Полная версия

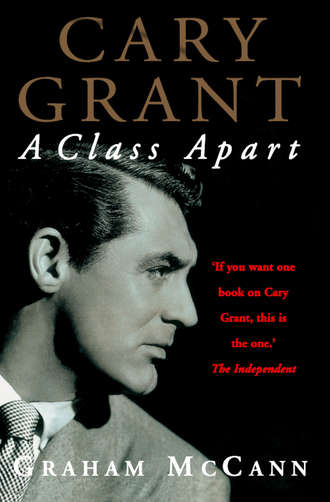

Cary Grant: A Class Apart

Elsie Leach, it is true, did not accept her son’s offer – which was put to her on more than one occasion – to move to California, but her refusal was prompted by reasons other than any alleged ill-feelings towards her son. At the end of his life, Grant explained:

She wouldn’t join me in America. She told me: ‘Never lived anywhere but Bristol. Don’t want to [leave], only place I know.’ At her own request she lived in a nursing home but we kept her house although we knew she would never return there. I didn’t want to get rid of it. It would have seemed like I was packing her off.35

Elsie was, it seems, as concerned about her son as he was about her. In 1942, when war prevented him from flying over to see her, she wrote to him: ‘Darling, if you don’t come over as soon as the war ends, I shall come over to you … We are so many thousands of miles from each other.’36 A friend of Elsie’s recalled seeing two large chests of food which had been gifts from Grant. When she was asked why they remained unopened, Elsie is said to have replied, ‘I want to have them until they’re really needed … You never know … Cary might be hard up one day.’37 When Grant tried, unsuccessfully, to persuade her to let him hire someone to do her housework for her, he was amused and impressed rather than upset by her negative response: ‘she avers that she can do it better herself, dear, that she doesn’t want anyone around telling her what to do or getting in her way, dear, and that the very fact of the occupation keeps her going, you see, dear’.38

The earliest letter from Elsie in Cary Grant’s papers is dated 30 September 1937, sent from Bristol to Hollywood, and it gives one the impression of a much warmer, caring and humorous person than many biographers have described:

MY DEAR SON,

Just a line enclosing a few snaps taken with my own camera. Do you think they are anything like me Archie? I am still a young old mother. My dear son, I have not fixed up home waiting to see you. No man shall take the place of your father. You quite understand. I am desperately longing waiting anxiously every day to hear from you. Do try and come over soon …

Fondest love, your affectionate MOTHER.39

In her letters and postcards – and Grant saved hundreds in his personal archive – she was usually rather garrulous and good-natured, addressing her son as ‘Archie’ or ‘My Darling Son’ and closing with ‘Kisses’, ‘Fondest Love’ or ‘Your Affectionate Mother’.40 Grant, in turn, cabled or wrote to her regularly,41 usually addressing her as ‘Darling’, ending with ‘Love Always’ and ‘God Bless’, and signing his name as ‘Archie’. In one letter, sent in 1966 shortly before the birth of his (and Dyan Cannon’s) daughter, Grant wrote:

Watching, and being with, my wife as she bears her pregnancy and goes towards the miraculous experience of giving birth to our first child, I’m moved to tell you how much I appreciate, and now better understand, all you must have endured to have me. All the fears you probably knew and the joy and, although I didn’t ask you to go through all that, I’m so pleased you did; because in so doing, you gave me life. Thank you, dear mother, I may have written similar words before but, recently, because of Dyan, the thoughts became more poignant and clear. I send you love and gratitude.42

Phyllis Brooks, who was once engaged to Grant in the late 1930s and who remained a close friend, remembered him being reunited with Elsie: ‘Cary called his mother a dear little woman. But he didn’t talk much about her. I didn’t probe. It was such a traumatic thing to have happen to anybody.’43 If the reunion had been an act, prompted by fears of adverse publicity, he seems to have invested an unnecessary amount of time, energy and emotion in maintaining the union during the next thirty-five years. It seems likely that Grant and his mother did, slowly, develop a relationship that was, in the circumstances, relatively stable and mature.

It is probably true that he had found it much easier to feel affection for his father.44 He had, after all, enjoyed an uninterrupted relationship with him, and, after his mother’s disappearance, he may have come to regard his father, like himself, as a victim of that traumatic episode.45 His mother, it seemed at the time, had, without any explanation, deserted him, whereas his father had stayed and raised him. When Elias died, his son expressed the belief that his death had been ‘the inevitable result of a slow-breaking heart, brought about by an inability to alter the circumstances of his life’.46 It would be wrong, however, to accept uncritically the common perception today of Elias as the deferential working-class man and Elsie as the somewhat snobbish woman with grand ambitions, just as it would be wrong to believe that Grant sided consistently and completely with one or the other of his parents. He once said that, when he looked back on the family arguments that dominated his childhood, he felt unable to ‘say who was wrong and right’.47 Both Elsie and Elias Leach possessed a strong sense of working-class pride: in Elsie, this showed itself in her determination to avoid giving anyone an opportunity to regard her family as ‘common’, as well as in her dreams of financial security and her hopes for her son’s social advancement; in Elias, this pride evidenced itself in more prosaic and pragmatic ways, such as in his advice to his son to buy ‘one good superior suit rather than a number of inferior ones’, so that ‘even when it is threadbare people will know at once it was good’.48 Elsie craved prosperity whilst Elias would have settled for the appearance of prosperity; Archie respected his mother’s boundless determination, as well as sharing some of her aspirations, and he also sympathised with his father’s gentle stoicism.

Eventually, Cary Grant came to look back on his childhood, and both of his parents, with a generous spirit: ‘I learned that my dear parents, products of their parents, could know no better than they knew, and began to remember them only for the most useful, the best, the nicest of their teachings.’49 According to one of his friends – Henry Gris – it was only relatively late in his life that Grant ‘realised the depth of his guilt complex about his mother’s disappearance. He believed he was the subject of his parents’ many bitter quarrels.’50 Archie Leach, however, during those traumatic months following the mysterious disappearance of his mother, was unable to come to terms with what had really happened to his family; he could only attempt to adjust to what he thought had happened, and he thought that his mother had deserted him. ‘I thought the moral was – if you depend on love and if you give love you’re stupid, because love will turn around and kick you in the heart.’51

CHAPTER III A Place to Be

Regardless of a professed rationalisation that I became an actor in orderto travel, I probably chose my profession because I was seeking approval,adulation, admiration and affection: each a degree of love. Perhaps nochild ever feels the recipient of enough love to satisfy him or her. Oh,how we secretly yearn for it, yet openly defend against it.

CARY GRANT

Our dreams are our real life.

FEDERICO FELLINI

Archie Leach’s adolescence was marked by absence: the absence of his mother, the absence of a stable home life, the absence of money, the absence, it seemed, of a promising future. Not long after his mother’s disappearance, his world was disrupted again: Britain was at war, and material conditions grew even worse for working-class families. His father, it seems, simply withdrew himself from his son’s life. There was no open breach; there was just a vague and gentle separation. They left the house at different times – Elias for work, Archie for school – and they returned at different times. They seldom saw each other. Archie became, in effect, a latch-key child.

In September 1915, at the age of eleven, he won a scholarship to the local Fairfield Grammar School1 – a gabled, red-brick establishment about ten minutes’ walk from Picton Street. The Liberal government of the time offered ‘free places’ to a limited number of children whose parents could not afford to contribute financially to their education.2 Archie still had to pay for his books, school uniform and other necessities, however, and, in the absence of his mother, he soon came to suspect that he would probably not be able to get through Fairfield on the little money that his father gave him. As a result, his ‘aspirations for a college education slowly faded’.3

Elsie Leach’s smart young son was now, according to one of his former classmates, ‘a scruffy little boy’4 who was a promising scholar and a good athlete, but who also had a mischievous streak and was often a disruptive influence. ‘It depressed me to be good, according to what I judged was an adult’s conception of good’, Grant recalled, ‘and matters around me were not going well.’5 When Cary Grant made his triumphant return to Bristol on a visit in 1933, Archie Leach’s old teachers told reporters of their memories of ‘the naughty little boy who was always making a noise in the back row and would never do his homework’.6 The irascible piano teacher whom Archie was obliged to visit had taken to rapping the knuckles of his left hand with a ruler (he was naturally left-handed,7 which caused him to struggle sometimes to play as she instructed). ‘My head seemed stubbornly set against the penetration of academic knowledge,’8 although he admitted, grudgingly, that he quite enjoyed studying geography, history, art and chemistry. What he did become was an avid reader of comics, such as The Magnet and The Gem, as well as a popular and eye-catching footballer (playing in goal and experiencing the ‘deep satisfaction’ of being cheered when making a good save – ‘one of those fancy ballet-like flying jobs’9). It was, in fact, as a result of his increasingly uninhibited sporting exploits that he suffered an accident that would alter his appearance in a subtle way: he snapped off part of a front tooth when he fell over in the school playground; the gap closed up in time, but he was left with only one front-centre tooth.10 Similar – if less dramatic – mishaps followed. His teachers began to give up on him: ‘I was not turning out to be a model boy.’11

He found an additional outlet for his energies in the 1st Bristol Scout troop. At the end of his first year at Fairfield he volunteered for summer work wherever his Boy Scout training could be used for the war effort: ‘I was so often alone and unhappy at home that I welcomed any occupation that promised activity.’12 He was assigned to working as a messenger and guide on the military docks at Southampton. For two months he watched thousands of boys not much older than himself sail off towards France; some had already lost an arm or a leg in combat but were being sent back for a second time. It was a poignant experience for him, but it was also, in an odd way, an exhilarating period in his life. When he returned to Bristol, he began to spend time at the docks, where schooners and steamships sailed right up the Avon into the centre of the city. ‘You always had a sense that Bristol was a port, a gateway to somewhere else,’ he said, and, seeing the ships ‘that could take you all over the world’, he came to see the city as ‘a place you could leave, if you wanted to, and, at that age, I did.’13 He was restless and lonely, and it appears that he contemplated signing on as a cabin-boy until he discovered that he was too young.14 Although, years later, he described Bristol as ‘one of my favorite places in the world’,15 he admitted that, at the time, ‘I didn’t like it where I was, and I wanted to travel’.16

Back at the dark, quiet, cramped house in Picton Street, he was aware that his father, on those irregular occasions when he saw him, was growing increasingly withdrawn and melancholic. ‘He was a dear sweet man, and I learned a lot from him,’17 but as a father he no longer exerted much influence on Archie’s life. The shadow of Elsie hung over them both. Years later, Cary Grant wrote of a long-held desire to ‘cleanse’ himself ‘perhaps of an imagined guilt that I was in some way responsible for my parents’ separation’.18

An opportunity to escape from the emptiness of his home life opened up unexpectedly when he encountered an electrician who was helping out in the school laboratory as a part-time assistant. Grant remembered him as a ‘jovial, friendly man’19 whose attitude towards his own family was considerably more responsible and positive than that of Elias Leach. This unnamed benefactor took a kindly interest in the bright but rather pathetic young boy who was clearly eager for companionship. He was also working at that time at the Hippodrome, Bristol’s newest variety theatre, which had opened in 1912; a fully electrified theatre was still something of a novelty in those days, and he offered Archie the chance to explore the house that he had helped to wire. Archie, without any hesitation, accepted:

The Saturday matinee was in full swing when I arrived backstage; and there I suddenly found my inarticulate self in a dazzling land of smiling, jostling people wearing and not wearing all sorts of costumes and doing all sorts of clever things. And that’s when I knew! What other life could there be but that of an actor? They happily travelled and toured. They were classless, cheerful and carefree.20

From that moment on, Archie Leach spent as much time as he possibly could at the theatre. The electrician introduced him to the manager of the Empire, another Bristol theatre, where he was invited to assist the men who worked the limelights. There he began to learn the ways of showbusiness people, absorbing the lore of the theatre. This unofficial job came to an abrupt and embarrassing end when, working the follow spot from the booth in the front of the house, he accidentally misdirected its beam, revealing that one of an illusionist’s tricks was achieved with the aid of mirrors. Archie reappeared, his enthusiasm undimmed, at the Hippodrome, where he became a familiar sight, running errands and delivering messages backstage. His father and grandmother were, it seems, quite content to allow him to pursue his new activity without any interference. ‘I had a place to be,’ he said, ‘and people let me be there.’21

During 1918, Archie recorded his daily activities in his Boy Scout’s notebook and diary, a four-by-three-inch leather-bound volume which was preserved by Cary Grant in his personal archive. A few typical entries from January of that year give one a good sense of how his free time had come to be dominated by the theatre:

14 Monday. After school I went and bought a new belt. And a new tie. Empire in evening. Daro-Lyric Kingston’s Rosebuds.

17 Thursday. Stayed home from school all day. Went to Empire in evening. Snowing.

18 Friday. My birthday. Stayed home from school. In afternoon went in town. In evening, Empire.

21 Monday. School. Wrote letter to Mary M. Empire in evening. Not a bad show. Captain De Villier’s wireless airship at the top of the bill.

22 Tuesday. School all day. In evening, Empire. All went well, first house. But second house, wireless balloon got out of control and went on people in circle. Good comedy cyclist called Lotto.22

He was nearing the age when he could leave school, and he was convinced that he wanted to work full-time in the theatre as soon as he possibly could. He was watching – and often meeting backstage – a broad range of music-hall acts, and he was eager to begin performing himself. At some unrecorded point during that period, probably late in 1917,23 he made contact with Bob Pender, who was the manager of a fairly well-known troupe of acrobatic dancers and stilt-walkers known as Bob Pender’s Knockabout Comedians.24 He had never achieved the kind of success enjoyed by Fred Karno, but he was an established and respected figure on the music-hall circuit.25 Archie had heard that the troupe was being depleted regularly as the younger performers reached military age: ‘When I found out that there were actually touring companies who would let you perform, and take you around the world, I was amazed, and it became my ambition to join one of these travelling shows.’26 In a letter on which he signed his father’s name, he wrote to Pender – who was on tour at the time – offering his services (but neglecting to note that he was not yet fourteen).27 Pender replied favourably, inviting Archie to report to Norwich as an apprentice.28

According to Cary Grant’s version of what happened, he intercepted Pender’s letter, ran away from home, caught the train to Norwich (paying the rail fare with money sent by Pender) and was placed in training with the troupe, practising cartwheels, handsprings, nip-ups and spot rolls.29 It took Elias more than a week to find him, eventually catching up with him in Ipswich, but whatever anger he had felt was swiftly assuaged by Pender, who was, Elias discovered, a fellow Mason.30 The two men agreed, over a drink, that Archie could return to the troupe as soon as he was allowed to leave school – an event that Grant later claimed he tried to hasten by getting himself expelled: doing his ‘unlevel best to flunk at everything’ and by cutting class after class.31

On 13 March 1918, for some undocumented reason, Archie Leach was suddenly expelled from Fairfield. In front of the school assembly, it was announced that he had been ‘inattentive … irresponsible and incorrigible … a discredit to the school’, and that he would be leaving immediately.32 There are at least four distinct versions of what had happened to precipitate such a radical measure. His own account, repeated and embellished in numerous interviews, was that he and another boy had been caught as they investigated the interior of the girls’ lavatories.33 A second, rather less racy, version, put forward by a classmate, claims that he was found in the girls’ playground: ‘His expulsion was so unfair. Several of us girls were in tears over it, because we didn’t like to lose him.’34 Another contemporary insists that the reason why he was expelled was that he had been ‘involved in an act of theft with two other boys in the same class in a town named Almondsbury, near Bristol’.35 Years later, G. H. Calvert, a headmaster of Fairfield, could not clarify the matter: ‘I have heard various accounts of the reason for his leaving the school, but have no reason to suppose that any one of them is truer than another. Probably only Mr Grant and the headmaster of the day knew the facts of the matter, and memories play tricks …’36 A fourth, and perhaps most plausible, theory is that the decision to expel Archie Leach was not inspired by some singularly dramatic misdemeanour but rather was the act of a broadly utilitarian headmaster (Mr Augustus ‘Gussie’ Smith) who had – along with the practically minded Elias Leach – reached the conclusion, after a string of petty incidents, that it would be best for all concerned if Archie Leach and Fairfield School parted company sooner rather than later.37

Three days later, Archie rejoined Bob Pender’s troupe. His father, on this occasion, made no attempt to restrain him, and ‘quietly accepted the inevitability of the news’.38 There was no legal hindrance to his re-employment. The contract between Bob Pender and Elias Leach, written in longhand, is preserved in Grant’s personal archive:

MEMORANDUM OF AGREEMENT

Made this day 9th Aug. 1918 between Robert Pender of 247 Brixton Road, London, on the one part, Elias Leach of 12 Campbell Street, Bristol, on the other part.

The said Robert Pender agrees to employ the son of the said Elias Leach Archie Leach in his troupe at a weekly salary of 10/- a week with board and lodging and everything found for the stage, and when not working full board and lodgings.

This salary to be increased as the said Archie Leach improves in his profession and he agrees to remain in the employment of Robert Pender till he is 18 years of age or a six months notice on either side.

Robert Pender undertaking to teach him dancing & other accomplishments needful for his work.

Archie Leach agrees to work to the best of his abilities.

Signed, BOB PENDER39

He began taking lessons in ground tumbling and stilt-walking and acrobatic dances. He practised using stage make-up. He studied the best ways to make full use of a wide range of stage props. He was also coached in the ways of ‘working’ an audience, of conveying a mood or a meaning without having recourse to words, establishing silent contact with an audience – a skill that he later acknowledged as having helped prepare him for the special challenge of screen acting.

Archie Leach had found a teacher he trusted. Bob Pender, a stocky, robust man in his early forties, was one of the most experienced and versatile physical comedians in England at that time. His real name was Lomas, the son and grandson of travelling players from Lancashire. His wife and co-director, Margaret, was former ballet mistress at the Folies Bergère in Paris. Archie, once he joined the troupe, lived with the Penders and the other young performers, either in their house in Brixton (the area long established, because of its close proximity to the forty-one London music-halls, as the home base of many professional entertainers40) or in boarding-houses on the tour circuit. It was an intense, practical and rapid education. Three months after he had left Bristol, Archie returned with the troupe to appear at the Empire. After the final curtain, Elias Leach, who had been in the audience, walked with his son back to his home. ‘We hardly spoke, but I felt so proud of his pleasure and so much pleasure in his pride, and I remember we held hands for part of that walk.’41 It was the closest that he had ever felt to his father.

The Pender troupe toured the English provinces and played the Gulliver chain of music-halls in London. The theatre became Archie Leach’s world, the source of his new identity; when he was not on stage, he was usually studying the other acts. ‘At each theatre I carefully watched the celebrated headline artists from the wings, and grew to respect the diligence it took to acquire such expert timing and unaffected confidence, the amount of effort that resulted in such effortlessness.’42 He became determined to learn how to achieve the illusion of effortless performance: ‘Perhaps by relaxing outwardly I thought I could eventually relax inwardly; sometimes I even began to enjoy myself on stage.’43

While on tour, the troupe was informed that it had been engaged for an appearance in New York. It was an extraordinary opportunity for all the young performers. There were twelve boys in the company, but provision for only eight in the contract that Pender had signed with Charles Dillingham, a New York theatrical impresario. Archie Leach – much to his relief – was one of the first of the troupe to be selected. On 21 July 1920, he joined the others on the RMS Olympic – sistership to the Titanic – and set sail for the United States of America.

CULTIVATION

Hughson: You’re a man of obvious good taste in, well, everything. How did you, I mean, why did you … Robie: You mean, why did I take up stealing? Oh, to live better. To own things I couldn’t afford. To acquire this good taste which younow enjoy. Hughson: You know, I thought you’d have some defense, some tale of hardship. Your mother ran off when you were young, your father beat you, or something. Robie: No, no. I was a member of an American trapeze act in the circus that travelled in Europe. It folded, and I was stranded, so I put my agility to a more rewarding purpose … TO CATCH A THIEF David: What do you want? Aunt: Well, who are you? David: Who are you? Aunt: Who are you? David: What do you want? Aunt: Well, who are you? David: I don’t know. I’m not quite myself today!BRINGING UP BABY