полная версия

полная версияOperas Every Child Should Know

"If you must know, Little Buttercup, my daughter Josephine! the fairest flower that ever blossomed on ancestral timber" – which is very neat indeed – "has received an offer of marriage from Sir Joseph Porter. It is a great honour, Little Buttercup, but I am sorry to say my daughter doesn't seem to take kindly to it."

"Ah, poor Sir Joseph, I know perfectly what it means to love not wisely but too well," she remarks, sighing tenderly and looking most sentimentally at the Captain. She does this so capably that as she goes off the deck the Captain looks after her and remarks abstractedly:

"A plump and pleasing person!" At this blessed minute the daughter Josephine, who does not love in the right place, and who is beloved from all quarters at once, wanders upon the deck with a basket of flowers in her hand. Then she begins to sing very distractedly about loving the wrong man, and that "hope is dead," and several other pitiable things, which are very funny. The Captain, her father, is watching her, and presently he admonishes her to look her best, and to stop sighing all over the ship – at least till her high-born suitor, Sir Joseph Porter, shall have made his expected visit.

"You must look your best to-day, Josephine, because the Admiral is coming on board to ask your hand in marriage." At this Josephine nearly drops into the sea.

"Father, I esteem, I reverence Sir Joseph but alas I do not love him. I have the bad taste instead to love a lowly sailor on board your own ship. But I shall stifle my love. He shall never know it though I carry it to the tomb."

"That is precisely the spirit I should expect to behold in my daughter, my dear, and now take Sir Joseph's picture and study it well. I see his barge approaching. If you gaze upon the pictured noble brow of the Admiral, I think it quite likely that you will have time to fall madly in love with him before he can throw a leg over the rail, my darling. Anyway, do your best at it."

"My own, thoughtful father," Josephine murmurs while a song of Sir Joseph's sailors is heard approaching nearer and nearer. Then the crew of H.M.S. Pinafore take up the shout, and sing a rousing welcome to Sir Joseph and all his party. Almost immediately Sir Joseph and his numerous company of sisters and cousins and aunts prance upon the shining deck. They have a gorgeous time of it.

"Hurrah, hurrah, hurrah!" the Captain and his crew cry, and then Sir Joseph informs everybody of his greatness in this song:

[Listen]

I am the monarch of the sea,The ruler of the Queen's Navee,Whose praise Great Britain loudly chants;Cousin Hebe.And we are his Sisters and his Cousins and his Aunts;His Sisters and his Cousins and his Aunts!When at anchor here I ride,My bosom swells with pride,And I snap my fingers at the foeman's taunts —

The chorus assures everybody that

So do his sisters and his cousins and his aunts.In short, while we learn from Sir Joseph that he is a tremendous fellow, we also learn, from his sisters and his cousins and his aunts, that they are whatever he is. Among other things he tells precisely how he came to be so great, and gives what is presumably a recipe for similar greatness:

When I was a lad I served a termAs office boy to an attorney's firm.I cleaned the window and I swept the floor,And I polished up the handle of the big front door.I polished up the handle so carefullee,That now I am the ruler of the Queen's Navee.As office boy I made such a markThat they gave me the post of a junior clerk.I served the wits with a smile so bland,And I copied all the letters in a big round hand.I copied all the letters in a hand so free,That now I am the ruler of the Queen's Navee.In serving writs I made such a nameThat an articled clerk I soon became.I wore clean collars and a brand new suitFor the pass examination at the Institute.And that pass examination did so well for meThat now I am the ruler of the Queen's Navee.This was only a part of the recipe, but the rest of it was just as profound. After he is through exploiting himself, he bullies the Captain a little, and then his eye alights on Ralph Rackstraw.

"You are a remarkably fine fellow, my lad," he says to Ralph quite patronizingly.

"I am the very finest fellow in the navy," Ralph returns, honouring the spirit of the day by showing how entirely satisfied with himself he is.

"How does your Captain behave himself?" Sir Joseph asks.

"Very well, indeed, thank you. I am willing to commend him," Ralph returns.

"Ah – that is delightful – and so, with your permission, Captain, I will have a word with you in private on a very sentimental subject – in short, upon an affair of the heart."

"With joy, Sir Joseph – and, Boatswain, in honour of this occasion, see that extra grog is served to the crew at seven bells."

"I will condescend to do so," the Boatswain assures the Captain, whereupon the Captain, Sir Joseph, and his sisters and his cousins and his aunts leave the deck.

"You all seem to think a deal on yourselves," Dick Deadeye growls, as he watches these performances.

"We do, we do – aren't we British sailors? Doesn't the entire universe depend on us for its existence? We are fine fellows – Sir Joseph has just told us so."

"Yes – we may aspire to anything – " Ralph interpolates excitedly. He had begun to think that Josephine may not be so unattainable after all.

"The devil you can," responds Dick. "Only I wouldn't let myself get a-going if I were you. What if ye got going and couldn't stop?" the one-eyed gentleman inquires solicitously.

"Oh, stow it!" the crew shouts. "If we hadn't more self-respect 'n you've got, we'd put out both our eyes," the estimable crew declares, and then retires to compliment itself, – that is, all but Ralph. He leans upon the bulwark and looks pensive; and at intervals he sighs. While he is sighing his very loudest, Josephine enters. Sir Joseph has been making love to her, and she is telling herself and everybody who happens to be leaning against the bulwark sighing pensively, that the Admiral's attentions oppress her. This is Ralph's opportunity. He immediately tells her that he loves her, and she tells him to "refrain, audacious tar," but he does not refrain in the least. In short he decides upon the spot to blow out his brains. He pipes all hands on deck to see him do it, and they come gladly.

Now Ralph gets out his pistol, he sings a beautiful farewell, the Chorus turns away weeping – the sailors have just cleaned up and they cannot bear the sight of the deck all spoiled with a British sailor's brains so soon after scrubbing! Ralph lifts the pistol, takes aim – and Josephine rushes on.

"Oh, stay your hand – I love you," she cries, and in less than a minute everybody is dancing a hornpipe, except Deadeye. Deadeye is no socialist. He really thinks this equality business which makes it possible for a common sailor to marry the Captain's daughter is most reprehensible. But nobody notices Dick. Everybody is quite happy and satisfied now, and they plan for the wedding. Dick plans for revenge.

He goes apart to think matters over. The situation quite shocks his sense of propriety.

Meantime the crew and Ralph and Josephine decide that:

This very night,With bated breathAnd muffled oar,Without a light,As still as death,We'll steal ashore.A clergymanShall make us oneAt half-past ten,And then we canReturn, for noneCan part us then.Thus the matter is disposed of.

ACT IIIt is about half-past ten, and everything ready for the elopement. The Captain is on deck playing a mandolin while holding a most beautiful pose (because Little Buttercup is also "on deck," and looking sentimentally at him). The Captain sings to the moon, quite as if there were no one there to admire him; because while this "levelling" business is going on in the Navy there seems no good reason why Buttercup or any other thrifty bumboat lady shouldn't do a little levelling herself. Now to marry the Captain – but just now, even though it is moonlight and a very propitious moment, there is other work on hand than marrying the Captain. She can do that almost any time! But at this moment she has some very mysterious and profound things to say to him. She tells him that:

Things are seldom what they seem,Skim milk masquerades as cream.High-lows pass as patent leathers,Jackdaws strut in peacock feathers.And the Captain acquiesces.

Black-sheep dwell in every fold.All that glitters is not gold.Storks turn out to be but logs.Bulls are but inflated frogs.And again the Captain wisely acquiesces.

Drops the wind and stops the mill.Turbot is ambitious brill.Gild the farthing if you will,Yet it is a farthing still.And again the Captain admits that this may be true. It is quite, quite painful if it is. On the whole, the Captain fears she has got rather the best of him, so he determines to rally; he philosophises a little himself, when he has time. He has time now:

Tho' I'm anything but clever,he declares rhythmically, even truthfully;

I could talk like that forever,Once a cat was killed by care,Only brave deserve the fair.He has her there, beyond doubt, because all she can say is "how true."

Thus encouraged he continues:

Wink is often good as nod;Spoils the child, who spares the rod;Thirsty lambs run foxy dangers,Dogs are found in many mangers.Buttercup agrees; – she can't help it.

Paw of cat the chestnut snatches;Worn-out garments show new patches;Only count the chick that hatches,Men are grown-up catchy-catches.And Little Buttercup assents that this certainly is true. And then, just as she has worked the Captain up into a pink fit of apprehension she leaves him. While he stands looking after her and feeling unusually left alone, Sir Joseph enters and declares himself very much disappointed with Josephine.

"What, won't she do, Sir Joseph?" the Captain asks disappointedly.

"No, no. I don't think she will. I have stooped as much as an Admiral ought to, by presenting my sentiments almost – er – you might say emotionally, but without success; and now really I – "

"Well, it must be your rank which dazzles her," the Captain suggests, and thinks how he would like to take a cat-o'-nine-tails to her.

"She is coming on deck," Sir Joseph says, softly, "and we might watch her unobserved a moment. Her actions while she thinks herself alone, may reveal something to us that we should like to know"; and Sir Joseph and the Captain step behind a convenient coil of rope while Josephine walks about in agitation and sings to herself how reckless she is to leave her luxurious home with her father, for an attic that, likely as not, will not even be "finished off."

Of course Sir Joseph and her father do not understand a word of this, but they understand that she is disturbed, and Sir Joseph steps up and asks her outright, if his rank overwhelms her. He assures her that it need not, because there is no difference of rank to be observed among those of her Majesty's Navy – which he doesn't mean at all except for one occasion only, of course. At the same time, it is an admirable plea for his rival Ralph.

Now it is rapidly becoming time for the elopement, and Josephine pretends to accept Sir Joseph's suit at last, in order to get rid of him at half-past ten. He and Josephine go below while Dick Deadeye intimates to the Captain that he wants a word with him aside.

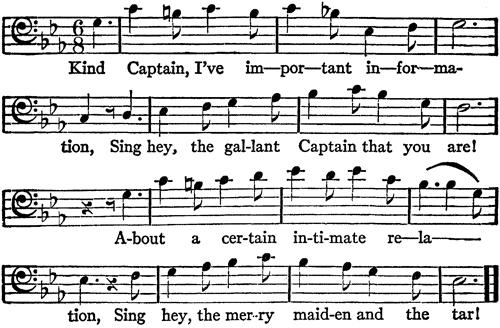

Then Dick Deadeye gives the Captain his information, thus:

[Listen]

Kind Captain, I've important information,Sing hey, the gallant Captain that you are!About a certain intimate relation,Sing hey, the merry maiden and the tar!Kind Captain, your young lady is a-sighing,Sing, hey, the gallant Captain that you are!This very night with Rackstraw to be flying,Sing, hey, the merry maiden and the tar!

This information certainly comes in the nick of time, so the Captain hastily throws an old cloak over him and squats down behind the deck furniture to await the coming of the elopers.

Presently they come up, Josephine, followed by Little Buttercup, and all the crew on "tip-toe stealing." Suddenly amid the silence, the Captain stamps.

"Goodness me!" all cry. "What was that?"

"Silent be," says Dick. "It was the cat," and thus reassured they start for the boat which is to take the lovers ashore. At this crisis the Captain throws off the cloak and creates a sensation. He is so mad he swears just as Sir Joseph puts in an appearance.

"Damme!" cries the Captain.

"What was that dreadful language I heard you use?" Sir Joseph demands, highly scandalized.

"He said 'damme,'" the crew assure him. Sir Joseph is completely overcome. To excuse himself the Captain is obliged to reveal the cause of his anger.

"My daughter was about to elope with a common sailor, your Greatness," he says, and at this moment Josephine rushes into the arms of Ralph. The Admiral is again overcome with the impropriety of the situation.

"My amazement and my surprise, you may learn from the expression of my eyes," the Admiral says. "Has this sailor dared to lift his eyes to the Captain's daughter? Incredible. Put him in chains, my boys," he says to the rest of the crew, "and Captain – have you such a thing as a dungeon on board?"

"Certainly," the Captain says. "Hanging on the nail to the right of the mess-room door – just as you go in."

"Good! put him in the ship's dungeon at once – just as you go in – and see that no telephone communicates with his cell," whereupon Ralph is lugged off.

"When the secret I have to tell is known," says Little Buttercup, "his dungeon cell will be thrown wide."

"Then speak, in Heaven's name; or I certainly shall throw myself into the bilge water," Josephine says desperately.

"Don't do that: it smells so dreadfully," Buttercup entreats; "and to prevent accidents I will tell what I know:"

A many years ago,When I was young and charming,As some of you may know,I practised baby farming.Two tender babes I nursed,One was of low condition,The other upper crust —A regular patrician.Oh, bitter is my cup,However could I do it?I mixed those children up,And not a creature knew it.In time each little waif,Forsook his foster-mother;The well-born babe was Ralph —Your Captain was the other!So, the murder is out! Nobody outside of comic opera can quite see how this fact changes the status of the Captain and Ralph (the Captain not having been a captain when in the cradle) but it is quite enough to set everybody by the ears. Josephine screams:

"Oh, bliss, oh, rapture!" And the Admiral promptly says:

"Take her, sir, and mind you treat her kindly," and immediately, having fixed the ship's affairs so creditably, falls to bemoaning his sad and lonesome lot.

He declares that he "cannot live alone," and his cousin Hebe assures him she will never give up the ship; or rather that she never will desert him, unless of course she should discover that he, too, was changed in the cradle. This comforts everybody but the changed Captain. Ralph has, in the twinkling of an eye, become the Captain of the good ship Pinafore, while the Captain has become Ralph, and Ralph has taken the Captain's daughter. But while he is looking very downcast, Buttercup reminds him that she is there, and after regarding her tenderly for a moment, he decides that he has always loved his foster mother like a wife, and he says so:

I shall marry with a wife,In my humble rank of life,And you, my own, are she.The crew is delighted. Everybody is happy. But the Captain adds, rashly:

I must wander to and fro,But wherever I may goI shall never be untrue to thee!Whereupon the crew, which is very punctilious where the truth is concerned, cries:

"What, never?"

"No, never!" the Captain declares.

"What – never?" they persist.

"Well, hardly ever," the Captain says, qualifying the statement satisfactorily to his former crew. And now that all the facts and amenities of life have been duly recognized, the crew and Sir Joseph, Ralph and the former Captain, Josephine and Buttercup, all unite in singing frantically that they are an Englishman, for they themselves have said it, and it's greatly to their credit; and while you are laughing yourself to death at a great many ridiculous things which have taken place, the curtain comes down with a rush, and you wish they would do it again.

VERDI

GIUSEPPE VERDI, born October 9, 1813, was the composer of twenty-six operas. His musical history may be divided into three periods, and in the last he approached Wagner in greatness, and frequently surpassed him in beauty of idea.

Wagner made both the libretti and the music of his operas, while Verdi took his opera stories from other authors. Both of these great men were born in the same year.

Of Verdi's early operas, "Ernani" was probably the best; then he entered upon the second period of his achievement as a composer, and the first work that marked the transition was "Rigoletto." The story was adapted from a drama of Hugo's, "Le Roi S'Amuse," and as the profligate character of its principal seemed too baldly to exploit the behaviour of Francis I, its production was suppressed. Then Verdi adjusted the matter by turning the character into the Duke of Mantua, and everybody was happy.

The story of the famous song "La Donna è Mobile," is as picturesque as Verdi himself. While the rehearsals of the opera were going on, Mirate, who sang the Duke, continued to complain that he hadn't the MS. of one of his songs. Verdi kept putting him off, till the evening before the orchestral rehearsal, when he brought forth the lines; but at the same time he demanded a promise that Mirate – nor indeed any of the singers – should not hum or whistle the air till it should be heard at the first performance. This signified Verdi's belief that the song would instantly become a universal favourite. The faith was justified. The whole country went "La Donna" mad.

"Il Trovatore" came next in this second period of the great composer's fame, and we read that "Nearly half a century has sped since Verdi's twelfth opera was first sung of a certain winter evening in Rome." Out of the chaff of Italian opera comes this wheat, satisfying to the generation of to-day, as it was to that first audience in Rome. We do not even know any longer why we love it, because in most ways it violates new and better rules of musical art, but we love it. Helen Keyes has written that "the libretto of 'Il Trovatore' is based on a Spanish drama written in superb verse by a contemporary of Verdi's, Antonio Garcia Gutierrez," and she relates a romantic story in connection with the Spanish play; the author was but seventeen years old when he wrote it and had been called to military duty, which was dreaded by one of his temperament. But his drama being staged at that moment, the authorities permitted him to furnish a substitute on the ground that such genius could best serve its country by remaining at home to contribute to its country's art.

At the time the opera was produced in Rome, the Tiber had overflowed its banks and had flooded all the streets near the theatre; nevertheless people were content to stand knee-deep in water at the box office, waiting their turn for tickets.

So great had Verdi become in a night, by this presentation, that his rivals formed a cabal which prevented the production of "Il Trovatore" in Naples for a time, but in the end the opera and Verdi prevailed.

Now came "Traviata," – third in that time of change in a great master's art, and this marked the limits of the second period. "Aïda" followed. It is well said that "the importance of Verdi's 'Aïda' as a work of musical art can hardly be overestimated!" This opera was written at the entreaty of the Khedive Ismail Pacha. He wished to open the opera house at Cairo with a great opera that had Egypt for its dramatic theme. Upon the Khedive's application Verdi named a price which he believed would not be accepted, as he felt no enthusiasm about the work. But his terms were promptly approved and Mariette Bey, a great Egyptologist, was commissioned to find the materials for a proper story. Verdi, in the meantime, did become enthusiastic over the project and went to work. Egyptian history held some incident upon which the story of "Aïda" was finally built. First, it was given to Camille du Locle, who put the story into French prose, and in this he was constantly advised by Verdi, at whose home the work was done. After that, the French prose was translated into Italian verse by Ghislanzoni, and when all was completed, the Italian verse was once more translated back into French for the French stage.

Then the Khedive decided he would like Verdi to conduct the first performance, and he began to negotiate for that. Verdi asked twenty thousand dollars for writing the opera, and thirty thousand in case he went to Egypt. This was agreed, but when the time came to go, Verdi backed out; he was overcome with fear of seasickness and wouldn't go at any price. Then the scenery was painted in Paris, and when all was ready – lo! the scenery was a prisoner because the war had broken out in France! Everything had to wait a year, and during that time Verdi wrote and rewrote, making his opera one of the most beautiful in the world. Finally "Aïda" was produced, and the story of that night as told by the Italian critic Filippi is not out of place here, since the night is historic in opera "first nights:"

"The Arabians, even the rich, do not love our shows; they prefer the mewings of their tunes, the monotonous beatings of their drums, to all the melodies of the past, present, and future. It is a true miracle to see a turban in a theatre of Cairo. Sunday evening the opera house was crowded before the curtain rose. Many of the boxes were filled with women, who neither chatted nor rustled their robes. There was beauty and there was intelligence especially among the Greeks and the strangers of rank who abound in Cairo. For truth's sake I must add that, by the side of the most beautiful and richly dressed, were Coptic and Jewish faces, with strange head-dresses, impossible costumes, a howling of colours, – no one could deliberately have invented worse. The women of the harem could not be seen. They were in the first three boxes on the right, in the second gallery. Thick white muslin hid their faces from prying glances."

This gives a striking picture of that extraordinary "first night."

Verdi was born at a time of turmoil and political troubles, and his mother was one of the many women of the inhabitants of Roncole (where he was born) who took refuge in the church when soldiery invaded the village. There, near the Virgin, many of the women had thought themselves safe, but the men burst in, and a general massacre took place. Verdi's mother fled with her little son to the belfry and this alone saved to the world a wonderful genius.

When Verdi was ten years old he was apprenticed to a grocer in Busseto, but he was a musical grocer, and the musical atmosphere, which was life to Verdi, surrounded him. He had a passion for leaving in the midst of his grocery business to sit at the spinet and hunt out new harmonious combinations: and when one of his new-made chords was lost he would fly into a terrible rage, although as a general rule he was a peaceable and kindly little chap. On one such occasion he became so enraged that he took a hammer to the instrument – an event coincident with a thrashing his father gave him.

There is no end of incident connected with this gentle and kindly soul, who, unlike so many of his fellow geniuses, reflected in his life the beauty of his art.

RIGOLETTO

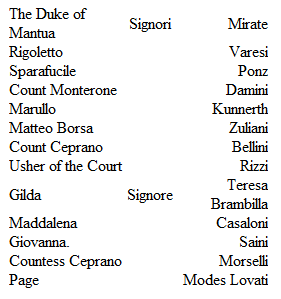

CHARACTERS OF THE OPERA, WITH THE ORIGINAL CAST AS PRESENTED AT THE FIRST PERFORMANCE

The story belongs to the sixteenth century, in the city of Mantua and its environs.

Composer: Giuseppe Verdi. Author: Francesco Maria Piave.

First sung in Venice, Gran Teatro la Fenice. March 11, 1851.

ACT IDukes and duchesses, pages and courtiers, dancing and laughter: these things all happening to music and glowing lights, in the city of Mantua four hundred years ago! – that is "Rigoletto."