, by degrees, stript her to her shift; thus she was led, blooming and unadorned, to the altar, where the marriage ceremony was performed. It seems this droll wedding was occasioned by an embarrassment in the affairs of the intended husband, upon which account the girl was advised to do this, that he might be entitled to no other marriage portion than her smock.”

Marrying under the Gallows

Some of the old ballads of merry England contain allusions to a law or usage of primitive times, to the effect that if a man or woman would consent to marry, under the gallows, a person condemned to death, the criminal would escape hanging. A few criminals, however, preferred the hangman’s knot to the marriage tie, if we may believe the rude rhymes of our ancestors. In one of Pinkerton’s works may be read an old poem in which we are told of a criminal refusing marriage at the foot of the gallows. Here are a few lines from the ballad:

“There was a victim in a cart,One day for to be hanged,And his reprieve was granted,And the cart made a stand.‘Come, marry a wife and save your life,’The judge aloud did cry;‘Oh, why should I corrupt my life’The victim did reply.‘For here’s a crowd of every sort,And why should I prevent their sport!The bargain’s bad in every part,The wife’s the worst – drive on the cart?’”A poem, published in 1542, entitled the “Schole House,” contains an allusion:

“To hang or wed, both hath one home,And whether it be, I am well sureHangynge is better of the twayne —Sooner done, and shorter payne.”We read in an old ballad the story of a merchant of Chichester, who was saved execution by a loving maiden.

In the old Manx “Temporal Customary Laws,” A.D. 1577, occurs the following: “If any man take a woman by constraint, or force her against her will, if she be a wife he must suffer the law of her. If she be a maid or single woman, the deemster shall give her a rope, sword, and a ring, and she shall have her choice to hang him with the rope, cut off his head with the sword, or marry him with the ring!”

It is stated in a work published in 1680, entitled “Warning to Servants, or, the case of Margaret Clark, lately executed for firing her master’s house in Southwark.” “Since the poor maid was executed, there has been a false and malicious story published concerning her in the True Domestick Intelligence of Tuesday, March 30th. There was omitted in the confession of Mary Clark (so he falsely calls her), who was executed for firing the house of M. de la Noy, dyer in Southwark, viz., that, at her execution, there was a fellow who designed to marry her under the gallows (according to the antient laudable custome), but she, being in hopes of a reprieve, seemed unwilling; but, when the rope was about her neck, she cryed she was willing, and then the fellow’s friends dissuaded him from marrying her; so she lost her husband and life together.” To the foregoing is added, “We know of no such custome allowed by law, that any man’s offering, at a place of execution, to marry a woman condemned shall save her.”

Here is a curious paragraph bearing on this theme, drawn from Parker’s London News, for April 7th, 1725: “Nine young women dressed in white, each with a white wand in her hand, presented a petition to his Majesty (George I.) on behalf of a young man condemned at Kingston Assizes of burglary, one of them offered to marry him under the gallows in case of a reprieve.”

In a work entitled “The interesting narrative of the life of Oulandah Equians, or Gustavus Vassa, written by himself,” and published in 1789, is the following passage: “While we lay here (New York, 1784) a circumstance happened which I thought extremely singular. One day, a malefactor was to be executed on the gallows, but with the condition that if any woman, having nothing on but her shift, married a man under the gallows, his life would be saved. This extraordinary privilege was claimed; and a woman presented herself, and the marriage ceremony was performed.”