Полная версия

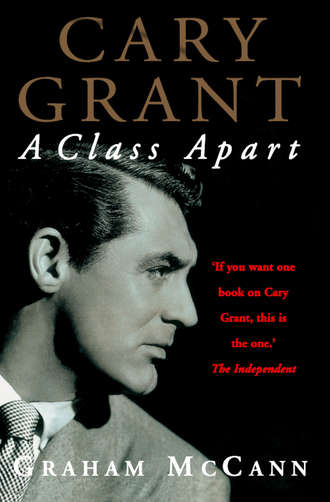

Cary Grant: A Class Apart

That year was the most dismal one for legitimate theatre in the US for two decades. Almost half of all Broadway theatres were closed. The only work that Archie Leach could find was at the open-air Municipal Opera in St Louis, Missouri, where J. J. Shubert produced a summer-long series of musical revivals. Although Cary Grant later recalled the 8,000-seat amphitheatre in Forest Park as being ‘delightful’,50 and the summer season as ‘glorious’,51 it was gruelling work, with a new role to be learned every two weeks. The plots were often extravagant, the productions lavish and the lighting effects, in particular, were spectacular. Audiences were rather less discriminating than on Broadway, but they appreciated professional performances. Leach, usually playing the romantic lead, stood out as a darkly handsome young man. Local reviews were generally positive. He was noticed. When the season ended, and Leach returned to New York, he was invited to appear in a one-reeler movie entitled Singapore Sue. He was engaged on 8 May 1931,52 for six days, by the Paramount Public Corporation; the movie was shot at Paramount’s Astoria Studio, and he was paid $150 for his performance.

In the 1930s, short subjects served not only to flesh out an exhibitor’s bill, but also allowed the studios (particularly Paramount and Warners, who both had major production centres in New York which enabled them to lure stars from Broadway and vaudeville) to test new talent inexpensively. Singapore Sue was not destined for any special promotion, but it was, none the less, the first serious opportunity that Archie Leach had to attract the attention of Hollywood producers. He played one of four American sailors visiting the Chinese character actor Anna Chang’s café in Singapore. Dressed in a white tropical uniform, handsome in a rather over-ripe way and wearing make-up that made him appear eye-catchingly pale, he smiled falsely and mumbled, through clenched teeth, his few lines of dialogue without any conviction. It was, quite clearly, a discomforting experience, and one which remained a sufficiently painful memory to cause Cary Grant in 1970 to seek to persuade the organisers of the Academy Awards tribute to him to omit the planned excerpt from Singapore Sue.53 His friend Gregory Peck, who was president of the Academy at the time, sympathised:

In that early shot Cary hadn’t acquired the poise and confidence, the kind of looseness before the camera that he later had. He still looked like English music-hall. I know how I would feel if someone showed a lot of footage of me before I had smoothed out my craft.54

Nothing came of the work.55 In August 1931, Leach asked to be released from his Shubert theatre contracts. The Shuberts obliged. At the end of that month he was engaged to play a character named Cary Lockwood opposite Fay Wray in her husband John Monk Saunders’s play Nikki. It opened at the Longacre Theater in New York on 29 September 1931. Leach was paid $375 for each of the first three weeks, and $500 per week for the remainder of the run. The show, however, did not endear itself to audiences for whom the theatre was now an expensive luxury, and, although it was moved to the George M. Cohan Theater in a desperate bid to save it, Nikki closed after only thirty-nine performances.

In November 1931, shortly after Nikki closed, Archie Leach sub-let his small apartment and decided, along with his friend Phil Charig (who had written the music for the show), to visit California. Having worked steadily for more than three years, he felt he could now afford to take a vacation. Fay Wray, to whom he had become very close during the run of the show, had been offered a part in the movie that RKO Radio was planning from Edgar Wallace’s story King Kong. She had invited Leach to follow her.56 Other people had, at various times during the previous two years, encouraged him to move on and attempt to establish a movie career in Hollywood, and now, after yet another show had ended – in his view – prematurely, the time, at last, seemed right.

CHAPTER V Inventing Cary Grant

Yes, despite his appearance, he was really a very complicated youngman with a whole set of personalities, one inside the other like a nest ofChinese boxes.

NATHANAEL WEST

I guess to a certain extent I did eventually become the characters I wasplaying. I played at being someone I wanted to be until I became thatperson. Or he became me.

CARY GRANT

If Archie Leach, as he left New York for Hollywood, had come to think of himself as a self-made man, then Cary Grant, as he stepped out into the Southern Californian sunlight, would come to think of himself as a man-made self. Archie Leach had learned a great deal in a short period about how to perform, but, so far, he had learned little about how best he might use this technical knowledge to lend a certain distinctiveness to his own performances. Cary Grant would bring an unusual, attractive, imaginative personality to complement the existing solid technique. The change of name, in itself, was banal; it was common practice in Hollywood, where words were put to the service of pictures and one’s name functioned as a sub-title for one’s image. The change of identity, however, was profound; the new name heralded a new self.

Archie Leach did not arrive in Los Angeles with any great expectation of such a rapid and dramatic transformation. He was hopeful of employment in Hollywood, but he was not desperate; he knew that the Shuberts were eager to use him again, should he wish, or need, to return to Broadway. He could afford, therefore, to approach this new challenge with enthusiasm rather than trepidation.

There are, perhaps predictably, several versions of how Archie Leach managed to secure for himself a studio contract. One account, which was popularised by Mae West, has it that she ‘discovered’ him when he was a humble extra on the Paramount lot.1 This is quite untrue; indeed, it was a canard that continued to infuriate Cary Grant whenever he saw it in print.2 He was never an extra, and he had made seven movies before he first appeared with Mae West. Another version – more plausible but still with no documented evidence to support it – was put forward by Phil Charig: according to his account, he took Archie Leach with him when he was summoned for an interview at Paramount’s music department, and, although he was not offered a job, the interviewer was sufficiently impressed by Leach’s good looks to recommend him for a screen test.3 There is, however, another version which, since it originated with Grant himself and there is no obvious reason to doubt him on this matter, may be regarded as authoritative: according to Grant, a New York agent – Billy ‘Square Deal’ Grady of the William Morris Agency – gave him the office address in Hollywood of his friend Walter Herzbrun, and Herzbrun, in turn, introduced him to one of his most important clients, the director Marion Gering.4

Archie Leach did not just have handsome features – plenty of other young, out-of-work actors in Los Angeles at that time were that good looking – he also had genuine charm. It is clear that Archie Leach found it remarkably easy to find people who were able and willing to support his embryonic career. As had happened in New York, Leach became a popular new guest at Hollywood social occasions, and it was not long before he had the opportunity to impress a number of producers and directors. His new, unofficial patron Marion Gering was planning to screen-test his wife, and he thought that Leach could play opposite her. Gering took Leach to a small dinner party at the home of B. P. Schulberg, the head of production at Paramount’s West Coast studio. Schulberg was, it seems, happy to accede to Gering’s request, and a screen test and the offer of a long-term contract (worth $450 per week) were the results.

Archie Leach had achieved, with what seems like remarkable ease, the basis for a movie career. Before he could begin acting in any movies, however, he first needed to work on his identity. As with many young contract players, the studio questioned the marquee value of his name: ‘They said: “Archie just doesn’t sound right in America.’” ‘It doesn’t sound particularly right in Britain either,’ was his rather embarrassed reply.5 He was told, without any intimation that the matter might be open to negotiation, that ‘Archie Leach’ was unacceptable, and was instructed to come up with a new name ‘as soon as possible’.6 That evening, over dinner with Fay Wray and John Monk Saunders (the author of Nikki), it was suggested that Leach might adopt the name of the character he had played in their show: Cary Lockwood. Leach liked ‘Cary’ as his first name, but he was told by someone at the studio that there was already a Harold Lockwood in Hollywood,7 and so the search for a new surname continued.8 The studio advised him to choose a short name: it was the era of Gable, Cooper, Cagney and Bogart. A secretary gave Leach the standard list of suggestions which had been compiled for such a purpose. ‘Grant’, according to his own recollection of the deliberations, was the surname which ‘jumped out at me’.9

Paramount, it seems, was equally satisfied with the combination. ‘Cary’ sounded pleasingly ambiguous, a supple name which, when pronounced to rhyme with ‘wary’, could suit a sophisticated image, and, when pronounced to rhyme with ‘Cary’, could fit with a more plebeian persona. The name’s new owner never seemed particularly interested in proposing a definitive pronunciation: some of his friends, such as Alfred Hitchcock, favoured the former, while others, such as David Niven, favoured the latter (he himself managed, typically, to find a subtle via media, and he only ever protested when anyone attempted to call him ‘Car’). ‘Grant’, on the other hand, sounded reassuringly American; it had more simple and solid connotations, a nod perhaps to the Hero of Appomattox, General Ulysses S. Grant, eighteenth president of the United States. Someone noticed that Cary Grant’s initials were the same as Clark Gable’s and the reverse of Gary Cooper’s; it seemed a good omen – Gable and Cooper were the most popular matinee idols of the day.

Cary Grant was born, in effect, on 7 December 1931,10 the day that he signed his Paramount contract and consigned ‘Archie Leach’ to relative – but by no means complete – obscurity at the age of twenty-seven years and eleven months. Cary Grant was not a new man, but rather a young one with the rare opportunity to restyle himself in a manner which would suit his aspirations. The name change itself was a fairly routine, pragmatic decision by the studio; it was not intended as an invitation to Archie Leach to embark on any profound voyage of self-discovery. Paramount had already decided who Cary Grant should be: a cut-price, younger, dark-haired substitute for Gary Cooper.11 Cooper had joined Paramount in 1927; by 1931, he was complaining that he was being worked too hard. While he was filming City Streets that year, he suffered a near collapse from the combined effects of jaundice and exhaustion. When the movie had been completed, he left for Europe, and began to spend more time with the Countess Dorothy di Frasso than his studio felt was desirable. Archie Leach, smoothed out into the more refulgent form of ‘Cary Grant’, was to be used to remind Cooper – gently at first – that he was not quite as distinctive nor as valuable as he might have thought he was. The two men did have a number of things in common: both had English backgrounds (Cooper’s parents were both English, and he had been educated in Bedfordshire12); both were physically powerful men who could also show their vulnerability; and both were versatile enough to play comic as well as romantic roles.

Cary Grant, it was reasoned, could be groomed for stardom by taking the ‘Gary Cooper roles’ that Gary Cooper turned down, and, by playing on the perceived similarity between the two men, Paramount hoped that Cooper’s ego could be held in check by the constant presence of a possible replacement at the studio. A fan magazine of the time – possibly with some covert encouragement from Paramount’s publicists – noted that ‘Cary looks enough like Gary to be his brother. Both are tall, they weigh about the same, and they fit the same sort of roles.’13 Cooper had been warned. It was a common tactic employed by all studios at the time to prevent their most popular stars from becoming too ‘difficult’: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, for example, had brought in James Craig as a threat to Clark Gable, and Robert Young as a threat to Robert Montgomery. It was good insurance. If Gary became too demanding, Cary could take over (only a modest dash would need to be erased on the dressing-room door); it was considered unlikely, and, as often happened in similar cases elsewhere, it was probably thought more likely that Cary Grant would become a useful romantic lead in a string of relatively modest movies.

Cary Grant, however, had a quite different outlook on the possibilities opened up by his sudden change of identity. He did not wish to live indefinitely within quotation marks; he wanted to create a ‘Cary Grant’ that he could grow into. Whoever this ‘Cary Grant’ was to be, he would have to be someone who seemed real to Archie Leach as well as to others: ‘If I couldn’t clearly see out, how could anyone see in?’14 All that he started with, he admitted, was a façade, and ‘the protection of that façade proved both an advantage and a disadvantage’.15 It offered him both the chance to change and an excuse not to change. Archie Leach wanted to change. The playwright Moss Hart remembers him back in his New York days, mixing with a group of ‘have nots’ at Rudley’s Restaurant on 41st Street and Broadway. According to Hart, Archie Leach had appeared to be ‘a disconsolate young actor’ whose ‘gloom was forever dissipated when he changed his name to Cary Grant’.16

Archie Leach saw his reincarnation as ‘Cary Grant’ not as the end of his self-reinvention but rather as the start of it. The writer Sidney Sheldon, who came to know and work with Grant in the forties, used him as the prototype for Rhys Williams, a character in the novel Bloodline; Williams is described as ‘an uneducated, ignorant boy with no background, no breeding, no past, no future’, but, with ‘imagination, intelligence and a fiery ambition’, he transforms himself from ‘the clumsy, grubby little boy with a funny accent’ into a ‘polished and suave and successful’ man.17 Archie Leach was eager to learn, to absorb as much as he could from the places and people he encountered. His lack of formal education remained one of his lifelong regrets.18 Since his arrival in the US, he had made a point of making the acquaintance of people who were gifted and highly educated. Rather like the character in Bloodline, he ‘was like a sponge, erasing the past, soaking up the future’.19 He was not ashamed of his working-class background, but he did want to take every opportunity to pursue the project of self-improvement; he was, in part, eager to educate himself, but also he was reacting, with bitterness, to the memory of the routine humiliations suffered by himself, his family and his friends back in England. He studied other people’s dress sense, table manners, gestures and accents. He was not going to be ‘caught out’. The composer Quincy Jones, who formed a friendship with him in later years, remarked that when he was growing up, ‘the upper-class English viewed the lower classes like black people. Cary and I both had an identification with the underdog. My perception is that we could be really open with each other because there was a serious parallel in our experience.’20 John Forsythe, who acted alongside him in the forties, made a similar point: Archie Leach had been ‘a poor kid. He did scrape his way to the top. That meticulous quality he had – knowing how to best use himself – was one of the key things to his nature.’21

The idea of America – its promise of liberty and equality – inspired Archie Leach, as it had inspired many other English people from similar backgrounds. Betsy Drake, who became Cary Grant’s third wife, recalled that ‘in Cary’s day you got nowhere – nowhere – with a lower-class accent. The fact that he survived all that speaks very well for him.’22 Though America had its own casual snobberies, it was, none the less, considerably more democratic in outlook and disposition than the England that Archie Leach had grown up in. Categories in England were particularly rigid then, and social distinctions emphatically made and scrupulously preserved. In America, on the other hand, Archie Leach could, to some extent, avoid such potential disadvantages. Only an expert in contemporary English class distinctions could have contemplated slotting him firmly into a particular niche; to most people he was just a good-looking and personable young man.

Archie Leach had some sense of what kind of person he wanted Cary Grant to be. Glamorous, for instance. Archie Leach wanted Cary Grant to be the epitome of masculine glamour. To this end his first chosen role-model was Douglas Fairbanks. He had met Fairbanks before he even set foot in America. Fairbanks and his wife, Mary Pickford, had been passengers on the RMS Olympic on the same voyage to the US as Archie Leach and the rest of the Pender troupe. The couple were returning to America after their much-publicised six-week honeymoon in Europe. Fairbanks fascinated Archie Leach. Tall, dark and handsome, an international screen idol, a ‘self-made man’ (with just a little help from Harvard), a fine athlete and, as his young admirer noted, ‘a gentleman in the true sense of the word. A gentle man. Only a strong man can be gentle.’23 Archie Leach was thoroughly impressed by Fairbanks, off screen as well as on; Fairbanks symbolised the kind of man – and star – that the then still somewhat gauche teenage Archie Leach wanted one day to become. What is more, Archie knew enough of Fairbanks’s biography, gleaned from movie magazines and newsreels, to see that they had much in common: disrupted and largely unhappy childhoods, alcoholic fathers, acrobatic training, apparently limitless high spirits and a capacity to enjoy their own good luck. Fairbanks had triumphed; he had achieved fame, wealth and power, as well as marrying ‘America’s sweetheart’.24 ‘For a man coming out of darkness into light,’ commented the critic Richard Schickel, ‘there was, possibly, a promise in Fairbanks.’25

At one point, late on during the crossing, Archie Leach found himself (probably less fortuitously than he later liked to suggest) being photographed alongside his hero during a game of shuffleboard: ‘As I stood beside him, I tried with shy, inadequate words to tell him of my adulation. He was a splendidly trained athlete and acrobat, affable and warmed by success and well-being.’26 Archie’s glimpses of Fairbanks on that first Atlantic crossing provided him with his initial, and possibly most enduring, image of modern elegance and style. Cary Grant always attributed his almost obsessive maintenance of a perpetual suntan to that first sighting of Fairbanks’s deeply bronzed complexion,27 and he was also equally impressed by the relatively thoughtful and understated elegance of Fairbanks’s dress sense (he was not the only one: many of the studio bosses had started out in the clothing trade, and there were few sights more likely to have them purring with delight than that of a well-tailored suit28). An Anglophile, Fairbanks had his suits made in Savile Row by Anderson & Sheppard, his evening clothes by Hawes & Curtis, his shirts by Beale & Inman and his monogrammed velvet slippers by Peel. Grant never forgot the subtle precision of that celebrated sartorial flair. Ralph Lauren has said that, years later, Grant described, in minute detail, how Fairbanks looked, and he urged Lauren to make a double-breasted tuxedo ‘like the one worn by Fairbanks, same lapel and all’.29

Archie Leach was aware, however, that he could not, and should not, simply replicate the Fairbanks look. Cary Grant could not be another Fairbanks. Fairbanks was, at least on the screen, an all-American hero and Cary Grant, whatever, whoever, he might become, was never going to pass for an all-American hero. Gary Cooper would be able to grow into the role of the westerner, his voluptuous, gentle-looking face changing gradually – as though it had long been left thoughtlessly outside at the mercy of the elements – into a harder, rougher complexion, but Cary Grant could not go far in that particular direction. If Cary Grant’s future was American, his lineage was English. He could change the way he looked rather more effectively, and speedily, than he could change the way he sounded. His accent, when he arrived in Hollywood, was the oddest thing about him. Nobody talked like that, not even Archie Leach in earlier years.

There is no reason to believe that Archie Leach, during his childhood and early adolescence, sounded in any way different from other working-class Bristolians. There are, indeed, some who claim to be able to discern the distinctive ‘burr’ of his old Bristol accent beneath the assumed American tones.30 It seems likely that Archie Leach’s accent first began to change during the period he spent in London with the Pender troupe. It was not just that he was, at the impressionable age of fourteen, exposed to the distinctive dialects associated with South London, but also, more specifically, that he was drawn into the London music-hall community, which had developed its own semiprivate patois, something described by one performer as ‘a mixture of Cockney, Romany and Hindustani’.31 Archie Leach, in time, would speak in his own odd hybrid of West Country and mock-cockney, with an increasingly distinctive staccato enunciation. Ernest Kingdon, his cousin, believed that this peculiar accent was to some extent the result of the fact that he was ‘trying to maintain English speech, and he had trouble with his diction … It’s not cultured English talk [but] very precise … as if he’d been taught elocution.’32 This very individualistic way of speaking was probably made even more noticeable during the years Leach spent touring the music-halls in Britain and America with the Penders. Peter Honri, a member of one of Britain’s most famous music-hall families, has noted that the so-called ‘music-hall voice’ relied not so much on volume as on ‘pitch and resonance’ – it was ‘a voice with a cutting edge’.33

Archie Leach, as he struggled to survive in New York, realised that being – or, more pointedly, sounding – English limited the number of stage roles he could, with any seriousness, audition for.34 ‘I still spoke English English, and I knew that to get jobs here, I’d have to learn American English.’35 He was not trying consciously to erase the sounds that associated him with a certain geographic and class background; he was simply trying to make himself more employable in his new environment. As Richard Schickel has argued, he was probably aiming not for affectation but rather for ‘something unplaceable, even perhaps untraceable’, a malleable accent that could lend a ‘democratic touch of common humanity’ to an aristocratic role and a ‘touch of good breeding’ to the more raffish parts.36

He did his best, and, of course, his accent had already begun to change during those first formative years he had spent in the United States,37 but the transformation process was both slow and incomplete. Some New Yorkers during this time mistook him for an Australian,38 and a number of his colleagues, for a brief period, took to calling him ‘Boomerang’, ‘Digger’ or ‘Kangaroo’ Leach (years later, in Mr Lucky, he referred back to this strange misconception, having his character explain his use of cockney rhyming slang by saying, ‘Oh, it’s a language I picked up in Australia’). Although his accent, once he had settled in Hollywood, grew gradually into its now-familiar transatlantic timbre, it continued to strike some American admirers as beguilingly exotic. The critic Richard Corliss, for example, writing on the occasion of Cary Grant’s death, recalled the ‘cutting tenor voice that refused to shake its Liverpool origins’39 (which is rather like suggesting that James Stewart never quite managed to lose his Texan twang). Grant himself remained appealingly unpretentious and self-effacing when referring to his accent: when Jack Warner offered him Rex Harrison’s role in the movie version of My Fair Lady, he exclaimed, ‘I cannot play a dialectician – a perfect English teacher. It wouldn’t be believable … I sound the way ’Liza does at the beginning of the film.’40