Полная версия

The Pavlova Omnibus

New Zealand political institutions are like any other local industry. The plant is small, outdated and orginally imported, though the rulers have tinkered with it, scrapping the Legislative Council packing room here, adding an Ombudsman machine there. Production is strictly for the home market. And it is heavily protected, otherwise Mr Lee Kuan Yew might take over and run the country on a part-time basis from his head office in Singapore. The real difference from similar industries overseas is the way the local staff, the ‘politicians’, run the plant.

Genus Politicus New Zealandiensis is not under flora so he must come under fauna. He is not a unique element in the local fauna, though the type is rapidly becoming extinct overseas, where it has been hunted down and pushed out by ruthless professionals. The British think of their politicians as an élite distinguished by ability and intellect. The Americans think of their politicians as corrupt; the honest politician is one who, when bought, stays bought. In New Zealand honesty is the norm, a testimony to lack of imagination and the unsaleability of the product rather than superior virtue. Politicians are essentially the ordinary bloke. The prime requirement is neither intellect nor ability but that of being (or appearing to be) a good bloke. In politics the good bloke syndrome finds its highest expression. The best politician is the one who blends most harmoniously into the Kiwi background.

In each party, selection of candidates is in the hands of party members who can be guaranteed to pick people like themselves. Like the selector, the candidate must live in the electorate so they’ll know if he looks after his garden. He must have a wife whose looks and social poise won’t make the homeliest selector feel threatened. Children and a dog are desirable for featuring on householder pamphlets and press publicity (in rural electorates add one more child and leave the dog off). He should preferably have attracted attention by his assiduous committee joining, by activity for appropriately wholesome causes, and by being seen at the RSA He should display no hint of any abnormality in education, of superior intellect or peculiar sexual inclination. The unusual frightens New Zealanders; the like reassures them. They will seek it out and stick to it with determination. Abnormalities should be disguised by frenzied housebuilding, concreting, or if possible, breaking-in of land. It is advisable to have had several jobs. This is known as valuable experience.[*]

Imagine the speech a locally born John F. Kennedy would have to make to get past the National Party selection meeting in Hawke’s Bay:

‘Ladies and Gentlemen. Since my family bought—er—settled in this electorate there have been wholly unfounded rumours that I am attempting to buy my way into politics. I give the lie to these allegations. Why have none of the allegators been man enough to come into the open? My father played as a child in the Karangahape Road. All he has he had to work hard for and he had to provide for a large family—in fact we could do with more of his kind of spirit—I sometimes think we’re getting too dependent on the State to do things for us rather than doing them for ourselves.

‘My father didn’t believe in this new-fangled play-way stuff. He thought that sparing the rod was spoiling the child—and though I resented it at the time I think, looking back on it, he was right. At twelve I was walking barefoot behind the plough on one of—er—on the family farm. We were a large family so I had to go away to school, but at Christ’s College District High School I was never one for book learning. Perhaps I spent too much time on the rugby field.

‘Then my father had to go to England on business. Though I didn’t want to go, at least it did show me how lucky we are in New Zealand. I can tell you, I couldn’t get back quickly enough. As for my war service—well it’s not something I often talk about. I had to lie about my age, I’m afraid, to get into the army, but I’ll never forget the mates I made in those days and I’m sure my injuries haven’t affected my ability to do my job in any way—in fact they’ve helped me to understand the meaning of suffering. It’s something I hope we never have to go through again, but if we have to, we’ll do our bit.

‘I wasn’t fortunate enough to marry one of our New Zealand girls. But my wife’s learning our ways—she made her first scones last week and she’s asked me to say that she hopes you’ll drop in any time for a chat, just as soon as I’ve concreted the drive. When we’re settled in our new palace—er—place, she’ll be along to the Women’s Division dressmaking circle.

‘That’s all I want to say. I’m not used to making speeches—and right now I’d sooner be out in the paddock. But then I sometimes think we’ve already got enough over-educated know-alls in politics. What we need is a bit more trust and integrity. Perhaps I’m a bit old-fashioned, but it’s not a glib tongue that Hawke’s Bay needs but someone with a stake in the electorate and who knows what it needs. And I hope you’ll tell me.’

As a process of choosing, say, university staff, or directors of Dalgety Loan, this would be ridiculous. For choosing the men who decide on the fate of the universities and influence the destinies of Dalgety Loan, it is admirable. Politician is the only job in New Zealand for which neither qualifications nor training are necessary.

The job is essentially the same as that of the television frontman. In television someone else takes the decisions, decides the questions, arranges the discussion. The frontman only seems to be in charge.

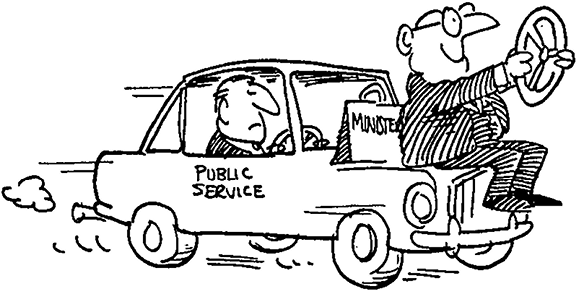

So, in politics, the member of Parliament is a middle man. In power he explains, justifies and interprets the decisions of the public servants to the man in the street. In opposition he asks of the public servants the questions that the man in the street is interested in. Both jobs can best be done if the MP himself is either the man in the street or not long off it. Administrators need protective cover. It might as well be realistic.

Once elected, the honourable member (for he is always given the benefit of the doubt) has many interesting, although optional, things to do. The ugly, some of the unconcealably stupid, and those who have the misfortune not to get on with their party leader, become backbenchers. Their job is to speak. In Parliament they are reverse somnambulists, talking in other people’s sleep. They discuss party preoccupations and the epoch-making concerns of their constituents: Mr May (at question time)—’When does the Railways Department intend to paint the Tawa station and overbridge which are at present in a dilapidated condition?’ Such a question allows Henry to sit back, confident that he can do no more to change the course of destiny, short of getting out his own paintbrush. The speeches continue (and are often repeated) outside Parliament, where M.Ps are expected to open fêtes (some of them worse than death), church bazaars, post offices, schools, annual general meetings and all those other things that Brian Edwards, Selwyn Toogood, or any other stray television celebrities are too busy to do.

The remainder of the M.Ps go on to higher things. New Zealand is an egalitarian community and anyone can get to the top; which is more of a threat than a promise. There are no formal requirements, though the constitution provides that National shall be led by a socialist and the Labour Party by a Tory. Neither the People’s Walter nor the People’s Norm can be deepest red, whatever they’ve done to the party’s martyred dead (an obscure and somewhat tasteless reference to Arnold Nordmeyer, expelled from the Labour leadership when he was discovered to have a degree).

Outside these guidelines, there are no curbs to the full and happy life a minister can lead. Those who are out of hospital can travel or meet endless deputations. The minister’s job carries with it immense dignity as well as someone more literate than himself to write his speeches. The one thing he must not do is to take decisions. These must be taken for him by his departmental officials and his party caucus. His job is to interpret one lot of these decision-makers to the other and defend both to the public. Like the backbencher he is a middleman, only he works wholesale rather than retail.

A minister also has the job of ritual soothsayer to the nation. The prime task of the politician in New Zealand is to tell the people what they want to hear. Not for him the stern imperatives of Churchillian oratory. He prefers the ritual incantation of platitudes, strung together by a stream of consciousness technique discovered well before James Joyce learnt how to write without fullstops. Richard John Seddon would stump the country telling each little community that it would have the roads, the bridges, the loans and the public works which in those simple days constituted happiness. Then he would move on to the next settlement to promise them exactly the same things. Those days are gone. The Press Association and the television now tell the whole country what is promised to each particular part. In any case, public taste has changed. Now we like slices of reassurance or pie in the sky. Policies, like butter, need spreading. So speechmaking becomes topdressing of platitudes, promises and reassurances.

Since the two last ones are in comparatively short supply, politicians have to pad them out and dilute them by energetically advocating policies which no one in his right mind would oppose. Politicians who can’t tell the difference between the Apocrypha and the New Zealand Woman’s Weekly compete to defend the Deity and the Christian religion against all sorts of dark threats. Time and energy are devoted to protecting wholesomeness, motherhood and the family, as though all three were threatened with overwhelming catastrophe from the New Zealand University Students’ Association.

Like the Mafia, politicians work in a gang, a caucus nostra. Ever moderate, New Zealanders have compromised between the extremes of one-party and two-party systems which characterise less happy lands overseas. They have opted for a two-party system in which each party has the same policy. One party governs and the other opposes, both intermittently change round, and nothing happens. This is the real action, but there are all sorts of sideshows at the fair.

Moving, in the fashion of any good Labour man as he grows older, from left to right, let me begin with the Marxists. They owe more to Groucho than to Karl. New Zealand’s communists have now split up into fifty-seven different varieties, which is two varieties more than the actual number of communists. In Dunedin, being closest to Russia, there lives a group of Marxists still as dedicated to Comrade Stalin as others in the town are to Bonnie Prince Charlie. There they sit perfectly preserved, like everyone else in that historical deep freeze called Otago, in the attitudes of the 1930s. Further north, in Auckland, Comrade Mao is more fashionable. Indeed the Communist Parties of China and New Zealand have issued at least one joint statement, a boost to the Chinese self-confidence which may have led directly to the Vietnam war.

There’s no need to fear any of our resident concert party of communists as a revolutionary threat. In the first place, i.e. Auckland, they devote more time and effort to opposing each other than to subverting capitalism. In the second place, whatever energy and time they have left over is consumed by publishing pamphlets and periodicals which nobody reads and putting up election candidates that nobody votes for; democracy is the opium of the Marxists. Expenditure on electioneering works out at over two dollars for every vote received. At that rate they couldn’t afford to win.

In any case Marxists are a small and dwindling band. The increasing misery of the proletariat somehow doesn’t apply in a country where they are inconsiderate enough to buy more cars and washing machines every year. The energies of the young Left are going into the Progressive Youth Movement. Yet a spectre will always remain to haunt us. If communism did not exist the National Party would have to invent it.

Panning right, across the spectrum, brings us to a plethora of mini-parties. Only inertia and laziness prevent New Zealand from developing as many parties as there are people. It’s as easy to form a party as to buy the New Zealand Herald and twice as interesting. The number of parties contesting the elections increases as the vote goes down. In 1969 puzzled electors had to choose between fifteen parties with no Consumer Council to nominate a best buy. In 1972 everyone was keeping the children amused by letting them stand for Parliament.

There are also maxi-mini-parties. One such is the Country Party, which intermittently makes an appearance. Country parties come and go, the rut remains the same. In each case the objective is to bring Downie Stewart back to power by constitutional means. Liberal parties also flourish and die, usually with policies of hanging, flogging, ending mollycoddling and other such liberal nostrums. The Constitutional Society, also known as the political arm of the New Zealand Who’s Who, long advocated the restoration of the nineteenth century. The Mad Hatter’s Tea Party advocates the restoration of Mickey Mouse to the throne.

Finally there are the provincial separatist movements. They should by rights be strongest in Nelson which has been completely cut off from the rest of the South Island for twenty years without anyone noticing. However, the National Government clearly existed only to persecute Nelson by abolishing cotton mills, stopping railway building (Nelson has a notional railway—something often described in other parts of the country as a road) and other tortures. As a result all separatist passion in the province is channelled into the Labour Party. Otago is different. The Home Rule for Otago Movement would be very powerful, were it not for the fact that the Otago Daily Times (All the News that Fits, We Print) dare not back such a movement for fear of producing a Labour Provincial Council, with Mrs McMillan as first president and closing the ODT as first policy.

This brings us to Social Credit, which campaigns to bring the pleasure of overdrafts to people without bank accounts. This theory of the continuous creation of credit was invented by an English engineer, Major Douglas. He omitted to patent his invention and though the Japanese didn’t take it up, New Zealand did. The Social Credit Political League, present medium for the message, periodically splits, believing in the continuous creation of parties. It blends zeal for the crusade with a feeling of persecution, desire to illuminate mankind with a sense of alienation from it. In 1954 the league approached politics with all the charm and friendliness of Elliot Ness meeting the Mafia. Now it has compromised; the A:B theorem no longer plays on the Social Credit hit parade. About the only present use for the old economic doctrines is to provide the justification for lavish political promises. At election times Labour and National both go for the laxative image, promising to get New Zealand moving again (Labour, 1966) or to keep New Zealand on the move (National, 1969). Social Credit projects a positive deluge of benefits. It’s also an ideal party for New Zealand, for overseas debt has made it a country run on hire purchase, a never-never land.

The league is happiest out of Parliament so that it need not take sides; the electorate has usually been happy to accept this interpretation of the league’s best interest. Yet Mr Cracknell, its one MP, couldn’t tell the difference between Parliament and the Northland Harbour Board in his three-year term. In this period he attended Parliament whenever he could get to Wellington and held his caucus meetings in the telephone booth in the lobby, though manifesting an unfortunate reluctance to be bound by caucus decisions. He was then ejected. The good electors of ‘Northland were voting not for him or his party but for a far higher and more noble cause: marginal seat status. Marginal seat status is provincial New Zealand’s answer to the twentieth century. Inconsiderate economic forces pull development, industry and skills towards the larger centres of population (a euphemism for Auckland). So the provincial towns must vote marginal to keep up the supply of post offices, Government Life offices, coal-fired power stations, and airports. Northland’s reward for its flirtation with Mr Cracknel I was the most lavish programme of road building in the country.

Now for the big league. National, which traditionally runs the country, is the most able party in the world, including in its ranks more ex-Prime Ministers than any other party. They include Sir Keith Holyoake, the amateur version of Robert Menzies, whose resignation was accepted before it was discovered that he didn’t really mean it, Jack Marshall, who proved to be the political version of the Princes in the Tower, and Robert Muldoon, who elected himself leader in 1960 and was ratified by caucus in 1974. This trend to disposable leaders is not followed by Labour, led by Norman Kirk, who is believed to be the largest Labour Party leader in the Southern Hemisphere. Opposition isn’t a satisfying role, though the leader has almost as much power as Brian Edwards, so, to prevent the Labour Party members from becoming sullen, discouraged and disillusioned (or more so than usual), they are allowed to make the political running in the year and a half before the election and to carry all before them in the actual election campaign. Then, to set the balance right, the electors tramp out to the polls and keep National in power, preferably by as fine a majority as possible. This guarantees that the party won’t dare to implement its policies. The election is usually a mere formality. The National Party pays for opinion polls so it knows the result in advance and judges its policy accordingly. When certain it is going to win (as in 1966) it will denounce all Labour’s policies in advance of the poll and then implement them quietly afterwards. When more doubtful (as in 1969) it will go in for really bubonic plagiarism and implement Labour polices in advance. When it knows it’s lost, it elects Jack Marshall as leader.

This situation provides useful roles for almost everybody. The Labour Party is kept happy and busy exhausting itself in the continuous pursuit of new policies for National to steal, and in continuously renovating itself. Of course Labour does from time to time hit on policies which National seems reluctant to steal. Labour then becomes so worried about this section of its manifesto that it is hardly mentioned. As for the Labour Party Youth Movement (also known as the Princes Street Branch or Dr Michael Bassett) it has a useful role in preaching the need for a policy relevant to the sixties, the seventies or whatever decade the party finds itself in. Finally, generations of political scientists can republish their ‘Whither Labour?’ articles at regular intervals.

From time to time even this surfeit of goodies is not enough. Then Divine Providence (Treasury code name for the IMF) produces an economic crisis. Ministers cry, ‘Do not adjust your government, the world is at fault,’ but they look tired and say it lamely, so adversity stirs the electors into action and Labour comes to office. The party then incurs enough unpopularity in dealing with the crisis to guarantee that it remains in opposition for a further decade or two. This process is known as Nash’s law.

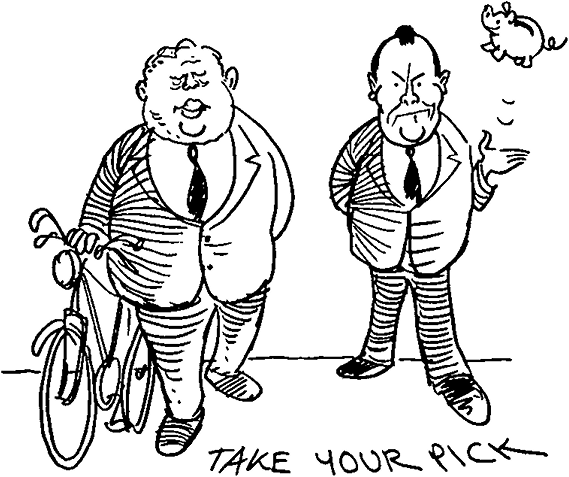

Every nation has its divine mystery, its central enigma. In Britain they puzzle over telling New Stork from Butter. Because New Zealanders are better educated and not allowed margarine they worry whether there is any difference between the political parties. Don’t listen to the cynics. They may be the country’s largest religious denomination but they are wrong. It is possible to tell the difference between Political Brand X and Brand XX. Both parties have policies. Both parties are honourable about implementing them—even when they would be better advised not to. Both parties behave differently because of conditioned reflexes. When things go well (that’s election year) it doesn’t really matter which party is in power. When things go badly (that’s the year after the election) each party will choose different ways of getting at you for the over-spending they had encouraged you to go in for only a few months back.

You must first distinguish between Government and Opposition. This is easy because every member of a party team makes the same speech. The master speech is prepared by the party research officer who sits in a basement room in Parliament Building supplying speech notes to members.

Taking the Government members’ omnipurpose speech first, the notes for this read:

Expression of pleasure at being in ………… and recollection of excitement with which speaker first heard his great-aunt recount the details of her first (and only) visit in 1932.

Passing mention of deity-royal family—importance of family life, personal cleanliness and, if time allows, regular brushing of teeth.

Expression of faith in New Zealand’s peculiar destiny, high standard of living and intrinsic ability of New Zealand people.

Need for tried and trusted leadership—and necessity of experience in face of looming problem of Common Market, pollution, permissive society or long-haired larrikins depending on the I.Q. of the audience. Expression of confidence in leader, possibly combined with statement that television does not do him justice. Mention of Deputy Prime Minister. This should not be too lavish lest it might anger Prime Minister and indicate a taking of sides in a leadership struggle.

List of things Government will do and benefits to come followed by refusal to buy votes and warning against promises (easy, glittery or dazzling).

Increase in exports (change figures from volume to value as circumstances require).

Rise in standard of living (quoting figures for cars, washing machines, fridges or Feltex carpets as necessary).

Increase in population—with discreet hint of Government virility and heterosexuality.

Diffident voicing of doubts about loyalty, competence, associates, and manliness of Opposition.

Quick mention of importance of environment and dangers of pollution to show awareness of problem (rephrase if any other problem becomes fashionable).

Quotation of statistics (seasonally corrected, base date for National, 1972 for Labour) proving that immigration to Australia, cost of living, and infant mortality all increasing at slower rate than under previous governments.

Peroration expressing confidence in future if leadership unchanged, rebuttal of unnamed critics of Prime Minister, and praise of wisdom of New Zealand people in choosing speaker and his party.

Government members can’t be too critical and they cannot claim credit for everything without being accused of immodesty. The Opposition has more latitude. The basic framework of their speech, as prepared by their party research officer, follows:

Expression of pleasure at being in ………… and moving recollection of help given to great uncle who passed through there looking for work in 1932.

Concern about way in which standard of living and welfare services in New Zealand are falling behind America, Australia, Kuwait or Venezuela as appropriate.

Comparison of annual holidays, hours of work, overtime rates in New Zealand with Scandinavia, America, Paraguay or Uruguay as appropriate.

Expression of concern at increase in crime rate, gang rapes and illegitimatcy, together with hint that Government is either responsible in some unspecified fashion or soft in some unspecified way (or area) . Need for law and order—with mention of good work done by police force in difficult circumstances.