полная версия

полная версияOperas Every Child Should Know

That he was a man of the most fascinating temper cannot be doubted, when one reads his memoirs. He was without any financial judgment. He could make money, but he couldn't keep it. There is a story illustrating the dominance of his heart over his head, told in connection with an offer of patronage from the King of Prussia. At that time Mozart was Emperor Leopold's musician, and when he went to Leopold to offer his resignation and take advantage of the better arrangement which the Prussian King had offered, Leopold said urgently: "But, Mozart, you surely are not going to forsake me?" "No, of course not," Mozart answered hastily. "May it please your Majesty, I shall remain." When his friends asked him if he had not been wise enough to make some demand to his own advantage at such a time, he answered in amazement: "Why, who could do such a thing – at such a time?"

His sentiment was charming, his character fascinating. He married Constance Weber, herself a celebrated person. She was never tired of speaking and writing of her husband. It was she who told of his small, beautifully formed hands, and of his favourite amusements – playing at bowls and billiards. The latter sport, by the way, has been among the favoured amusements of many famous musicians; Paderewski is a great billiard player.

As a little child, Mozart had a father who "put him through," so to speak, he being compelled to play, and play and play, from the time he was six years old. At that age he drew the bow across his violin while standing in the custom-house at Vienna, on the way to play at Schönbrunn for the Emperor, and he charmed the officers so much that the whole Mozart family baggage was passed free of tax. While at the palace he was treated gorgeously, and among the Imperial family at that time was Marie Antoinette, then a young and gay princess. The young princesses treated little Wolfgang Mozart like a brother, and when he stumbled and fell in the drawing room, it happened to be Antoinette who picked him up. "Oh, you are good, I shall marry you!" he assured her. On that occasion the Mozart family received the sum of only forty pounds for his playing, with some additions to the family wardrobe thrown in.

Most composers have had favourite times and seasons for work – in bed, with a heap of sausages before them, or while out walking. Beethoven used to pour cold water over his hands till he soaked off the ceiling of the room below; in short, most musicians except Mozart had some surprising idiosyncrasy. He needed even no instrument when composing music. He could enjoy a game of bowls, sitting and making his MS. while the game was in progress, and leaving his work to take his turn. He was not strong, physically, and was often in poor circumstances, but wherever he was there was likely to be much excitement and gaiety. He would serenely write his music on his knee, on his table, wherever and however he chanced to be; and was most at ease when his wife was telling him all the gossip of the day while he worked. After all, that is the true artist. Erraticalness is by no means the thing that makes a man great, though he sometimes becomes great in spite of it, but for the most part it is carefully cultivated through conceit.

Mozart's burial was probably the most extraordinary commentary on fame and genius ever known. The day he was buried, it was stormy weather and all the mourners, few enough to start with, had dropped off long before the graveyard was reached. He was to be buried third class, and as there had already been two pauper funerals that day, a midwife's, and another's, Mozart's body was to be placed on top. No one was at the grave except the assistant gravedigger and his mother.

"Who is it?" the mother asked.

"A bandmaster," the hearse driver answered.

"Well, Gott! there isn't anything to be expected then. So hurry up!" Thus the greatest of musical geniuses was done with this world.

Germany has given us the greatest musicians, but she leaves other people to take care of them, to love them, and to bury them – or to leave them go "third-class."

THE MAGIC FLUTE

CHARACTERS OF THE OPERAQueen of the Night.

Pamina (Queen's daughter).

Papagena.

Three ladies of the Queen's Court.

Three Genii of the Temple.

Tamino, an Egyptian Prince.

Monostatos, a Moor in the service of Sarastro.

Sarastro, High Priest of the Temple.

Papageno, Tamina's servant.

Speaker of the Temple.

Two priests.

Two armed men.

Chorus of priests of the Temple, slaves, and attendants.

The scene is near the Temple of Isis, in Egypt.

Composer: Mozart.

ACT IOnce upon a time an adventurous Egyptian youth found himself near to the Temple of Isis. He had wandered far, had clothed himself in another habit than that worn by his people, and by the time he reached the temple he had spent his arrows, and had nothing but his useless bow left. In this predicament, he saw a monstrous serpent who made after him, and he fled. He had nothing to fight with, and was about to be caught in the serpent's fearful coils when the doors of the temple opened and three ladies ran out, each armed with a fine silver spear.

They had heard the youth's cries of distress, and had rushed out to assist him. Immediately they attacked the monster and killed it, while Tamino lay panting upon the ground. When they went to him they found him unconscious. He seemed to be a very noble and beautiful youth, whose appearance was both heroic and gentle, and they were inspired with confidence in him.

"May not this youth be able, in return for our services to him, to help us in our own troubles?" they inquired of each other; for they belonged to the court of the Queen of the Night, and that sovereign was in great sorrow. Her beautiful daughter, Pamina, had been carried away, and none had been able to discover where she was hidden. There was no one in the court who was adventurous enough to search in certain forbidden and perilous places for her.

As Tamino lay exhausted upon the ground, one of the women who had rescued him declared that she would remain to guard him – seeing he had no arrows – while the others should go and tell the Queen that they had found a valiant stranger who might help them.

At this suggestion the other two set up a great cry.

"You stay to guard the youth! Nay, I shall stay myself. Go thou and tell Her Majesty." Thereupon they all fell to quarrelling as to who should remain beside the handsome youth and who should go. Each declared openly that she could gaze upon him forever, because he was such a beauty, which would doubtless have embarrassed Tamino dreadfully if he had not been quite too tired to attend to what they said.

The upshot of it was that all three went, rather than leave any one of them to watch with him. When they had disappeared into the temple once more, Tamino half roused himself and saw the serpent lying dead beside him.

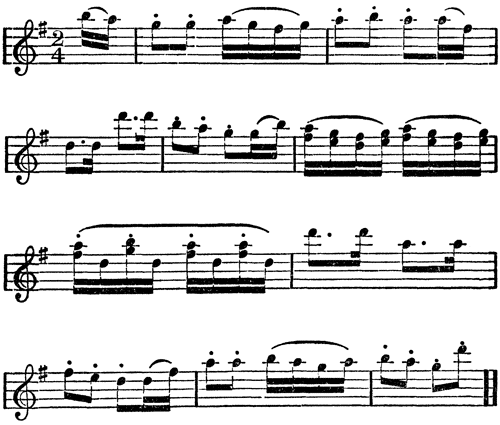

"I wonder where I can be?" he mused. "I was saved in the nick of time: I was too exhausted to run farther," and at that moment he heard a beautiful strain of music, played upon a flute:

[Listen]

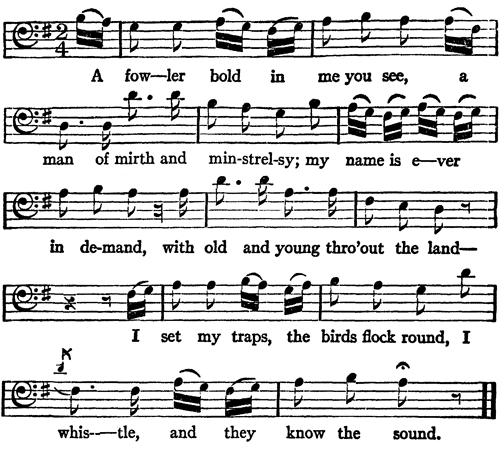

He raised himself to listen attentively, and soon he saw a man descending from among the rocks behind the temple. Still fearful of new adventures while he was unarmed and worn, Tamino rose and hid himself in the trees. The man's name was Papageno, and he carried a great cage filled with birds upon his back; in both hands he held a pipe, which was like the pipe of Pan, and it was upon this that he was making music. He also sang:

[Listen]

A fowler bold in me you see,A man of mirth and minstrelsy;My name is ever in demand,With old and young thro'out the land —I set my traps, the birds flock round,I whistle, and they know the sound.For wealth my lot I'd not resign,For every bird that flies is mine.I am a fowler, bold and free,A man of mirth and minstrelsy;My name is ever in demand,With old and young throughout the land.But nets to set for pretty maids:That were the most divine of trades.I'd keep them safe 'neath lock and key,And all I caught should be for me.

So that exceedingly jolly fellow sang as he passed Tamino. He was about to enter the temple when Tamino, seeing he had nothing to fear, stopped him.

"Hello, friend! Who are you?"

"I ask the same," the fowler answered, staring at Tamino.

"That is easily answered. I am a prince and a wanderer. My father reigns over many lands and tribes."

"Ah, ha! Perhaps in that land of thine I might do a little trade in birds," the fowler said, jovially.

"Is that how you make your living?" Tamino asked him.

"Surely! I catch birds and sell them to the Queen of the Night and her ladies."

"What does the Queen look like?" Tamino asked, somewhat curious.

"How do I know? Pray, who ever saw the Queen of the Night?"

"You say so? Then she must be the great Queen of whom my father has often spoken."

"I shouldn't wonder."

"Well, let me thank you for killing that great serpent. He nearly did for me," Tamino replied, taking it for granted that the man before him had been the one to rescue him, since he had fallen unconscious before he had seen the ladies. The fowler looked about at the dead serpent.

"Perfectly right! A single grasp of mine would kill a bigger monster than that," the fowler boasted, taking to himself the credit for the deed; but by this time the three ladies had again come from the temple and were listening to this boastful gentleman with the birds upon his back.

"Tell me, are the ladies of the court beautiful?" Tamino persisted.

"I should fancy not – since they go about with their faces covered. Beauties are not likely to hide their faces," he laughed boisterously. At that the ladies came toward him. Tamino beheld them with pleasure.

"Now give us thy birds," they said to the fowler, who became suddenly very much quieter and less boastful. He gave them the birds and received, instead of the wine he expected, according to custom, a bottle of water.

"Here, for the first time, her Majesty sends you water," said she who had handed him the bottle; and another, holding out something to him, said:

"And instead of bread she sends you a stone."

"And," said the other, "she wishes that ready mouth of yours to be decorated with this instead of the figs she generally sends," and at that she put upon his lips a golden padlock, which settled his boasting for a time. "Now indicate to this youth who killed that serpent," she continued. But the fowler could only show by his actions that he had no idea who did it.

"Very well; then, dear youth, let me tell you that you owe your life to us." Tamino was ready to throw himself at the feet of such beautiful champions, but one of them interrupted his raptures by giving him a miniature set in jewels.

"Look well at this: our gracious Queen has sent it to you."

Tamino gazed long at the portrait and was beside himself with joy, because he found the face very beautiful indeed.

"Is this the face of your great Queen?" he cried. They shook their heads. "Then tell me where I may find this enchanting creature!"

"This is our message: If the face is beautiful to thee and thou would'st make it thine, thou must be valiant. It is the face of our Queen's daughter, who has been carried away by a fierce demon, and none have dared seek for her."

"For that beautiful maiden?" Tamino cried in amazement. "I dare seek for her! Only tell me which way to go, and I will rescue her from all the demons of the inferno. I shall find her and make her my bride." He spoke with so much energy and passion that the ladies were quite satisfied that they had found a knight to be trusted.

"Dear youth, she is hidden in our own mountains, but – " At that moment a peal of thunder startled everybody.

"Heaven! What may that be?" Tamino cried, and even as he spoke, the rocks parted and the Queen of the Night stood before them.

"Be not afraid, noble youth. A clear conscience need have no fear. Thou shalt find my daughter, and when she is restored to my arms, she shall be thine." With this promise the Queen of the Night disappeared as suddenly as she had come. Then the poor boastful fowler began to say "hm, hm, hm, hm," and motion to his locked mouth.

"I cannot help thee, poor wretch," Tamino declared. "Thou knowest that lock was put upon thee to teach thee discretion." But one of the women went to him and told him that by the Queen's commands she now would set him free.

"And this, dear youth," she said, going to Tamino and giving him a golden flute, "is for thee. Take it, and its magic will guard thee from all harm. Wherever thou shalt wander in search of the Queen's daughter, this enchanted flute will protect thee. Only play upon it. It will calm anger and soothe the sorrowing."

"Thou, Papageno," said another, "art to go with the Prince, by the Queen's command, to Sarastro's castle, and serve him faithfully." At that the fowler was frightened half to death.

No indeed! that I decline.From yourselves have I not heardThat he's fiercer than the pard?If by him I were accostedHe would have me plucked and roasted."Have no fear, but do as you are bid. The Prince and his flute shall keep thee safe from Sarastro."

I wish the Prince at all the devils;For death nowise I search;What if, to crown my many evils,He should leave me in the lurch?He did not feel half as brave as he had seemed when he told Tamino how he had killed the serpent.

Then another of the ladies of the court gave to Papageno a chime of bells, hidden in a casket.

"Are these for me?" he asked.

"Aye, and none but thou canst play upon them. With a golden chime and a golden flute, thou art both safe. The music of these things shall charm the wicked heart and soothe the savage breast. So, fare ye well, both." And away went the two strange adventurers, Papageno and Tamino, one a prince, the other a bird-catcher.

Scene IIAfter travelling for a week and a day, the two adventurers came to a fine palace. Tamino sent the fowler with his chime of bells up to the great place to spy out what he could, and he was to return and bring the Prince news.

Without knowing it they had already arrived at the palace of Sarastro, and at that very moment Pamina, the Queen's daughter, was in great peril.

In a beautiful room, furnished with divans, and everything in Egyptian style, sat Monostatos, a Moor, who was in the secrets of Sarastro, who had stolen the Princess. Monostatos had just had the Princess brought before him and had listened malignantly to her pleadings to be set free.

"I do not fear death," she was saying; "but it is certain that if I do not return home, my mother will die of grief."

"Well, I have had enough of thy meanings, and I shall teach thee to be more pleasing; so minions," calling to the guards and servants of the castle, "chain this tearful young woman's hands, and see if it will not teach her to make herself more agreeable." As the slaves entered, to place the fetters upon her hands, the Princess fell senseless upon a divan.

"Away, away, all of you!" Monostatos cried, just as Papageno peeped in at the palace window.

"What sort of place is this?" Papageno said to himself, peering in curiously. "I think I will enter and see more of it." Stepping in, he saw the Princess senseless upon the divan, and the wretched Moor bending over her. At that moment the Moor turned round and saw Papageno. They looked at each other, and each was frightened half to death.

"Oh, Lord!" each cried at the same moment. "This must be the fiend himself."

"Oh, have mercy!" each shrieked at each other.

"Oh, spare my life," they yelled in unison, and then, at the same moment each fled from the other, by a different way. At the same instant, Pamina awoke from her swoon, and began to call pitiably for her mother. Papageno heard her and ventured back.

"She's a handsome damsel, and I'll take a chance, in order to rescue her," he determined, feeling half safe because of his chime of bells.

"Why, she is the very image of the Prince's miniature and so it must be the daughter of the Queen of the Night," he decided, taking another good look at her.

"Who art thou?" she asked him, plaintively.

"Papageno," he answered.

"I do not know the name. But I am the daughter of the Queen of the Night."

"Well, I think you are, but to make sure" – He pulled from his pocket the portrait which had been given to him by the Prince and looked at it earnestly for a long time.

"According to this you shouldn't have any hands or feet," he announced gravely.

"But it is I," the Princess declared, looking in turn at the miniature. "Pray, where did you get this?"

"Your mother gave this to a young stranger, who instantly fell in love with you, and started to find you."

"In love with me?" she cried, joyfully.

"You'd think so if you saw the way he carries on about you," the fowler volunteered. "And we are to carry you back to your mother even quicker than we came."

"Then you must be very quick about it, because Sarastro returns from the chase at noon exactly, and if he finds you here, you will never leave alive."

"Good! That will suit the Prince exactly."

"But – if I should find that, after all, you are an evil spirit," she hesitated.

"On the contrary, you will find in me the best spirits in the world, so come along."

"You seem to have a good heart."

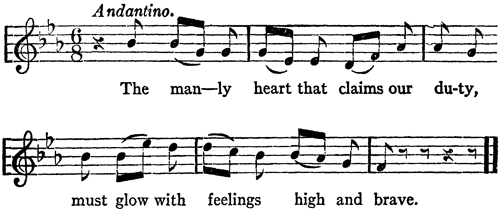

"So good that I ought to have a Papagena to share it," he answered, plaintively, whereupon Pamina sang affectingly:

[Listen]

The manly heart that claims our duty, must glow with feelings high and brave.

It is a very queer and incoherent opera, and not much sense to any of it, but, oh! it is beautiful music, and this duet between the fowler and Pamina is not the least of its beauties. At the end of it they rushed off together – Pamina to meet the Prince and be conducted back to her mother.

Scene IIIIn the meantime, Tamino, instead of looking for Pamina himself, had been invoking wisdom and help from a number of Genii he had come across. There were three temples, connected by colonnades, and above the portal of one of these was written, Temple of Wisdom; over another, Temple of Reason; the third, Temple of Nature. These temples were situated in a beautiful grove, which Tamino entered with three Genii who each bore a silver palm branch.

"Now, pray tell me, ye wise ones, is it to be my lot to loosen Pamina's bonds?" he asked anxiously.

"It is not for us to tell thee this, but we say to thee, 'Go, be a man,' be steadfast and true and thou wilt conquer." They departed, leaving Tamino alone. Then he saw the temples.

"Perhaps she is within one of these temples," he cried; "and with the words of those wise Genii in my ears, I'll surely rescue her if she is there." So saying, he went up to one of them and was about to enter.

"Stand back!" a mysterious voice called from within.

"What! I am repulsed? Then I will try the next one," and he went to another of the temples.

"Stand back," again a voice called.

"Here too?" he cried, not caring to venture far. "There is still another door and I shall betake me to it." So he went to the third, and, when he knocked, an aged priest met him upon the threshold.

"What seek ye here?" he asked.

"I seek Love and Truth."

"That is a good deal to seek. Thou art looking for miscreants, thou art looking for revenge? Love, Truth, and Revenge do not belong together," the old priest answered.

"But the one I would revenge myself upon is a wicked monster."

"Go thy way. There is none such here," the priest replied.

"Isn't your reigning chief Sarastro?"

"He is – and his law is supreme."

"He stole a princess."

"So he did – but he is a holy man, the chief of Truth – we cannot explain his motives to thee," the priest said, as he disappeared within and closed the door.

"Oh, if only she still lives!" Tamino cried, standing outside the temple.

"She lives, she lives!" a chorus within sang, and at that reassurance Tamino was quite wild with happiness. Then he became full of uncertainty and sadness again, for he remembered that he did not know where to find her, and he sat down to play upon his magic flute. As he played, wild animals came out to listen, and they crowded around him. While he was playing, lamenting the loss of Pamina, he was answered by Papageno from a little way off, and he leaped up joyously.

"Perhaps Papageno is coming with the Princess," he cried. He began to play lustily upon his flute again. "Maybe the sound will lead them here," he thought, and he hastened away thinking to overtake them. After he had gone, Pamina and Papageno ran in, she having heard the magic flute.

"Oh, what joy! He must be near, for I heard the flute," she cried, looking about. Suddenly her joy was dispelled by the appearance of Monostatos, who had flown after them as soon as he discovered Pamina's absence.

"Now I have caught you," he cried wickedly, but as he called to the slaves who attended him to bind Papageno, the latter thought of his chime of bells.

"Maybe they will save me," he cried, and at once he began to play. Then all the slaves began to dance, while Monostatos himself was utterly enchanted at the sweet sound. As the bells continued to chime, Monostatos and the slaves began to leave with a measured step, till the pair found themselves alone and once more quite safe. Then the chorus within began to sing "Long life to Sarastro," and at that the two trembled again.

"Sarastro! Now what is going to happen?" Papageno whispered.

While they stood trembling, Sarastro appeared, borne on a triumphal car, drawn by six lions, and followed by a great train of attendants and priests. The chorus all cried, "Long life to Sarastro! Long life to our guard and master!"

When Sarastro stepped from the car, Pamina knelt at his feet.

"Oh, your greatness!" she cried. "I have sorely offended thee in trying to escape, but the fault was not all mine. The wicked Moor, Monostatos, made the most violent love to me, and it was from him I fled."

"All is forgiven thee, but I cannot set thee free," Sarastro replied. "Thy mother is not a fitting guardian for thee, and thou art better here among these holy people. I know that thy heart is given to a youth, Tamino." As he spoke, the Moor entered, followed by Prince Tamino. For the first time the two lovers met, and they were at once enchanted with each other.

At once Monostatos's anger became very great, since he, too, loved the Princess. He summoned his slaves to part them. Kneeling in his turn at Sarastro's feet he protested that he was a good and valiant man, whom Sarastro knew well, and he complained that Pamina had tried to flee.

"Thou art about good enough to have the bastinado," Sarastro replied, and thereupon ordered the slaves to whip the false Moor, who was immediately led off to punishment. After that, Sarastro ordered the lovers to be veiled and led into the temple to go through certain rites. They were to endure a period of probation, and if they came through the ordeal of waiting for each other properly they were to be united.

ACT IIThe priests assembled in a grove of palms, where they listened to the story of Pamina and Tamino, told by Sarastro.

"The Princess was torn from the Queen of the Night, great priests, because that Queen would overthrow our temple, and here Pamina is to remain till purified; if you will accept this noble youth for her companion, after they have both been taught in the ways of wisdom, follow my example," and immediately Sarastro blew a blast upon a horn. All the priests blew their horns in concurrence.

Sarastro sang a hymn to the gods, and then he and his priests disappeared. Tamino and Papageno were next led in to the temple porch. It was entirely dark.

"Art thou still near me, Papageno?" he asked.

"Of course I am, but I don't feel very well. I think I have a fever. This is a queer sort of adventure."

"Oh, come, be a man. There is nothing to fear."

The priests asked Tamino at that moment why he had come to seek entrance in the temple.