Полная версия

The Pavlova Omnibus

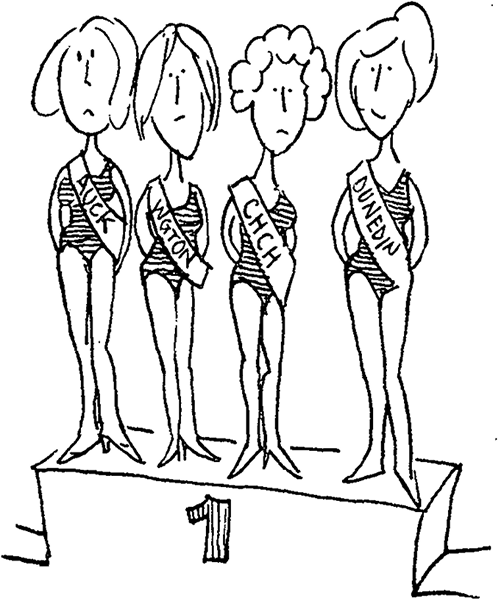

Size also means that Auckland is a self-sufficient universe, labouring under the delusion that the rest of New Zealand doesn’t exist and hence immersed in its own struggles and conflicts. Its academic squabbles are more bitter: anyone from the university can be kept going for hours just by mentioning his colleagues; a putting, in of pennies which produces a constant stream of denunciation. The city’s local government disputes are more intense. Its MPs hate each other too much to work together. Even the weather is undependable and extreme. One TV meteorologist had to move south because the weather didn’t agree with him.

Auckland is a collection of suburbs masquerading as a city. Wellington is a city centre without suburbs. They are all thoughtfully hidden away round in Rongotai, over the hills in Kelburn, or in the isolation ward of the Hutt Valley and its satellites such as Wainuiomata (or Nappy Valley as the locals have it). The suburbs are all several traffic jams away from the ultimate traffic jam in the centre. Wellington was designed as a capital city, but unfortunately its site wasn’t. The curving streets seem to mark the place the tide washed the surveyors’ pegs to. Even the Hutt Valley motorway can’t obviate the fact that if God had intended Wellington for traffic he would have put it in Petone. So the motorway simply speeds traffic more quickly to the central jam.

If the steep hills clustering round the harbour make Wellington a little inconvenient for all but Sherpas, they also make it beautiful. Man’s attempts to ruin the scene by building in the monolithic style of the Maginot Line have hardly spoiled a view which must make it the world’s most pleasant capital city. As a capital it has the institutions of government, administration and diplomacy all concentrated in the central area. Auckland has the pretension and the glory, Wellington the power. It lacks the colour, for Wellington is a public servants’ town, a place to which the able and ambitious in the service must ultimately go. This makes for guarded conversation after the Rabelaisian overtones of Auckland, drab dress, but a more vigorous cultural life and schools whose children have the highest average I.Q. outside Midwitch. The tone is lowered only by the unfortunate fact that for half of the year Parliament meets, M.Ps pour in every Tuesday, and with them the attendant circus of delegations, representations and the ritual passing of begging bowls.

Still Wellington should be a truly beautiful city, if they ever finish building it. There is always the danger of earthquake but probably this is a slightly less appalling threat than that posed by the Ministry of Works. In any case Wellington could quickly and easily be given complete protection against nuclear attack from the air. All they have to do is paint a huge arrow on the roof of the Vogel Building with the simple legend, ‘To Auckland’.

Further south, Christchurch, City of the Plain, though more perceptively described as the swamp city. Christchurch likes to think of itself as an English city. This is partly because of the gardens and the presence of the Avon meandering through in its half-hearted search for the sea. It is also because of institutions such as the Cathedral, the private schools, the Press and the Medbury Hamburger Bar. In fact its town plan of straight lines leading nowhere and its flat, drab appearance both combine to make it more like a wild west town built in stone. John Wayne would almost certainly have hired it as a set for his westerns had the municipality been able to devise some way of joining the parking meters together to form hitching rails.

Christchurch is really English only in its social segregation. The ability to sprawl in any direction has allowed segregation by suburb in a way that the hilly sites and the jostling mixtures of Wellington and Dunedin have not permitted. Professionals work in Hereford Street making fortunes and they live in Cashmere or Fendalton (where the camel hair coat went to die). The remaining suburbs are nicely graded. Any estate agent will guide you to the appropriate one once you’ve told how much you can afford to pay over what you can afford to pay. If he suggests Sydenham or New Brighton you should start thinking of a new job. The latter has a run-down atmosphere and gawping icecream-eating crowds doing their Saturday shopping. It also houses more cranks to the acre than any other part of the country.

With this social segregation, its insularity and introspection and the general stodginess of the little interlocking group who rule the city, Christchurch must be the least pleasant of the main centres. Yet I’m tolerant enough to believe that other people may think differently. Perhaps the real symbol of Christchurch is the railway station, pretentious and monolithic, yet with only about half a dozen trains a day that go anywhere beyond Christchurch suburbs, and only the Southerner that really goes at all. This train provides the best view of Christchurch.

Dunedin, the semi-sunkissed city, is symbolised by its long uncompleted Anglican cathedral: impressive in conception, solid in execution yet incomplete and left standing half finished for decades. The little town that Santa Claus forgot sits near the bottom of the South Island and of every growth table. Outwardly pretending that the wolf at the door is a lucky black cat it is really characterised by a militant inferiority complex. Or rather its official organs and leaders are. The mass of the population don’t care, finding it a pleasant place to live and so much less expensive than real life.

None of the conventional images of Dunedin are true. It is a university town only in the sense that the university bulks large in a city where it is the only expanding industry. The real relationship is symbolised by the moat round the Scottish Baronial Gothic. Scottishness means only that the import-restricted haggis puts in an occasional appearance and an occasional poet produces third-degree Burns. It is Presbyterian only in that the reverberating echoes of a small centre enforce conformity. Even so it manages an enviable reputation for provision of whatever favours sailors favour. It still gets more than its fair share of Truth reports, even since the demise of the Quarter Latin, Maclaggan Street. Psychologically and weatherwise Dunedin is a city of myths. Still it has more memories and fatter history books than anywhere else. These are some comfort to a city living in reduced circumstances with the feeling that life is passing it by.

By Seath’s Law, parochialism varies in inverse ratio to size. Auckland and Christchurch are big enough to be confident and know they’ll grow, whatever governments decide or pressure groups urge. Dunedin has to be more clamorous in the hope that hysteria will rectify the obstacles an inconsiderate nature has placed in the path of development.

The jostling second division of thirteen smaller centres ranging from Hamilton and Palmerston North down to Gisborne and Whangarei need to be more vocal still. Lacking main centre status they clamour for the outward and visible signs of city stature—a university, a new airport, a Government Life building, a railway, a piecart. Insecurity is heightened by the unconscious realisation that no matter how they grow they’re all irredeemably towns not cities. Links with hinterlands are stronger, urban identity weaker, life rawer and culture more consciously created. The intellectual élite of teachers, administrators and professional men are all consciously in exile, anxiously tilling the cultural desert around them. After-dinner speakers are hard to attract because it is customary to say something nice about the town they are speaking in. University staff are easier because they get mileage. In my days as an itinerant academic jukebox, visits to Invercargill, Nelson or Palmerston North gave me an insight into how St Augustine must have felt, so assiduously did the intellectuals present hang on to my words. Initially I put it down to the brilliance of the lecture. Later I realised that there wasn’t much else for the four of them to do.

Secondary centres are in the unhappy position of not being big enough to have the compensations of real cities, yet not being small enough to have the quiet contentment of the real focus of New Zealand life: the small towns. Through these runs the great dividing line between the urban and the rural. The smaller the place the greater the importance of rural values, the more local services depend on the farmer, and the more his income determines the cash flow into the community. The more, too, that rural values and attitudes predominate.

There are regional differences. There is the slowly awakening Northland; the declining glories of the West Coast where men are larger than life and twice as tipsy and the New Zealand myths crawl away to die. At the other extreme are the gentry pretensions of Hawke’s Bay and North Canterbury. Cow areas differ from sheep, not as Oliver Duff thought because sheep make gentlemen and cows unmake them, but because sheep make money, $1,000 per farmer more than cows. Cows not only provide lower average churnings, they also demand more attention from the ‘moaners on the mudflats’. The sheep farmer has more leisure, a different life style. Fruit and tobacco areas are different again: heavy demands for seasonal labour make Nelson and Hawke’s Bay agricultural factories at certain times of the year. Small holdings and subdivision make parts of the Maori east coast more of a rural slum.

Whatever the regional differences, the pattern of life is similar in all the small centres: intimate communities in which everyone knows everyone else and their business even better. They are warm and friendly, tolerant of human frailty (like the odd wife with a black eye, the occasional pregnant daughter), though prepared to talk about it endlessly afterwards. They are family communities, middle-aged in values and attitudes. The young move on for jobs and education. The outsider assumes there is nothing to do in these one-horse towns—in fact there is everything. Voluntary activity runs all, from church groups to those high points of the year, the races and the A. and P. shows. The farmers till the land, their wives cultivate the wilderness of leisure.

These small towns are the real New Zealand, nurturing the values of warmth and friendliness and an endless interest in personal trivia. They set the tone for the whole nation. The attitudes, perspectives, institutions are those of the small town writ large. Parliament is the small town forum, the national equivalent of pub exchanges. The friendly neighbourhood security service under Brigadier Keystone also plays an allotted role, although it couldn’t find a communist plot if it were stood on Lenin’s grave. Its number is in the phone book so that you can always ring up and turn in your friends for fun and profit. Like the village Nosy Parker its job is to gather information. It is an institutional Big Neighbour.

Even the New Zealander’s reaction to the nuisance of dissent is the same as the small town threatened with something out of the ordinary. The New Zealand Clobbering Machine is the national equivalent of small town community pressures. The things people are least happy about, political parties, class conflict, organised protest and dissent—these are just the things which don’t exist in the small town so the folk can neither understand nor accept them.

So think of New Zealand as a small town with the trimmings of a nation state. Seriously though, you must admit that this small town tone makes for a friendly personal atmosphere as distinct from the impersonal anonymity you’ve left behind. And if you don’t like it, keep quiet. You might be run out of town—on Air New Zealand.

FOURTH LETTER

EDUCATION: The Making of the Resident

AN OXFORD college head once assured me that all New Zealanders look alike: tall, craggy featured, nothing to say. If he was right it must be because they are produced by standdardised processes, one of the most uniform production systems in the world outside die stamping. And thorough. New Zealanders spend as much time and trouble on raising young New Zealanders as they do on sheep. They can’t spend as much money, but the people aren’t intended for export.

The family is the basic unit of production, but you have to make allowances for it. Rearing New Zealanders is too important to be left entirely to families, who could, after all, include English immigrants, Labour voters and undetected libertarians. So all the way up the line the product is processed in government plants during the day and shuttled back to the home storage units at night and weekends.

In the beginning is the hospital. Babies have to be born there so that regular feeding can programme them to wake Mum at regular intervals and she can be made to feel guilty about such anti-New Zealand habits as sleeping after six a.m. or getting too much pleasure out of a child. Dad’s exclusion from the process of birth and his grudging admission to the hospital conditions him to the view that the whole business has nothing to do with him. His job is restricted to waving rattles before unseeing eyes and going ‘Goo-goo’. Neither his role nor his ability to communicate with his children ever improves much.

After hospital the Plunket Society, a paediatric Farm Advisory Service, steps in to reinforce the lessons. Its purpose is to check the spread of permissiveness and plastic pants among children under one by propagating the principles of child rearing common in advanced circles only fifty years ago. These rules were set out by Dr Truby King in his book Scouting For Mothers. Children should be a duty not a pleasure. Mum must not be allowed to bring up children in the way she wants. Parents should be seen and not heard.

Orwell’s 1984 had a television camera in every room. New Zealand uses an inspectorate of Plunket ladies observing home practices, administering gentle correction where necessary. They are kinder to the children than to mothers. Plunket reports will surely be weighed in the scales of heaven, so they must be charitable. One day my daughter screamed continuously, bit the nurse and deposited what should have gone into the nappy in her lap. The record card commented mildly, ‘An independent wee soul’.

A former Governor-General pointed out that ‘if it were not for the success of the Plunket Society there might be no All Blacks’. There would be no Progressive Youth Movement either. The society makes New Zealanders what they are. It begins the lifelong tension between what we want to do and what we are conditioned to feel we should do. Young Everidge wants to eat when he’s hungry; he’s conditioned to nibble at four-hour intervals. He wants to play with himself; his hand gets slapped to show him sex is a dirty pleasure, suitable only for the dark. As a former Obergruppenführer of the Plunket Society once said, ‘Give me the child for seven months, with whatever donations you can afford, and I will give you the All Black.’

In case conditioning fades, there is an after-sales service from 250 kindergartens and 300 play groups. These socialise the children to play together, but only incidentally. The main purpose is to give the mums something to do. These places are an outlet for that frenzied organisational drive which is the first symptom of postpuerperal depression, a chance to trade in old gossip for new and an opportunity to keep a wary eye on everyone else’s child-rearing procedures. Is Sandra Binns’s toilet training late? Her mum will be made to feel anxious. Does Johnny Jones go in for full frontal nudity? After all, the children won’t be really happy unless they’re exactly like everyone else.

This is also the view of the Department of Education, the intellectual branch of Sir James Wattie and company. Overseas they think of education as a process, a liberation, a joyous awakening. Such emancipation hardly fits in with the New Zealand skill of regulation. It would produce a storm of protest from parents puzzled that their children should reject a life style they themselves have known from time immemorial (i.e. 1935). So this country has changed the meaning of the word. Education means a department, seeing that all plants produce to the same standard, turning a process of emancipation into a means of integration. So no one wants any.

The basic function of any government department is to keep its field of operations quiet. Education clings to this rule all the more anxiously, since its one aberration revealed the dangers of an alternative course. In 1935 Labour appointed a Minister of Education who was interested in the subject, had ideas and could push them through Cabinet—all factors which would have disqualified him for the job in normal circumstances. Peter Fraser and Dr Beeby initiated a primary school revolution. The authoritarian ethos was weakened. The insistence on the three Rs of reading, riting and rigidity was replaced by an effort to capitalise on the child’s instinct to learn. Dr Dewey came to New Zealand to be embalmed in state.

The effort was too much. The revolution exhausted itself on the primary schools before it could reach the rigidly conservative postprimary schools. Now, a slightly archaic and staid liberalism of the primary system sits in schizophrenic contrast with a postprimary system, where instruction is handed down to be duly carved on tablets of stone.

The backlog of hostility from an older generation which had not enjoyed its own schooling and was determined that no one else should, made further innovations impossible. The collapse of morals, the untidiness of state house gardens and the growing incidence of public nose-picking were all authoritatively attributed to ‘play-way’. Dr Bee by was sent off to be New Zealand ambassador to the Folies Bergère. The Department confined itself to administration. Since it is now largely manned by ex-teachers, the present system is safe and self-perpetuating. Those who can, teach; those who can’t, administer. Those who can do neither become ministers.

As a final safeguard, education is administered by a complex balance of groups, so nicely deadlocked as to make change impossible. Boards are in friction with the Department, headmasters with boards, staffs with all three, school committees and PTAs with any two at random. At the top of this house of cards sits the Minister, whose main qualifications are usually his complete inability to get anything through Cabinet and his enthusiasm for those educational techniques common in the late nineteenth century. In this way everyone in education can be left to fight everyone else so that the rest of the population can spend their money on booze, baccy and betting and the Government can go out shopping for frigates.

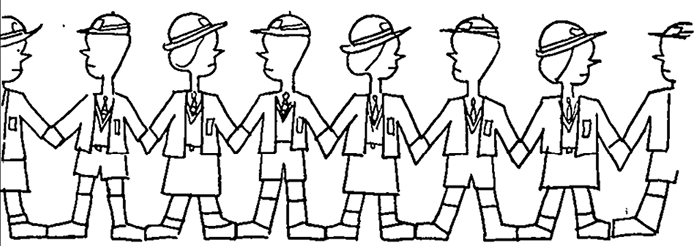

From the primary plant, young Kiwi-chile passes on to the intermediate school to reach puberty in decent purdah. He then enters a postprimary system divided into three parts—Catholic, Private or State. Catholic schools segregate the members of the faith and provide an inferior education suited to a minority of a seventh of the population. Private schools (the National Party at lessons) do much the same for the better-off. Most pay a nominal allegiance to a religious denomination and a more real one to the eternal values represented by the ANZ Bank. They are preparatory departments for Federated Farmers, providing boarding accommodation and reasonable restraint for country children. The more important, Christ’s, King’s and Wanganui Collegiate, are instant public schools, die-stamping little Englishmen under licence. Their female counterparts also produce some splendid chaps.

The more pretentious take English or religious names: St Margaret’s after the wife of the founder of F. W. Woolworth, Christ’s after the founder of the Church of England, Medbury Preparatory after the inventor of the hamburger. Most were founded in the mists of antiquity, like Southwell, starting in 1911 on endowment from the Sergei family, which still provides donations in the shape of a headmaster and children. Educational techniques which trained administrators for the British Empire and other Offshore Funds are applied by hand to a miscellaneous collection of offspring of farmers, lawyers and used-car salesmen (the country’s second oldest profession). This gives the well-off something to spend their money on besides overseas trips. It also guarantees that their offspring won’t be embarrassed by coeducation. All relatively harmless, since New Zealand is not an élitist society. The private schools can’t yet take in ESN children of the wealthy at one end and churn out directors for ICI (NZ) at the other.

Because the private schools use their privacy to uphold a traditional education, the state schools have to do the same so parents won’t divert their children en masse. As a new country, New Zealand is a great respecter of tradition and the schools which carry the most prestige are the most rigidly pedagogic. Places like Wellington Girls, Christchurch Boys and Waikukumukau Hermaphrodites set the tone. All the others have to try to keep back with them, so that parents don’t think their children are being deprived.

By and large, which most of our children are, Joe Soap and Julian Unilever go to the same school. This is so that they can both start with equal disadvantages in life. For the army the schools are an excellent preparation. For life, not so good. New Zealanders are a lackadaisical, easygoing people: they educate their children by formalised pedagogy. Their dress is sloppy and casual: they impose a school uniform designed to kill all sexual interest by skilfully relandscaping burgeoning teenage shapes into mobile marquees. An open, democratic society, New Zealand has an authoritarian education system. The teacher is society’s NCO, enforcing the virtues of obedience by corporal punishment or accrediting. Society is egalitarian, so the schools stream rigidly. Kiwis are a practical bunch of jokers, so the schools are obsessively academic. All this has been carefully thought out to nurture the latent schizophrenia in the Kiwi breast, programming him to feel guilty and uneasy about everything that is good. Puritan instinct demands that those who live in paradise should not enjoy it.

The doses of guilt aren’t equally shared out. Manual workers and the less intelligent build up antibodies to the system. It conditions them to a cynicism about an education so uniquely irrelevant to their life experience and about authority figures who transmit on such an alien frequency. They leave school at the earliest possible opportunity and make money on the wharves, or rather less as Prime Minister or Leader of the Opposition. For the rest of their lives they are defiantly anti-intellectual. With the middle classes, the education system has deeper penetration, processing them into Boy Scouts who spend the rest of their lives looking for a movement, in such substitutes as Lions or Jaycees. Unfitted to enjoy paradise, they become deeply suspicious of those who do. The worst affected cases go on to the teachers’ colleges, the technical institutes and the universities for a really concentrated dose of educational schizophrenia.

When you think of further education, the red brick, the white tile, or the Dulux ivory towers of Britain’s universities spring to mind. Forget it. New Zealand has 4.3 universities and a number of training colleges and technical institutes which between them take, say, ten per cent of school leavers. They are all finishing schools for various professions, a job training for those who can’t get it on the job. The lower grades—primary school teachers and lesser breeds without the law—go to the educational ghettos. The rest go to the universities, and the difference between the institutions is solely one of degree. The universities embrace not only Classics (production quota as set by the Development Conference, 34.5 a year) but also Physical Education and the Home Science School (the Dean of the Home Science School is the equivalent of your Warden of All Souls; the school’s main role at the moment is to ensure that doctors’ wives can cook). Flower arrangement would also be eligible for a degree course if the Women’s Division didn’t already do it so well. Being a practical people, the New Zealanders don’t like to train intelligence at large; they have no tradition of taking philosophy graduates and putting them in charge of the Department of Marine, or appointing experts in the romance languages to run New Zealand Breweries. Studies have to be relevant to a career. Like freezing works, universities must produce visible returns in an annual crop of frozen teachers, accountants and engineers.