полная версия

полная версияOperas Every Child Should Know

"I came to find Friendship and Love," he replied.

"If you would have that, you must go through every trial; and how about you, Papageno?"

"Well, I do not care as much as I might for wisdom. Give me a nice little wife and a good bird-market, and I shall get on.'"

"But thou canst not have those things, unless thou canst undergo our trials."

"Oh, well, I'll stay and face it out – but I must be certain of a wife at the end of it. Her name must be Papagena – and I'd like to have a look at her before I undertake all this sort of thing," he persisted.

"Oh, that is quite reasonable – but thou must promise not to speak with her."

"And Pamina?" Tamino suggested.

"Certainly – only thou too must not speak." Thus it was agreed, and the priests went out. Instantly the place was in darkness again.

"I should like to know why, the moment those chaps go out, we find ourselves in the dark?" Papageno demanded.

"That is one of our tests; one of our trials," Tamino responded. "Take it in good part." He was interrupted by the appearance of the three ladies of the Queen of the Night's court.

"Why are you in this place?" they demanded seductively. "It will ruin you."

"Do not say so," Tamino returned, stoutly, this being one of the temptations he was to meet: but Papageno was frightened enough. "Stop thy babbling, Papageno," Tamino cautioned. "Or thou wilt lose thy Papagena."

In short, the ladies did all that was possible to dishearten the youth and Papageno; but the Prince Tamino stood firm, and would not be frightened nor driven from his vow to the temple; but Papageno found himself in an awful state of mind, and finally fell down almost in a fit. At once the ladies sank through the temple floor.

Then the priests and a spokesman appeared and praised Tamino, threw another veil over him and led him out; but when a priest inquired of Papageno how it was with him, that fine gentlemen was so addled that he couldn't tell.

"For me – I'm in a trance," he exclaimed.

"Well, come on," they said, and threw a veil over him also.

"This incessant marching takes away all thought of love," he complained.

"No matter, it will return"; and at that the priests marched him out, and the scene changed to a garden where Pamina was sleeping.

Scene IIMonostatos was watching the beautiful Pamina sleep, and remarking that, if he dared, he certainly should kiss her. In short, he was a person not to be trusted for a moment. He stole toward her, but in the same instant the thunder rolled and the Queen of the Night appeared from the depths of the earth.

"Away," she cried, and Pamina awoke.

"Mother, mother," she screamed with joy, while Monostatos stole away. "Let us fly, dear mother," Pamina urged.

"Alas, with thy father's death, I lost all my magic power, my child. He gave his sevenfold Shield of the Sun to Sarastro, and I have been perfectly helpless since."

"Then I have certainly lost Tamino," Pamina sobbed somewhat illogically.

"No, take this dagger and slay Sarastro, my love, and take the shield. That will straighten matters out."

Then the bloody Queen sang that the fires of hell were raging in her bosom. Indeed, she declared that if Pamina should not do as she was bidden and slay the priest, she would disown her. Thus Pamina had met with her temptation, and while she was rent between duty and a sense of decency – because she felt it would be very unpleasant to kill Sarastro – Monostatos entered and begged her to confide in him, that he of all people in the world was best able to advise her.

"What shall I do, then?" the trusting creature demanded.

"There is but one way in the world to save thyself and thy mother, and that is immediately to love me," he counselled.

"Good heaven! The remedy is worse than the disease," she cried.

"Decide in a hurry. There is no time to wait. You are all bound for perdition," he assured her, cheerfully.

"Perdition then! I won't do it." Temptation number two, for Pamina.

"Very well, it is your time to die!" Monostatos cried, and proceeded to kill her, but Sarastro entered just in time to encourage her.

"Indeed it is not – your schedule is wrong, Monostatos," Sarastro assured him.

"I must look after the mother, then, since the daughter has escaped me," Monostatos remarked, comforting himself as well as he could.

"Oh don't chastise my mother," Pamina cried.

"A little chastising won't hurt her in the least," Sarastro assured her. "I know all about how she prowls around here, and if only Tamino resists his temptations, you will be united and your mother sent back to her own domain where she belongs. If he survives the ordeals we have set before him, he will deserve to marry an orphan." All this was doubtless true, but it annoyed Pamina exceedingly. As soon as Sarastro had sung of the advantages of living in so delightful a place as the temple, he disappeared, not in the usual way, but by walking off, and the scene changed.

Scene IIITamino and the speaker who accompanied the priests and talked for them were in a large hall, and Papageno was there also.

"You are again to be left here alone; and I caution ye to be silent," the speaker advised as he went out.

The second priest said:

"Papageno, whoever breaks the silence here, brings down thunder and lightning upon himself." He, too, went out.

"That's pleasant," Papageno remarked.

"You are only to think it is pleasant – not to mention it," Tamino cautioned. Meantime, Papageno, who couldn't hold his tongue to save his life, grew thirsty. And he no sooner became aware of it, than an old woman entered with a cup of water.

"Is that for me?" he asked.

"Yes, my love," she replied, and Papageno drank it.

"Well, next time when you wish to quench my thirst you must bring something besides water – don't forget. Sit down here, old lady, it is confoundedly dull," the irrepressible Papageno said, and the old lady sat. "How old are you, anyway?"

"Just eighteen years and two minutes," she answered.

"Um – it is the two minutes that does it, I suppose," Papageno reflected, looking at her critically.

"Does anybody love you?" he asked, by way of satisfying his curiosity.

"Certainly – his name is Papageno."

"The deuce you say? Well, well, I never would have thought it of myself. Well, what's your name, mam?" but just as the old lady was about to answer, the thunder boomed and off she rushed.

"Oh, heaven! I'll never speak another word," Papageno cried. He had no sooner taken that excellent resolution than the three Genii entered bearing a table loaded with good things to eat. They also brought the flute and the chime of bells.

"Now, eat, drink, and be merry, and a better time shall follow," they said, and then they disappeared.

"Well, well, this is something like it," Papageno said, beginning at once to obey commands, but Tamino began to play upon the flute.

"All right; all right! You be the orchestra and I'll take care of the table d'hôte," he said, very well satisfied; but at that instant Pamina appeared.

She no sooner began to talk to Tamino than he motioned her away. He was a youth of unheard-of fortitude.

"This is worse than death," she said. She found herself waved away again. Tamino was thoroughly proof against temptation.

Then Pamina sang for him, and she had a very good voice. Meantime, Papageno was sufficiently occupied to be quiet, but he had to call attention to his virtues. When he asked if he had not been amazingly still, there was a flourish of trumpets. Tamino signed for Papageno to go.

"No, you go first!" Tamino only repeated his gesture.

"Very well, very well, I'll go first – but what's to be done with us now?" Tamino only pointed to heaven, which was very depressing to one of Papageno's temperament.

"You think so!" Papageno asked. "If it is to be anything like that, I think it more likely to be a roasting. No matter!" Nothing mattered any longer to Papageno, and so he went out as Tamino desired, and the scene changed.

Scene IVSarastro and his priests were in a vault underneath one of the temples. There they sang of Tamino's wonderful fortitude and then said:

"Let him appear!" And so he did. "Now, Tamino, you have been a brave man till now; but there are two perilous trials awaiting you, and if you go through them well – " They didn't exactly promise that all should be plain sailing after that, but they led the youth to infer as much, which encouraged him. "Lead in Pamina," the order then was given, and she was led in.

"Now, Pamina, this youth is to bid thee a last farewell," Sarastro said.

Pamina was about to throw herself into her lover's arms, but with amazing self-control Tamino told her once more to "Stand back." As that had gone so very well, Sarastro assured them they were to meet again.

"I'll bear whatever the gods put upon me," the patient youth replied.

Then he said farewell and went out, while Papageno (who if he ever did get to Heaven, would surely do so by hanging on to Tamino's immaculate coat-tail) ran after him, declaring that he would follow him forever – and not talk. But it thundered again, and Papageno shrunk all up.

Then, while the speaker chided him for not being above his station, Papageno said that the only thing he really wanted in this world or the next was a glass of wine: he thought it would encourage him.

"Oh, well, you can have that," the speaker assured him, and immediately the glass of wine rose through the floor. But he had no sooner drunk that than he cried out that he experienced a most thrilling sensation about his heart. It turned out to be love; just love! So at once, the matter being explained to him, he took his chime of bells, played, and sang of what he felt. The moment he had fully expressed himself, the old water lady came in.

"Here I am, my angel," she said.

"Good! You are much better than nobody," Papageno declared.

"Then swear you'll be forever true," she urged.

"Certainly – since there is no other way out of it." And it was no sooner said than the old lady became a most entrancing young one, about eighteen years old.

"Well, may I never doubt a woman when she tells me her age again!" Papageno muttered, staring at her. As he was about to embrace her, the speaker shouted:

"Away; he isn't worthy of you." This left Papageno in a nice fix, and both he and the girl were led away as the Genii appeared.

The Genii began to sing that Pamina had gone demented, and no wonder. She almost at once proved that this was true, by coming in carrying a dagger; and she made a pass at the whole lot of them. No one could blame her. She thought each of them was Tamino.

"She's had too much trouble," the penetrating Genii declared among themselves. "And now we'll set her right." They were about to do so when she undertook to stab herself, but they interfered and told her she mustn't.

"What if Tamino should hear you! It would make him feel very badly," they remonstrated. At once she became all right again.

"Is he alive? Just let me look at him, and I'll be encouraged to wait awhile." So they took her away to see Tamino.

Then two men dressed in armour came in and said:

He who would wander on this path of tears and toiling,Needs water, fire, and earth for his assoiling,which means nothing in particular. Although "assoiling" is an excellent old English word.

Then Tamino and Pamina were heard calling to each other. She entreated him not to fly from her, and he didn't know what he had better do about it, but the matter was arranged by somebody opening some gates and the lovers at once embraced. They were perfectly happy, and there seemed to be a mutual understanding between them that they could wander forth together. They did so, and wandered at once into a mountain of fire, while Tamino played entertainingly upon his flute. Soon they wandered out of the fire, and embraced at leisure. Then they wandered into the water, and Tamino began again to play upon his flute, the water keeping clear of the holes in a wonderful way. After they got out of the woods – the water, rather, – they embraced as usual, and the gates of the temple were thrown open and they saw a sort of Fourth-of-July going on within. Everything was very bright and high-coloured. This would seem to indicate that their trials were over and they were to have their reward. Then the scene changed.

Scene VPapageno was playing in a garden, all the while calling to his Papagena. He was really mourning for his lost love, and so he took the rope which he used as a girdle and decided to hang himself. Then the Genii, whose business it seemed to be to drive lovers to suicide and then rescue them just before life was extinct, rushed in and told him he need not go to the length – of his rope.

"Just ring your bells," they advised him; and he instantly tried the same old effect. He had no sooner rung for her than she came – the lovely Papagena! They sang a joyous chorus of "pa-pa-pa-pa" for eight pages and then the Queen of the Night and Monostatos, finding that matters were going too well, appeared. They had come to steal the temple.

"If I really get away with that temple, Pamina shall be yours," she promised Monostatos, – which would seem to leave Pamina safe enough, if the circumstances were ordinary. Nevertheless it thundered again. Nobody in the opera could seem to stand that. The Queen had her three ladies with her, but by this time one might almost conclude that they were no ladies at all. The thunder became very bad indeed, and the retinue, Monostatos, and the Queen sank below, and in their stead Sarastro, Pamina, and Tamino appeared with all the priests, and the storm gave way to a fine day.

Immediately after that, nothing at all happened.

SIR ARTHUR SULLIVAN

SIR ARTHUR SULLIVAN was a man of many musical moods and varied performances, yet his surest fame, at present, rests upon his comic operas.

Perhaps this is because he and his workfellow, Gilbert, were pioneers in making a totally new kind of comic opera. "Pinafore" may not be the best of these works, "Mikado" may be better; but "Pinafore" was the first of the satires upon certain institutions, social and political, which delighted the English-speaking world.

Music and words never have seemed better wedded than in the comic operas of Gilbert and Sullivan. The music is always graceful, gracious, piquant, and gaily fascinating. The story has no purpose but that of carrying some satirical idea, and the satire is never bitter, always playful.

Sullivan's versatility was remarkable, his work ranging from "grave to gay, from lively to severe," and his was a genius that developed in his extreme youth. Many anecdotes are told of this brilliant composer, and all of them seem to illustrate a practical and resourceful mind, while they show little of the eccentricity that is supposed to belong to genius. It was Sir Arthur Sullivan who first popularized Schumann in England. Potter, head of the Royal Academy in London in 1861, had known Beethoven well, and had never been converted to a love of music less great than his – nor was his taste very catholic – and he continually regretted Sullivan's championship of Schumann's music. But one day Sullivan, suspecting the academician didn't know what he was talking about, asked him point-blank if he had ever heard any of the music he so strongly condemned. Potter admitted that he hadn't. Whereupon Sullivan said, "Then play some of Schumann with me, Mr. Potter," and, having done so, Potter "blindly worshipped" Schumann even after.

Frederick Crowest tells this story in his "Musicians' Wit, Humour, and Anecdote":

"The late Sir Arthur Sullivan, in the struggling years of his career, once showed great presence of mind, which saved the entire breakdown of a performance of 'Faust.' In the midst of the church scene, the wire connecting the pedal under Costa's foot with the metronome stick at the organ, broke. Costa was the conductor. In the concerted music this meant disaster, as the organist could hear nothing but his own instrument. Quick as thought, while he was playing the introductory solo, Sullivan called a stage hand. 'Go,' he said, 'and tell Mr. Costa that the wire is broken, and that he is to keep his ears open and follow me.' No sooner had the man flown to deliver his message than the full meaning of the words flashed upon Sullivan. What would Costa, autocratic, severe, and quick to take offence, say to such a message delivered by a stage hand? The scene, however, proceeded successfully, and at the end Sullivan went, nervously enough, to tender his apologies to his chief. Costa, implacable as he was, had a strong sense of justice, and the great conductor never forgot the signal service his young friend had rendered him by preventing a horrible fiasco."

There are numberless stories of his suiting his composition to erratic themes. Beverley had painted borders for a woodland scene. Sullivan liked the work and complimented Beverley, who immediately said: "Yes, and if you could compose something to fit it now." Instantly, Sullivan, who was at the organ, composed a score within a few minutes which enraptured the painter and which "fitted" his borders.

Again: A dance was required at a moment's notice for a second danseuse, and the stage manager was distracted. "You must make something at once, Sullivan," he said. "But," replied the composer, "I haven't even seen the girl. I don't know her style or what she needs." However, the stage manager sent the dancer to speak with Sullivan, and presently he called out: "I've arranged it all. This is exactly what she wants: Tiddle-iddle-um, tiddle-iddle-um, rum-tirum-tirum – sixteen bars of that; then: rum-tum-rum-tum – heavy you know – " and in ten minutes the dance was made and ready for rehearsal.

H.M.S. 2 “PINAFORE”

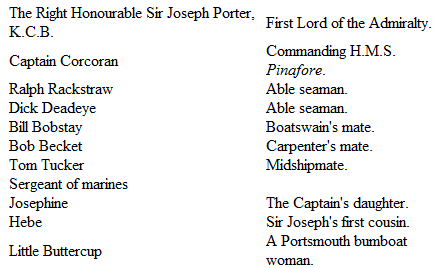

First Lord's sisters, his cousins, his aunts, sailors, marines, etc.

The story takes place on the quarterdeck of H.M.S. Pinafore, off Portsmouth.

Composer: Sir Arthur Sullivan. Author: W.S. Gilbert.

ACT IOn the quarterdeck of the good ship Pinafore, along about noon, on a brilliant sunny day, the sailors, in charge of the Boatswain, are polishing up the brasswork of the ship, splicing rope, and doing general housekeeping, for the excellent reason that the high cockalorum of the navy – the Admiral, Sir Joseph Porter – together with all his sisters and his cousins and his aunts, is expected on board about luncheon time. When an Admiral goes visiting either on land or sea, there are certain to be "doings," and there are going to be mighty big doings on this occasion. If sailors were ever proud of a ship, those of the Pinafore are they. The Pinafore was, in fact, the dandiest thing afloat. No sailor ever did anything without singing about it, and as they "Heave ho, my hearties" – or whatever it is sailors do – they sing their minds about the Pinafore in a way to leave no mistake as to their opinions.

We sail the ocean blue,And our saucy ship's a beauty.We're sober men and true,And attentive to our duty.When the balls whistle free,O'er the bright blue sea,We stand to our guns all day.When at anchor we ride,On the Portsmouth tide,We've plenty of time for play – Ahoy, Ahoy!And then, while they are polishing at top speed, on board scrambles Little Buttercup. Naturally, being a bumboat woman, she had her basket on her arm.

"Little Buttercup!" the crew shouts; they know her well on pay-day.

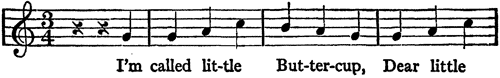

"Yes – here's an end at last of all privation," she assures them, spreading out her wares, and this ridiculous "little" Buttercup sings:

[Listen]

I'm called little Buttercup,Dear little Buttercup,Though I could never tell why,But still I'm called Buttercup,Poor little Buttercup,Sweet little Buttercup I.I've snuff and tobaccy,And excellent jacky;I've scissors and watches and knives.I've ribbons and lacesTo set off the facesOf pretty young sweethearts and wives.I've treacle and toffee,I've tea and I've coffee,Soft tommy and succulent chops,I've chickens and conies,I've pretty polonies,And excellent peppermint drops —

which would imply that Little Buttercup might supply on demand anything from a wrought-iron gate to a paper of toothpicks.

"Well, Little Buttercup, you're the rosiest and roundest beauty in all the navy, and we're always glad to see you."

"The rosiest and roundest, eh? Did it ever occur to you that beneath my gay exterior a fearful tragedy may be brewing?" she asks in her most mysterious tones.

"We never thought of that," the Boatswain reflects.

"I have thought of it often," a growling voice interrupts, and everybody looks up to see Dick Deadeye. Dick is a darling, if appearances count. He was named Deadeye because he had a dead-eye, and he is about as sinister and ominous a creature as ever made a comic opera shiver.

"You look as if you had often thought of it," somebody retorts, as all move away from him in a manner which shows Dick to be no favourite.

"You don't care much about me, I should say?" Dick offers, looking about at his mates.

"Well, now, honest, Dick, ye can't just expect to be loved, with such a name as Deadeye."

Little Buttercup, who has been offering her wares to the other sailors, now observes a very good-looking chap coming on deck.

"Who is that youth, whose faltering feet with difficulty bear him on his course?" Buttercup asks – which is quite ridiculous, if you only dissect her language! Those "faltering feet which with difficulty bear him on his course" belong to Ralph Rackstraw, who is about the most dashing sailor in the fleet. The moment Buttercup hears his name, she gasps to music:

"Remorse, remorse," which is very, very funny indeed, since there appears to be nothing at all remarkable or remorseful about Ralph Rackstraw. But Ralph immediately begins to sing about a nightingale and a moon's bright ray and several other things most inappropriate to the occasion, and winds up with "He sang, Ah, well-a-day," in the most pathetic manner. The other sailors repeat after him, "Ah, well-a-day," also in a very pathetic manner, and Ralph thanks them in the politest, most heartbroken manner, by saying:

I know the value of a kindly chorus,But choruses yield little consolationWhen we have pain and sorrow, too, before us!I love, and love, alas! above my station.Which lets the cat out of the bag, at last! "He loves above his station!" Buttercup sighs, and pretty much the entire navy sighs. Those sailors are very sentimental chaps, very! – They are supposed to have a sweetheart in every port, though, to be sure, none of them are likely be above anybody's station. But their sighs are an encouragement to Ralph to tell all about his sweetheart, and he immediately does so. He sings rapturously of her appearance and of how unworthy he is. The crew nearly melts to tears during the recital. Just as Ralph has revealed that his love is Josephine, the Captain's daughter, and all the crew but Dick Deadeye are about to burst out weeping, the Captain puts in an appearance.

"My gallant crew, – good morning!" he says amiably, in that condescending manner quite to be expected of a Captain. He inquires nicely about the general health of the crew, and announces that he is in reasonable health himself. Then with the best intentions in the world, he begins to throw bouquets at himself:

I am the Captain of the Pinafore,he announces, and the crew returns:

And a right good Captain too.You're very, very good,And be it understood,I command a right good crew,he assures them.

Tho' related to a peer,I can hand, reef and steer,Or ship a selvagee;I'm never known to quailAt the fury of a gale, —And I'm never, never sick at sea!But this is altogether too much. The crew haven't summered and wintered with this gallant Captain for nothing.

"What, never?" they admonish him.

"No, – never."

"What! – NEVER?" and there is no mistaking their emphasis.

"Oh, well – hardly ever!" he admits, trimming his statement a little: and thus harmony is restored. Now when he has thus agreeably said good morning to his crew, they leave him to meditate alone, and no one but Little Buttercup remains. For some reason she perceives that the Captain is sad. He doesn't look it, but the most comic moments in comic opera are likely enough to be the saddest. Hence Little Buttercup reminds him that she is a mother (she doesn't look it) and therefore to be confided in.