Полная версия

The Pavlova Omnibus

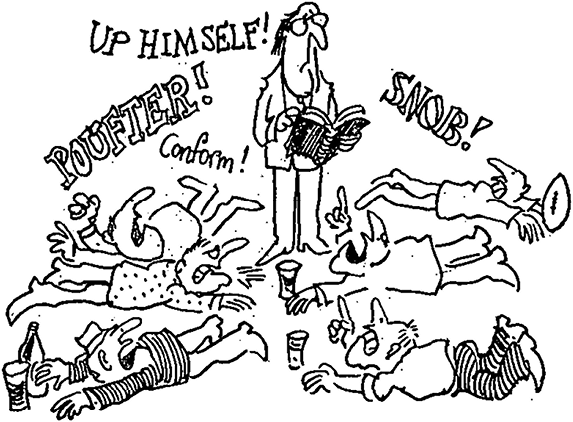

Kirk’s Law of Social Gravity states that the higher you go the more they will try to pull you down. If you are in an élite position you must disguise the fact in two ways. The first is to look as vacuous, illiterate and normal as the rest of the populace. A startled British High Commissioner once observed Sir Keith Holyoake ‘declaring with pride that he was no intellectual, he was not well educated, he had left school when he was fourteen and had never been near a university’. The High Commissioner, of course, failed to realise that all this made Sir Keith peculiarly well fitted to be Prime Minister, just as a familiar array of qualifications admirably fits Mr Kirk for the same job. No New Zealand Prime Minister this century (with two exceptions) has been near a university, unless to slip in by the back door to collect an honorary degree under plain cover. Few politicians have verged on the literary. There is no tradition of political alibiography; few even dare to leave letters for a historian to do his job of transferring bones from one graveyard to another. The second disguise is to eschew the prerogatives of office. Ministers’ rooms must be open to every passing lunatic. Even the Prime Minister can’t afford to ignore the Tapanui Women’s Division. Peter Fraser used to show that running the war effort wasn’t making him big-headed by popping out to inspect leaky roofs on state houses. Keith Holyoake was ever ready to find suitcases lost by indignant railway travellers. When I told this story to a French television crew they incredulously tested it by ringing the Prime Minister from their hotel room, film and tapes rolling. Anticlimax. A maid answered. Mr Holyoake was out. Could he ring them back? Our élite must behave in this fashion, not because they want to, but because otherwise they are certain to be accused of ‘Uphimselfism’.

With socialists, equality is a matter of political principle, until they reach power, when it’s a question of amnesia. In New Zealand it is a simple fact of group conformity. It is negative not positive. Its basis is a widespread feeling that if we can’t all have something, no one should. Exceptions are made only for no-remittance cars and leprosy.

This is the country of ‘the right thing’. When interviewers confront citizens in the street with microphones they are so anxious to say it that they all say the same thing. Give them a norm and they’ll conform to it, unless its next name is Kirk. The process implies no belief in the norm, simply a considerate desire to avoid embarrassing others or discomforting themselves. Kiwis are virtuous; surveys of church attendances indicate that about a third go regularly, half once a month or more. They are also better ministered, at one per 500 adherents, than they are doctored. Yet all this is not through any yearning for salvation—they’ve got that already. It’s a necessary indication of respectability. Kiwis are honest and law abiding not because they are moral; their approach to the Ten Commandments is like a student to his exam paper—only four to be attempted. Rather they don’t want to step out of line. ‘Thou shalt not be seen to’ is more important than the actual ‘Thou shalt not’.

Big Neighbour is always watching but his ability to enforce his whim comes from the others’ guilt feelings, not his power. The cold-blooded and insensitive can do anything, simply by wearing a suit, attending the Jaycees and carting a prayer book round on Sunday, provided their orgies, drug parties and Red Book readings are kept behind closed doors.

Big Neighbour has positive sanctions only when two conditions are fulfilled. The act must be known. It must make people feel threatened. Then rumours will circulate, accusations will be launched in Truth, the telephone will make odd noises, ministers will announce in Parliament that you attended a meeting of the USSR Friendship Society eighteen years ago. Friends and acquaintances will sidle up to assure you they ‘don’t believe a word of it’ before dashing off to sudden, urgent appointments. The Great New Zealand Clobbering Machine will have trundled into action.

More normally there is a tolerant intolerance simply because of the intimacy. You can hardly be rude to someone you see every day, however many anonymous letters you might write to the press about him. And if intimacy is intolerant, it is also warm and friendly. This is the friendliest country in the world, a characteristic it is not advisable to question if you value your teeth. Everyone knows the story of General Freyberg driving through the New Zealand lines in the desert with a British general. ‘Not much saluting is there,’ says the highly pipped Pom. ‘Ah yes, but if you wave they’ll wave back.’

To make life even more pleasant New Zealand has one of the highest standards of living in the world: second in the car ownership league, fourth in telephones, third in washing machines, second in beer consumption at twenty-five gallons per fuddled capita, and first in tons of soap and number of showers per person. Many of the cars should be in motor museums, the phones don’t have subscriber trunk dialling, the washing machines are prediluvian tubs, the beer is tasteless, and the soap is carbolic. It hardly matters. Wellbeing is more evenly shared here than anywhere else.

This has been achieved with unpromising raw materials. New Zealanders don’t work like Germans, organise like Japanese, or compete like Americans. All they have is a practical flair. The country is too far from anywhere to be natural suppliers and too small to provide a worthwhile market for anyone else. It is too tiny to forge its own destinies and is subject to fluctuations beyond its control with massive internal political repercussions. But for this vulnerability the Continuous Ministry would still be in power (if this isn’t in fact the case). The land has few minerals, just a certain amount of natural beauty waiting to be built on or flooded, and an ability to grow grass. The standard of living depends on the animals unimaginative enough to eat grass and on the world’s willingness to eat them, though if the scientists have anything to do with it, they’ll eat the wool, too, eventually. These are the only valuable exports, although in the past few years the nation has begun to develop a new line which can be expanded in emergency—the export of the limited range of fine quality, locally produced people. Well made New Zealand. And how pleasant the manufacturing process.

Casual observers, after that two-day stay which qualifies them as experts, often assume that the scale of New Zealand’s achievement in the face of the inherent difficulties is the result of a deliberate pursuit of socialism. They call New Zealand the Land of the Long Pink Cloud, or Shroud depending on viewpoint. In fact it’s all been done by accident. People settled there not to build a perfect society, but just to improve their lot. Since they came mainly from working and lower middleclass backgrounds their concept of what they wanted to achieve was the life-style of the groups immediately above them in Britain, the middle class. The goals were modest. (They have continued to think small.) And the methods were practical and workmanlike. There was no ideological plan—they just tinkered as they went along, reducing this little universe to order by organising and regulating it. Then they set out to cut it off from the rest of the world as far as possible. Both methods helped shape the national character.

One of the greatest Kiwi skills is organising bureaucracies. Give them a problem and they’ll set up a committee, or an organisation. They provide welfare through voluntary organisations, with mums forming play-group committees, parents forming PTAs, Bads organising Rotaryisseries or Lion Packs (each desperately occupied in the despairing task of finding any poor and underprivileged to be charitable to). This is the welfare society. Above it hovers the greatest voluntary organisation of all, the State, which is seen as the community in action, rather than the remote abstraction it is elsewhere. The community wants a high and uniform standard of living. The State will provide it with two clever tricks. Full employment eliminates both poverty and the fear of being out of work and endows the people with their casual independence. Family allowances, state housing and welfare benefits also help to provide a level below which it is difficult to fall, a much simpler approach to welfare than President Nixon’s policy of making it illegal to be poor, or the proposal by other American right-wingers to use nuclear weapons in the war on poverty.

Bureaucracy and regulation aren’t enough. The New Zealander also has to live. If economic forces were free to operate, New Zealand would be three farms manned by a skeleton staff. The rest of the people would have to evacuate and leave the country to its rightful owners, Federated Farmers, with just enough others to service their Jaguars. Since there are three million New Zealanders, not just the 100,000 which economic logic would dictate, they have taken the protective measure of building a fence of tariffs and licences round the economy so that a pampered industry can develop.

This careful insulation has annoying consequences. Rabid sectional jealousies develop. Farmers exhibit acute pastoral paranoia when they see the rest of the populace lounging round demanding high wages at the expense of the only productive section (the sheep and the cows). Similarly, employers are bitter at workers who don’t put in longer hours churning out items the market is too small to take. And farmers, employers, workers all combine into a chorus of grumbling about the welfare state, regulations, controls, restrictions and the result of the 3.30.

So vociferous is the chorus you might assume the country is on the brink of civil war or armed uprising. Indeed, large numbers of French arms salesmen went out there after the Biafra war, thinking to find their next potential customer. Also grumbling is a major political sport. Prizes are allocated for it; small ones like a post office or a new school for the short burst, big ones like protection or subsidies for a really sustained effort. The current grumbling league table puts doctors first in both volume and prizes, farmers second. University staffs are now moving up fast, having quickly mastered the art. Geographically it is only fair that Auckland should grow fastest. Its inhabitants have the loudest mouths for grumbling.

The second consequence is that private enterprise is more private than enterprising. It is inefficient. It carries on production in 9,000 small factories where a few big ones producing economically might be more sensible. Industry is expensive; television sets cost twice as much as Japanese imports, though bigger screens may be needed for larger people.

Yet the role of business isn’t to produce cheaply, or efficiently, but to wangle concessions from the government. The most enterprising entrepreneur is he who gets the most support: grants, import licences, or protection. These are the key to profit, not production. Nevertheless the country does export some manufactured goods; in 1969 it even sent $17 worth of musical instruments to Cambodia.

Most of the manufactured exports are potential not real. Entrepreneur and ex-car salesman Ken Slabb wants to exploit the local market for left-handed corkscrews. The market is limited and small-scale production and an inordinate rate of profit will make his product eighty-four times more expensive than imports. The solution is to claim that his main aim is to export millions of left-handed corkscrews every year. With supporting evidence from Ken’s great-uncle and an ex-girlfriend in Australia, poetic submissions are then heard by the Tariff, Development and Upholstery Council, where, despite opposition from the Glove, Mitten and Boottee Trade Association, the council agrees to exclude all left-handed corkscrews to give him a chance to establish himself. Within ten years the price of left-handed corkscrews has gone up 184 times, though sales have trebled because most of those used break on impact with a cork. Ken Slabb has made a fortune and retired to an island in the Bay of Islands, selling out to a British firm of corkscrew manufacturers who used to supply the market before he intervened. The exports have failed to materialise because of unfair trade practices on the part of the Australians and the unexpectedly heavy wage demands of the New Zealand worker. The alternative ending to this story is that prices increase only 180 times and the manufacturer goes bankrupt.

This may horrify you. Visiting IMF teams have been so numbed by it that they have been unable to say anything for months but the name ‘Bill Sutch’ repeated interminably. In fact, of course, New Zealand can live comfortably only by standing orthodox economics on its head. To understand the economic system you have to abandon what you’ve been brought up to regard as sense. Agricultural exports provide enough for all to live on. Kiwis could spend their time blowing bubbles or reading back numbers of Playboy were it not for some deep-seated puritan instinct which conditions them to want to work. So jobs have to be provided. Industry exists not to make things but to make work. The most efficient industry is the one which uses its labour most inefficiently; wharfies make their greatest contribution when seagulling; smokos do more for the economy than shift working. All the jokes about wharfies, like the one who complained to his foreman that a tortoise had been following him round all day, or the aerial photo of Wellington wharves which was ruined because a wharfie moved—all these miss the point. Work is like muck, no good unless its well spread.

Being practical men, New Zealanders are concerned not with hypothetical questions such as would Adam Smith, or even Robert McNamara, approve of our economy, but does it work? It does. The people have jobs, a good standard of living, a car and a lovely home each. Who could ask for more. They are not even concerned with the problem of whether the system could work better. Good enough is better than hypothetical perfection. Anyway the system works so well and has made the inhabitants so contented that they are the world’s most stable, and probably most conservative society.

Seriously, New Zealand is the best place in the world to live. It is called God’s Own Country. Modern theologians may argue whether God is dead. The rest of the world must pose him a lot of problems. Yet if the strain does get too much then he’ll not die. He’ll retire here.

*. See Fishopanhauser and Smith, ‘Conflict Theory and Beer Prices in a Southland Town’. A Ph.D. thesis assessing the relevance of Action Theory to empirical political analysis, including an attempt to establish a basis for determining the relationship between individual behaviour and system attributes. Based on in-depth interviews with 250 drunks.

**. See H. Sheisenhauser and Les Cumberland, ‘Status Attribution, Self Assigned Social Grouping, Inverse Social Mobility with Cognitive Dissidence and the Incidence of Plaster Ducks on Walls’. An exploratory survey based on 2.8 million random interviews with a stratified sample of New Zealanders. Condensed five-volume summary of results shortly available.

THIRD LETTER

STUPENDOUS, FANTASTIC, BEAUTIFUL NEW ZEALAND

(In Black and White)

DON’T THINK of New Zealand as a nation. It is an accidental collection of places whose inhabitants happen to live in much the same fashion and talk the same language; not so much a nation as more a way of life. How tenuous the connections are I realised on decimalisation day. A woman in a Christchurch shop announced that she wasn’t going to bother with this decimalisation rubbish. They were moving to Invercargill next week. Dunedinites think of Auckland as another country. Aucklanders advise South-bound trippers to take enough overcoats and hot-water bottles for the South Pole. Interisland ferry sailings generate as much emotion as a world cruise. It’s as though an umbilical was being severed. At both ends.

New Zealand is a collection of communities, not the metropolitan country you know. In France, Paris sets the tone and controls a centralised machinery of administration. In Japan, Tokyo dominates business and houses a substantial part of the population. In Britain, London dominates; television and newspapers originate there, the social whirl centres there and career ladders end there. New Zealand is different. There is not one main centre but four, and even together they contain only about a third of the population. They are also far apart and very jealous of each other. Even if they could develop collective pretensions they are all jealously watched by a league of little sisters. Oamaru and Invercargill won’t stand for much from Dunedin except bad television programmes; Palmerston North keeps a close eye on Wellington. In any case the eighteen biggest urban areas contain just over half the population. All the other places have claims of their own, too.

In Britain everywhere outside London carries the stigma of being provincial. New Zealanders work on the assumption that all places are equal, though the growth of Auckland may have opened up the possibility that some are more equal than others. Life has a local focus. Different places view different television programmes, look at different newspapers and listen to different radio programmes. To be a Timaruvian means as much as to be a New Zealander. The only reason that travellers identify themselves overseas as New Zealanders is because no one seems to have heard of Waipukurau or Totaranui. Of course they draw together as a nation for the occasional catharsis—an All Black victory, a royal tour. Then they fall back into competing localities. This competition is all the more vigorous because it is one of the few notes of diversity in a uniform community.

Farmers live in the same kind of boxes as the rest; the boxes just happen to be in the middle of fields. Social habits are the same everywhere, though some have a longer drive to the pub. Nearly everybody looks out on the same jungle of tottering telegraph poles and tangled wires; there could be sewerage pipes to look at, too, if governments had been able to devise a safe method of stringing them among all the other dangling paraphernalia. New Zealanders are all campers on a lovely landscape and the main element of difference in their lives is the accident of which camp site they happen to have picked. Wherever it is, you must remember one basic rule: the place where you are now is the best in New Zealand, its people the friendliest, its streets the cleanest, its flower beds the prettiest. Everyone else is out to do it down. You must defend it to the last mixed metaphor against all criticism, however justified.

This state of affairs exists because every place is competing against every other. Parliament may go through routine motions of party debate but it only comes alive when it gets down to the real issues—the quality of the pies in the railway refreshment room at Clinton … whether Gisborne has got its fair share of Golden Kiwi grants as well as its more than fair share of everything else … would a chain and a twelve-pound ball encourage the doctor to stay in Hokianga … should the Christchurch City Council be allowed to plant concrete in Hagley Park. MPs aren’t a national élite, they are local delegates, there to voice local demands.

Cabinets are similar. Indeed the requirements of geographical spread is the only conceivable explanation of the presence of some ministers, particularly ones from Dunedin. Cabinet decides the really important priorities. If Wanganui gets the eighteenth veterinary school, will the fourth college of chiropractors satisfy Hastings? If Auckland is to have a container port as well as an international airport, what can be done to conciliate Reefton’s claim, short of rebuilding it on the coast? Perhaps a notional container port? For years governments have been praying for the ultimate dreams of localism, the garden shed university, the vertical take-off plane which can land anywhere and give everywhere an airport. Shortsightedly they have failed to realise that both would merely unleash even more bitter arguments by fragmenting parochialism into long wrangles over whose shed is to be used, whether the airport should go into the front garden or the back, who is to have the lemonade concession.

The parochial fight spills over everywhere. Imagine the fate of television directors exposed to constant demands to do a programme on Backblocksville, and then, if they do so, to constant threats ranging from pre-frontal lobotomy to castration because they didn’t show the floral clock in the gardens. People connected with the old TV ‘Compass’ programme are still doing thirty-mile detours round Alexandra because a 1965 programme omitted to mention that it was the most beautiful town in New Zealand. Still, perhaps that’s easier than the thirty-mile detour round everywhere else which would have been necessary if they had.

Imagine, too, the torments of royal tour itinerary planners, and the scandal which would have been produced if the private comment of one Governor-General that Oamaru and Timaru were like Tweedledum and Tweedledee had got out. Local government reform is impossible in a country where every place with more than a hundred people has to be a city, everywhere with more than five a borough, leaving to all the others the incentive to reproduce quickly. Local government is a system of dignity not function, conferring status on places and an elective honours list on the locally prominent. At 10,000 councillors and board members there are more per capita magna than anywhere else. In the smaller centres talk to everyone you meet as if he were the mayor. If you’re wrong he’ll certainly be on the council, unless you talk to yourself. The whole mistake of local government reformers has been to swim against the tide by trying to create bigger units and make mayoral chains lighter on the rates. A policy of ‘Every man his own mayor’ would be better.

Conversation has to make due deference to locality. Much of it is the routine exchange of stereotypes, decking out the petty struggle between localities in the trappings of romance. Everyone in Dunedin wears a kilt. Everyone in Nelson has one eye. So here’s a basic introduction which might help you to a better understanding, even if it does place me under the unfortunate obligation of mentioning every hamlet. The ultimate New Zealand book, and the best loved, is the Electoral Roll. The plot may be dull but everyone gets a mention.

Precedence among New Zealand cities goes to Auckland, believed by many, over a half a million in fact, to be the Queen City. Yet Auckland also has a large heterosexual population, even if there are some who believe that a pretty girl is like a malady. The city began as the sweepings of Sydney. Even now it has many of the characteristics of an Australia for beginners.

Auckland falls between two stools—too big for the rest of New Zealand, too small to provide a genuinely big city existence. It is essentially a main street surrounded by thirty square miles of rectangular boxes, covering as great an area as London to far less purpose. Yet size is still the key to Auckland. It confers pretensions: the morning paper modestly takes the name of the whole country, wealth seems easier to come by and is certainly more flamboyant. This is a city of self-made men who worship their creator. Its Joneses are more difficult to keep up with. One can only be thankful that Auckland isn’t actually the capital. With this further dignity its inhabitants would be insufferable. Even now the snowball processes of growth make Auckland almost unbearable, as well as threatening to shatter the precarious federal balance that is New Zealand.