Полная версия

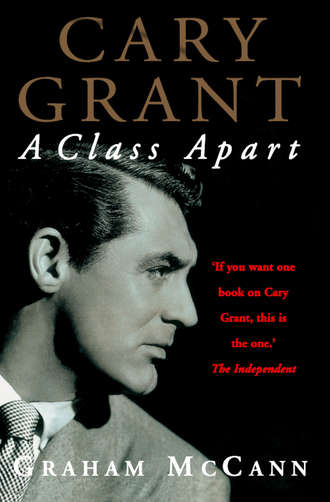

Cary Grant: A Class Apart

CARY GRANT

A Class Apart

Graham McCann

Copyright

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

This edition published in 1997

First published in Great Britain in 1996 by Fourth Estate

Copyright © 1996 by Graham McCann

The right of Graham McCann to be identified as the author of this

work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9781857025743

Ebook Edition © FEBRUARY 2016 ISBN: 9780007378722

Version: 2016-02-08

Dedication

For Silvanaand in memory of my dear grandparents,Frank and Florence Geary

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

PROLOGUE

BEGINNINGS

I Archie Leach

II A Mysterious Disappearance

III A Place to Be

CULTIVATION

IV New York

V Inventing Cary Grant

Hollywood

STARDOM

VII Never a Better Time

VIII The Intimate Stranger

IX Suspicions

INDEPENDENCE

X The Actor as Producer

XI The Pursuit of Happiness

XII The Last Romantic Hero

RETIREMENT

XIII The Real World

XIV The Discreet Celebrity

XV Old Cary Grant

Epilogue

Filmography

Keep Reading

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Notes

About the Publisher

Epigraph

Everybody wants to be Cary Grant.

Even I want to be Cary Grant.

CARY GRANT

Interviewer: Do you know the important people in the world today? Two hour old baby: Well, some. I don’t know, I’m not sure. Interviewer: You don’t know what you know? Two hour old baby: No. Interviewer: Do you know, for instance, Mickey Mantle? Two hour old baby: No. Interviewer: Queen Elizabeth? Two hour old baby: No. Interviewer: Winston Churchill? Two hour old baby: Ah, no. Interviewer: Fidel Castro? Two hour old baby: No. Interviewer: Pandit Nehru? Two hour old baby: No. Interviewer: Have you heard of Cary Grant? Two hour old baby: Oh, sure! Everybody knows Cary Grant!Carl Reiner and Mel Brooks, ‘The Two Hour Old Baby’

Prologue

A mask tells us more than a face.

OSCAR WILDE

Some might say they don’t believe in heaven

Go and tell it to the man who lives in hell.

NOEL GALLAGHER

Cary Grant was an excellent idea. He did not exist, so someone had to invent him. Someone called Archie Leach invented him. Archie Leach did not know who he was, but he knew what he liked. What he liked was what he came to think of as ‘Cary Grant’. He discovered that it was an extraordinarily popular conception. Everyone really liked the idea of Cary Grant. Archie Leach liked it so much that he devoted the rest of his life to its refinement.

It is easy to see why. Cary Grant was the man that most men dreamed of being, an exceptional man, the ‘man from dream city’.1 He was that most unexpected but attractive of contradictions: a democratic symbol of gentlemanly grace. No other man seemed so classless and self-assured, as happy with the world of music-hall as with the haut monde, as adept at polite restraint as at acrobatic pratfalls. No other man was equally at ease with the romantic and with the comic. No other man seemed sufficiently secure in himself and his abilities to toy with his own dignity without ever losing it. No other man aged so well and with such fine style. No other man, in short, played the part so well: Cary Grant made men seem like a good idea. As one of the women in his movies said to him: ‘Do you know what’s wrong with you? Nothing!’2

There was nothing wrong with Cary Grant. His colleagues admired him. ‘Cary’s the only actor I ever loved in my whole life,’ said Alfred Hitchcock.3 ‘If there were a question in a test paper that required me to fill in the name of an actor who showed the same grace and perfect timing in his acting that Fred Astaire showed in his dancing,’ said James Mason, ‘I should put Cary Grant.’4 To Eva Marie Saint, Grant was ‘the most handsome, witty and stylish leading man both on and off the screen.’5 James Stewart described him as a ‘consummate actor’,6 and Frank Sinatra remarked that ‘Cary has so much skill he makes it all look so easy’.7 Stanley Donen, the director, regarded him as ‘absolutely the best in the world at his job’:8 ‘If you asked almost any man in those days who would he like to be, you’d often get the answer “Cary Grant” – much more often than you would get the answer “the President of the United States”.’9

There was nothing wrong with Cary Grant. Movie audiences loved to watch him. In the era when movies were made with and around stars, the initial attraction being the name above the title, no fewer than twenty-eight Cary Grant movies – more than a third of all those he made – played at New York’s Radio City Music Hall (the largest, most important and prestigious movie theatre at that time in the United States) for a total of 113 weeks – a long-standing record.10 Again and again he was acknowledged as that theatre’s leading box-office attraction. One of his movies was the very first to earn $100,000 in a single week; another was the first to earn $100,000 in a single week at a single theatre. In the pre-eminent popular cultural medium of the twentieth century, Cary Grant was one of its most successful stars. His pulling-power stayed with him until the end of a movie career which lasted for over three decades; even in the year of his retirement, the Motion Picture Association of America voted him the leading box-office attraction.11 There was no decline, no fall from fashion. He was an exceptionally and enduringly popular star.12

There was nothing wrong with Cary Grant. Critics warmed to him. ‘We smile when we see him,’ wrote Pauline Kael, ‘we laugh before he does anything; it makes us happy just to look at him.’13 Richard Schickel suggested that ‘the only permissible response to him is bedazzlement’.14 In 1995, Premiere magazine lauded him as, ‘quite simply, the funniest actor the cinema has ever produced’.15 David Thomson judged him to be nothing less than ‘the best and most important actor in the history of the cinema’, in part because of his singular disposition, his ‘rare willingness to commit himself to the camera without fraud, disguise, or exaggeration, to take part in a fantasy without being deceived by it’,16 and in part because of the extraordinary richness of the results of this commitment, an art mature and elaborate enough to embrace the ambiguities of a self shown in close-up.

There was nothing wrong with Cary Grant. There was much, however, that was extraordinary about him. That accent: neither West Country nor West Coast, neither English nor American, neither common nor cultured, strangely familiar yet intriguingly exotic (as someone in Some Like It Hot exclaims: ‘Nobody talks like that!’). That expression: capable of blending light and dark inside a single look, hinting at much more than it holds up for show. That walk: confident, athletic and slightly rubber-legged, fit for slapstick as well as for sophistication. He was, in an unshowy way, unusually versatile: he could play submissive, naive, child-like characters (such as in Bringing Up Baby) or worldly-wise charmers (as in Suspicion) or world-weary cynics (as in Notorious). John F. Kennedy thought that Grant would be his ideal screen alter ego, but then so did Lucky Luciano;17 Grant’s exceptionally broad appeal was in part to do with his bright roundedness, the promise of completion, showing the coarse how to have class and the over-refined how to have the common touch, teaching the unruly how to behave and the repressed how to have fun. What was so remarkable was how Cary Grant himself seemed to be so conspicuously complete. No one else was quite like him. There was something odd, something peculiar even, about his perfection.

‘Everybody wants to be Cary Grant,’ said Cary Grant. ‘Even I want to be Cary Grant.’18 It was not meant as a boast, but rather as an admission of vulnerability. Cary Grant appreciated – more so than anyone else – how difficult it was to be ‘Cary Grant’, because he knew that he was far from perfect. ‘How can anyone’, asked David Thomson, ‘be “Cary Grant”? But how can anyone, ever after, not consider the attempt?’19 It is really not so strange that even Cary Grant could not always succeed in being ‘Cary Grant’. It is not as if Archie Leach had always found it easy to be Archie Leach. The difference is that everyone knows who ‘Cary Grant’ is supposed to be, everyone knows the rules, while not even Archie Leach was ever very sure of who Archie Leach was supposed to be.

Everybody knows Cary Grant. What everybody knows about Cary Grant, however, is largely what he wanted us to know. Leslie Caron, one of his last co-stars, recalled: ‘He would say, “Let the public and the press know nothing but your public self. A star is best left mysterious. Just show your work on film and let the publicity people do the rest.”’20 He lived much of his life on the screen, in the movies, making us believe in Cary Grant, showing his image at each stage in its slow and subtle evolution. When he retired, he withdrew from view. There were no opportunities for disenchantment: no kiss-and-tell memoirs, no television specials, no embarrassing scenes, no political pronouncements, no diet books or diaries, no talk-show appearances, no authorised biographies, no comebacks, no second thoughts. He never told us how he had managed to be Cary Grant so well for so long. He cared too much, or too little, to let on; he liked to keep us guessing. To accept definition was to invite disqualification. He was content, it seemed, just to live with – or behind – the mystery. The mystery had, after all, served him very well. Why let in daylight upon magic?21 ‘Besides,’ he said, with a playful insouciance, ‘I don’t think anybody else really gives a damn.’22

Cary Grant was an excellent idea. The last person who wanted to deconstruct that idea was Cary Grant:

Who tells the truth about themselves anyway? A memoir implies selectiveness, writing about just what you want to write about, and nothing else. To write an autobiography, you’ve got to expose other people. I hope to get out of this world as gracefully as possible without embarrassing anyone.23

It was typically Cary Grant: polite, urbane, decent and discreet – and very much in control. He looked on with wry amusement as the old tales were retold and the new myths manufactured: he ignored all the parodies and pretenders, all the old quotations and well-worn misconceptions, all the ‘Judy, Judy, Judys’ and the ‘How old Cary Grants’. He did not rise to the bait. He refused to involve himself in the investigations. He kept his self for himself. ‘Go ahead, I give you permission to misquote me,’ he told his uninvited chroniclers. ‘I improve in misquotation.’24

Cary Grant, in more than one sense, was a class apart. Socially, he was a glorious enigma, eluding every pat classification. Artistically, he was, in his own particular field, without peers. In a leading article in the Washington Post shortly after his death, it was said that the name ‘Cary Grant’, ‘in the absence of anyone remotely like him on the screen, continued to be a synonym for a set of qualities his friends and admirers inevitably summed up as “class”’.25 Cary Grant did indeed have class. He was a master of the ‘high definition performance’, a term defined by Kenneth Tynan as ‘the hypnotic saving grace of high and low art alike’, characterised by ‘supreme professional polish, hard-edged technical skill, the effortless precision without which no artistic enterprise – however strongly we may sympathise with its aims or ideas – can inscribe itself on our memory’.26

Everybody wanted to be Cary Grant. Everyone else, before and since, failed. It took someone special to succeed. It took Archie Leach.

BEGINNINGS

It is not dreams of liberated grandchildren which stir men andwomen to revolt, but memories of enslaved ancestors.

WALTER BENJAMIN

Peace. That’s what I’m looking for. I want peace. Withhappy hearts and straight bones without dirt and distress.

Surprises you, don’t it? Peace – that’s what us millions want,without having to snatch it from the smaller dogs. Peace – tobe not a hound and not a hare. But peace – with pride tohave a decent human life, with all the trimmings.

NONE BUT THE LONELY HEART

CHAPTER I Archie Leach

Don’t I sound a bounder!

CARY GRANT

Take it from me: it don’t do to step out of your class.

JIMMY MONKLEY

Cary Grant was a working-class invention. His romantic elegance, as Pauline Kael remarked, was ‘wrapped around the resilient, tough core of a mutt’.1 It is one of the greatest and most mischievous cultural ironies of the twentieth century that the man who taught the privileged élite how a modern gentleman should look and behave was himself of working-class origin. It took Archie Leach – poor Archie Leach – to show the great and the good how to live with style. It was Archie Leach, born into such inauspicious circumstances, who became the man others liked to be seen with, a role model for the socially ambitious, the well bred and even the royal. ‘When you look at him’, said Kael, ‘you take for granted expensive tailors, international travel, and the best that life has to offer.’2 Cary Grant exuded urbane good taste and inoffensive prosperity: ‘There were no Cary Grants in the sticks’; Grant represented the most distinguished example of ‘the man of the big city, triumphantly suntanned’.3

The transformation of Archie Leach into Cary Grant was contemporaneous with, but different from, that of James Gatz into Jay Gatsby. The mysterious and glamorous figure in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby ‘sprang from his Platonic conception of himself’,4 suddenly, out of sight, without explanation. Cary Grant, on the other hand, took time to take over Archie Leach. Both Leach and Gatz came from poor backgrounds, their parents ‘shiftless and unsuccessful’;5 both longed to grow, to change, to escape (Leach from Bristol, Gatz from West Egg, Long Island) and reinvent themselves as the kind of attractive, successful, stylish young man of wealth and taste ‘that a seventeen-year-old boy would be likely to invent’;6 and both possessed an extraordinary ‘gift for hope’,7 a quality commented on by another character in the novel:

If personality is an unbroken series of successful gestures, then there was something gorgeous about him, some heightened sensitivity to the promises of life, as if he were related to one of those intricate machines that register earthquakes ten thousand miles away.8

The two men differed, however, in their relationship with their old identities; Gatsby was a tense denial of Gatz whereas Grant was a warm affirmation of Leach. With Gatsby, all the careful gestures – the pink suits, the silver shirts, the gold ties, the Rolls-Royce swollen with chrome, the pretensions to an Oxford education, the clipped speech, the ‘old sports’, the formal intensity of manner – helped to conceal the unwelcome persistence of the insecure ‘roughneck’, James Gatz. With Grant, however, the accent, the mannerisms, the values, the sense of humour, continued to underline the strangeness of his cultivation. To Gatsby, any memory of Gatz, any recognition of the prosaic facts of his existence, represented a threat to his new identity. To Grant, on the contrary, Archie Leach remained with him, an intrinsic part of his life and character, an affectionate point of reference in his movies and his interviews: Archie Leach was no threat to his – or others’ – sense of himself. Archie Leach was the measure of his success and, in a profound sense, a reason for it.

Cary Grant’s life was lived in the midst of a vibrant American modernity, but Archie Leach’s English childhood was solidly Edwardian. Queen Victoria had died just three years before he was born, and he grew up in a world of gas-lit streets, horse-drawn carriages, trams and four-masted schooners. The culture of the time discouraged – and sometimes mocked – thoughts of upward social mobility. E. M. Forster’s Howards End (1910), for example, depicted the petit bourgeois Leonard Bast as limited fundamentally by his undistinguished background: he was ‘not as courteous as the average rich man, nor as intelligent, nor as healthy, nor as lovable’;9 he has a ‘cramped little mind’,10 plays the piano ‘badly and vulgarly’11 and is married to a woman who is ‘bestially stupid’;12 his hopeless pursuit of culture is curtailed when he dies of a heart attack after having a bookcase fall on top of him. This was the England of Archie Leach. In this England the story of Cary Grant would have seemed incomprehensible.

Archibald Alexander Leach13 was born on Sunday, 18 January 1904, at 15 Hughenden Road, Horfield, in Bristol. Elias James Leach, his father, was a tailor’s presser by trade, working at Todd’s Clothing Factory near Portland Square. He was a tall, good-looking man with a ‘fancy’ moustache, soft-voiced but convivial by nature and at his happiest at the centre of light-hearted social occasions. Elsie Maria Kingdon Leach,14 his mother, was a short, slight woman with olive skin, sharp brown eyes and a slightly cleft chin; she came from a large family of brewery labourers, laundresses and ships’ carpenters. She had married Elias in the local parish church on 30 May 1898. Some of Elsie’s friends felt that Elias was rather irresponsible and, worse still, ‘common’, more obviously resigned than she to their humble position; but it seems that she was, at least for the first few years of their relationship, genuinely in love with him. The family lived at first in a rented two-storey terraced house situated on one of the side streets off the main Gloucester Road leading out of Bristol. Built of stone and heated solely by relatively ineffectual coal fires in small fireplaces, the house was bitterly cold in winter and chillingly damp the rest of the time.

Archie Leach was born in the early hours of one of the coldest mornings of the year. Like most babies at that time, he was delivered at home in his parents’ bedroom. The uncomplicated birth, and the baby’s subsequent good health, were greeted with particular relief by the couple. Their first child, John, had died four years earlier – just two days short of his first birthday – in the violent convulsions of tubercular meningitis.15 Elsie had sat beside his cot night and day until she was exhausted; the doctor had ordered her to sleep for a few hours, and, as she slept, the baby died.16 The loss had left Elsie – who was only twenty-two at the time – seriously depressed and withdrawn, and Elias, living in the city that was the centre of the wine trade, had taken to drink. The marriage was put under considerable strain. Eventually, the family doctor advised the couple to try for another child to compensate for their loss. They did so. Archie was to be, in effect, their only child.

It is at this very early stage that one encounters the first of several points of contention in Grant’s biography. Archie Leach was circumcised,17 which was a fact that later encouraged some biographers to identify him as Jewish.18 It is not, however, as simple as that. Pauline Kael, among others, has suggested that Elias Leach ‘came, probably, from a Jewish background’,19 and it has been said by some that Cary Grant himself believed that the reason for the circumcision must have been due to his father being partly Jewish, but, curiously, there is no record of any Jewish ancestors in Elias’s family tree, nor is there any solid evidence to suggest that he thought of himself as Jewish. We do know that Elias and Elsie attended the local Episcopalian Church every Sunday. Circumcision was not, however, it has to be said, a common practice outside the Jewish community in England at that time;20 it is possible, of course, that the Leaches were advised that it was – in Archie’s case – an action that was necessary or prudent for particular medical reasons (and, after the death of their first child, they would surely have taken any such advice extremely seriously), but, again, there is nothing recorded which could clarify the matter.