полная версия

полная версияOperas Every Child Should Know

"Yes, Turiddu – I warn you!" At that Lola laughed and went into the church.

"Now what have you done? By your folly, angered Lola. I am done with you!" Turiddu exclaimed, throwing off Santuzza, who held him back while she spoke. He became so enraged that he treated her brutally; and in trying to rid himself of her he threw her down upon the stones, and then ran into the church. When she got upon her feet again she was furious with anger.

"Now I will punish him for all his faithlessness," she sobbed, and she no sooner took this resolve than fate seemed to give her the means of carrying it out, for at that moment Alfio came back into the square.

"Oh, neighbour Alfio! God himself must have sent you here!"

"At what point is the service?"

"It is almost over, but I must tell you – Lola is gone to it with Turiddu."

"What do you mean by that?" Alfio demanded, regarding her in wonder.

"I mean that while you are about your business Turiddu remains here, and your wife finds in him a way to pass the time. She does not love you."

"If you are not telling me the truth," Alfio said, with anguish, "I'll certainly kill you."

"You have only to watch – you will know the truth fast enough," she persisted.

Alfio stood a moment in indecision and looked at her steadfastly.

"Santuzza, I believe you. Your words – and the sadness of your face – convince me. I will avenge us both." And off he ran. For a moment Santuzza was glad, then remorse overtook her. Now Turiddu would be killed! She was certain of it. Alfio was not a man to be played with. Surely Turiddu would be killed! And there was his old mother, too, who would be left quite alone. When it was too late, Santuzza repented having spoken. She tried to recall Alfio, but he had gone.

The organ within the church swelled loudly again, and, the music being most beautiful, Santuzza stood listening in an agony of mind. Soon people began to come out, and old Lucia hobbled from the church in her turn, and crossed to her inn, followed by the young men and women. The men were all going home to their wives, and the women to their duties, but it was proposed that all should stop a moment at old Lucia's for a glass of her famous wine before they separated. As they went to the bar of the inn, which was out under the trees, Lola and Turiddu came from the church together.

"I must hurry home now – I haven't seen Alfio yet – and he will be in a rage," she said.

"Not so fast – there is plenty of time! Come, neighbours, have a glass of wine with us," Turiddu cried to the crowd, going to his mother's bar, and there they gathered singing a gay drinking song.

"To those who love you!" Turiddu pledged, lifting his glass and looking at Lola. She nodded and answered:

"To your good fortune, brother!" And while they were speaking Alfio entered.

"Greeting to you all," he called.

"Good! come and join us," Turiddu answered.

"Thank you! but I should expect you to poison me if I were to drink with you, my friend," and the wagoner looked meaningly at Turiddu.

"Oh – well, suit yourself," Turiddu replied, nonchalantly. Then a neighbour standing near Lola whispered:

"You had better leave here, Lola. Come home with me. I can foresee trouble here." Lola took her advice and went out, with all the women following her.

"Well, now that you have frightened away all the women by your behaviour, maybe you have something to say to me privately," Turiddu remarked, turning to Alfio.

"Nothing – except that I am going to kill you – this instant!"

"You think so? then we will embrace," Turiddu exclaimed, proposing the custom of the place and throwing his arms about his enemy. When he did so, Alfio bit Turiddu's ear, which, in Sicily, is a challenge to a duel.

"Good! I guess we understand each other."

"Well, I own that I have done you wrong – and Santuzza wrong. Altogether, I am a bad fellow; but if you are going to kill me, I must bid my mother good-bye, and also give Santuzza into her care. After all, I have some grace left, whether you think so or not," Turiddu cried, and then he called his mother out, while Alfio went away with the understanding that Turiddu should immediately follow and get the fight over.

"Mama," Turiddu then said to old Lucia when she hobbled out, "that wine of ours is certainly very exciting. I am going out to walk it off, and I want your blessing before I go." He tried to keep up a cheerful front that he might not frighten his old mother. At least he had the grace to behave himself fairly well, now that the end had come.

"If I shouldn't come back – "

"What can you mean, my son?" the old woman whispered, trembling with fear.

"Nothing, nothing, except that even before I go to walk, I want your promise to take Santuzza to live with you. Now that is all! I'm off. Good-bye, God bless you, mother. I love you very much." Before she hardly knew what had happened, Turiddu was off and away. She ran to the side of the square and called after him, but he did not return. Instead, Santuzza ran in.

"Oh, Mama Lucia," she cried, throwing her arms about her.

Then the people who had met Alfio and Turiddu on their way to their encounter began to rush in. Everybody was wildly excited. Both men were village favourites in their way. A great noise of rioting was heard and some one shrieked in the distance.

"Oh, neighbour, neighbour, Turiddu is killed, Turiddu is killed!" At this nearly every one in the little village came running, while Santuzza fell upon the ground in a faint.

"He is killed! Alfio has killed him!" others cried, running in, and then poor old Lucia fell unconscious beside Santuzza, while the neighbours gathered about her, lifted her up and carried her into her lonely inn.

MEYERBEER

GENIUS seems born to do stupid things and to be unable to know it. Probably no stupider thing was ever said or done than that by Wagner when he wrote a diatribe on the Jew in Art. He called it "Das Judenthum in der Musik" (Judaism in Music). He declared that the mightiest people in art and in several other things – the Jews – could not be artists for the reason that they were wanderers and therefore lacking in national characteristics.

There could not well have been a better plea against his own statement. Art is often national – but not when art is at its best. Art is an emotional result – and emotion is a thing the Jews know something about. Meyerbeer was a Jew, and the most helpful friend Richard Wagner ever had, yet Wagner was so little of a Jew that he did not know the meaning of appreciation and gratitude. Instead, he hated Meyerbeer and his music intensely. Meyerbeer may have been a wanderer upon the face of the earth and without national characteristics – which is a truly amusing thing to say of a Jew, since his "characteristics" are a good deal stronger than "national": they are racial! But however that may have been, Meyerbeer's music was certainly characteristic of its composer. As between Jew and Jew, Mendelssohn and he had a petty hatred of each other. Mendelssohn was always displeased when the extraordinary likeness between himself and Meyerbeer was commented upon. They were so much alike in physique that one night, after Mendelssohn had been tormented by his attention being repeatedly called to the fact, he cut his hair short in order to make as great a difference as possible between his appearance and that of his rival. This only served to create more amusement among his friends.

Rossini, with all the mean vanity of a small artist, one whose principal claim to fame lay in large dreams, declared that Meyerbeer was a "mere compiler." If that be true, one must say that a good compilation is better than a poor creation. Rossini and Meyerbeer were, nevertheless, warm friends.

Meyerbeer put into practice the Wagnerian theories, which may have been one reason, aside from the constitutional artistic reasons, why Wagner hated him.

Meyerbeer was born "to the purple," to a properly conducted life, and yet he laboured with tremendous vim. He outworked all his fellows, and one day when a friend protested, begging him to take rest, Meyerbeer answered:

"If I should stop work I should rob myself of my greatest enjoyment. I am so accustomed to it that it has become a necessity with me." This is the true art spirit, which many who "arrive" never know the joy of possessing. Meyerbeer's father was a rich Jewish banker, Jacob Beer, of Berlin. It is pleasant to think of one man, capable of large achievements, having an easy time of it, finding himself free all his life to follow his best creative instincts. It is not often so.

Meyerbeer's generosity of spirit in regard to the greatness of another is shown in this anecdote:

Above all music, the Jew best loved Mozart's, just as Mozart loved Haydn's. Upon one occasion when Meyerbeer was dining with some friends, a question arose about Mozart's place among composers. Some one remarked that "certain beauties of Mozart's music had become stale with age." Another agreed, and added, "I defy any one to listen to 'Don Giovanni' after the fourth act of 'Les Huguenots'!" This vulgar compliment enraged Meyerbeer. "So much the worse then for the fourth act of 'The Huguenots'!" he shouted. Of all his own work this Jewish composer loved "L'Africaine" the best, and he made and remade it during a period of seventeen years. In this he was the best judge of his own work; though some persons believe that "Le Prophète" is greater.

Among Meyerbeer's eccentricities was one that cannot be labelled erratic. He had a wholesome horror of being buried alive, and he carried a slip about in his pocket, instructing whom it might concern to see that his body was kept unburied four days after his death, that small bells were attached to his hands and feet, and that all the while he should be watched. Then he was to be sent to Berlin to be interred beside his mother, whom he dearly loved.

THE PROPHET

CHARACTERS OF THE OPERACount Oberthal, Lord of the manor.

John of Leyden, an innkeeper and then a revolutionist (the Prophet).

Bertha, affianced to John of Leyden.

Faith, John's mother.

Choir: Peasants, soldiers, people, officersStory laid in Holland, near Dordrecht, about the fifteenth century.

Composer: Meyerbeer.

Author: Scribe.

ACT IOne beautiful day about four hundred years ago the sun rose upon a castle on the Meuse, where lived the Count Oberthal, known in Holland as Lord of the Manor. It was a fine sight with its drawbridge and its towers, its mills and outbuildings, with antique tables outside the great entrance, sacks of grain piled high, telling of industry and plenty. In the early day peasants arrived with their grain sacks, called for entrance, and the doors were opened to them; other men with grain to be milled came and went, and the scene presented a lively appearance.

Sheep-bells were heard in the meadows, the breezes blew softly, and men and women went singing gaily about their work. Among them was a young girl, more beautiful than the others, and her heart was specially full of hope. She was beloved of an innkeeper, John, who lived in a neighbouring village. He was prosperous and good, and she thought of him while she worked. She longed to be his wife, but John had an old mother who was mistress of the inn – in fact, the inn was hers – and it had been a question how they should arrange their affairs. John was too poor to go away and make a separate home, and the old mother might not care to have a daughter-in-law take her place as mistress there, carrying on the business while the active old woman sat idly by.

Upon that beautiful day, Bertha was thinking of all of these things, and hoping something would happen to change the situation. Even while she was thinking thus fate had a pleasant surprise in store for her, because the old mother, Faith, was at that very moment approaching the manor where Bertha lived. Like others of her class she owed vassalage to some petty seigneur, and while that meant oppression to be endured, it included the advantage of safety and protection in time of war.

Bertha, looking off over the country road, saw Faith, John's mother, coming. Her step was firm for one so aged, and she was upheld on her long journey by the goodness of her mission. When Bertha saw her she ran to meet and welcome her.

"Sit down," she cried, guiding the old woman's steps to a seat, and hovering over her. "I have watched for your coming since the morning – even since sunrise," the young woman said, fluttering about happily. "I was certain thou wert coming."

"Yes, yes. John said: 'Go, go, mother, and bring Bertha home to me,' and I have come," she answered, caressing Bertha kindly. "I have decided to give over the work and the care to you young people; to sit by the chimneyside and see you happy; so bid farewell to this place, and prepare to return with me. John is expecting thee."

"At once, dear mother?" she asked with some anxiety. "You know, mother, I am a vassal of the Seigneur Oberthal, and may not marry outside of his domain, without his permission. I must first get that; but he cannot wish to keep me here, when there is so much happiness in store for me!" she cried, with all the assurance of her happiness newly upon her. But while she had been speaking, Faith had looked off toward the high-road:

"Look, Bertha! dost see three strange figures coming along there?" she asked in a low tone, pointing toward the road. Bertha looked. It was true: three men, in black, of sinister appearance, were coming toward them. The pair watched.

"Who are they?" she repeated, still in low and half-frightened tones.

"I have seen them before," Bertha answered. "It is said that they are saintly men, but they look sinister to me."

By this time the men had been joined by many of the peasants and were approaching the castle. They were Jonas, Mathison, and Zacharia, seditionists; but they were going through the country in the garb of holy men, stirring up the people under cover of saintliness.

They preached to the people the most absurd doctrines; that they would have all the lands and castles of the nobles if they should rise up and rebel against the system of vassalage that then prevailed. They lacked a leader, however, in order to make their work successful. Now they had come to Dordrecht and were approaching the castle of the Count of Oberthal. All the peasants got into a frightful tangle of trouble and riot, and they called and hammered at the Count's doors till he and his retainers came out.

"What is all this noise?" he demanded, and as he spoke, he recognized in Jonas, the leader of the Anabaptists, a servant whom he had discharged for thievery. He at once told the peasants of this, and it turned them against the three strangers and stopped the disturbance, but at the back of the crowd the Count Oberthal had seen the beautiful Bertha and Faith.

"What do ye do here?" he asked, curiously but kindly, noticing the beauty of Bertha. At that she went toward him.

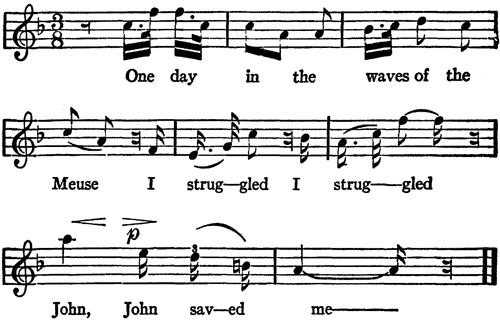

"I wish to ask you, Seigneur, for leave to marry outside your domain. I love John of Leyden, the innkeeper – this is his mother – and she has come to take me home with her, if I may go." She spoke modestly, never thinking but she would be permitted to leave. But Oberthal looked at her admiringly and decided that he would have her for himself. Then thinking of her love, she began to sing of how John had once saved her life, and Faith joined her in pleading.

[Listen]

One day in the waves of the MeuseI struggled I struggledJohn, John saved me —

"No," Oberthal said at last, smiling; "I will not have so much loveliness leave my domain. No! I shall not give my consent." At that she began to weep, while Faith protested against his decision. This made him angry and he ordered the two woman taken into his castle and confined there till he should decide what he wished to do with them.

The peasants, who were still gathered about the Anabaptists, uncertain how to treat them after the Count's disclosures, now showed great anger against Oberthal for his action toward Bertha and Faith. As the two women were dragged within the castle, the peasants set up a howl of rage, while the Anabaptists extended their hands above them in a pious manner and began their Latin chant once more.

ACT IIAt the little inn belonging to Faith, John had been waiting all day for her return with Bertha, and trying his best to look after those who came and went. Outside, people were waltzing and drinking and making merry, for the inn was a favourite place for the townsmen of Leyden to congregate.

"Sing and waltz; sing and waltz!" they cried, "all life is joy – and three cheers for thee, John!"

"Hey! John, bring beer," a soldier called merrily. "Let us eat, drink and – " At that moment Jonas, followed by the other Anabaptists, appeared at the inn.

"John! who is John?" they inquired of the soldier.

"John! John!" first one, then another called. "Here are some gentlemen who want beer – although they are very unlikely looking chaps," some one added, under his breath, looking the three fellows over. John came in to take orders, but his mind was elsewhere.

"It is near night – and they have not come," he kept thinking. "I wonder if anything can have happened to them! Surely not! My mother is old, but she is lively on her feet, and on her way home she would have the attention of Bertha. Only I should feel better to see them just now."

"Come, come, John! Beer!" the soldier interrupted, and John started from his reverie. As he went to fetch the beer, Jonas too started. Then he leaned toward Mathison.

"Do you notice anything extraordinary about that man – John of the inn?" he asked. The two other Anabaptists regarded the innkeeper closely.

"Yes! He is the image of David – the saint in Münster, whose image is so worshipped by the Westphalians. They believe that same saint has worked great miracles among them," Zacharia answered, all the while watching John as he moved about among the tables.

"Listen to this! Just such a man was needed to complete our success. This man's strong, handsome appearance and his strange likeness to that blessed image of those absurd Westphalians is enough to make him a successful leader. We'll get hold of him, call him a prophet, and the business is done. With him to lead and we to control him, we are likely to own all Holland presently. He is a wonder!" And they put their heads together and continued to talk among themselves. Then Jonas turned to one of the guests.

"Say, friend, who is this man?"

"He is the keeper of this inn," was the answer. "He has an excellent heart and a terrible arm."

"A fiery temper, I should say," the Anabaptist suggested.

"That he has, truly."

"He is brave?"

"Aye! and devoted. And he knows the whole Bible by heart," the peasant declared, proud of his friend. At that the three looked meaningly at one another. This certainly was the sort of man they needed.

"Come, friends, I want you to be going," John said at that moment, his anxiety for his mother and Bertha becoming so great that he could no longer bear the presence of the roistering crowd. "Besides it is going to storm. Come. I must close up." They all rose good-naturedly and one by one and in groups took themselves off – all but the three Anabaptists, who lingered behind.

"What troubles thee, friend?" Jonas said sympathetically to John, when all had gone, and he looked toward them inquiringly.

"The fact is, my mother was to have returned to Leyden with my fiancée before this hour, and I am a little troubled to know they are so late upon the road. I imagine I feel the more anxious because of some bad dreams I have had lately – two nights." He added, trying to smile.

"Pray tell us what your dreams were. We can some of us interpret dreams. Come! Perhaps they mean good rather than bad," Jonas urged.

"Why, I dreamed that I was standing in a beautiful temple, with everything very splendid about me, while everybody was bowing down to me – "

"Well, that is good!" Jonas interrupted.

"Ah! but wait! A crown was on my brow and a hidden choir were chanting a sacred chant. They kept repeating: 'This is the new king! the king whom heaven has given us.' And then upon a blazing marble tablet there appeared the words 'Woe through thee! Woe through thee!' And as I was about to draw my sword I was nearly drowned in a sea of blood. To escape that I tried to mount the throne beside me. But I and the throne were swept away by a frightful storm which rose. And at that moment the Devil began to drag me down, while the people cried: 'Let him be accursed!' But out of the sky came a voice and it cried 'Mercy – mercy to him!' and then I woke trembling with the vividness of my dream. I have dreamed thus twice. It troubles me." And he paused abstractedly, listening to the storm without, which seemed to grow more boisterous.

"Friend, let me interpret that dream as it should be understood. It means that you are born to reign over the people. You may go through difficulties to reach your throne, but you shall reign over the people."

"Humph!" he answered, smiling incredulously, "I may reign, but it shall be a reign of love over this little domestic world of mine. I want my mother and my sweetheart, and want no more. Let them arrive safely this night, and I'll hand over that dream-throne to you!" he answered, going to the door.

"Listen again!" Jonas persisted. "You do not know us but you have heard of us. We are those holy men who have been travelling through Holland, telling people their sacred rights as human beings; and pointing out to them that God never meant them for slaves. Join us, and that throne you dreamed of shall become a real one, and thine! Come! Consent, and you go with us. That kingdom shall be yours. You have the head and heart and the behaviour of a brave and good man." Thus they urged him, but John only put them aside. He listened to them half in derision.

"Wait till I get my Bertha and my mother safe into this house this night, then we'll think of that fine kingdom ye are planning for me," he said. The Anabaptists seeing that his mind was too troubled with his own affairs, got up and went out.

"Well, thank heaven!" John cried when they had gone. "What queer fellows, to be sure! I wish it were not so late – " At that moment a great noise arose outside the inn. "What can that mean?" he said to himself, standing in the middle of the floor, hardly daring to look out, he was so disturbed. The noise became greater.

"It is the galloping of soldiers, by my faith!" he cried, and was starting toward the door when it was burst open and Bertha threw herself into his arms.

"What is this! What has happened? Good heaven! you are all torn and – "

"Save me, save and hide me!" she cried. "Thy mother is coming. The soldiers are after us – look!" And glancing toward the window he saw Oberthal coming near with his soldiers. He hastily hid Bertha behind some curtains in one part of the room, just as Oberthal rushed in.

He demanded Bertha, telling John how he had taken the two women and was carrying them to Haarlem when Bertha got away. Now he had Faith, the mother, and would keep her as hostage, unless Bertha was instantly given into his hands. Upon hearing that, John was distracted with grief.

"Give her up, or I'll kill this old woman before thy eyes!" he declared brutally. John was torn between love for his old mother and for his sweetheart, and while he stood staring wildly at Oberthal the soldiers brought his mother in and were about to cleave her head in twain when Bertha tore the curtains apart. She could not let John sacrifice his mother for her. Oberthal fairly threw her into the arms of his soldiers, while the old mother stretched her arms toward John, who fell upon a seat with his head in his hands. Then, after the soldiers and Oberthal had gone, the poor old woman tried to comfort him, but his grief was so tragic that he could not endure it, and he begged her to go to her room and leave him alone for a time. Soon after she had gone out, John heard the strange chant of the Anabaptists. He raised his head and listened – that was like his dream – the sacred chant!