Полная версия

The Pavlova Omnibus

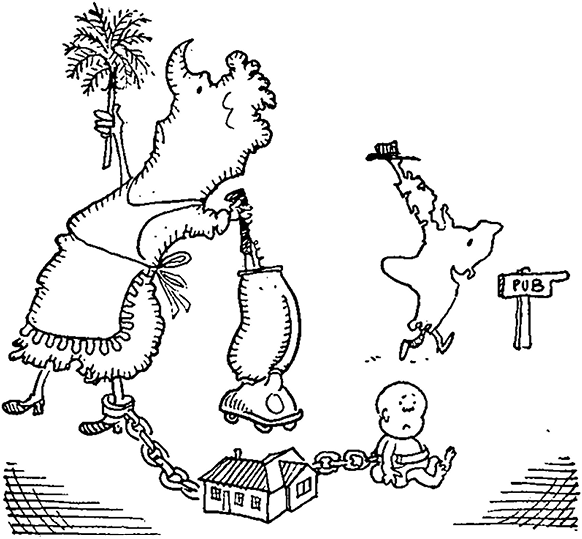

Unfortunately her role doesn’t provide universal satisfaction. Since she marries at 20 and has produced 2.6 children by the time she’s 28, the joys of being a homemaker (notice the distinction from the English ‘housewife’) can pall when the children grow up, if only because it’s useless. Sometimes she takes refuge in neurotic symptoms from backache to the National Council of Women. Or she throws herself into a strident hostility to change because she feels herself let down and without realising why, dimly puts it down to forces beyond her control. More than one in three go back to work around forty as an under-paid labour force, though slightly less exploited than the remainder, who devote themselves to the frenzied organisational work which alone keeps the machinery of welfare and education going. Committees are the opium of the people. The field of endeavour ranges from the Women’s Division to the Mothers’ Union competition for the best pikelet. Rarely does the embattled female fighting the rearguard action of life on one or all of these fronts realise that she is doing all this because the role she is programmed for has let her down.

Compared with the dogged singlemindedness of the single ladybird, and the implacability of the Great New Zealand Mum, the man’s role is that of an ephemeral faineant. While she bottles, he gets pickled, seeking escape from a home he can’t dominate, in the boozy camaraderie of the pub or the solitudes of the garden. The only thing he’s allowed to run is the car. He hasn’t even got the initiative to form the Men’s Liberation Front, the Y Front, to support his case.

While other advanced countries move towards unisex, this role tension between men and women is a basic division in their society. In literature it becomes a dominant theme of intermittent guerilla war or entrenched mutual incomprehension. In life it is the weak spot of their paradise, a vague, little understood dissatisfaction, a weakness in the roles they think should satisfy and fulfil, but somehow don’t. In other countries the social battleground reflects the basic tension in society: in Britain, class; in America, colour. In New Zealand the battlefield is sex.

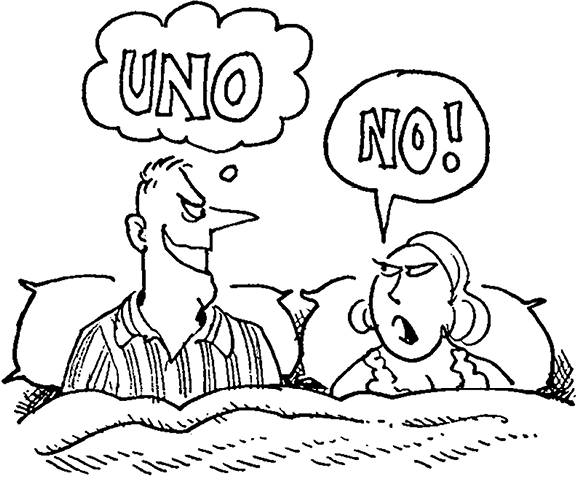

Your first impression will be that sex does not exist. The word is not used and the act itself is referred to as UNO, as in the phrase, ‘They were going out with each other for six months and (pause) you know’. UNO is thus different from ‘yer know’, because the one is something too shocking to talk about, the other too boring to discuss. Yet even when you know the name it is difficult to discover whether UNO exists. It may have been abolished as a distraction from the war effort by a government committed to the socialisation of the means of reproduction, distribution and exchange.

Where America goes topless, New Zealand has pioneered topdressing. The porn laws protect New Zealanders against the imminent threat of invasion from Denmark. No electrodeloaded volunteers devote themselves to a labour of love in the back seat of a mock-up car in some Auckland University laboratory and Patterns of Sexuality in a Northland Town by those well known social eroticians and bicycle menders Fischbein and Roganblatt remains unwritten. In Britain, women’s magazines devote themselves to the sexual problems of their readers: the formula for a successful newspaper’s women’s page is ritual doses of abortion, illegitimacy, divorce and the pill. New Zealand counterparts tackle more fundamental problems: ‘What to do about my winter sweet shrub which is making no growth, while the leaves have become brown, P.F. Auckland’. The Havelock you will hear about is North not Ellis and it is not necessary to get New Zealand Wildlife under plain cover.

Compared with Britain, this looks to be a cautiously antiseptic society. Prostitutes are as common as coelacanths and in most places taxi drivers will ask you where they can get a woman. Nary a nipple will confront you from the newspapers. Two-thirds of the population has fluoride in its water (the rest oppose it nail if not tooth) and you may well conclude that fluoridation eliminated nipples with dental caries. The idea of key parties where wives are swapped by the throwing in of car keys is unthinkable in a society more likely to throw in wives and swap precious cars.

Then you will begin to notice symptoms of UNO. In pub and rugby club, beer inflates the imagination, if not the libido. Men are men and women grateful for it—often. The Homeric narrators become the Edmund Hillarys of sexology; life a kind of sexual Outward Bound course. No scientific accuracy exists because Kelburn harbours no Kinsey defining norms for Ngaio or frequencies for Feilding. Yet feats are recounted in action replays, feats which would have tested the stamina of a sex-crazed superman, raised on vitamin E in Nero’s Rome. The narrators may exaggerate slightly in their surveys of the performing arts, but at least they think about sex.

Then you notice another symptom: the titivation industry. Much of this is imported. They don’t assemble pornography locally under licentiousness and the Feltex version of The Carpetbaggers has yet to be filmed, so the pornshop is not the grossest part of the G.N.P. as in Scandinavia. Nevertheless, the sex substitutes are there. Look at the movie billings. One newspaper described Irma La Douce as ‘a story of passion, bloodshed, desire and death—in fact everything that makes life worth living’. Others follow on similar lines. ‘Insatiably, music drove her onward’—The Sound of Music. ‘Shocking things, things that astonished the world, happened in this car’—Chitty, Chitty, Bang, Bang. Truth titivates. Its billboards are usually more exciting than the actual newspaper, but its headlines also excite. ‘Bedding-out in the North Island’—gardening column. ‘The Master and the Forty Boys’—overcrowding in primary schools. Here is a nation sublimating.

Stage three of the process of adjustment is the assumption that beneath the surface New Zealand throbs with a sexual activity from which you alone are excluded. You see few outward symptoms simply because sex is the most asexual activity. Everyone is sexually content, possibly exhausted. The prostitute has vanished because no one needs her. You alone are not getting your share and you begin to feel like the psychiatrist who wanted to be a sex maniac but failed the practicals.

Understanding comes as a compromise between these extreme views of bromideland or wall to wall sex. As in everything else, they conform to a norm: a quarter-acre, one-car, three-children, two-orgasm family. UNO exists. Unfortunately it can’t be talked about. This is partly because of their puritan legacy which makes it easier to get sex than actually discuss it. The small town environment, when Big Neighbour tenderly watches over them every step every yard of the way, also makes frankness difficult. Note that in Britain, adverts for feminine deodorants are quite explicit on where and why they are to be applied. Counterpart adverts in New Zealand could be for catarrh.

UNO involves relationships between people, deep feelings and emotions, things the New Zealander has been conditioned to avoid and repress. It brings up basic problems of the relationship between the sexes, that fault line in the New Zealand society. In America the social battleground is the streets—in New Zealand it is the bedroom. Here the role conflicts and tensions which characterise this society are put to the basic test. The battle goes on in an atmosphere of sullen incomprehension. They don’t know what it’s all about.

Hence the embarrassed silence: the altar of hymen has to be discreetly draped in candlewick. Children have to be left to find out for themselves which, being good Kiwi pragmatists, they promptly do. This is perfectly acceptable. UNO itself isn’t objected to—just indications that it goes on. A deaf ear is turned to anything that goes bump in the night, but one mistake brings the shotguns out and makes the erring youngsters sooner wed than dead.

If anything becomes public, the government will appoint a Royal Commission or the Railways Department will inquire into the Bluff-Invercargill train. This is the morality of ‘thou shalt not be known to’ rather than ‘thou shalt not’. Negative all this may be, but it’s vigorous. Since it can’t stop intercourse, it will stamp out contraception. It can’t check conception, so it will prohibit abortion. Critics who attack such acts as making bed situations worse, completely mistake the importance of morality, which isn’t really about other people but about salving our own consciences. The job of the moralist is really to push the inconsiderate tip of the iceberg (the point at issue) back under the water.

Formal instruction is ruled out, by their religious belief in the trinity of monkeys, so the great amateur tradition takes over. After a collective initiation in the group gropes, which pass for teenage parties, the explorers are off on their own (‘together we found out’). Their endeavours are confined to cars, fields and livingroom floors, so as to reinforce the inbuilt feeling that sex is dirty and beastly, and to preserve the feeling that marriage and clean sheets are a desirable goal. New Zealanders are among the highest users of the pill in the world (indeed thanks to it there will be over a quarter of a million fewer New Zealanders by 1990 than there would otherwise have been). Yet it is officially denied to the unmarried, which explains why the number of babies born in the first seven months after marriage now runs at around a third of nuptial first births and why the illegitimacy rate is second only to Sweden and has been rising more rapidly than practically any country, even without encouragement from the Monetary and Economic Council. Progressive churchmen have long been considering changing the marriage service to read, ‘I did’. Small wonder that in 1969 the government ‘authorised further research into the causes of the increase in extramarital intercourse’, a study which would have been as enjoyable as it was pointless.

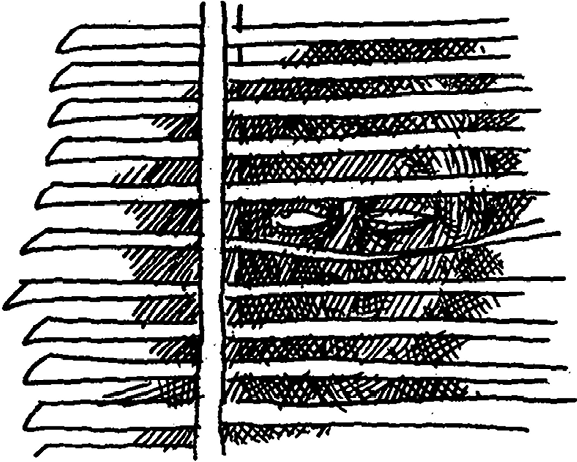

So there’s your final picture. New Zealand is a society in which sex undoubtedly exists—in fact it’s almost as common as rugby and can produce just as many injuries. Yet like rugby, it has to be restricted to amateurs. There is no pulsating promiscuity, just a rather sad amateur experimentation, a low standard of loving. In a drugged sleep, William James once thought he had stumbled on the key to the human dilemma. Hastily he wrote it down. He awoke next morning to read the legend, ‘Higamus hogamus, woman is monogamous. Hogamus, higamus, man is polygamous’. His disappointment was not at the triteness of the message but because it did not really apply to New Zealand. Big Neighbour behind the Venetian blinds does not allow the male Kiwi to be anything more than monogamous. His fierce female mate is determined to be nothing else. The unmarried experimenters enjoy a monogamy before marriage that’s almost as glum as the monogamy after marriage; by the time they are married they have lost the taste for the whole business.

In America they escape from monogamy by adultery; in New Zealand they escape by segregation, hence their parties. These typically fall into two camps: an unbeleaguered garrison of women and the men clustering in the kitchen to keep supply lines short. This enables men to talk about ephemera like sport, cars and sex and women to talk about homes and children. Their concerns are always the more basic and practical.

The New Zealand marriage is the transfer of the embattled sexual relationship from car seat to candlewick. The system isn’t likely to change. Co-education doesn’t undermine the set-up for it makes the Purdah Principle informal rather than formal. Even emancipation will work against women unless it is total and complete. For a woman going out to work means letting go of the tiller and surrendering real power for a dull job and a low wage. Even the extra income only boosts the man’s spending power since the Kiwi-hen is constitutionally incapable of spending money.

As for UNO it can only flourish when removed from the battleground and Big Neighbour. Visiting sailors, pop groups and American forces in war and what passes for peace are all outside the integration machinery so they find our sex life like our welfare state: rough and ready but free.

Still, I don’t want to seem too critical. The New Zealand woman is the most attractive in the world. She’s the best housekeeper and she brings up the cleanest children in conditions so antiseptic Dr Barnard would be proud to operate in them. She may prefer Alison Holst style to Graham Kerr but her cooking is certain to win your heart. It was after all Dr Barnard who remarked that the best way to a man’s heart is through his stomach. And even if she weren’t quite as good as I’m painting her I’d never dare tell you. She might break my arm.

SEVENTH LETTER

SEVEN DAYS SHALT THOU LABOUR: The Games Kiwis Play

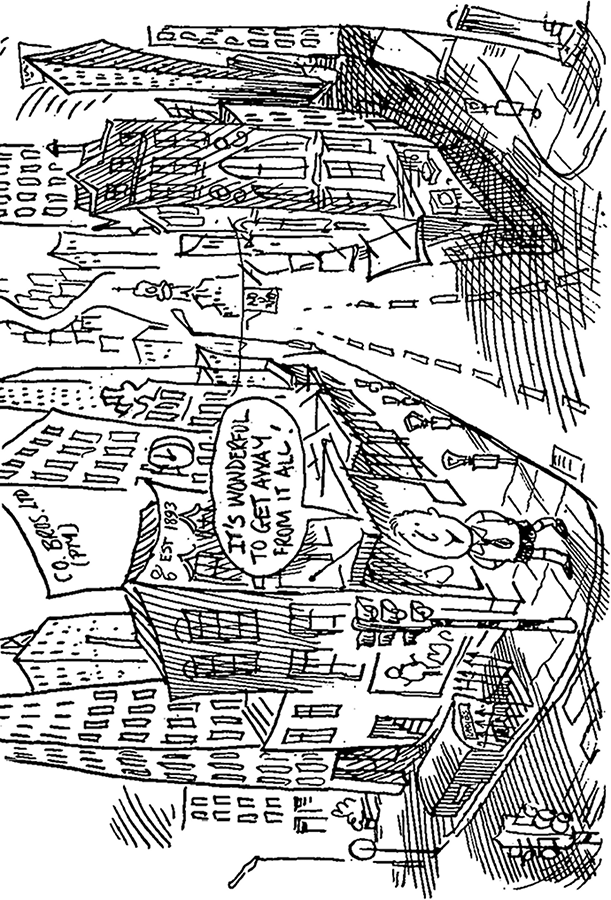

NEW ZEALAND is a land without leisure. What you call leisure time, Kiwis know as a period of maximum exertion. Outside working hours this is an ant hill (as distinct from Cashmere, the aunt hill) of effort. Inside working hours they recover. Maximum ingenuity has to be exercised in spreading out formal ‘work’ and reducing its strain to conserve energy for the ordeal ahead. The moralist may complain about lazy and slipshod workers. No one heeds him. The forty-hour week is a necessary recovery period for the other 128. Unlike the Germans and Japanese, New Zealanders have a sense of priorities. If they work hard it must be for themselves.

Leisure is so exhausting because there is nothing to do. Other countries have leisure and entertainment industries. Bowling alleys, drive-in brothels, theatres, clubs and other institutions cater for every taste from blackcurrant cordial to geisha. Everything is done for them, so the workers can gallop back to their factories relaxed, refreshed and entertained.

In New Zealand it’s different. Show biz hardly exists outside of a few itinerant pop groups, the Rev. Bob Lowe and that popular group, Dr Geering and the Presbyterian General Assembly. Visits from overseas artists like LBJ are few and expensive. By the time they get there they’re not at their best after an exhausting trip. Lord Reith, a titled undertaker who believed that television was a branch of the embalming industry, still wanders NZBC corridors, giving people what is good for them rather than what they want. As for night life, cities, while beautifully planned, are so well laid out that you wonder how long they’ve been dead. A search for the liveliest spot in town usually ends up at the YMCA As for discotheques, in the world of the with-it they stand without, though a few daring entrepreneurs have converted their milkbars into psychodelicatessens. Ten o’clock closing has hardly made the pubs social centres; in mixed bars you have to ask for an estimate before you drink.

Restaurants are poor by overseas standards. When Graham Kerr talked of ‘New Zealand, Land of Food’, pies may have entered his mind but he was probably thinking of sandwiches. This is their basic food as well as the foundation of their way of life. Before the sandwich all men are equal. It sustains more people more cheaply to the ton than any known nutrient, even Asia’s rice. It allows Kiwis to spend their money on essentials—such as cars and slimming cures. Schoolgirls stoke up on it into unlovely monsters beyond the help of power net Lycra or Maiden form bra. The menfolk are de-energised by the cloying pap. Citizens only eat out when they’ve got sandwiches. Otherwise it’s too expensive. With a night out costing as much as a gnome for the garden there’s really no choice. After a day of indigestion the meal is forgotten. A gnome is forever.

The Kiwis entertain themselves. Leisure begins at home. In the day they entertain there with coffee, at night with beer, and if the furniture needs renewing they give a party, pronounced with a ‘d’ to distinguish it from the less important political version. Whatever the social class of the host, parties are all eatathons and drinkathons. If it’s a student do, keep your half-G up your jumper. If everyone is wearing suits it might be a mistake to paw your host’s wife too soon. If it’s your party insure against damage, though remember third party rates are high. Attempting to ingratiate myself with my students, I gave occasional parties while my house lasted. At the penultimate party the bed legs were broken off by the weight of couples dancing on it (this was, after all, New Zealand). At my final party, a fellow lecturer was pushed through the livingroom window and a gatecrasher locked himself in the lavatory for four hours, with disastrous consequences for the lawn.

If you are at a loose end ring a taxi firm and ask them to drive you where the action’s thickest. Or follow people home from the pub and sidle in with them. Or join the other cars prowling the streets looking for signs of life. You won’t be welcome but it would infringe traditional hospitality rituals to throw you out before you actually collapse vomiting on the carpet. After all, the party is the great Kiwi contribution to social betterment. One of the great literary classics is called Government By Party.

The home is the focus of the nation’s life. Other countries go out for entertainment—Englishmen to sit in pubs, Ulstermen to murder each other in the streets. Kiwi homes are so much bigger, better and more beautiful, veritable people’s palaces, that the occupants don’t want to leave. The homes are also so expensive they can’t afford to. The home is the venue for their most popular forms of entertainment: television, gardening and peering out of the window. It’s also a hobby you inhabit, and so exhausting that no New Zealander ever calls his house ‘Mon Repos’.

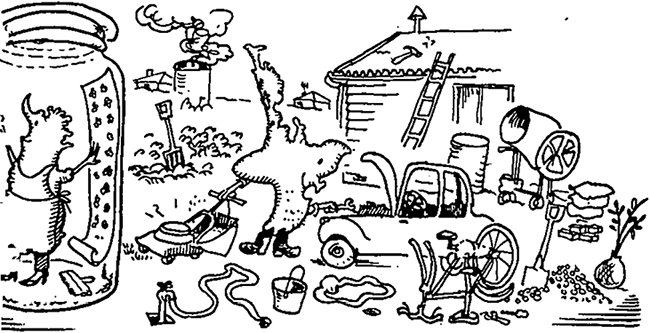

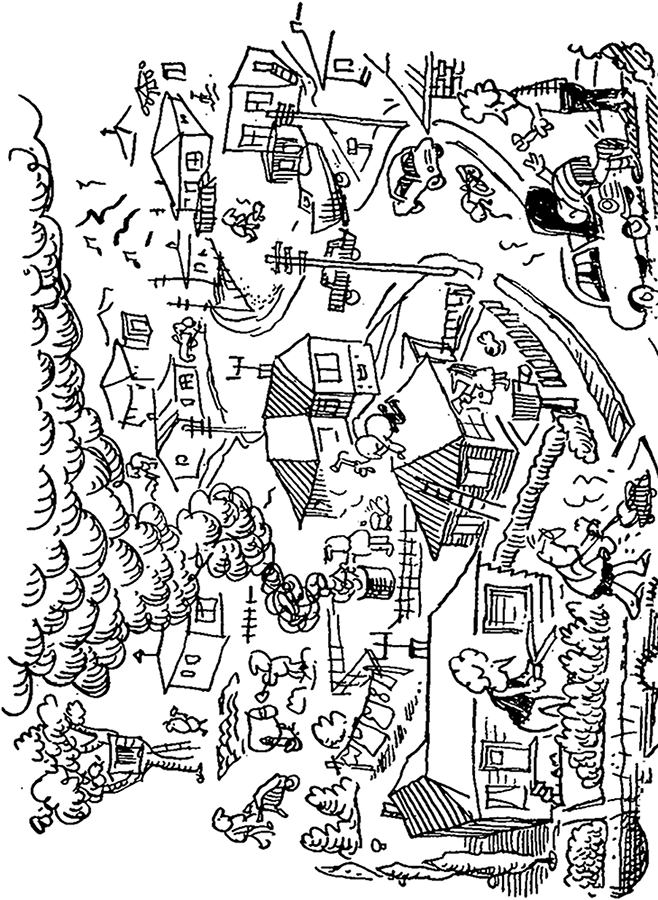

Americans flee the noisy cities to the quiet of suburbia. If you want weekend peace you must go to town. The suburbs are a cacophony of power drills, motor mowers, hammers, carpet and child beating and revving cars, all punctuated by the screams of amateur roof menders falling to their deaths. A New Zealand house begins life as a 1,000-square-foot wood or brick box, sitting in a sea of mud and rubble rather like Passchendaele. Within months the garden is a condensed and improved version of Versailles, likely to turn Capability Brown green with envy. Hand-manicured lawns get more care and attention than the owner’s hair. Vegetable gardens carry a crop large enough to feed the entire Vietcong for decades.

The house’s turn comes next. First a decoration, then an extension and enlargement, then an extension and enlargement to the extensions and enlargements. Once the major work is done, maintenance, redecoration and the addition of the occasional bedroom or ballroom keep things going until it’s time to move on and begin over again. The Englishman’s home is his castle. It’s the New Zealander’s mistress.

All this he does himself. In countries where work is highly specialised, do-it-yourself is a kind of escape from specialisation of labour, a return to craftsman traditions. The man who spends his life on a car conveyor belt tightening, or in Britain half-tightening, the fourth fender junction bolt can recapture the joy of being a jack of all trades. In New Zealand work isn’t specialised. The only division of labour is the relationship between Tom Skinner and Norman Kirk. It is a nation of all-rounders who have to repair cars, build houses or decorate them because no one else will do it for them. Break down by the roadside and any passing driver can repair your car; one astute Englishman took a wreck from the scrapyard, dumped it by a country road, and by the time the twentieth passing driver had contributed his skills he had a machine capable of 0-60 in 10 seconds and 58.5 mpg

I still remember the hysterical laughter on the other end of the line when I rang a Dunedin plumber to ask him to put a washer on the tap. My inability at gardening was a short-lived joke until the landlord realised that the psychosis was incurable. Then it became a subject for hostile comments and surreptitious dawn visits to do the garden with muffled mower while I slept. I was lucky. One friend allowed his garden to get into such a state of neglect that the neighbours reported him to the Health Department, presumably after finding the Security Service reluctant to intervene. No official inspection machinery is necessary when Big Neighbour watches, and most New Zealanders spend Sunday afternoons driving round the suburbs inspecting everyone else’s homes and gardens. The law intervenes but rarely, as when Otago University students started an epidemic of gnome stealing and butterfly daubing. This ended only when Mrs McMillan threatened to reintroduce the death penalty.

The home is a basic unit of production for children and goods. Other countries have mass production and conveyor belts. New Zealand needs cottage industry because it is less efficient. For the men the home is a garage and service station. The car isn’t a consumer durable but a shrine, as well as being one of the few means of population control not proscribed by the Pope. For it kills over six hundred people a year. There is one car to three people because home garages keep on the road cars which would elsewhere appear only for veterans’ rallies. It is a bit early to tell, but New Zealand may have discovered the secret of perpetual motion. The glory that was grease.

The home is also a market garden. And a brewery. The massive hoardings which proclaim ‘Dominion Bitter’ aren’t to encourage you to drink this brew, but to express the feelings of the directors about their untaxed competitors.

The female production staff devote themselves to making jam, clothes, cakes and scones on a massive scale. The fruit is better preserved than the women. In the preserving season places where teenagers meet are suddenly all male—the girls are bottling. ‘She’s a bottler’ is the highest praise a man can give about a woman. Yet female ingenuity extends in all directions. The Woman’s Weekly regularly offers thousands of ideas for economy, ranging from making candlesticks out of bobbins to interuterine devices out of short ends of fencing wire. Indeed its surprising that dustbin men have to call at most New Zealand homes. Continuous recreation of matter was invented here.

This massive cottage industry allows the people to afford all the consumer durables they couldn’t buy if they had to spend money on clothes, vegetables or jam. Unfortunately it also makes these things inordinately expensive for the less dextrous.