Полная версия

The Pavlova Omnibus

The universities have several advantages. Because of the tradition of going to the nearest university rather than the best, a high proportion of students live at home. Thus lots of them concentrate money on essentials, rather than lavishing it on accommodation. Universities are open to a larger proportion of the population than is the case in Britain: entry conditions are easier. Everyone has the right to fail once they’re 21 and part-time study provides a people’s democracy degree.

Unfortunately these New Zealand institutions are manned by an alien fifth column. One third of the staff come from overseas, mainly from Britain, where universities are very different creatures. The most able British academics wouldn’t dream of coming to a country they regard as an academic outer Siberia. In 1959 I would have been hard put to get a job as assistant janitor at Battersea Polytechnic. In New Zealand I was a full lecturer. Promotion is so rapid that most people finish up as Associate Professor. Unfortunately their inability to get jobs in British universities makes importees more anxious and assertive about a university status they hold so tenuously.

A high proportion of the natives have also been corrupted by postgraduate training overseas. The most able are lost, unable to stand the loneliness of the long-distance intellectual and the lack of stimulus and excitement. The only section genuinely appreciative of the country’s traditions is the small but increasing number of Americans, bomb refugees, Vietnam protesters and people unwilling to buy a secondhand America from President Nixon. Since many of them are busily building bomb shelters, lobbying for peace or supporting student revolt they are collectively dismissed as insane, politically unstable or both.

With this exception, university staffs spend their time complaining because their intellectual gifts are not recognised by the community in general and Mr Muldoon in particular, lamenting at the government’s failure to pay them as much as American and British academics, and airing their highly developed God complexes on their students. The only way in which they resemble good New Zealanders is their nine to five work habits and their quiet domesticity in the better suburbs like Cashmere, of which the University of Canterbury poet said, ‘I will lift up mine eyes to the hills, whence cometh my staff’.

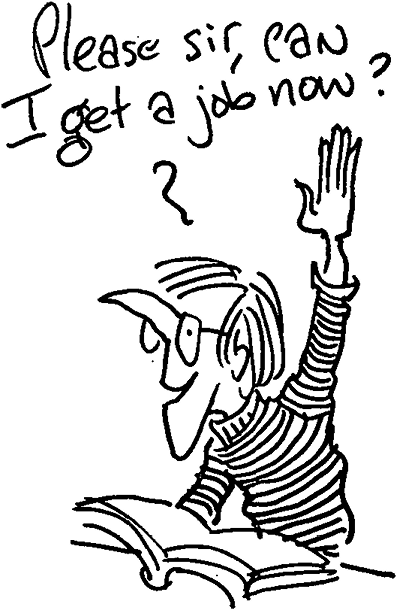

The students are another ground for staff dissatisfaction. They take the books out of the library, make the place look untidy, drive suspiciously close to the staff when homeward bound. The staff want to teach only the best but have to drop their artificial pearls in front of swine. The staff want students to be passionately interested in their subject; the students want a meal ticket and will put together any kit-set structure of Wisdom I, Taste and Discrimination II and Sense and Sensibility III which puts them as quickly as possible on to the labour market. The staff want excitement and discussion from students whose schooling has prepared them only to take down sacred texts. Say ‘Good morning’ to a class of British students and they’ll reply, ‘Good morning, Comrade’. Say it in New Zealand and they’ll take it down. The lecturer’s approach has to be to say what he’s going to say, say it, then recapitulate—a lesson brought home to me in my first lecture. With a naive enthusiasm for Socratic techniques, I outlined the case of those who thought the gentry rose from 1540-1640, then the counter case against the self-raising gentry, and invited them to choose. I was surrounded by an anxious group of students asking, ‘But what do you think?’ Here was the key to success and the line that would come back to me, with some deterioration in the grammar and style, in exam papers.

Staff see students as a necessary nuisance and a numerical argument for increased finance for their department. For university authorities the students are another problem. University officials want a quiet life, an undisturbed production flow of books, articles and graduates, and a happy local community which will hand over large sums of money because its clean, well scrubbed students are almost as big a tourist attraction as the botanical gardens. Unfortunately the raw material is volatile: girls get pregnant, students demonstrate instead of leaving it to lab assistants. Even the capping celebrations, whose real purpose is to give lawyers a week they can talk about for the rest of their lives, get embarrassing. The proper response is to turn the universities into custodial institutions, putting up the sign ‘Abandon home all ye who enter here’ and setting up halls of residence as an institutional chastity belt.

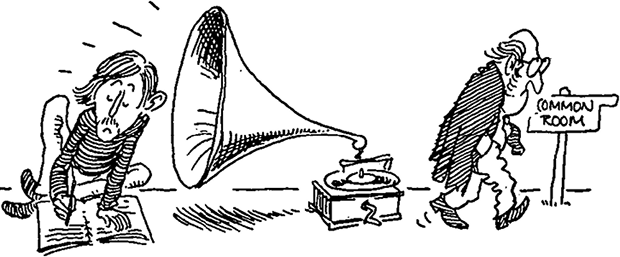

The staff are kept under control by the need to compete for scarce resources. Most departments are run on a slender secretarial staff, usually a brunette. They are understaffed and can’t finance research projects. Staff want new premises, sabbatical leave, or a trip to a conference in Australia. So all are controlled by the constant need to lobby, to propitiate and to please. University staff abandon ambitions of being good academics and concentrate on being petty lobbyists and empire builders. The best brains in the university are absorbed in a self-generating process of committee work, caucusing and canvassing. Having thus ensured a quiescent staff, Vice-Chancellors can get on with their real jobs: making speeches about the Muldoon threat to intellectual integrity, lobbying for appointment to the Broadcasting Corporation, deciding whether to refer the Capping Magazine to the Indecent Publications Tribunal, or applying for jobs overseas.

The universities should do four jobs. First, they need to expand and order the body of knowledge. They do this now, but achieve an output of only 0.8 articles per capita per year, and that mainly by taking overseas experiments and research and duplicating them in New Zealand. With a little more productivity and a bit more attention to New Zealand subjects, all would be well. Even the second job of communicating knowledge retail to the detainees is well enough done, though the aerosol approach is preferred to the hand polishing Oxford considers appropriate.

The third job is to turn out, not working models of professional men on to whom a little knowledge has been grafted without immediate rejection effects, but intellectuals, people whose thirst for knowledge is like an addiction. The universities don’t attempt this. The public image of students is of ignorant, drug crazed militants. In practice most are quietly conformist: in the years I was one of the trustees of the De Tocqueville Fund, to award an annual prize of $200 for the biggest insult to authority in any year, we never had one entrant, beyond a case of accidental pant wetting at a north Dunedin kindergarten. Students are drawn overwhelmingly from middle class backgrounds, with as few as a fifth from manual working homes, a proportion only double the contingent from overseas. Thus background insulates them from the infection of new ideas. Staff-student contact is minimal. Where it exists it is largely confined to the one department: in a survey only one in ten had had contact with staff from another department. Cross-sterilisation seems more appropriate than cross-fertilisation.

A last role—spreading knowledge out into the community—is scarcely attempted. Few are more academically snobbish and purist than the academically dull. Even the academic branch of show biz, so flourishing in Britain, does not exist. The University of Canterbury viewed my television appearances as if I was running a house of ill-fame on the side. New Zealand universities are inward-looking, preoccupied with themselves, isolated from a community which desperately needs the information, the ideas and the stimulus and diversity universities could provide. Unfortunately to do so might upset people.

Seriously though, these universities are the best in the world. Don’t ask the students, they’re biased. If you don’t believe me, ask the staff. You’ll find them either doing their gardens or Post Restante, c/o University of London.

FIFTH LETTER

THE KIWI SCIENCE OF POLITICS

THERE ARE SOME aspects of life in your new home I’ve hesitated to talk about. People who let their gardens get overgrown, Invercargill, bodily odours—all these had to be left until you are strong enough to bear the shock. So had politics.

In God-Zone you approach different topics with an adjustment of your volume control. With sport, shout; with sex, whisper; with politics, mutter. America’s silent majority is New Zealand’s muttering majority. If you’re afflicted by that rare perversion, a passion for politics, you’ll have to mutter more than a German with a severe Oedipus complex.

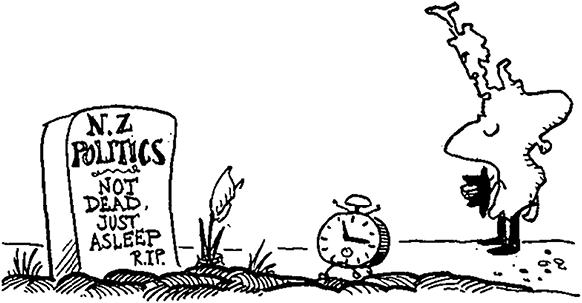

In the small amount of spare time they have left over from their main job of defending themselves against Mr Muldoon (the Genghis Khan of finance), the political scientists have been able to write numerous books and articles. By Mitchell’s Law, as the life goes out of politics it is replaced by analysis. This simple rule of taxidermy means that the duller politics become, the more frenzied and sophisticated is the attention that the burgeoning profession of political science devotes to the corpse. Voting turn-out down—analysis of elections up.

You will look in vain for the rapier shaft of wit which, in overseas systems, has produced such classics as ‘the thousand best jokes of Richard Nixon, the Abraham Lincoln of North Vietnam’, or ‘the wit of Edward Heath, the Bexley Bismarck’. You won’t find the sense of style which lyrical public relations men conferred on President Kennedy (‘with new DIGNITY!’) , or even the ersatz version the early Harold Wilson (‘You don’t use Wilson—Wilson uses you!’) had, until the aerosol ran out. True, Brian Talboys was run for a few months as an import substitute Jack Kennedy (it’s amazing what they can do with silicones), but he was too good-looking. Nor will you discover new philosophical insights. The Thoughts of Chairman Norm have not yet joined those other slim volumes, Italian War Heroes and Arab Victories, in published form. There’s no Watt on Political Theory, and Linear Demand Coefficients in Econometric Predictive Models by R. D. (The Turk) Muldoon and Naval Heroes from Drake to Me by Fraser Coleman have yet to hit the waiting world. The people have rugby for national catharsis, and assassination of politicians has never caught on here. Ignoring them is so much more effective.

Politics is best compared with the septic tank. Septic tanks have no tradition: they are plumbed in with the house. Septic tanks have no elegance and no wit, though you may get the occasional gurgle. You don’t talk much about septic tanks. They burble along nicely with a triennial overhaul. Yet they do serve a certain purpose.

Most countries have only one system of government. Just as a high standard of living gives New Zealand more consumer durables than other countries, so it gives more systems of government per capita. On the latest count, there are four, changed in regular rotation with the seasons, like vests.

In January there is neither system nor government. Everything must stop for the summer break. If, by some divine oversight, the second coming falls due at this time of year, a third and final appearance will certainly be necessary to transfer Kiwis to another (and possibly inferior) heaven. In January such a happening would be as little noticed as licensing laws on the West Coast in the old six o’clock closing days. You may find it surprising that revolutionaries don’t take the opportunity offered by this interregnum to take power and seize the reins. No real danger. Thoughtful immigration laws keep out people like Tariq Ali or Cohn-Bendit, excluding brown, pink and yellow with equal impartiality. And the local revolutionaries are all dinkum Kiwi. In January they’re on holiday, the one at Ninety Mile Beach, the other on his power boat at Taupo.

In February the country slips into its totalitarian phase, which lasts until May. Cabinet meets busily, its working hours coinciding neatly with the old pub opening times (which Orthodox boozers still keep, even if the Reformed Brethren don’t). To remain busy in the lunch break, the ministers put on morning suits, transforming themselves into the Executive Council, or Cabinet sitting pretty. On days Cabinet does not meet, ministers while away the time with tours of the country finding out what their departments are doing, or where they are. A minister’s ability is usually measured by his mileage.

These are the months of decision, when the beehive buzzes with activity. Import licensing is imposed or taken off. Subsidies are abolished. Controversial decisions are announced, usually on a Friday night so that newspapers, printed without journalists on Saturday and Sunday, can deal with them only when they’re dead issues. Troops are dispatched to wherever our allies (collectively known as the logic of destiny) would like them to go—usually Southeast Asia, an area the Kiwis are anxious to make safe for mutton. It’s moments like these we need SEATO.

All decisions are unchallenged. Parliament stands silent or is hired out to international organisations needing a veneer of respectability for their gatherings. The Opposition hibernates in some undiscovered retreat in the South Island. Both Parliament and the Opposition will discuss all in due course, but so late that the debate will have the compelling fascination of a postmortem on a body several months putrescent.

From May to December the nation takes on the trappings of Parliamentary Democracy. Stroll down to the House and along the corridors of power, with the rattling floorboards specially designed by the security service to give warning of arriving assassins. The Parliamentary traditions you will find are those of Burke and Hare rather than Burke and Fox. When interest was greater the country could support a double feature in the General Assembly (R.18) and the Legislative Council (R.75), a political geriatric ward. In a memorable debate this last chamber once debated a proposal to enhance the tourist attractions of Dunedin and give pleasure to the local Italian population (Sig. Giuseppe Martini, 1 Michie St, Roslyn) by buying a dozen gondolas to use on the harbour before it silted over. Ever conscious of the need for economy, always a pressing consideration with Otago estimates, one elderly councillor rose from his slumbers to move an amendment to buy not twelve gondolas but just a male and a female and let nature take its course.

The House is similar—witness this scintillating exchange between Sir Sidney Holland, believed to have been Prime Minister, and Mr Hackett, who may have been a spokesman of the New Zealand Federation of Hairdressers and Dental Surgeons:

Mr Holland said that the country was getting good value for the money spent on the police force. What other workers worked overtime without any special pay he asked?

Mr Hackett: Nurses in hospitals.

Mr Holland: They are not policemen. (Dominion 26 October 1956.)

Demosthenes would not have been allowed to enter New Zealand but his traditions are well maintained. Listen to this polished oratory from a former Minister, Mr W. J. Scott:

‘Part II of the proposed regulations deals with the operation of fish farms. Regulation 15 declares that a licensee of a fish farm may lawfully be in possession of or sell or dispose of fish he has raised on the farm, but subject to the provisions of the regulations. Regulation 16 provides that a licensee may have on his farm only fish which have been raised on the farm or lawfully transferred to the farm and that a transfer can take place only with the authority of the Secretary for Marine. Regulation 17 prohibits a licensee from canning fish or being in possession of fish in cans which have been raised on his farm.’ (Parliamentary Debates, 1 October 1969.)

Oratory is complemented by a deftness of repartee which would have gladdened the heart of Disraeli and his straight man, Gladstone:

Mr Walker: I am reminded of the occasion when he was most critical in this House about rates going up in Christchurch … on the night the rates were discussed by Christchurch City Council the honourable member had leave to go to the Labour Party Ball.

Hon. R. M. Macfarlane: I did not go to that ball.

Mr Walker: Well, the member was not at that meeting.

Mr Hunt: That is absolutely untrue and the member knows it.

Mr Holland: A point of order, Mr Speaker. I draw your attention to the fact that the member for New Lynn interjected saying that what the member said was perfectly untrue and the member knew it.

Mr Speaker: Is that what the member said?

Mr Hunt: Not exactly. I said it was absolutely untrue.

Mr Walker: Experience throughout the world has shown that properties adjacent to a motorway increase in price when the motorway is completed.

Hon. H. Watt: That is a lot of rubbish.

Mr Walker: Property adjacent to a motorway increases in value (interruption).

Mr Speaker: Order. We should not have more than ten people speaking at once.

Mr Walker: I should like to hear the Deputy Leader of the Opposition deny that.

Hon H. Watt: I deny it.

Mr Walker: I should like to hear him deny that Memorial Avenue in Christchurch ….

Hon. H. Watt: That is not a motorway.

Mr Walker: It is a mini-motorway.

Such is the lightning flash of free debate and the challenge of the interplay of ideas.

Though honest and far from glib, our politicians are not guileless, so use this parliamentary terms guide:

TERM: ‘I withdraw.’ TRANSLATION: ‘My allegations are almost certainly true and will stick anyway, now that I’ve made them publicly, but since the Speaker is one of their party hacks not ours, I’ll have to pretend to disavow them in order to get on to the more damning allegations of dishonesty and malpractice later on in my speech.’

TERM: ‘That’s not correct.’ TRANSLATION: ‘He’s right, but by the time they’ve checked, the whole business will be forgotten.’

TERM: ‘The minister is out of touch with his electorate.’ TRANSLATION: ‘My God he’s a good minister—there must be some way of getting at him.’

TERM: ‘I would require notice of that question.’ TRANSLATION: ‘I haven’t the foggiest idea.’

TERM: ‘The member is making debating points.’ TRANSLATION: ‘My God he’s right.’

TERM: ‘Ministers are constantly tripping round the world.’ TRANSLATION: ‘It’s now long enough for them to have forgotten how many we had.’

TERM: ‘A full and frank exchange of views with the American President.’ TRANSLATION: ‘I

got my orders.

TERM: ‘Making a political football out of a complex issue.’ TRANSLATION: ‘They’re on to a good thing.’

TERM: ‘The people will not fall prey to glittering bribes.’ TRANSLATION: ‘We’ve not got much of a policy this time.’

TERM: ‘I wouldn’t stoop to deal with such tawdry accusations.’ TRANSLATION: ‘I couldn’t.’

TERM: ‘I don’t want to use my full time.’ TRANSLATION: ‘I shall only want a short extension.’

TERM: ‘Despite their attempt to discover new policies the other side of the House haven’t changed basically.’ TRANSLATION: ‘How come we’ve nothing new to throw at them.’

TERM: ‘This is no time for defeatist talk.’ TRANSLATION: ‘We’ve got the country into a mess.’

TERM: ‘That question does not follow from the first.’ TRANSLATION: ‘Good heavens, they forgot to brief me on that.’

TERM: ‘I call on the Government to resign.’ TRANSLATION: ‘I’ve run out of ammunition.’

TERM: ‘The Opposition opposed the sale of state houses.’ TRANSLATION: ‘We’ve got to get them off the housing problem. They’ve got too strong a point.’

To change the subject from Parliament, as Mrs Kirk would say, we have a fourth stage of government, People’s Democracy, though we should perhaps omit ‘people’s’—it worries Brigadier Gilbert, even with the P.D.S.A. Every third year, in November, power passes to you personally, though you may have to share it with up to one and a half million others, depending on how many bother to vote. Only now will you realise the full promise of New Zealand politics for they have the most promising politicians in the world. There is no corruption: they aren’t the kind of politicians people would want to vote twice for. Besides, the New Zealander rarely puts cash down. Time payment is the system with politics as with cars. Win now, pay later.

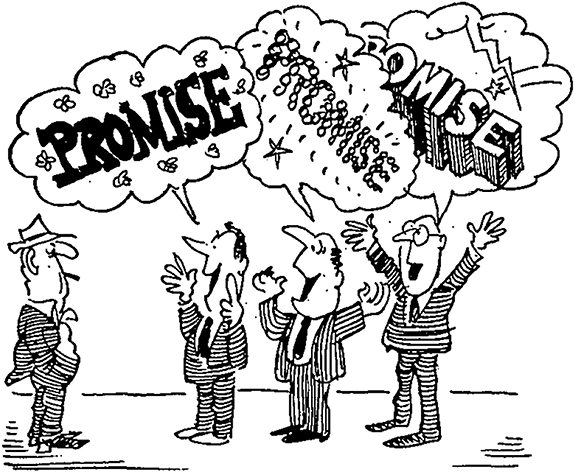

Elections have little to do with politics. They are the local variant of that vital Pacific religious phenomenon, the Cargo Cult. Only in New Zealand does it reach the full apogee of its development. The cargo promised is more lavish and, instead of one prophet to promise it, the Kiwi can choose between three. Ministers who have been arguing the need for discipline, effort and restraint will suddenly discover that things have never been better. The country is moving to a limitless future given the continuation of present policies. Even Mr Muldoon will hover, momentarily, on the brink of a smile as his eyes move away from the television interviewer to seek out the camera. The Opposition, after three years of complaining about current messes and looming difficulties, will find that with a little painless correction administered by them, all will be well. Social Credit prophets, always inclined to inflation, will outbid both the others.

The rites are the same as in any other Pacific Island. The cargo is the same: cars (you will begin to feel like buying one), houses, cheap credit. You name it and if it’s not against the moral code it’s coming. Even if it is, the politicians will hold out imprecise hopes of a change in the code. Unfortunately, the electors only half-believe the promises. The age of faith died with Michael Joseph Savage, a political Liberace of his time. Now politicians have to promise ever more strenuously so they can combat disbelief.

Elections have occurred so regularly for so long that they are now firmly implanted on the collective subconsciousness. Like Pavlov’s doggies, New Zealanders would still find themselves in orderly queues outside polling booths on the last Saturday in November every third year if Tom Pearce seized power and cancelled elections as a distraction from rugby. Kiwis abroad tramp alien streets looking for a polling booth because some deep tribal instinct stirs within them.

Kiwis vote for non-political reasons. Keep politics out of elections. Broadcasting has already gone too far by calling in professors of political science to comment on the inaction like a Greek chorus which has wandered into a low class burlesque house by mistake. The scientists hover over the electorate like the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, only more portentously—and mercifully more briefly. They then return to their studies to carry out a detailed analysis which fails to emerge before the next election. They should stick to games-theory analyses of the New Zealand Rugby Union. New Zealand elections are the province of professors of anthropology and religious studies. They at least are trained to understand tribal ceremonies.