Полная версия

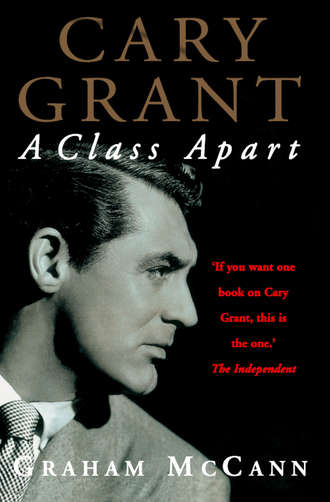

Cary Grant: A Class Apart

If the accent was, and would continue to be, unique, it was distinctive in the ‘right’ kind of way as far as Hollywood producers were concerned. There was a demand at the time for British (or at least British-sounding) actors, because the diction of so many American performers was, it was thought, ill-suited to the technical limitations of the early ‘talkies’. Although Archie Leach had arrived in Hollywood with his accent a volatile mixture of West Country, South London and New York, Cary Grant was able to attract attention by the way he sounded as well as by the way he looked. That accent, as a critic, Alexander Walker, has pointed out, gave the new personality an ‘edge’; it impressed on the voice ‘the sharpness that comedy needs if it’s to be slightly menacing’.41 It would, in time, become the kind of accent that could underline the humour in well-written dialogue and disguise the absence of it in the most mediocre of lines. Writers, as a consequence, were among Cary Grant’s most genuine admirers. Listen to the way, in The Awful Truth (1937), that Grant, serving a rival with a glass of egg-nog, manages to make the innocent question, ‘A little nutmeg?’ sound like a threat, or how, in The Grass is Greener (1960), he places such an artfully sardonic emphasis on the question, ‘Do you like Dundee cake?’, that it succeeds in mocking both the place-name and the antiquated mannerisms of his upper-class character. Cary Grant would become the kind of person who, as David Thomson put it, ‘could handle quick, complex, witty dialogue in the way of someone who enjoyed language as much as Cole Porter or Dorothy Parker’, with a memorably serviceable accent, caught between English and American, working-class and upper-class, that produced a tone that could be made to sound ‘uncertain whether to stay cool or let nerviness show’.42

If Cary Grant was going to be someone who sounded unorthodox, he was also, in rather less obvious but equally significant ways, going to be someone who looked unorthodox. Whereas most other actors in Hollywood at that time were known either for their physical or verbal skills, Archie Leach, unusually, possessed both. Silent screen comedy had demanded performers who could be as funny as possible physically, noted the critic James Agee, ‘without the help or hindrance of words’. The screen comedian, before sound took hold of Hollywood, ‘combined several of the more difficult accomplishments of the acrobat, the dancer, the clown and the mime’.43 The advent of the ‘talkies’ marked a change in direction. Archie Leach, with his vocal mannerisms and his acrobatic training, had the rare opportunity to make Cary Grant an appealing hybrid: a talented physical performer with a rare gift for speaking dialogue, someone who could, whilst remaining in character, utter a string of sophisticated witticisms before slipping suddenly on a solitary stuffed olive and landing ignominiously on his backside. One movie historian commented on what it was like to grow up in the 1920s with but one wish: to be ‘as lithe as Fairbanks and as suavely persuasive as Ronald Colman’.44 Cary Grant had the rare chance to realise such a wish.

Archie Leach did not take long to see that the opportunity existed, and Cary Grant exploited it. He brought athleticism to elegance, physical humour to the drawing-room. It was the kind of unexpected versatility which undermined the rigid screen stereotypes, and it would help Cary Grant to become ‘an idol for all social classes’.45 As Kael explains, other leading men, such as Melvyn Douglas, Henry Fonda and Robert Young, could produce proficient performances in screwball comedies and farcical situations, ‘but the roles didn’t release anything in their own natures – didn’t liberate and complete them, the way farce completed Grant’.46 It was as though the grace of Fred Astaire had combined with the earthiness of Gene Kelly. David Thomson observed: ‘Only Fred Astaire ever moved as well as Cary Grant, but Grant moved with more dramatic eloquence while Astaire cherished the purity of movement. Grant could look as elegant as Astaire, but he could manage to look clumsy without actually sacrificing balance or style.’47

Cary Grant’s potential could not be realised, however, until Archie Leach found the confidence to start acting like Cary Grant, and to start he needed first to develop a reasonably sharp sense of who Cary Grant should act like. Cary Grant, Archie Leach decided, should act like those stars who, up until then, had most impressed him. By his own admission, Cary Grant was in part, at the beginning, patterned on a combination of elegant contemporary Englishmen:

In the late 1920s I’d wavered between imitating two older English actors, of the natural, relaxed school, Sir Gerald DuMaurier and A. E. Matthews, and was seriously considering being Jack Buchanan and Ronald Squire as well; but Noël Coward’s performance in Private Lives narrowed the field, and many a musical-comedy road company was afflicted with my breezy new gestures and puzzling accent.48

Coward’s unapologetically reinvented self – and accent – was of particular relevance. Alexander Walker comments how Coward’s example – above all others – probably encouraged Archie Leach ‘to abandon the stigmata of English class’.49 Archie Leach had admired another British playwright, Freddie Lonsdale, because he ‘always had an engaging answer for everything’,50 but Coward’s supremely confident manner and sparkling wit, as well as his success on both sides of the Atlantic (The Vortex had broken box-office records on Broadway), were particularly influential. Leach’s imitation, fixed as it was on the surface aspects of self, was graceless at first, but he learned from its limitations: ‘I cultivated raising one eyebrow, and tried to imitate those who put their hands in their pockets with a certain amount of ease and nonchalance. But at times, when I put my hand in my trouser pocket with what I imagined was great elegance, I couldn’t get the blinking thing out again because it dripped from nervous perspiration!’51

In addition to the English role-models, Archie Leach also looked to those examples he had noted of American charm and elegance. Fairbanks was, of course, an important influence, but so too were Fred Astaire and the man described by Philip Larkin as ‘all that ever went with evening dress’,52 Cole Porter (whom Cary Grant later portrayed – much to his discomfort and Porter’s delight – in the 1946 musical Night and Day). Another significant figure for Archie Leach was the actor Warner Baxter, described by one journalist at the time as ‘a Valentino without a horse’,53 the ‘beau ideal’ who had been the first screen incarnation of Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1926) as well as the leading man in the first version of The Awful Truth (1925) – the re-make of which confirmed Cary Grant as a star.

A Hollywood star persona was cultivated, typically, through a combination of performance – carefully-chosen screen roles – and publicity – studio press releases and magazine stories.54 Cary Grant emerged at a time when audiences had started reading rather more than before about the performers they saw on the screen; the fan magazine detailed every aspect of the stars’ lives, real and imaginary, and they sold by the million:

The success of the fan magazine phenomenon of the 1930s was a co-operative venture between the myth makers and an army of readers willing to be mythified. The magazines rewarded their true believers with a Parnassus of celluloid deities who climbed out of an instant seashell like Botticelli’s Aphrodite.55

Motion picture magazines soon began referring to Paramount’s ‘suave, distinguished’ Cary Grant, a new star-in-the-making for whom, it was said, ‘the word “polished” fits … as closely as one of his own well-fitting gloves’.56 He was, readers were told, a ‘handsome’ and ‘virile’ young man who ‘blushed “fiery red” when embarrassed’, and, it was added, he had the ‘same dreamy, flashy eyes as Valentino’.57 While his studio worked hard to find the right kind of publicity to promote its own version of ‘Cary Grant’, he was advised, in the short term, to say little of any consequence himself. However, the studio soon realised that Grant was actually being rather too reticent for his own good. A Paramount publicist at the time came to regard the task of securing coverage for the relatively unknown Cary Grant as probably the most difficult and frustrating experience of her whole career as a press agent.58 Having grown up with very few close personal ties, he had developed the habit of keeping his thoughts and beliefs to himself, and, having recently transformed his public self, he was over-cautious when subjected to journalistic requests for all the ‘facts’ about Cary Grant rather than Archie Leach. As one reporter noted after a very early encounter with him, ‘Anything he says about himself is so offhand and perfunctory that from his own testimony you get only the sketchiest impression of him.’59 A writer on Motion Picture magazine was similarly frustrated: ‘Seldom have I seen a man so little inclined to pour out his soul, and you have to scratch around and dig in order to discover even the bare facts of his life from him.’60

Paramount could package Cary Grant but it could not control entirely how he impressed himself on a movie audience. If Cary Grant was in danger of resembling a tabula rasa in the journalistic profile, on the movie screen he would soon seem, as Katharine Hepburn put it, ‘a personality functioning’.61 On the screen Cary Grant could be himself rather than explain himself (and that alone, in a sense, provided one with an adequate explanation). The actor Louis Jourdan has spoken of the impact that Cary Grant’s early movie performances had on him: ‘I was in awe of this persona, the look, the walk … The Cary Grant I fell in love with on the screen hadn’t yet discovered he was Cary Grant.’62 This new, unfamiliar, intriguing character called ‘Cary Grant’ was, as Jourdan appreciated, someone who did not fit neatly into the stereotypical roles but who was, on the contrary, a character in conflict with himself:

Behind the construction of his character is his working-class background. That’s what makes him interesting. That’s what makes him liked by the public. He’s close to them. He’s not an aristocrat. He’s not a bourgeois. He’s a man of his people. He is a man of the street pretending to be Cary Grant!63

It was one of the most admirable achievements of Cary Grant: that he never had, or wished, to renounce his past in order to embrace his future. Unlike those stars who seemed ashamed of, or embarrassed by, their humble origins, Cary Grant seemed content to stand upon his singularity; it would, for example, have taken a reckless person to risk calling Rex Harrison ‘Reg’ to his face, but Cary Grant delighted in slipping references to his former name into his movie dialogue – such as the ad-libbed line in His Girl Friday (1940): ‘Listen, the last man who said that to me was Archie Leach just a week before he cut his throat.’64 It was a knowing wink to the audience, his audience, a secret shared with strangers; it was the kind of gesture that would have endeared someone like Cary Grant to someone like Archie Leach.

Archie Leach did not cease to exist when Cary Grant was created. ‘Cary Grant’ was just a name, a cluster of idealised qualities. Cary Grant became something other than the sum of his influences, and he preserved more than it might have appeared from his own personal history in that charismatic conformation. Cary Grant was not conceived of as the contradiction of Archie Leach, but rather as the constitution of his desires. If Cary Grant succeeded, Archie Leach, more than anyone else, more than any other influence or ingredient, would be responsible. Cary Grant would always appreciate that fact. Fifty years after he changed his name, when he was the subject of a special tribute,65 he requested that the cover of the programme for the occasion should feature a photograph of himself at the age of five – signed by ‘Archie Leach’.

CHAPTER VI Hollywood

Since I was tall, had black hair and white teeth, which I polished daily,I had all the semblance of what in those days was considered a leadingman. I played in the kind of film where one was always polite andperfectly attired.

CARY GRANT

You must not forget who you are …

FEDORA

It was an anxious Cary Grant who reported to work for the first time at Paramount. Archie Leach had a new name, but he had yet to make a new reputation. Here he was at the studio of Marlene Dietrich, Gary Cooper, Maurice Chevalier, Fredric March, the Marx Brothers, W. C. Fields, Claudette Colbert, Tallulah Bankhead, Miriam Hopkins, Sylvia Sidney, Carole Lombard and Harold Lloyd – big stars, experienced performers. The only person with whom Archie Leach was acquainted was Jeanette MacDonald, but her option had not been renewed and she was leaving the studio. Cary Grant was on his own.

If Cary Grant was intimidated by his new surroundings, he was not disheartened. Jean Dalrymple, who had given Archie Leach his first paid speaking role in vaudeville, recalled:

I had lunch with him at the Algonquin just before he went to California. He was so excited. He felt it was his great opportunity. I remember telling him not to get stuck in California but to come back to the theater from time to time.

I didn’t know he was going to be a sensational hit. He didn’t always have that marvelous, debonair personality. He was often very quiet and reserved. But when he got in front of a camera, his eyes sparkled and he was full of life. The camera loved him.1

Cary Grant’s Hollywood was the Hollywood of the thirties. The effects of the Wall Street Crash were still being felt, and yet memories of the event, which had hit movie-makers in the West as well as more conventional businessmen in the East, were already – for some – receding. Audiences were still visiting America’s vast rococo and Moorish picture palaces, those strangely aristocratic arenas of the new democratic art where visitors were greeted with an anxious show of opulence – fountains and waterfalls, painted peacocks and doves, huge mirrors and grand arcades, thick carpeting and air-conditioning, all designed to project, for a few hours, an illusion of prosperity. If it seemed to the weary, depression-ridden citizen that the American dream could not be lived, then Hollywood studios worked hard to remind people that it could still be imagined. ‘There’s a Paramount Picture probably around the corner’, the studio told Saturday Evening Post readers. ‘See it and you’ll be out of yourself, living someone else’s life … You’ll find a new viewpoint. And tomorrow you’ll work … not merely worry.’2 It was a relatively successful strategy. In the midst of the Great Depression, audiences were still exhibiting what in the circumstances appeared a remarkable appetite for the products of Hollywood. In the first half of the decade, however, Paramount, ruled by Adolph Zukor, lacked the rock-like business stability of, for example, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, and the profit or loss incurred by one movie tended to affect unduly the studio’s financial climate.3 In the year that Cary Grant joined the studio, Paramount had made a sixteen-million-dollar loss, with possible bankruptcy ensuing.

Paramount – not surprisingly – had no intention of starting Cary Grant in important leading roles, but he would have more than enough opportunities to attract the attention of movie audiences. The company (after a policy of wild and rashly overoptimistic expansion during the second half of the 1920s) owned the largest circuit of theatres in the world, which it kept supplied by producing around sixty feature films per year. Operating on increasingly strict factory lines, it completed and shipped at least one new movie every week, so there was always a place for a new contractee somewhere along the assembly line. As a newcomer, Cary Grant was expected to work extremely hard for his $450 a week. He was there, without doubt, to do what he was told. It was a six-day schedule, Monday to Saturday, with no extra pay for overtime (which was common). The bare statistics of his first year with the studio reflect the production-line smoothness of the times: he made seven movies in 1932, working a full fifty-two weeks.

During Grant’s first few hectic weeks at the studio he found a supporter in Jack Haley, the comedian, who later achieved his greatest Hollywood success in the role of the Tin Man in The Wizard of Oz (1939). As his son, Jack Haley, Jnr., remembers, Grant was grateful to know someone else who had made the transition from vaudeville to movies:

When Cary was first at Paramount, he made a bee-line for my father, who had already done six or seven pictures there … Cary wanted to know what making movies was all about. My father told him, ‘The first thing you learn is not to use your stage makeup. So find a good makeup person. And don’t talk to the leading actress. She’ll steer you wrong. She’s your competition. Talk to the character people. They’ll teach you the ins and outs.’

Cary loved Charlie Ruggles, Arthur Treacher, and all those character people who came from Broadway or vaudeville. He felt secure with them. Years later Cary told me, ‘Your father was the only one who gave me advice for my first picture’.4

Grant first appeared, billed fifth, in Frank Tuttle’s farce This is the Night. Playing the supporting role of an Olympic javelin thrower whose wife is having an affair with a millionaire playboy, Grant was described in the advertisements for the movie as ‘the new he-man sensation of Cinemerica!’5 Tuttle left Grant largely to his own devices, which were still those of a stage-trained actor, and, as a consequence, his performance showed no appreciation of the importance of underplaying. At eighth in the cast list, he was less noticeable as a rich roué in Alexander Hall’s Sinners in the Sun, his first of two disappointing movies with Carole Lombard, although he did have his first chance to show audiences how good he looked in evening clothes. Equally facetious, and even more devoid of opportunities for Grant to impress, was Dorothy Arzner’s Merrily we go to Hell, in which his contribution, billed ninth, was always going to be negligible. A slightly more promising role was then given to him by Marion Gering in The Devil and the Deep, the stars of which were Tallulah Bankhead, Charles Laughton and Gary Cooper.6

Of the three other movies in which Grant appeared in 1932 – Blonde Venus, Hot Saturday and Madame Butterfly – by far the most significant was Josef von Sternberg’s Blonde Venus starring Marlene Dietrich. It was the first good, substantial, role he had been given, one that would provide him with a serious opportunity to show that he could convince audiences as a romantic consort. He was playing opposite the nearest thing that Paramount had at that time to a screen ‘goddess’, and she was treated accordingly; her custom-built four-room dressing-suite had cost the studio $300,000 (about sixty times the cost of an average US family dwelling in 1932), she had the right to veto her publicity and, with von Sternberg as her director and mentor, an unusually influential say in the selection, and production, of her starring vehicles.

It was while making this, his fifth, movie, and the first that Gary Cooper had rejected, that Grant’s image underwent a minor but significant cosmetic transformation. The director, von Sternberg, ever the meticulous auteur, changed Grant’s hair parting from the left to the right. According to Alexander Walker, the main reason why von Sternberg decided to change the parting was to annoy and unsettle Grant.7 ‘Joe loved to throw you,’ Grant told Walker. ‘Could you do anything worse to an actor than alter his hair parting just a minute before he starts shooting a scene? I kept it that way ever since, as you may have noticed. To annoy him.’8 It also, as he (and von Sternberg) probably knew, improved his appearance; his ‘best side’, for the camera, was his right (he disliked the mole on his left side), and the new ramrod-straight parting (which became the single most simple and straightforward thing about him) complemented his other features.

The inexperienced and under-confident Grant did not enjoy working for von Sternberg. There were periods when he was left to look on bemused as the director and the star argued with each other in German, and there were other times when the director seemed intent on turning his fury onto him: ‘I could never get a scene under way before Joe would bawl out “Cut” – at me, personally, across the set. This went on and on and on. I felt like someone doing drill who kept dropping his rifle, but wasn’t going to be allowed to drop out of ranks.’9 Grant was miscast as Nick Townsend, a politician (‘he runs this end of town’) who makes Dietrich his mistress, enabling her to pay for her ailing husband, played by Herbert Marshall, to travel to Germany in search of a cure for his illness. Marshall – who, as Richard Schickel has rather cruelly remarked, ‘always played civility as if it were a form of victimisation’10 – should have provided Grant with a useful contrast for his own characterisation; von Sternberg, however, allowed Grant to throw away even his passionate speeches, and for too much of the movie he appears so self-effacing as to be almost invisible. He was, however, beautifully lit and photographed – as were all the leading actors – and he looked good in his fine clothes and glamorous environment. It was, in short, a helpful movie for an ambitious young actor, even if von Sternberg left him feeling, if anything, even less confident than before.

Amidst the unfamiliarity of his new surroundings, Cary Grant, like countless other new arrivals with British backgrounds, sought and found, at least for a short while, a relatively reassuring sense of security and stability in that tightly-knit community of émigré English actors and writers sometimes referred to as the ‘Hollywood Raj’ or the ‘British movie colony’.11 A few English performers, such as Charlie Chaplin and Stan Laurel, had arrived as early as 1910 as refugees from Victorian music-hall, but the coming of sound had been the signal for a further wave of stage-trained English actors. Though the British mixed fairly freely with the rest of Hollywood society, they seemed, in spite of it, to retain a certain separateness. In the mid-thirties, the Christian Science Monitor, reporting on foreigners in Hollywood, was particularly struck by the obduracy of the British in their preservation of their culture:

Several English cake shops now exist, catering almost exclusively to the English, who maintain a stricter aloofness than do most other resident aliens; steak and kidney pies have miraculously made their appearance all over town and are sometimes even eaten by the natives; Devonshire cream is also manufactured, but in very small quantities … Once a year, on New Year’s Eve, the principal members of the British colony gather in a Hollywood café to hear the bells of Big Ben ring out over the radio … Billiards are now played regularly at the homes of most British stars, and officers of the British warships visiting in California harbors entertain and are entertained by a group founded by Victor McLaglen and known as the British United Services Club, comprised in large part of actors who have served in one of the branches of the British military; while on many a film set old members of the same London club [usually the Garrick], meet and fraternise.12

Many of these English actors had found work in Hollywood because of their ‘exotic’ qualities – their looks, their mannerisms and their accents. Their relative insularity, therefore, was not merely the result of homesickness or cultural taste but also, in many cases, professional necessity; to mix too freely and too frequently with one’s American colleagues was to risk becoming fully assimilated by, and acculturated in, American society. The commercial appeal of many English actors was their Englishness; English actors who looked and sounded American, unless they were remarkably talented, faced much fiercer competition for roles. Many of the most successful English actors of the time were well aware of the danger. Ronald Colman, Artur Rubinstein recalled, possessed a ‘beautiful’ English accent which actually ‘became better and more marked with time instead of becoming Americanised’,13 while C. Aubrey Smith, specialising in playing a limited range of crusty English colonel types, developed and preserved a lucrative cluster of echt-English mannerisms for the enchantment of American audiences. There were some for whom the need, or desire, to maintain their cultural distinctiveness caused them, gradually but usually inexorably, to settle into a comfortable form of self-parody. Aubrey Smith – who once summed up his experience of working with Garbo in Queen Christina in the remark, ‘She’s a ripping gel’,14 and who lived in a house on Mulholland Drive that boasted a weather vane made out of three cricket stumps, a bat and a ball – was a comically anachronistic figure even for most of his compatriots, while Gladys Cooper, taking tea one warm afternoon at the Pacific Palisades home of Robert Coote, reacted with typical mock-horror to the arrival of George Cukor by exclaiming disapprovingly: ‘Darling … there seems to be an American on your lawn.’15